The phrase “using autism as an excuse” often appears in conversations about accountability and behavior.

It raises a difficult question: when is someone genuinely struggling with autism-related challenges, and when are they avoiding responsibility by blaming their diagnosis? For many, the line feels blurred.

Autism can shape how a person communicates, reacts to stress, or manages daily tasks, which sometimes leads to misunderstandings or mistakes.

At the same time, being autistic does not mean someone is exempt from the impact of their actions on others.

This tension can cause friction in schools, workplaces, families, and friendships. Some people may view an explanation of autistic traits as “making excuses,” while others worry that autism is occasionally used to deflect criticism or accountability.

Exploring this phrase more closely helps clarify where understanding ends and excuse-making begins.

When Autism Is Used to Avoid Accountability

Using autism as an excuse implies an intentional avoidance of personal responsibility for harmful actions. This can involve dismissing feedback, refusing to adapt, or repeatedly blaming autism without making efforts to change.

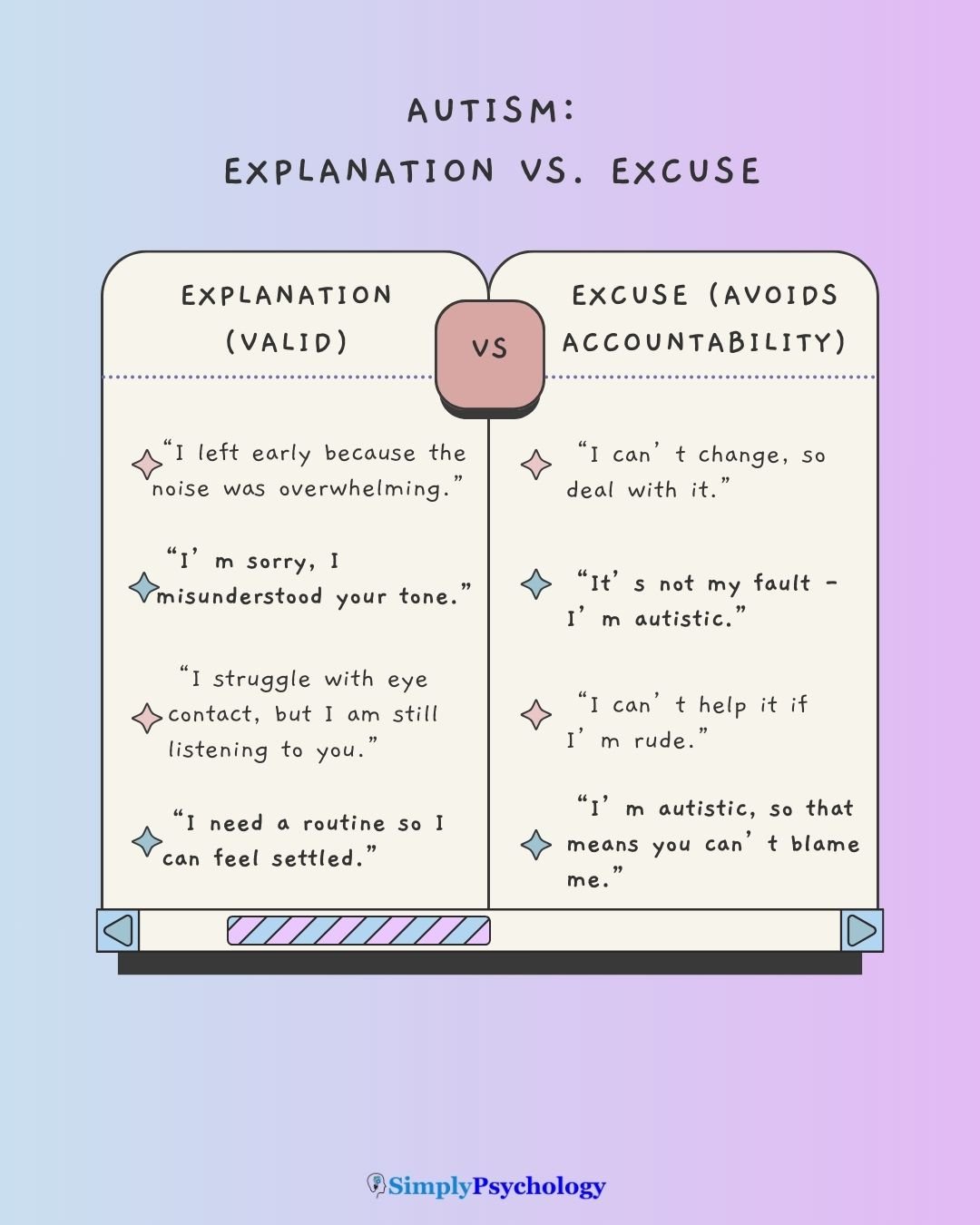

Examples of Excuses

- Blaming repeated harmful actions without trying to change: “I can’t help being rude; I’m autistic”—without apologizing or working on communication strategies.

- Using a diagnosis to shut down feedback: “You can’t criticize me, it’s just how my brain works,” said to avoid reflection or growth.

- Refusing to attempt accommodations or supports: Dismissing reminders, tools, or therapy with, “That won’t help, I’m autistic anyway.”

- Justifying deliberate cruelty: Using autism as a defense after intentionally insulting, bullying, or manipulating others.

- Avoiding all accountability for mistakes: Blaming every error (missed deadlines, conflicts, or broken agreements) on autism, without considering the impact on others.

When Explanations Are Misread as Excuses

Autistic people often provide genuine explanations for behaviors linked to their neurology—but these are sometimes dismissed as “excuses” by those who misunderstand autism.

Examples of Explanations

- Emotional regulation differences: Melting down after cumulative stress and being told, “You’re just using autism as an excuse for bad behavior.”

- Social communication differences: Missing sarcasm or saying something bluntly, then being told they are “hiding behind autism.”

- Sensory overload: Leaving a noisy classroom or workplace early, and being accused of “overreacting” or being “dramatic.”

