Sigmund Freud didn’t exactly invent the idea of the conscious versus unconscious mind, but he certainly was responsible for making it popular, and this was one of his main contributions to psychology.

Freud (1900, 1905) developed a topographical model of the mind, describing the features of the mind’s structure and function.

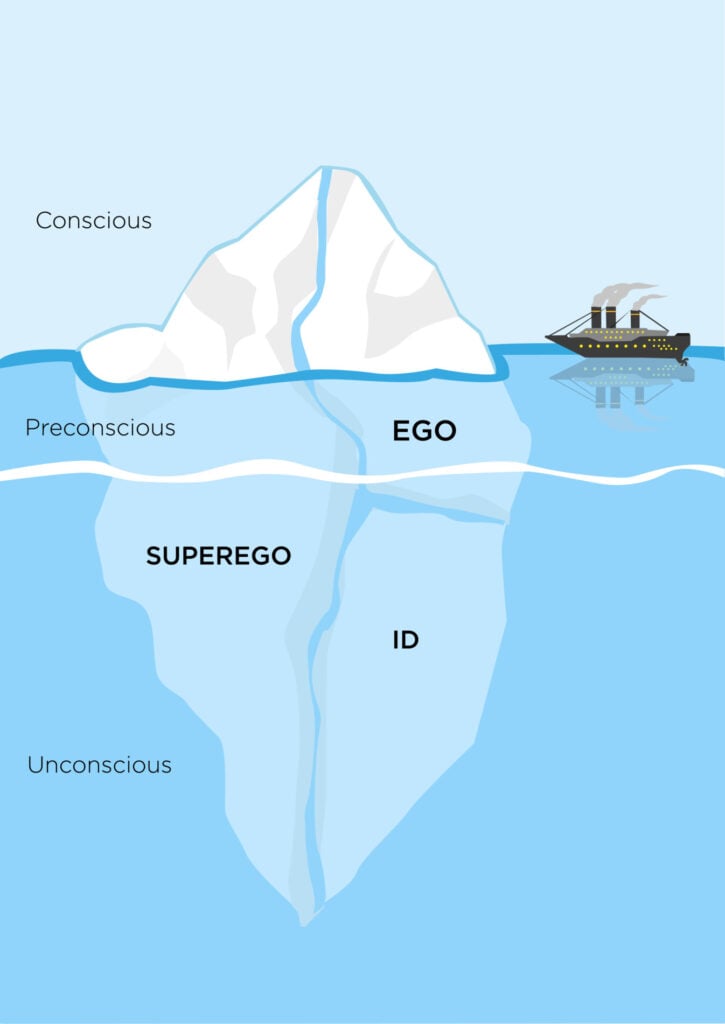

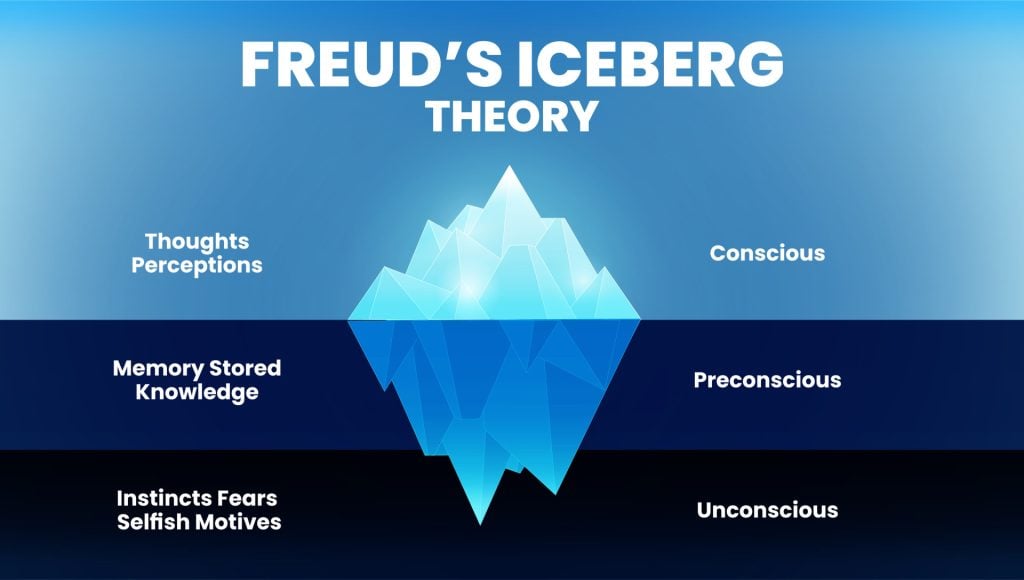

Freud used the analogy of an iceberg to describe the three levels of the mind: conscious, preconscious, and unconscious.

This model divides the mind into three primary regions based on depth and accessibility of information:

Freud’s conception of consciousness can be compared to an iceberg because, much like an iceberg, the majority of an individual’s mind exists below the surface, hidden from immediate view.

Iceberg Theory

Freud’s iceberg theory metaphorically represents the mind’s three levels: the conscious (visible tip of the iceberg), the preconscious (just below the surface), and the unconscious (vast submerged portion).

The mind has three levels: the conscious (what we know now), the preconscious (easily accessible memories), and the unconscious (deep desires and memories that influence behavior but remain largely inaccessible).

Freud (1915) described the conscious mind, which consists of all the mental processes of which we are aware, and this is seen as the tip of the iceberg. For example, you may be feeling thirsty at this moment and decide to get a drink.

Preconscious Mind

The preconscious contains thoughts and feelings that a person is not currently aware of, but which can easily be brought to consciousness (1924). It exists just below the level of consciousness, before the unconscious mind.

The preconscious is like a mental waiting room, in which thoughts remain until they “succeed in attracting the eye of the conscious” (Freud, 1924, p. 306).

This is what we mean in our everyday usage of the word available memory.

For example, you are presently not thinking about your mobile telephone number, but now it is mentioned you can recall it with ease.

Emotional Content

Mild emotional experiences may be in the preconscious, but sometimes traumatic and powerful negative emotions are repressed, hence not available in the preconscious.

