The Broken Windows Theory is a criminological idea suggesting that visible signs of disorder (graffiti, litter, or broken windows) encourage further crime and antisocial behavior. First introduced by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in 1982, it argues that maintaining order in communities helps prevent serious crime. While it shaped policing strategies in the 1990s, it’s also been criticized for promoting aggressive policing and ignoring deeper social causes of crime.

Key Takeaways

- Definition: Broken windows theory suggests that visible disorde, like vandalism, can lead to more serious crime if left unchecked. It argues that maintaining public order helps prevent escalation.

- Origin: Proposed by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in 1982, the theory was introduced through an influential Atlantic article that shaped modern policing debates.

- Mechanism: The idea rests on social psychology – when people see signs of neglect, they perceive weaker social norms and are more likely to engage in antisocial behavior themselves.

- Application: The theory inspired “order maintenance” or “zero-tolerance” policing strategies, most famously used in New York City during the 1990s to reduce crime through strict enforcement of minor offenses.

- Criticism: Many experts argue that Broken Windows policies can lead to over-policing of marginalized communities and ignore deeper economic or social causes of crime.

What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

Broken windows theory proposes that visible signs of disorder, such as litter, or public drinking, can create an environment that encourages even more serious crime and antisocial behaviour.

In short, if small problems are ignored, bigger ones tend to follow.

They argued that when small signs of disorder are left unattended, they send a social signal that no one cares and that rule-breaking will go unpunished.

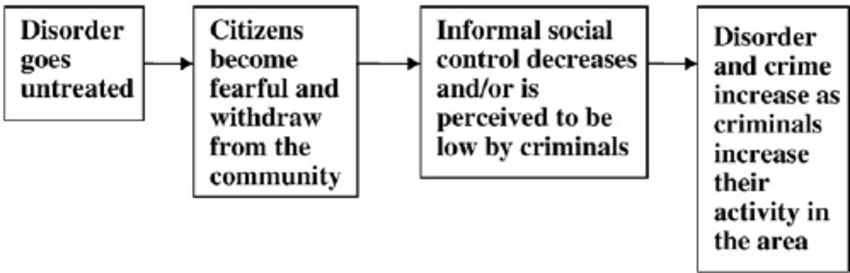

This creates a chain reaction:

-

Disorder sends a signal: Broken windows, graffiti, or loitering suggest that “no one is in charge.”

-

Residents withdraw: Law-abiding people start to feel unsafe and spend less time in public spaces.

-

Informal control breaks down: With fewer “eyes on the street,” community monitoring weakens.

-

Crime increases: The area becomes more attractive to offenders, leading to serious crime and further decay.

In this way, small disorders like vandalism and public drinking are seen not as harmless misdemeanors, but as early warning signs of deeper social breakdown.

Source: Hinkle, J. C., & Weisburd, D. (2008). The irony of broken windows policing: A micro-place study of the relationship between disorder, focused police crackdowns and fear of crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 503-512.

What Counts as “Disorder”?

BWT distinguishes between two main types of visible disorder:

Physical Disorder

At the heart of BWT is the idea that visible disorder communicates meaning. It acts like a signal that tells residents, visitors, and even potential offenders something about the community.

This refers to the visible decay of the physical environment, such as:

