Exposure therapy is a technique used in the treatment of anxiety disorders like phobias or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Its goal is to help individuals overcome specific fears or sources of anxiety.

It works by exposing individuals to anxiety-provoking situations or stimuli in a gradual, controlled way to reduce fear.

For example, someone afraid of spiders would be systematically exposed to spiders under a therapist’s guidance.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or mental health condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this site.

The idea is that avoidance maintains anxiety, so controlled exposures teach the person to manage fear and decrease avoidance.

By creating a safe environment, the person learns that the triggers are not dangerous, so anxiety is decreased through new learning.

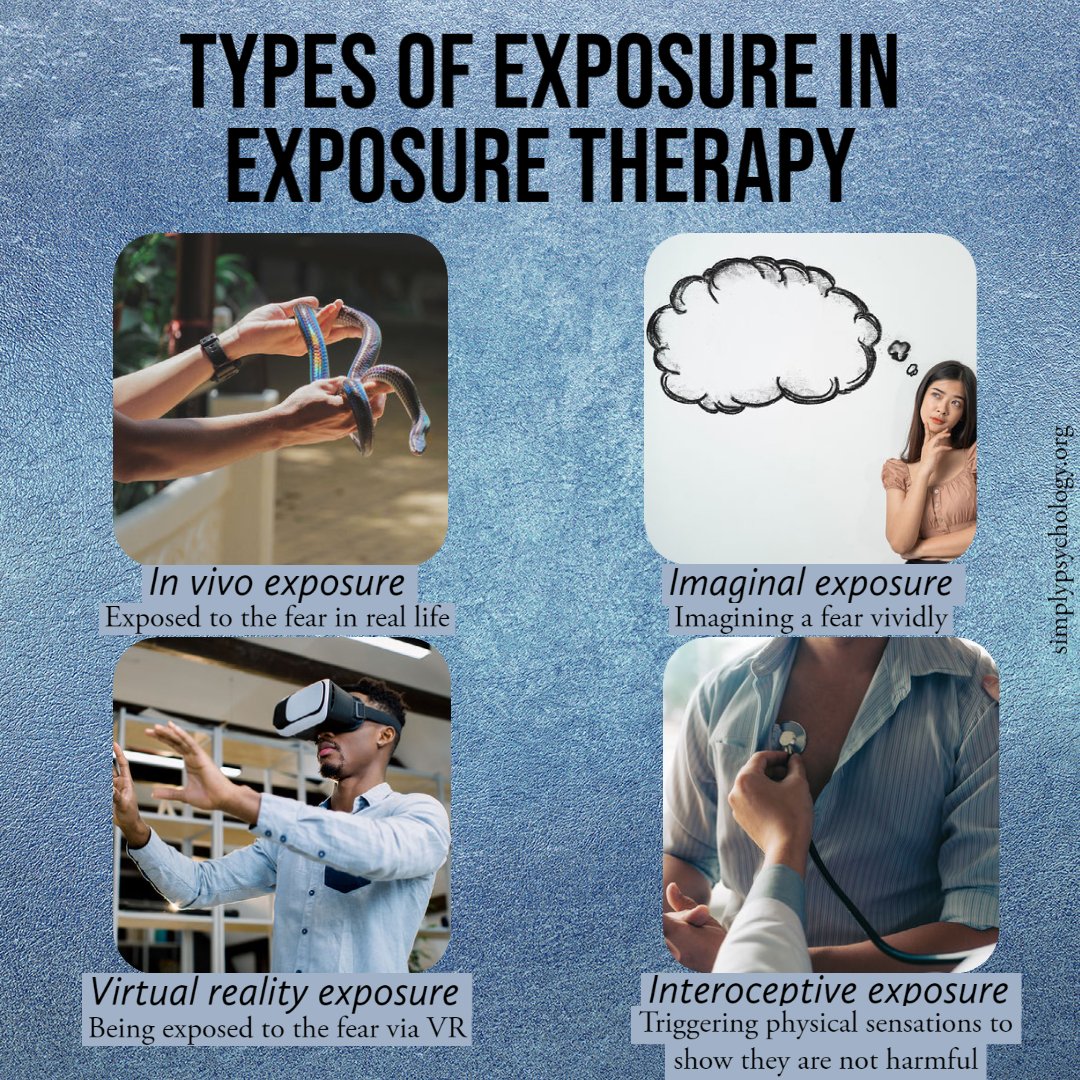

Types of exposure can include real-life interactions, imagination, virtual reality simulated exposures, or intentionally bringing on bodily sensations like dizziness. It is often used within cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as well.