- Executive functioning challenges: Forgetting an appointment or struggling with time management, which others label as “lazy” or “irresponsible.”

- Need for routine: Struggling with last-minute changes, which others see as “stubbornness” rather than a genuine autistic trait.

Autism Can Explain, But Not Excuse

Everyone, autistic or not, is accountable for their actions and choices.

Autism explains the reasons why certain difficulties arise, but it does not remove personal responsibility for harm caused.

An explanation provides context for behaviour, whereas an excuse seeks to avoid responsibility for it.

For example, missing a deadline due to executive dysfunction explains a genuine challenge; however, repeatedly blaming missed deadlines on autism without seeking accommodations or strategies can be perceived as an excuse.

Autistic individuals are generally expected to apologise and make efforts to mend relationships when their actions cause discomfort or offence.

Why the “Excuse” Label Is Harmful

Reinforces Negative Stereotypes

This label reinforces negative stereotypes, portraying autistic people as “manipulative” or “lazy” and unwilling to change.

It frames autism as a character flaw or a “bad trait” rather than a neurological difference.

This societal perception leads to autistic people being “judged, undervalued, and erased” and can suggest they are “getting away with” poor behaviour without consequence.

Some individuals falsely attribute their “egregious personality flaws” to autism, damaging the reputation of genuinely struggling autistic people. This misattribution hinders societal acceptance and understanding.

Emotional Consequences for Autistic People

The “excuse” label also has severe emotional consequences for autistic individuals. It can lead to internalised shame and self-hatred, as they feel their authentic autistic self is unacceptable.

This fear of negative judgment fosters a reluctance to disclose their diagnosis or self-advocate, anticipating disbelief (e.g., “you don’t look autistic”) or accusations of excuse-making.

Consequently, autistic people often resort to masking their traits to conform to neurotypical expectations.

This constant masking is exhausting and a crucial contributor to autistic burnout, leading to increased stress, anxiety, depression, and even suicidality.

Masking also prevents them from receiving appropriate support and can cause a loss of identity.

Distinguishing Between Traits and Bad Behavior

Distinguishing between genuine autistic traits that deserve understanding and behaviors that still require accountability involves recognising the neurological underpinnings of autism versus intentional harmful actions.