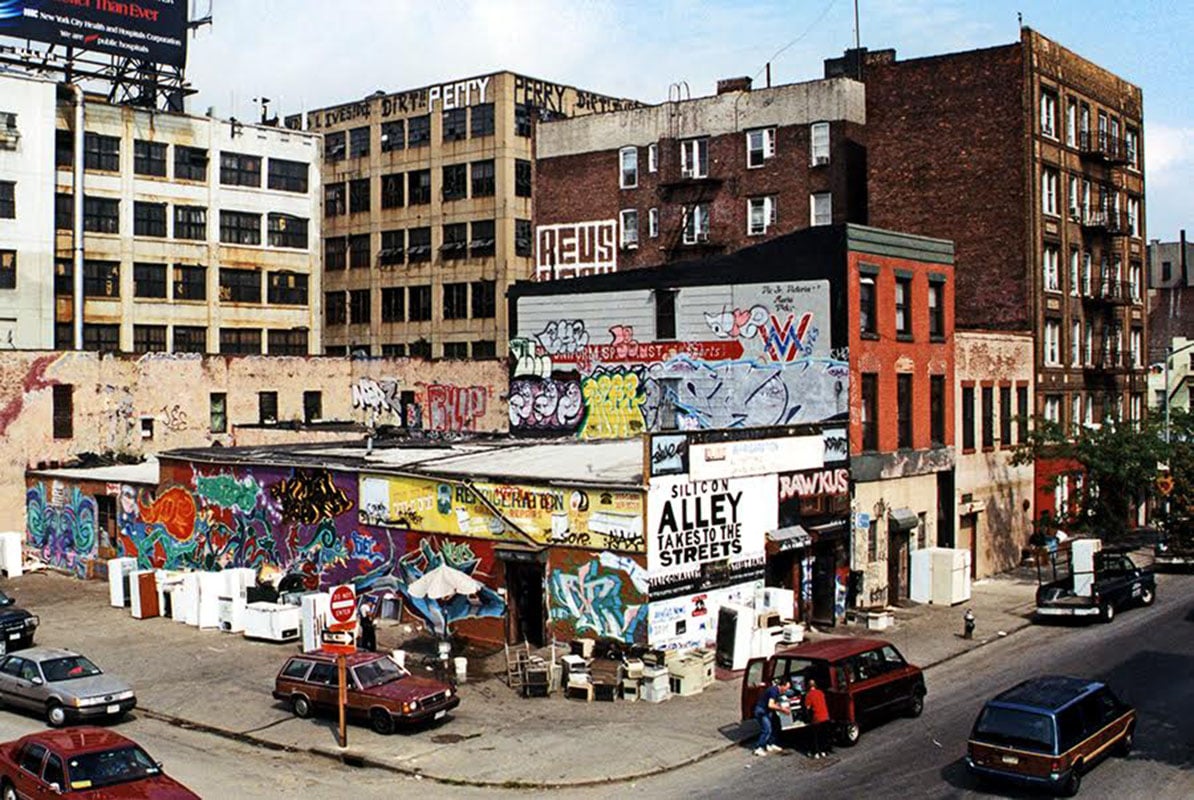

- Abandoned or run-down buildings

- Broken windows

- Graffiti and vandalism

- Litter, rubbish, or abandoned cars

When small acts of disorder go unchecked, it sends the message that no one cares or no one is enforcing the rules.

For potential offenders, this can make crime seem less risky, since they assume there’s a low chance of being caught.

For residents, it can signal a loss of community pride or authority, creating a sense of uncertainty and vulnerability.

Social Disorder

Disorder doesn’t just affect how people see their surroundings — it shapes how they behave.

When people perceive that others ignore social rules, they may begin to mirror that behaviour.

Social disorder refers to behaviours that make a place feel unsafe or uncontrolled, such as:

-

Loitering

-

Public drinking or drug use

-

Prostitution

-

Panhandling or harassment

-

Loud noise or public arguments

Both disorders send messages about the social norms of a community. An orderly, well-maintained area signals that rule-breaking isn’t tolerated. A neglected one suggests that people can get away with more.

Why Environment Matters

Academics explain the broken windows theory using three main ideas:

-

Social norms and conformity: People adjust their behaviour to fit what seems “normal” for an area. If disorder is visible, they may relax their own standards.

-

Routine monitoring: In safe, orderly places, both residents and businesses act as informal guardians – what Jane Jacobs called having “eyes on the street.”

-

Social signaling: Visible neglect tells potential offenders that the risk of getting caught is low, while a clean, cared-for environment communicates control and vigilance.

This means that the environment itself acts as a form of communication, shaping people’s sense of safety and influencing behaviour.

Examples of Broken Windows Policing

1969: Philip Zimbardo’s Introduction of Broken Windows in NYC and LA

In 1969, Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo ran a social experiment in which he abandoned two cars that had no license plates and the hoods up in very different locations.

The first was a predominantly poor, high-crime neighborhood in the Bronx, and the second was a fairly affluent area of Palo Alto, California. He then observed two very different outcomes.

In the Bronx, the car was vandalized within ten minutes.

A family first removed the radiator and battery, and within 24 hours, every valuable part had been stripped.

Soon after, random acts of destruction began: the windows were smashed, the seats were torn, and children started using the wrecked vehicle as a playground.

Meanwhile, the car in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week – until Zimbardo himself struck it with a sledgehammer. Only then did bystanders join in the destruction.

Zimbardo concluded that visible neglect invites further vandalism.

When something looks abandoned, people feel less constrained by social norms and more likely to act destructively.