Key Points

- Definition: Exposure therapy is a cognitive-behavioral treatment that helps people gradually face feared situations, thoughts, or sensations in a safe and controlled way.

- Purpose: The goal is to reduce avoidance, lower anxiety, and build coping skills so that fear no longer controls daily life.

- Methods: Different approaches include real-life (in vivo), imagined, virtual reality, and physical-sensation (interoceptive) exposures, often tailored to each person’s needs.

- Effectiveness: Research shows exposure therapy works well for phobias, PTSD, OCD, panic disorder, and social anxiety, with lasting improvements for many people.

- Considerations: While highly effective, it can feel challenging at first, so it’s important to work with a qualified therapist who can guide and adapt the process safely.

What Can Exposure Therapy Help With?

Exposure therapy is most often used for anxiety-related conditions where avoidance makes fears worse. Here are some common examples:

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): Exposure may involve facing everyday worries directly, such as resisting reassurance-seeking or postponing “what if” thinking, helping individuals reduce constant anxiety.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Therapists may guide people to revisit traumatic memories through safe imaginal exposure or practice approaching trauma reminders (like crowded places or loud noises) to lessen distress.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): Exposure and response prevention (ERP) helps individuals face feared thoughts (e.g., germs) while resisting compulsions (e.g., excessive handwashing), reducing the power of obsessions.

- Phobias (including agoraphobia): A person might start by imagining the feared object or place—like spiders, heights, or open spaces—and then gradually work toward real-life encounters to weaken the fear response.

- Panic disorder: Exposure may involve intentionally triggering feared physical sensations, such as dizziness or a racing heart, to show that these bodily reactions are not dangerous.

- Social anxiety disorder: Therapy can help by gradually practicing feared situations—such as making small talk, speaking up in meetings, or attending social events—until confidence grows and anxiety decreases.

Types of Exposure Therapy

According to the American Psychological Association, some of the variations of exposure therapy include:

In vivo exposure

In vivo exposure involves directly facing a feared object, situation, or activity in real life. For example:

- Going to the supermarket if someone has a fear of supermarkets.

- Seeing and going into a car for someone who is fearful of cars.

- Attending a party for someone who gets anxious at parties.

This type of exposure is likely to be used if the fear someone has is something that can be directly experienced at any time, thereby providing more opportunities to practice.

Imaginal exposure

In imaginal exposure, the individual is asked to vividly imagine and describe the feared stimulus, typically using present-tense language and including details about both external (sights, sounds, and tastes) and internal (thoughts and emotions) cues.

This may work best for someone with PTSD since they can re-imagine the sights, sounds, and emotions of being in a traumatic situation.

Imaginal exposure is useful for those who cannot expose themselves to the feared situation directly. It can also be useful as a stepping stone toward in vivo exposure. For instance, someone with a fear of spiders could vividly imagine a spider until they feel comfortable seeing a spider in person.

Virtual reality exposure

In recent years, technology has made it possible to use virtual reality devices during exposure therapy. This can be especially useful in situations when it is difficult to experience the trigger in vivo.

For example, someone with a fear of flying could use a flight simulator to help expose them to flying, where it may be impractical to go on a flight in person.

Interoceptive exposure

Interoceptive exposure involves deliberately triggering a physical sensation to show that it is harmless.

For instance, someone who is afraid of feeling light-headed because they think it means they’re having a stroke may be instructed to stand up quickly to trigger this sensation to show it is harmless.

Likewise, someone with panic disorder may fear an increased heart rate as they think it may result in a panic attack, so they may be structured to run in place to purposely increase their heart rate to show that a panic attack will not occur.

Techniques

Exposure therapy can be delivered in several ways, depending on the nature of the fear or disorder.

Some methods are general, such as graded exposure, flooding, or systematic desensitization, which gradually or directly confront fears.

