If you or a loved one has recently received an autism diagnosis, you might be navigating a maze of confusing terms.

Is it a learning disability? A learning difficulty? What does “high functioning” actually mean?

You are not alone in this confusion. For decades, history and old diagnostic manuals blurred the lines between these concepts. But modern research is painting a very different picture.

According to renowned experts, autism and learning disabilities are distinct experiences—though they can happen at the same time.

This guide cuts through the jargon to explain exactly how they differ, why your “IQ score” might be misleading, and why experts are moving away from labels like “high functioning” entirely.

The Short Answer: No, But They Can Co-Occur

Let’s start with the most important fact: Autism is not a learning disability.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects how you communicate, process sensory information, and interact with the world.

A learning disability (often called an Intellectual Disability or ID in clinical terms) specifically involves significant difficulties with learning new skills and managing daily life independently.

Professor Francesca Happé, a leading researcher in cognitive neuroscience, explains that while these two conditions are different, they do overlap.

- Historical Confusion: Decades ago, it was assumed that most autistic people had a learning disability.

- The Real Numbers: Modern research suggests that while co-occurrence is common (estimates vary, but often sit around 30% for clinically diagnosed adults), the majority of autistic people do not have an intellectual disability.

Key Takeaway: You can be autistic and have a high IQ, an average IQ, or a learning disability. As Prof. Happé notes, autism exists at all IQ levels.

Understanding the “Spiky Profile”

If autism isn’t a lack of intelligence, what is it?

Dr. Amy Pearson, a developmental psychologist and expert in neurodiversity, argues against looking at autism through a “lens of incompetence.”

Instead of seeing it as a list of deficits, she suggests viewing it as a difference in how the brain is wired.