1982: Kelling and Wilson’s Follow-Up Article

Thirteen years after Zimbardo’s study was published, criminologists George Kelling and James Wilson published an article in The Atlantic that applied Zimbardo’s findings to entire communities.

Kelling argues that Zimbardo’s findings were not unique to the Bronx and Palo Alto areas.

Rather, he claims that, regardless of the neighborhood, a ripple effect can occur once disorder begins as things get extremely out of hand and control becomes increasingly hard to maintain.

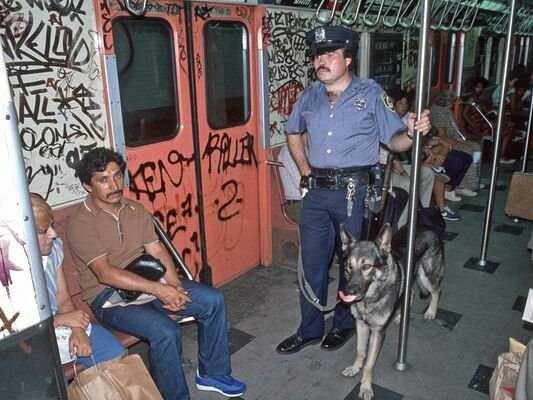

Early 1990s: Bratton and Giuliani’s implementation in NYC

The most famous application of the Broken Windows Theory took place in New York City during the mid-1990s.

-

Policy adoption: City leaders introduced order-maintenance policing, also known as zero-tolerance or quality-of-life policing. This strategy was based on the belief that targeting small crimes would help prevent bigger ones.

-

Key figures: Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton openly credited their approach to Wilson and Kelling’s 1982 essay. Bratton argued that the theory helped explain New York’s dramatic decline in crime rates.

-

How it worked: Police began strictly enforcing minor laws – including turnstile jumping, panhandling, public drinking, vandalism, loitering, and prostitution. Misdemeanor arrests rose sharply, increasing from about 133,000 in 1993 to over 205,000 in 1996.

-

Perceived success: Supporters claimed this crackdown was responsible for the city’s historic drop in violent crime. A 2001 study by George Kelling and William Sousa credited misdemeanor arrests with much of the decline.

-

Debate: Critics argued the fall in crime could be explained by other factors—such as changes in the drug trade, economic growth, or what researchers call mean reversion, where areas that once had very high crime rates naturally fall back to average levels over time.

Early 200s: Los Angeles

-

Bratton’s Appointment: In October 2002, Mayor James Hahn appointed William Bratton as police commissioner. Bratton had previously led New York City’s Broken Windows-inspired policing in the 1990s, which he credited for the city’s dramatic drop in crime.

-

Policy Focus: Bratton promised to end what he described as the LAPD’s “smile-and-wave” approach – where officers acknowledged problems but did not intervene.

Instead, he directed police to focus on visible signs of disorder.

Tackling graffiti became a key priority, as Bratton argued it reflected “community pride” and that eliminating it would signal to residents and potential offenders that disorder would not be tolerated. -

Community Impact: The LAPD expanded patrols in areas with visible decay, stepped up arrests for misdemeanors, and partnered with local organizations to clean up graffiti and litter.

Supporters argued that this visible enforcement improved public confidence and urban appearance, while critics contended that it deepened tensions between police and marginalized communities.

The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) Experiment

The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) program tested the Broken Windows idea on a national scale.

-

Design: Launched by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 1994, the project involved about 4,600 low-income families from five major cities – New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Boston.

-

Goal: Families were given housing vouchers that allowed them to move from high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods to cleaner, safer, and more stable communities.

-

Why It Mattered: This experiment directly tested whether living in a less disorderly environment would reduce crime, as the Broken Windows Theory predicts.

-

Findings: The results showed little to no change in criminal behavior. Moving to a better neighborhood didn’t automatically lead to less crime. Researchers concluded that while disorder may play a role, its effects are often overshadowed by other factors—like poverty, inequality, and social opportunity.

Criticisms of the Broken Windows Theory

The Broken Windows Theory (BWT) and its policy counterpart, order-maintenance policing (OMP) or zero-tolerance policing, have shaped crime prevention strategies worldwide.

However, decades of research and critical analysis have raised major doubts about the theory’s core assumptions, its causal claims, and its real-world consequences.