Others are trauma-focused, including Prolonged Exposure (PE), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET).

Graded exposure

This method introduces feared situations step by step, starting with the least distressing and moving up a “fear hierarchy.”

It can involve real-life, imagined, virtual reality, or body-focused (interoceptive) exposures.

For example, someone afraid of crowds may begin by imagining one, then looking at crowd pictures, before eventually entering a busy place.

Flooding

Unlike graded exposure, flooding begins with the most feared situation. For example, a person with crowd anxiety might be taken directly into a busy place after learning relaxation skills.

It can reduce fear quickly, but because it is very intense, most clients and therapists prefer gradual methods.

Systematic desensitization

This combines exposure with relaxation techniques like deep breathing or muscle relaxation.

Clients progress through a hierarchy of feared situations while practicing relaxation, gradually replacing fear with calm responses. The process is slower but can feel more manageable.

Prolonged exposure (PE) therapy

A structured form of CBT, PE is widely used for PTSD. Sessions (usually 8–15) include psychoeducation about PTSD, breathing retraining, real-life exposure to avoided situations, imaginal exposure to traumatic memories, and processing of the emotions and thoughts that arise.

Between sessions, clients practice exposures and listen to recordings of their trauma narratives. The goal is to reduce avoidance and help the person regain a sense of safety and control.

Exposure and response prevention (ERP)

ERP is the gold-standard exposure method for OCD. The person is exposed to feared triggers (e.g., dirt) but prevented from performing their usual compulsion (e.g., washing hands).

Over time, this breaks the cycle between obsession and compulsion.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

In EMDR, the client recalls traumatic memories while focusing on external stimuli such as the therapist’s finger movements. This process helps reprocess the memory and reduce its emotional intensity.

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET)

NET helps people place traumatic events into the context of their broader life story.

By building a chronological “life narrative” that includes both traumatic and positive experiences, clients can process trauma while strengthening their sense of identity and resilience.

How Exposure Therapy Works

Anxiety is often maintained through the cycle of avoidance. When people avoid feared situations, they feel temporary relief, but over time, their fears grow stronger.

Exposure therapy works by breaking this cycle—helping individuals face what they fear so the anxiety naturally decreases.

It is believed that there are six primary ways exposure therapy may help people:

- Extinction: Exposure weakens the learned fear response by showing that the feared stimulus does not lead to the expected negative outcome. Over time, this reduces or eliminates the fear.

- Habituation: Repeated exposure gradually lowers emotional and physical reactivity, making the fear easier to tolerate.

- Self-efficacy: Facing fears in a controlled way builds confidence in one’s ability to cope with difficult situations.

- Emotional processing: Exposure helps replace unrealistic beliefs about danger with more balanced ones, reducing fear-driven thinking.

- Memory reconsolidation: When fear memories are recalled in a safe setting, they become flexible and can be “updated” with new, non-threatening information.

- Integration: New, less threatening experiences are incorporated into the person’s overall memory system, helping them form a more adaptive understanding of themselves and their fears.

How Effective Is Exposure Therapy?

Below are some of the key findings supporting the use of exposure therapy for anxiety disorders:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

A 2013 study found clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among male and female veterans of all war eras and those with combat-related and non-combat-related PTSD.

The results also indicated that prolonged exposure effectively reduced depressive symptoms in these individuals (Eftekhari et al., 2013).

Another study examined the effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy for active-duty soldiers and found there was a significant reduction in self-reported PTSD symptoms (Reger et al., 2011).

Social anxiety disorder

Virtual reality exposure therapy has been shown to be effective for those with public speaking anxiety, decreasing catastrophic belief expectancy and distress, and increasing perceived performance quality (Linder et al., 2021).

Another study found that exposure therapy was effective in treating social anxiety, with no significant difference in effect sizes between virtual reality, in vivo, or imaginal exposure (Chesham et al., 2018).

There were shown to be substantial reductions in social anxiety and considerable improvements in affective, behavioral, and cognitive experiences of stuttering (Scheurich et al., 2019).

Phobias

A review into phobias found that most phobias respond robustly to in vivo exposure therapy, with few studies obtaining a response rate of 80-90% (Choy et al., 2007).

