Changes in routine can be especially challenging for autistic people because predictability helps them feel safe and in control.

Unexpected disruptions, like a canceled plan or a new environment, may trigger stress, anxiety, or meltdowns.

Understanding why routine matters, what difficulties arise, and how to support flexibility can make everyday life more manageable for autistic individuals and their families.

Why Routine Matters in Autism

Routines are profoundly important for autistic individuals, providing essential structure and stability in a world often perceived as unpredictable.

Predictability and safety

Routines offer comfort and predictability, lessening anxiety by reducing uncertainty and allowing mental and emotional preparation for upcoming events.

This predictability is a crucial coping mechanism against intolerance of uncertainty (IoU), which is strongly linked to elevated anxiety in autistic individuals.

Knowing what to expect fosters a sense of being “calm and centered”.

Cognitive and sensory regulation

Routines help minimize sensory overload and anxiety by structuring daily demands and preventing overstimulation.

Repetitive behaviors, like stimming, serve as calming emotional regulators. They also support executive functioning, reducing the cognitive load by making things one less thing to think about, especially when the brain struggles to habituate to new stimuli.

Varied experiences

Reliance on routine varies significantly among autistic individuals. Disruptions can cause reactions from “mildly annoyed but tolerable to angry scream-crying meltdown”, or even agitated or violent behavior.

As one autistic person shares, routines help her “keep in control of my life… know what’s going to happen and I feel in control and I feel calm, and this is what reduces my anxiety”.

Another individual highlighted feeling “devastated, like the world is going to end, when it gets disrupted”.

Why changes in routine can be hard

Changes in routine can be particularly challenging for autistic individuals due to a complex interplay of neurological differences, emotional responses, and cognitive processing styles.

Neurological basis

Autistic individuals often experience cognitive inflexibility, making it difficult to shift thoughts and actions to adapt to new or changing situations.

This is a core aspect of executive functioning deficits, which hinder planning, mental flexibility, and self-monitoring abilities.

When routines are disrupted, the amygdala, a brain region involved in fear and anxiety, may react atypically in autistic brains, remaining highly activated even after repeated exposure to a stimulus.

This can lead to a sustained physiological stress response, such as “fight (meltdown), flight (withdrawal), or freeze (shutdown)”.

Furthermore, sensory processing differences mean that unpredictable or dynamic stimuli can cause overwhelming sensory overload, making routine changes a source of significant distress.

Emotional impact

Routines function as “life preservers” in a world often described as “unpredictable, confusing, ever-changing”.

When these routines are disrupted, it can cause intense anxiety and distress, often linked to feeling uncertain.

Autistic people describe: “If our routine is disturbed, everything feels precarious, like the floor dropping out from under us”.

This profound sense of losing control can trigger emotional dysregulation, including meltdowns or shutdowns.

Difficulties in identifying and describing one’s own emotions (alexithymia), which is common in autistic individuals, can further complicate processing this distress.

Common situations where routines change

Changes in routine can be profoundly challenging for autistic individuals across various settings.

School and work

In school, changes like shifting classes, varying teacher expectations, timetable alterations, and managing unstructured free time present significant challenges.

Transitions to new grades or schools can trigger burnout. Even minor disruptions, such as a fire alarm or an accustomed seat being taken, are highly upsetting.

At work, frequent changes to hours or unexpected meetings are distressing, contributing to burnout and job retention issues.

Home life

Home routines offer a crucial “island of stability”. When these are altered, family plans, social invitations, or holidays disrupt predictability, causing anxiety.

Becoming a new parent, for instance, drastically disrupts sleep and routines, leading to overwhelm.

Even small household changes, like redecorating, a changed pasta recipe, or an unavailable washing machine, can be deeply unsettling.

Unexpected events

Unforeseen circumstances, such as illness, transport delays, or environmental disruptions, are especially difficult as they lack warning and control.