Critics argue that BWT misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime, fails empirically, and reinforces racial and class inequalities through over-policing.

Misinterpreting the Relationship Between Disorder and Crime

A central flaw of the Broken Windows Theory is its claim that visible disorder directly causes serious crime.

Critics suggest that this relationship is correlational, not causal, and that both disorder and crime are symptoms of deeper social conditions.

1. The Collective Efficacy Hypothesis

Sociologists Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush (1999) proposed that a third factor – collective efficacy – better explains why some communities experience higher crime rates.

Collective efficacy refers to the mutual trust and shared expectations among residents to maintain public order and intervene in problem situations.

Neighborhoods with strong social cohesion tend to have both lower disorder and lower crime, not because one causes the other, but because residents collectively manage their environment.

2. Empirical Evidence Against a Causal Link

A meta-analysis of 300 studies by O’Brien et al. (2019) found no direct causal connection between visible disorder and increased crime.

The authors noted that many earlier studies relied on flawed methods, failing to separate perception from reality or cause from correlation.

Disorder, they concluded, does not automatically lead residents to commit more crimes or even feel significantly less safe.

Similarly, David Thatcher (2003) argued that crime reductions in cities like New York during the 1990s were wrongly attributed to Broken Windows-style policing.

He and others (e.g., Metcalf, 2006; Sridhar, 2006) noted that the timing of falling crime coincided with other powerful social and economic shifts, including:

-

The waning of the crack cocaine epidemic

-

The Rockefeller drug law crackdowns

-

New York City’s late-1990s economic boom

Further, Bernard Harcourt (2009) showed that many cities without Broken Windows policies also saw sharp crime declines, while others that adopted them did not.

A pivotal study by Harcourt and Ludwig (2006) examined the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s relocation program, which moved inner-city residents to more orderly neighborhoods.

Contrary to BWT predictions, these residents did not commit fewer crimes after relocation—strong evidence that environmental “order” alone does not reduce criminal behavior.

Misunderstanding Why Crimes Are Committed

Broken Windows Theory assumes that people are rational actors deterred by the fear of getting caught.

In more “orderly” neighborhoods, informal social control supposedly increases the likelihood of detection, discouraging crime.

However, critics argue this assumption is overly simplistic. Many individuals engage in crime due to structural or personal factors such as:

-

Poverty and unemployment

-

Social pressure and inequality

-

Mental illness or addiction

-

Homelessness and lack of resources

These causes are often unrelated to the perceived likelihood of arrest.

By focusing on surface-level signs of disorder rather than structural inequality, Broken Windows policing risks punishing the symptoms of poverty instead of addressing its causes.

Over-Policing and the Expansion of Police Power

The application of BWT has often led to aggressive enforcement of minor offenses, producing a cycle of over-policing and criminalization of marginalized groups.

1. Escalation of Arrests and Coercion

In New York City, quality-of-life policing led to a 50% rise in misdemeanor arrests between 1993 and 1996.

People were detained for minor offenses like fare evasion, loitering, or sleeping on benches – sometimes spending up to 60 hours in custody.

Complaints of police brutality and misconduct soared during this period (Civilian Complaint Review Board reports).

Even Wilson and Kelling acknowledged that maintaining order sometimes required “informal or extralegal steps”, quoting officers who admitted, “We kick ass.”

These tactics often inflicted deep harm on low-income communities while showing little proven benefit in reducing serious crime.

Racial and Class Bias

Perhaps the most powerful criticism of BWT concerns its racialized and class-based impact.

1. Racial Profiling and Perception Bias

By giving officers broad discretion to decide what counts as “disorderly,” BWT allows implicit biases to shape enforcement.

-

Roberts (1998) argues that this discretion enables police to criminalize communities of color under the guise of maintaining order.

-

In a landmark study, Sampson and Raudenbush (2004) found that when shown identical neighborhoods with equal levels of graffiti and litter, participants perceived more disorder in areas with more Black residents.

-

This shows that racial stereotypes, not objective conditions, strongly influence perceptions of disorder – and by extension, where policing is concentrated.

The result is a cycle where minority neighborhoods are more heavily policed, leading to more arrests, reinforcing public perceptions of criminality, and justifying further surveillance.

2. Class Inequality and Criminalizing Poverty

BWT also disproportionately targets working-class and poor individuals.

Acts considered “disorderly” (e.g., sleeping in public, panhandling) are often survival behaviors, not crimes.