Another review found evidence that virtual reality exposure therapy is an effective treatment for phobias, concluding that this is also a useful tool to combat these fears (Botella et al., 2017).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Exposure therapy has been supported for the treatment of OCD. Exposure and response prevention is seen as one of the first-line treatments for this condition (Law & Boisseau, 2019).

A study randomized patients with OCD to receive either in vivo exposure and response prevention, a type of antidepressant (clomipramine), or a combination of both.

For those who completed the study, 86% in the exposure group improved on measures examining the frequency and severity of obsessions and compulsions, compared with 48% in the antidepressant group and 79% in the combined treatment group (Foa et al., 2005).

Panic disorder

A 2018 study found that a three-session therapist-guided exposure treatment was effective at treating panic attacks in a group of eight participants.

Six of the participants saw a reduction in symptoms, and four showed remissions. Although this is a small sample size, it suggests that exposure therapy can be effective for those with panic disorder (Bergmark Hall & Lundh, 2019).

Limitations of Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy is highly effective, but it is not without challenges:

- Emotional distress: Confronting feared situations can trigger strong anxiety, which may temporarily worsen symptoms before they improve.

- Dropout risk: Because the process is uncomfortable, some individuals struggle to complete treatment, reducing its overall effectiveness.

- Trauma reactivation: For people with a history of trauma, exposures may trigger distressing memories, so careful assessment and adaptation are needed to prevent retraumatization.

- Underlying issues: Anxiety and phobias may reflect deeper emotional or psychological problems that require additional therapeutic approaches.

Despite these limitations, exposure therapy is one of the most effective treatments for anxiety and phobias. Success depends on working with a qualified therapist who can tailor the process to individual needs.

Non-Trauma-Focused Alternatives

Some PTSD treatments do not require revisiting traumatic memories. Examples include Present-Centered Therapy (PCT), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

These approaches focus on building coping skills, improving relationships, and managing current stressors, offering effective options for those who may not benefit from exposure-based methods.

Frequently Asked Questions

When should exposure therapy be considered?

If you find you have an extreme physical and/or emotional response to the feared stimuli and it is interfering with your life in a negative way, such as negatively affecting work, school, relationships, or other activities, this may be a sign that you need to seek help.

How can I seek exposure therapy?

It can be useful to begin by speaking to your doctor if you think you may need help with your anxieties. They may recommend you take CBT sessions, which can incorporate a lot of exposure therapy.

If you want to find a specialist in exposure therapy, you can search online, making sure to use reliable sources to find the right person.

Ensure you check the therapist’s credentials and ask whether they implement exposure therapy in their treatment.

You should ask what type of exposure therapy they use and the techniques they use.

It may also be useful to ask about their experience, what their area of expertise is, and what they would plan to do if exposure therapy does not work.

What are some key considerations when thinking about having exposure therapy?

Although research strongly supports exposure therapy, its implementation is not widespread among therapists. Limited availability of specialized training and concerns about symptom exacerbation in certain conditions may contribute to this.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that exposure therapy can be highly challenging. Directly confronting fears entails experiencing physical and emotional discomfort.

There may be moments when you feel overwhelmed by the exposure techniques. In such cases, it’s important to communicate with your therapist about any concerns or the possibility of trying a less intense approach.

However, to fully benefit from the therapy, it’s necessary to push yourself beyond your comfort zone and anticipate a reduction in anxiety over time as you work through it.

References

Beaudoin, M. N., Moersch, M., & Evare, B. S. (2016). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with children’s social and emotional skill development: an empirical study of 813 problem-solving stories. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 35(3), 42-59.

Botella, C., Fernández-Álvarez, J., Guillén, V., García-Palacios, A., & Baños, R. (2017). Recent progress in virtual reality exposure therapy for phobias: a systematic review. Current psychiatry reports, 19(7), 1-13.

Brown, L. S. (2024). Refreshing, necessary exposure to the problem with exposure therapies for trauma: Commentary on Rubenstein et al. (2024). American Psychologist, 79(3), 344–346.

Brunet, A., Orr, S. P., Tremblay, J., Robertson, K., Nader, K., & Pitman, R. K. (2008). Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(6), 503-506.

