Key Points

- Most young people referred to school-based mental health support were girls and teenagers.

- Teenagers and girls reported higher anxiety and depression than younger children and boys.

- Parents often rated children’s difficulties as more severe than the children did themselves.

- School-based services accepted more referrals than traditional NHS pathways, suggesting better access to early help.

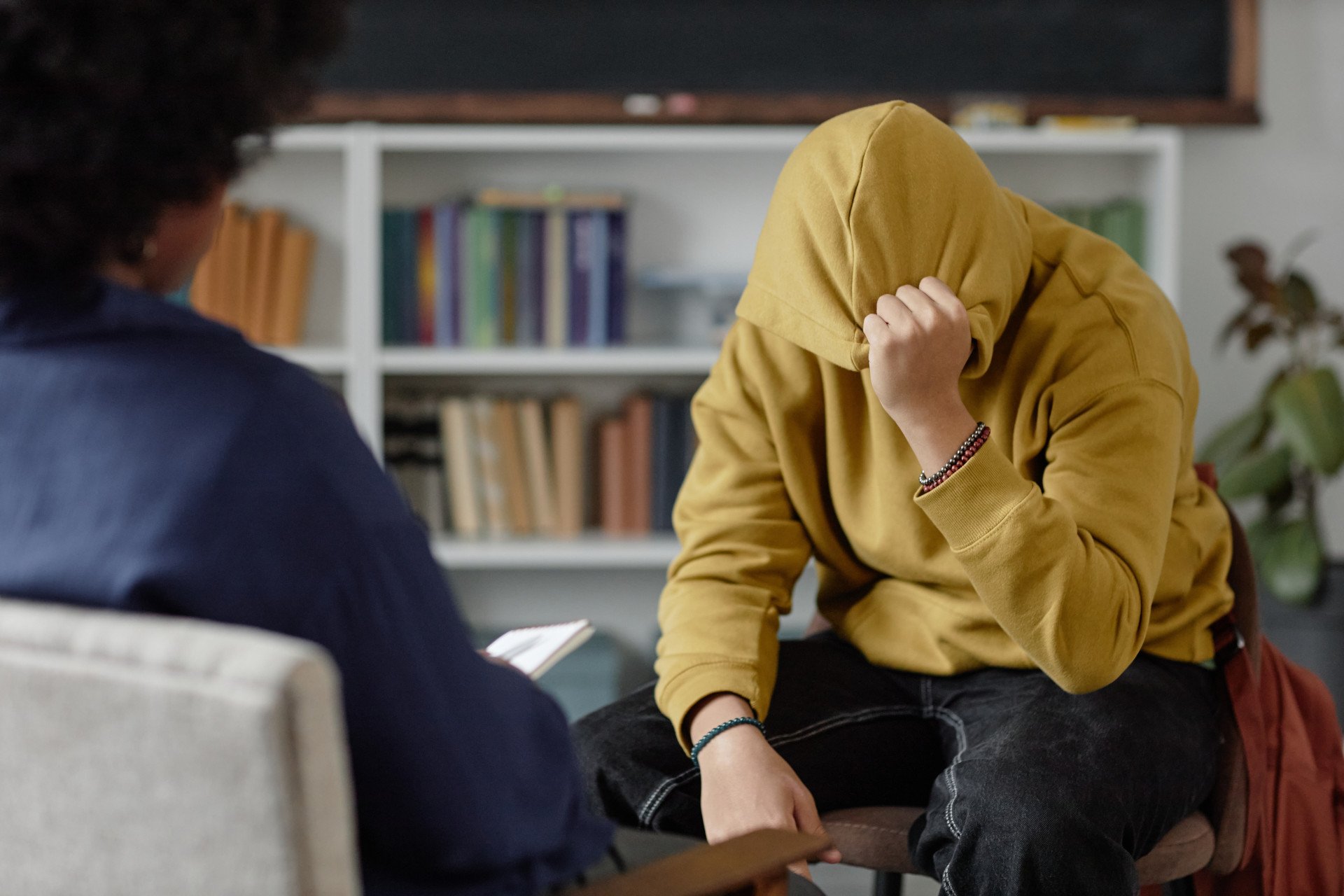

The morning classroom mask

Imagine a 14-year-old walking into school, head down, hoodie up, earbuds in.