Yet they are punished more harshly in public spaces where visibility makes poverty criminal.

People without private spaces – especially the homeless – are thus more vulnerable to arrest and harassment.

Critics argue this transforms policing into a “war on poverty crimes” rather than a strategy for public safety.

Broken Windows to Stop-and-Frisk

Broken Windows policing has evolved into or justified more invasive practices, such as stop-and-frisk—brief, suspicion-based searches of individuals in public.

In 2008, New York police made 250,000 stops, but fewer than 0.1% led to the discovery of a firearm (Vedantam et al., 2016).

By 2011, police stopped 685,000 people, and nine out of ten were completely innocent (Dunn & Shames, 2020).

These figures highlight both the inefficiency of the method and its disproportionate targeting of young Black and Latino men.

Critics argue that Broken Windows provided the intellectual foundation for such intrusive practices—expanding police discretion at the cost of civil rights.

What alternative crime prevention strategies exist?

Alternative crime prevention strategies take a very different approach from Broken Windows policing.

Instead of focusing on punishing minor disorder, these methods aim to tackle the root causes of crime, reduce opportunities for offending, and strengthen communities through prevention and rehabilitation rather than punishment.

1. Tackling Social and Economic Inequality

Many sociologists argue that crime grows out of social inequality, unemployment, and poor living conditions – not broken windows or graffiti.

Approaches inspired by theories like Conflict Theory and Social Ecology focus on fixing these deeper problems.

-

Create Economic Opportunities: Offer good jobs and fair wages in struggling urban areas. When people have hope and opportunity, they’re less likely to turn to crime out of desperation.

-

Improve Neighborhood Conditions: Invest in affordable housing, clean public spaces, and safe infrastructure. Poverty, overcrowding, and neglected buildings can all contribute to crime.

-

Community Greening: Instead of using police to manage disorder, fund local projects that hire residents to clean up abandoned spaces or turn empty lots into parks. These programs build pride and community ownership while improving the environment.

2. Reducing Opportunities for Crime

Other strategies focus on making crime harder to commit by changing the environment or increasing supervision.

These ideas come from Routine Activity Theory and Situational Crime Prevention.

-

Situational Crime Prevention (SCP): Design environments so that crime is less tempting—add better lighting, lock doors, and improve surveillance. The idea is to make crime riskier, less rewarding, and harder to get away with.

-

Problem-Oriented Policing (POP): Instead of reacting to crimes after they happen, police identify specific local problems (like repeated break-ins or public drug use) and create tailored prevention plans with community input.

-

Civil Remedies (Third-Party Policing): Use laws and regulations to make landlords, bar owners, or other third parties help prevent crime. For example, nuisance abatement laws hold property owners accountable for maintaining safe, crime-free premises, while alcohol server liability encourages businesses to prevent excessive drinking and violence.

3. Strengthening Families and Communities

Crime is also linked to weak family bonds and lack of social support.

Strategies in this area focus on helping people build strong relationships and develop positive social behavior, starting early in life.

-

Support Families: Parenting programs can help strengthen communication and discipline within families, reducing the risk of youth offending.

-

Early Childhood Intervention: Provide education and support for children in high-risk households before problems escalate.

-

Youth Programs: Offer after-school and community activities that give young people structure, connection, and purpose.

-

Gender Socialization: Encourage boys and men to develop empathy, emotional regulation, and non-aggressive coping skills.

4. Reforming the Criminal Justice System

Finally, some approaches aim to transform the justice system itself by focusing on rehabilitation and reintegration instead of punishment.

-

Rehabilitation and Diversion: Provide education, job training, and treatment for substance abuse to help offenders build better lives. Diversion programs steer low-level offenders away from prison and into community support instead.

-

Community-Based Corrections: Use alternatives to incarceration—like probation, community service, or supervised programs—that keep people connected to their families and jobs.

-

Restorative Justice: Bring together victims, offenders, and community members to repair harm and rebuild trust. This approach focuses on healing rather than punishment, helping offenders take responsibility and reintegrate into society.

References

Branas, C. C., Cheney, R. A., MacDonald, J. M., Tam, V. W., Jackson, T. D., & Ten Have, T. R. (2011). A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(11), 1296–1306. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr273

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00124.x

Braga, A. A., Welsh, B. C., & Schnell, C. (2024). Disorder policing to reduce crime: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Criminology & Public Policy. https://crimejusticelab.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Criminology-Public-Policy-2024-Braga-Disorder-policing-to-reduce-crime-An-updated-systematic-review-and.pdf

Dunn, C., & Shames, M. (2020). Stop-and-frisk data. New York Civil Liberties Union. https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data

Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 28, 457–504.