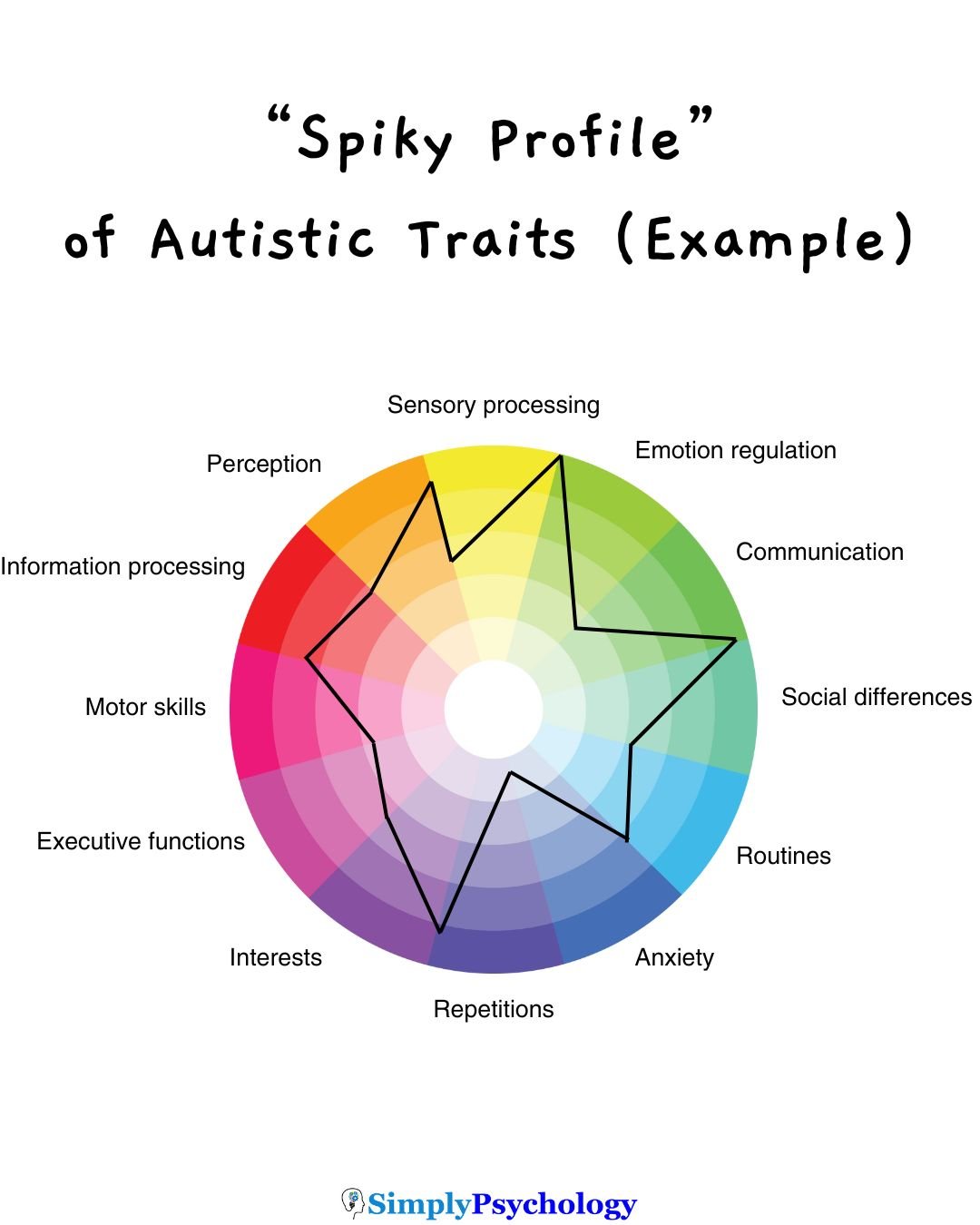

She describes the autistic experience as having a “Spiky Profile.”

In a neurotypical person (someone without autism), skills tend to be relatively flat or even. If they are “average” at math, they are likely “average” at reading and social skills.

In a Spiky Profile, you might see:

- Incredible Strengths: Exceptional vocabulary, deep focus, or pattern recognition.

- Specific Struggles: Difficulty with sensory overload, executive function (planning), or auditory processing.

Dr. Pearson emphasizes that judging a person based on a single “functioning label” (like low-functioning or high-functioning) is “vague” and often considered rude.

A person might be able to write a PhD thesis (high competence) but be unable to cook a meal without overwhelming sensory pain (high support need).

Why “High IQ” Doesn’t Mean “Mild” Autism

One of the most dangerous myths is that if you have a high IQ or good verbal skills, your autism is “mild” or you don’t need support.

Dr. Felicity Sedgewick, whose research focuses on autistic women and girls, challenges this idea. Her work highlights a hidden crisis among those often labeled as “cognitively able.”

The Cost of Compensation Prof. Happé and Dr. Sedgewick discuss a concept called “Compensation” (often related to masking).

This is when an autistic person uses their intellect to logically “solve” social situations that don’t come naturally.

- You might force eye contact because you know you “should.”

- You might script conversations in your head before having them.

The Result? While you might look like you are coping well on the outside, the internal effort is exhausting.

Dr. Sedgewick points out that mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, can actually be more pronounced in autistic people without cognitive impairments.

Expert Insight: Being “clever” doesn’t make the autism go away; it often just means you are working ten times as hard to hide it.

It’s Not a Deficit, It’s a Mismatch

If you are struggling, it is easy to feel like something is “wrong” with you. Dr. Pearson encourages us to flip the script using the Social Model of Disability.

She argues that many of the difficulties autistic people face aren’t caused by their brains being “broken,” but by a mismatch between their needs and the environment.

- Example: If you struggle in a loud office, is it because you have a “sensory deficit,” or because the office is designed for people who filter out noise differently?

Dr. Pearson notes that “functioning labels” are dehumanizing because they ignore this context. When we classify someone as “low functioning,” we often ignore their potential.

When we classify someone as “high functioning,” we ignore their struggle and deny them support.

Conclusion: Embracing the Difference

Autism is a distinct neurotype, not a learning disability. While some autistic people do have co-occurring learning disabilities that require specific support, many others do not.

The work of Dr. Pearson, Dr. Sedgewick, and Prof. Happé teaches us that we need to stop looking at linear scales of “severity.”

Instead, we must recognize the Spiky Profile: a unique combination of strengths and support needs that varies from person to person.

Your worth is not defined by your productivity, your IQ score, or your ability to act neurotypical. It is defined by your unique perspective and humanity.

Next Steps: How to Advocate for Yourself (or Your Child)

If you feel your specific needs are being ignored because of an IQ score or a “high functioning” assumption, try these steps:

- Map Your Spiky Profile: Instead of telling people “I’m autistic,” list your specific spikes. (e.g., “I am excellent at data analysis, but I cannot process verbal instructions in a noisy room.”)

- Request Specific Accommodations: Move away from generic requests. Ask for noise-canceling headphones, written instructions, or a quiet workspace based on your specific profile.

- Check Your Energy: If you are “compensating” all day, you are burning energy. Schedule specific “downtime” where you do not have to mask or socialize.