An autistic person remarked that “unexpected will hit much harder”. These often unobserved small changes can trigger an involuntary physiological stress response, demanding immense mental effort and causing exhaustion.

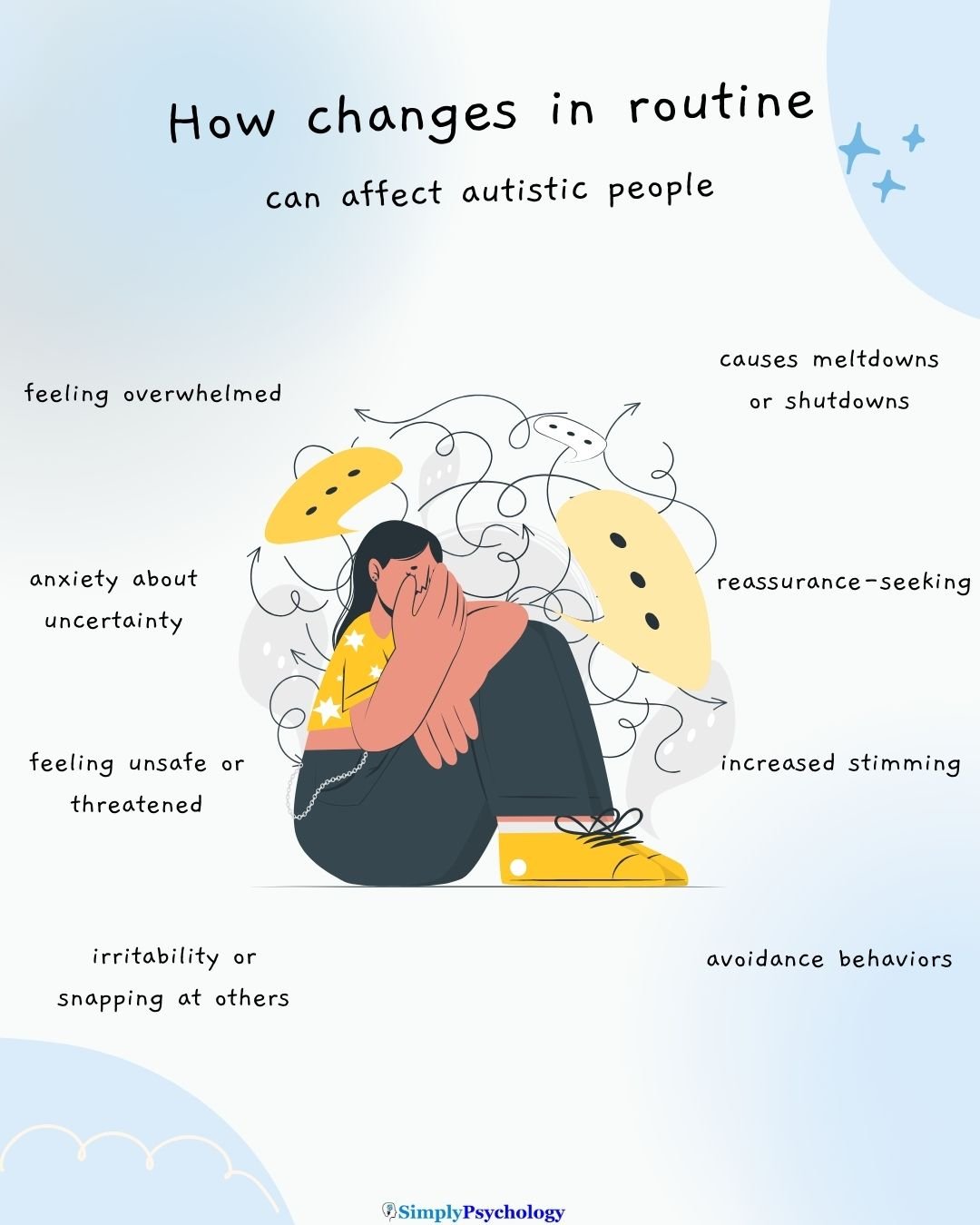

Signs of Distress During Routine Changes

Behavioural signs

- Meltdowns: yelling, crying, pacing, throwing things, increased or frantic stimming, repetitive questioning, or reassurance-seeking.