In common language, “subconscious” is often used more generally to describe thoughts or feelings operating below the level of conscious awareness, without the nuanced distinctions of Freudian theory.

However, within the context of Freud’s model, “preconscious” (German translation: Unterbewusstsein) has a more specific and distinct meaning.

According to Freud (1915), the unconscious mind is the primary source of human behavior. Like an iceberg, the most important part of the mind is the part you cannot see.

While we are fully aware of what is happening in the conscious mind, we have no idea what information is stored in the unconscious mind.

The unconscious mind acts as a repository, a ‘cauldron’ of primitive wishes and impulses kept at bay and mediated by the preconscious area.

Our feelings, motives, and decisions are powerfully influenced by our past experiences, and stored in the unconscious.

Unconscious Mind

In psychoanalysis, the unconscious mind refers to that part of the psyche that contains repressed ideas and images, as well as primitive desires and impulses that have never been allowed to enter the conscious mind.

Freud viewed the unconscious mind as a vital part of the individual.

It is irrational, emotional, and has no concept of reality, so its attempts to leak out must be inhibited.

Content contained in the unconscious mind is generally deemed too anxiety-provoking to be allowed in consciousness.

It is maintained at an unconscious level where, according to Freud, it still influences our behavior.

The unconscious mind comprises mental processes inaccessible to consciousness but that influence judgments, feelings, or behavior (Wilson, 2002).

Sigmund Freud emphasized the importance of the unconscious mind, and a primary assumption of Freudian theory is that the unconscious mind governs behavior to a greater degree than people suspect. Indeed, the goal of psychoanalysis is to make the unconscious conscious.

The unconscious contains all sorts of significant and disturbing material which we need to keep out of awareness because they are too threatening to acknowledge fully.

The unconscious mind acts as a repository, a ‘cauldron’ of primitive wishes and impulses kept at bay and mediated by the preconscious area.

Unconscious Influences on Behavior

Much of our behavior, according to Freud, is a product of factors outside our conscious awareness.