Cashin, A., Browne, G., Bradbury, J., & Mulder, A. (2013). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with young people with autism. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(1), 32-41.

Chesham, R. K., Malouff, J. M., & Schutte, N. S. (2018). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety. Behaviour Change, 35(3), 152-166.

Choy, Y., Fyer, A. J., & Lipsitz, J. D. (2007). Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clinical psychology review, 27(3), 266-286.

Craske, M. G., Kircanski, K., Zelikowsky, M., Mystkowski, J., Chowdhury, N., & Baker, A. (2008). Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(1), 5-27.

Debiec, J., & Ledoux, J. E. (2004). Disruption of reconsolidation but not consolidation of auditory fear conditioning by noradrenergic blockade in the amygdala. Neuroscience, 129(2), 267-272.

Eftekhari, A., Ruzek, J. I., Crowley, J. J., Rosen, C. S., Greenbaum, M. A., & Karlin, B. E. (2013). Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA psychiatry, 70(9), 949-955.

Foa, E. B., Liebowitz, M. R., Kozak, M. J., Davies, S., Campeas, R., Franklin, M. E., Huppert, J. D., Kjernisted, K., Rowan, V., Schmidt, A. B., Simpson, B. & Tu, X. (2005). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of psychiatry, 162(1), 151-161.

Ghavibazou, E., Hosseinian, S., & Abdollahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of narrative therapy on communication patterns for women experiencing low marital satisfaction. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 195-207.

Hall, C. B., & Lundh, L. G. (2019). Brief Therapist-Guided Exposure Treatment of Panic Attacks: A Pilot Study. Behavior Modification, 43(4), 564-586.

Hundt, N. E., Ecker, A. H., Thompson, K., Helm, A., Smith, T. L., Stanley, M. A., & Cully, J. A. (2020). “It didn’t fit for me:” A qualitative examination of dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in veterans. Psychological Services, 17(4), 414–421

Kindt, M., Soeter, M., & Vervliet, B. (2009). Beyond extinction: Erasing human fear responses and preventing the return of fear. Nature Neuroscience, 12(3), 256-258.

Law, C., & Boisseau, C. L. (2019). Exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Current perspectives. Psychology research and behavior management.

Lindner, P., Dagöö, J., Hamilton, W., Miloff, A., Andersson, G., Schill, A., & Carlbring, P. (2021). Virtual Reality exposure therapy for public speaking anxiety in routine care: a single-subject effectiveness trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 50(1), 67-87.

Nader, K., Schafe, G. E., & Le Doux, J. E. (2000). Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature, 406(6797), 722-726.

Najavits, L. M. (2024). Beyond exposure: A healthy broadening of posttraumatic stress disorder treatment options: Commentary on Rubenstein et al. (2024). American Psychologist, 79(3), 347–349.

Reger, G. M., Holloway, K. M., Candy, C., Rothbaum, B. O., Difede, J., Rizzo, A. A., & Gahm, G. A. (2011). Effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy for active duty soldiers in a military mental health clinic. Journal of traumatic stress, 24(1), 93-96.

Rubenstein, A., Duek, O., Doran, J., & Harpaz-Rotem, I. (2024). To expose or not to expose: A comprehensive perspective on treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Psychologist, 79(3), 331–343.

Rubenstein, A., Doran, J., Duek, O., & Harpaz-Rotem, I. (2024). Some closure on exposure—Realigning the perspective on trauma treatment and finding a pathway forward: Reply to Brown (2024) and Najavits (2024). American Psychologist, 79(3), 350–351.

Scheurich, J. A., Beidel, D. C., & Vanryckeghem, M. (2019). Exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder in people who stutter: An exploratory multiple baseline design. Journal of fluency disorders, 59, 21-32.

Schiller, D., Monfils, M. H., Raio, C. M., Johnson, D. C., Ledoux, J. E., & Phelps, E. A. (2010). Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms. Nature, 463(7277), 49-53.

Soeter, M., & Kindt, M. (2015). An abrupt transformation of phobic behavior after a post-retrieval amnesic agent. Biological Psychiatry, 78(12), 880-886.

Wachen, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Evans, W. R., Morris, K., & Cole, A. (2019). Massed versus spaced exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(4), 18m12309.