Fondevila, G., Massa Roldán, R., Gutiérrez Meave, R., & Bonilla Alguera, G. (2023). Clandestine dumpsites and crime in Mexico City: Revisiting the Broken Windows Theory. Crime & Delinquency. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287231202634

Harcourt, B. E. (2009). Illusion of order: The false promise of broken windows policing. Harvard University Press.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. University of Chicago Law Review, 73(1), 271–320.

Herbert, S., & Brown, E. (2006). Conceptions of space and crime in the punitive neoliberal city. Antipode, 38(4), 755–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00473.x

Hunt, B. (2015, December 8). “Broken windows” theory can be applied to real estate regulation. Realty Times. https://realtytimes.com/agentnews/agentadvice/item/40700-20151208-broken-windws-theory-can-be-applied-to-real-estate-regulation

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Vintage Books.

Johnson, C. Y. (2009, January 12). Breakthrough on “broken windows.” The Boston Globe.

Katz, L. F., Kling, J. R., & Liebman, J. B. (2001). Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 607–654. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530151144113

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322(5908), 1681–1685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1161405

Kelling, G. L., & Sousa, W. H. (2001). Do police matter? An analysis of the impact of New York City’s police reforms. Manhattan Institute, Center for Civic Innovation.

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., & Hirschfield, P. (2001). Urban poverty and juvenile crime: Evidence from a randomized housing-mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530151144122

Metcalf, J. (2006, May 22). After the storm: The politics of broken windows policing. The New York Review of Books.

Morgan, R. E., & Kena, G. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018 (Report No. NCJ 253043). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/criminal-victimization-2018

O’Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Looking through broken windows: The impact of neighborhood disorder on crime and perceptions of crime. Annual Review of Criminology, 2, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092420

O’Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Broken (windows) theory: A meta-analysis of the evidence for the pathways from neighborhood disorder to resident health outcomes and behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 228, 272–282.

Plank, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Young, H. (2009). An application of “broken windows” and related theories to the study of disorder, fear, and collective efficacy in schools. American Journal of Education, 115(2), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1086/595669

Roberts, D. (1998). Killing the Black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. Vintage.

Roberts, D. E. (1998). Race, vagueness, and the social meaning of order-maintenance policing. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 89(3), 775–836. https://doi.org/10.2307/1144200

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 603–651. https://doi.org/10.1086/210356

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 67(4), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250406700401

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924

Sanbonmatsu, L., Ludwig, J., Katz, L. F., Gennetian, L. A., Duncan, G. J., Kessler, R. C., Adam, E., McDade, T. W., & Lindau, S. T. (2011). Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Final impacts evaluation. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pubasst/mtoFHUD.html

Sridhar, D. (2006, October 21). Why broken windows won’t fix crime. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/oct/21/usa

Stuster, J. (2001). Albuquerque Police Department’s Safe Streets program (Report No. DOT-HS-809-278). U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration / Anacapa Sciences, Inc. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/1491

Thacher, D. (2003). Order maintenance reconsidered: Moving beyond strong causal reasoning. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 94(2), 381–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/1144204

Vedantam, S., Keim, B., Boyle, T., & Glass, M. (2016, February 11). Is there a link between broken windows policing and stop-and-frisk? NPR. https://www.npr.org/2016/02/11/466575077/is-there-a-link-between-broken-windows-policing-and-stop-and-frisk

Vedantam, S., Shankar, R., & Spiegel, A. (2016, November 1). The problem with stop and frisk. National Public Radio (NPR). https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500104506/broken-windows-policing-and-the-origins-of-stop-and-frisk-and-how-it-went-wrong

Vilalta, C. J., López, P., Fondevila, G., & Siordia, O. (2020). Testing Broken Windows Theory in Mexico City. Social Science Quarterly, 101(3), 1019–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12784

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic Monthly, 249(3), 29–38.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 237–307). University of Nebraska Press.

Further Information

- Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249(3), 29-38.

- Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ, 28, 457.

- Fagan, J. A., Geller, A., Davies, G., & West, V. (2010). Street stops and broken windows revisited. In Race, ethnicity, and policing (pp. 309-348). New York University Press.