People use a range of defense mechanisms (such as repression or denial) to avoid knowing their unconscious motives and feelings.

The unconscious mind acts as a repository, a ‘cauldron’ of primitive wishes and impulses kept at bay and mediated by the preconscious area.

The Process of Repression

For example, Freud (1915) found that some events and desires were often too frightening or painful for his patients to acknowledge and believed such information was locked away in the unconscious mind.

This can happen through the process of repression.

Freud recognized that some physical symptoms may have psychological causes.

Hysteria (sometimes known as conversion hysteria) is a physical symptom with no physical cause.

However, the ailment is just as real as if it had but is caused by some underlying unconscious problem.

Psychosomatic disorders are a milder version of this.

Instincts and the Unconscious

The unconscious is seen as a vital part of the individual; it is irrational, emotional, and has no concept of reality, so its attempts to leak out must be inhibited.

The unconscious mind contains our biologically based instincts (eros and Thanatos) for the primitive urges for sex and aggression (Freud, 1915).

Freud argued that our primitive urges often do not reach consciousness because they are unacceptable to our rational, conscious selves.

Freud believed that the influences of the unconscious reveal themselves in various ways, including dreams, and slips of the tongue, now popularly known as Freudian slips.

Freud (1920) gave an example of such a slip when a British Member of Parliament referred to a colleague with whom he was irritated as “the honorable member from Hell” instead of from Hull.

Critical Evaluation

Early Skepticism

Initially, many psychologists were skeptical of Freud’s idea that mental processes could operate at an unconscious level.

Behaviorists, in particular, rejected the concept because it could not be observed or measured objectively.

For psychologists seeking scientific rigor, the unconscious mind was frustratingly vague and untestable, making it incompatible with the empirical standards of early experimental psychology.

Bridging Psychoanalysis and Modern Psychology

Over time, however, the gap between psychology and psychoanalysis has narrowed.

Research in cognitive psychology and social psychology has provided empirical support for unconscious processes.

For instance:

-

Procedural memory (Tulving, 1972) allows individuals to perform tasks automatically, such as riding a bike or typing, without conscious awareness.

-

Automatic processing (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Stroop, 1935) demonstrates how attention and perception can operate unconsciously.

-

Implicit social cognition (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995) shows that people hold unconscious attitudes and biases that influence judgment and behavior.

These findings confirm that unconscious processes play a real and measurable role in shaping human thought and behavior.

The Adaptive Unconscious

Modern research has moved beyond Freud’s original conception to the idea of an adaptive unconscious (Wilson, 2004).

This contemporary view suggests that unconscious processes are not primarily repressed emotions or impulses, but rather efficient cognitive mechanisms that allow the brain to function automatically and quickly.

Freud (1915) saw the unconscious as a single entity – a repository of repressed desires and conflicts.

In contrast, current psychological models view the mind as composed of multiple specialized modules that have evolved to handle different tasks outside of awareness.

Evidence from Cognitive Science

Examples of these unconscious modules include:

-

Universal grammar (Chomsky, 1972): an innate, unconscious system that enables humans to recognize and generate grammatical sentences.

-

Facial recognition systems: which allow people to identify faces rapidly and effortlessly without conscious reasoning.

These examples highlight how unconscious processes operate independently, performing complex computations that support perception, language, and decision-making.

From Repression to Efficiency

Freud believed that unconscious material was repressed to protect individuals from anxiety or conflict.

The modern view, however, emphasizes efficiency rather than repression – suggesting that most information processing occurs outside awareness simply because conscious attention is limited.

As Wilson (2004) notes, the mind operates most effectively by delegating high-level cognitive tasks to unconscious systems, allowing consciousness to focus on immediate, novel, or complex challenges.

References

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American psychologist, 54(7), 462.

Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. S.E., 4-5.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition 7: 123- 246.

Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious. SE, 14: 159-204.

Freud, S. (1924). A general introduction to psychoanalysis, trans. Joan Riviere.

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological review, 102(1), 4.

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology, 18(6), 643.

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory, (pp. 381–403). New York: Academic Press.

Wilson, T. D. (2004). Strangers to ourselves. Harvard University Press.