Autism-Related Challenges That Deserve Understanding

Certain behaviors are involuntary expressions of how autism shapes perception and regulation. These are not “bad behavior” but genuine differences in processing the world:

- Sensory sensitivities: Bright lights, loud noises, or strong smells can trigger meltdowns or shutdowns—physiological responses, not deliberate acts of defiance.

- Social communication differences: Missing sarcasm, speaking bluntly, or misreading body language are linked to neurological differences, not rudeness.

- Need for predictability: Routines help manage anxiety; distress over sudden changes reflects coping challenges, not manipulation.

These traits deserve understanding, not blame, and often benefit from accommodations such as sensory breaks, clear communication, or advance notice of changes.

Behaviors That Require Accountability

While autism can explain difficulties, it does not justify intentionally harmful choices. Autistic people, like anyone else, can act in ways that knowingly cause harm, and these actions require accountability. Examples include:

- Verbal or physical aggression intended to hurt others, beyond an involuntary meltdown.

- Exploitation or manipulation, when someone understands the impact of their actions and uses it to their advantage.

- Persistent harassment or bullying, even if triggered by frustration, when it continues despite being made aware of its harm.

- Breaking agreements or rules knowingly, not because of executive dysfunction, but because the person chooses to ignore them.

- Dishonesty to avoid consequences, rather than communication struggles.

The Grey Areas

Many situations don’t fall neatly into “trait” or “bad behavior.” For instance:

- An autistic student lashes out verbally during sensory overload—while the trigger is involuntary, the words may still wound others.

- Someone avoids responsibilities due to executive dysfunction but also doesn’t seek support or accommodations to improve.

- A meltdown leads to property damage, which is unintentional but still requires repair or restitution.

In these cases, the focus is on repair and growth: acknowledging harm, apologizing where possible, and building coping strategies to reduce future incidents.

The goal is not perfection but progress—recognizing that accountability and accommodation can coexist.

How to encourage healthy accountability

Encouraging healthy accountability in individuals with autism involves a dual approach, recognising both genuine autism-related challenges and the universal expectation of responsibility for one’s actions.

For Autistic People

Autistic individuals can cultivate healthy accountability by pairing explanations of their experiences with active steps towards improvement and repair. This involves:

- Communicating Challenges and Efforts: Phrases like, “I struggle with [e.g., understanding subtle social cues, managing sensory overload, or adapting to unexpected changes] because of my autism, but I am actively working on [e.g., using explicit communication tools, developing coping strategies, or seeking specific accommodations]” can be effective. This demonstrates self-awareness and a commitment to growth.

- Acknowledging Impact: When actions inadvertently cause distress, an autistic person can take responsibility by stating, “This wasn’t intentional, and I may not have fully grasped the impact at the time, but I take responsibility for the effect it had and want to understand how to make amends”. This separates intent from impact and focuses on repair, acknowledging that autism is an explanation, not an excuse for harmful behaviour.

For Families, Teachers, and Employers

Supporting accountability in autistic individuals requires a shift in perspective and proactive strategies:

- Offer Accommodations While Setting Clear Expectations: Provide clear, consistent rules and structures, as predictability is highly valued by many autistic people. Offer accommodations for sensory sensitivities, communication preferences, and the need for routines. Understand that challenges, like sensory overload, can trigger intense emotional reactions such as meltdowns or shutdowns.

- Encourage Problem-Solving Rather Than Labeling: Instead of labelling behaviour as “bad” or “disruptive,” consider it as dysregulation or an attempt to communicate unmet needs. Focus on identifying and addressing the underlying triggers and collaboratively developing coping strategies. Parents who participate in training often become less likely to believe their child’s problematic behaviour is intrinsic and more open to the idea of change.

- Model Compassion with Boundaries: Treat autistic individuals with added grace and provide a safe, non-judgmental environment. When an individual is overwhelmed or dysregulated, reduce demands and stimuli unless safety is an immediate concern, creating space for them to process and regulate. This approach embodies the “double empathy problem,” advocating for mutual understanding rather than placing the burden of adaptation solely on the autistic individual.