To classmates and teachers, they look “fine” – just another quiet teenager.

But inside, their thoughts race, heart pounds, and an invisible heaviness drags at every step.

Now picture a parent at home, filling out forms for support, convinced their child’s struggles are spiraling faster than anyone else can see.

Which story is true – the young person’s or the parent’s?

A new UK study suggests both matter, and often, they don’t match.

Why schools stepped in

Traditional mental health services for children and adolescents – known as CAMHS – have long waiting lists and strict thresholds.

Many young people with “mild to moderate” difficulties slip through the cracks.

In response, the UK government introduced Mental Health Support Teams (MHSTs) in schools.

Staffed by Educational Mental Health Practitioners trained in cognitive-behavioural approaches, these teams focus on early, low-intensity support for issues like anxiety, low mood, sleep, and behaviour.

The study looked at every child referred to two MHST sites in West Sussex in 2021 -right after the turbulence of the pandemic.

By analysing both demographics and symptom reports, researchers wanted to know:

who makes it through the door, what difficulties they bring, and how their stories differ depending on whether you ask the child or the parent.

Who sought help?

Across 485 referrals, three patterns stood out.

Most were secondary school pupils (57%), most were girls (61%), and most were White British (81%), reflecting the local population.

Interestingly, boys made up almost half of primary school referrals but dropped sharply by adolescence, where they represented less than a third.

This echoes national trends: boys often struggle earlier, while girls’ difficulties spike during teenage years.

Acceptance rates were high – 77% of referrals were taken on – much better than the rejection rates often seen in CAMHS.

That means these school-based teams are indeed catching children who might otherwise be left waiting.

Anxiety and depression: who felt it most?

When researchers looked at symptom scores, teenagers reported more anxiety and depression than younger children, and girls reported more than boys.

But ethnicity made no difference—children from minority backgrounds scored similarly to White children.

This suggests that, at least in this school-based model, barriers to access may be lower than in other services where minority groups often face inequities.

Parents and children don’t always agree

Here’s where things get striking.

Most young people rated their symptoms as below or just on the borderline for clinical thresholds.

But parents painted a bleaker picture: the majority believed their child’s difficulties met the clinical threshold for anxiety and broader emotional problems.

This mismatch isn’t unusual.

Past research shows parents sometimes underestimate their child’s distress when they’re young, but overestimate it during adolescence.

For clinicians, that means neither voice can stand alone – both perspectives must be woven together to see the full picture.

What schools can (and can’t) do

By taking in most referrals, MHSTs seem to be doing what they set out to: widen the doorway to early help.

Children don’t need a diagnosis, and support is right there in school – a familiar place that sidesteps the stigma of walking into a clinic.

Still, these are “low intensity” services.

Children with more complex needs were referred elsewhere.

And because the study was conducted during the pandemic, when school life was far from normal, it’s unclear how patterns will evolve post-COVID.

Why it matters

For parents, the study underscores a crucial point: if your child downplays their struggles, that doesn’t mean you’re imagining things.

And if they insist they’re struggling while you don’t see it, that matters too.

Mental health is experienced differently from the inside and the outside.

For schools and policymakers, the findings highlight the value of accessible, school-based care.

Teen girls and older students may especially need tailored approaches, while boys might benefit from earlier outreach before they disappear from the referral pipeline.

For clinicians, the lesson is clear: listen to both the child and the caregiver. Each sees through a different lens, and the truth lies in the overlap.

Takeaway

School-based mental health teams are quietly reshaping early intervention in the UK.

They don’t replace specialist services, but they may prevent some young people from ever needing them.

The classroom, it turns out, is not just a place for maths and English—it can also be the first lifeline in a young person’s mental health journey.

Reference

Robinson, E., Chapman, C., Orchard, F., Dixon, C., & John, M. (2025). Characteristics of young people referred for treatment of depression and anxiety in a school-based mental health service. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12526