- Shutdowns: withdrawing, going quiet or non-responsive, mutism, moving slowly or seeming “frozen,” reduced motor coordination, or difficulty speaking.

- Withdrawal or avoidance: pulling away from social interaction, refusing tasks or transitions, resisting engagement, avoiding new or changed situations.

- Drop in functioning: difficulty completing usual tasks, less ability to plan or sequence steps, losing ability to mask or compensate.

Emotional/internal signs

- Heightened anxiety or worry: restlessness, agitation, sense of being “on edge.”

- Irritability or emotional fragility: becoming more easily upset, less able to tolerate frustration or small changes.

- Fatigue or sudden mental exhaustion: feeling drained, needing more rest, or unable to sustain effort.

- Emotional numbness or dissociation: feeling disconnected from surroundings, difficulty identifying or expressing feelings, sensory-numb or shut down internally.

How does this differ from general stress or frustration?

Reactions may appear more intense, prolonged, and less modifiable by “just calming down” because they stem from sensory, cognitive, emotional, and executive-function overload rather than just annoyance or inconvenience.

What might seem small or trivial to others can trigger a cascade of overwhelm (e.g., a minor schedule change leading to repeated anxiety, increased stimming, and then shutdown).

Recovery often takes longer: emotional regulation, return to routine, and cognitive capacity may be impaired for hours or days.

Coping strategies and support

Autistic individuals can employ various strategies to manage changes in routine, while caregivers, teachers, and friends can offer crucial support by understanding and adapting environments and communication styles.

For Autistic Individuals

Planning tools:

Visual supports, such as schedules, maps, labels, and calendars, are highly effective in clarifying verbal instructions, organizing tasks, and improving an individual’s ability to understand, anticipate, and participate in activities.

These tools, which can use photos, symbols, or words, are considered evidence-based practices for improving self-regulation skills.

Utilizing lists, rules, and step-by-step guides can further provide structure, making tasks one less thing to think about and reducing cognitive load.

Self-regulation techniques:

Routines and rituals are seen as well-being strategies used to manage overwhelming demands, recharge energy, cope with change, and reduce anxiety.

Stimming (e.g., repetitive movements) and deeply engaging with special interests serve as powerful emotional regulators and self-soothing mechanisms, helping to manage anxiety and sensory overload.

Taking sensory breaks in quiet spaces, using noise-cancelling headphones or sunglasses, and engaging in comforting activities like listening to music or playing familiar video games, helps manage overwhelm.

Developing self-awareness of emotional limits and learning to identify and label feelings through journaling or emotion charts can improve emotional control, especially for individuals experiencing alexithymia.

For Caregivers, Teachers, and Friends

Preparing for transitions:

Providing advanced notice and ample processing time for impending changes is crucial.

As an autistic individual described, “if it’s unexpected will hit much harder”.

Visual timetables and social stories are evidence-based interventions that clarify situations, supplement verbal instructions, and organize sequences of actions, thereby reducing anxiety.

Parents, for example, prepare their child in advance for routine changes, such as altering a route, by explaining what will happen and why.

Creating safe environments:

Clear, calm, and predictable communication is essential, as heightened emotional atmospheres can be intensely overwhelming.

Validating an individual’s feelings (“I understand this is very upsetting for you”) fosters trust and reduces the fear of rejection.

Adjusting the sensory environment, such as lowering lights or reducing background noise, can prevent distress.

Developing “Plan B” and “Plan C” contingencies helps manage unexpected disruptions and minimizes the stress of on-the-spot decision-making.

During moments of dysregulation, the focus should be on reducing external stimuli and demands, and increasing familiar, soothing inputs, such as weighted blankets or engaging in preferred activities.