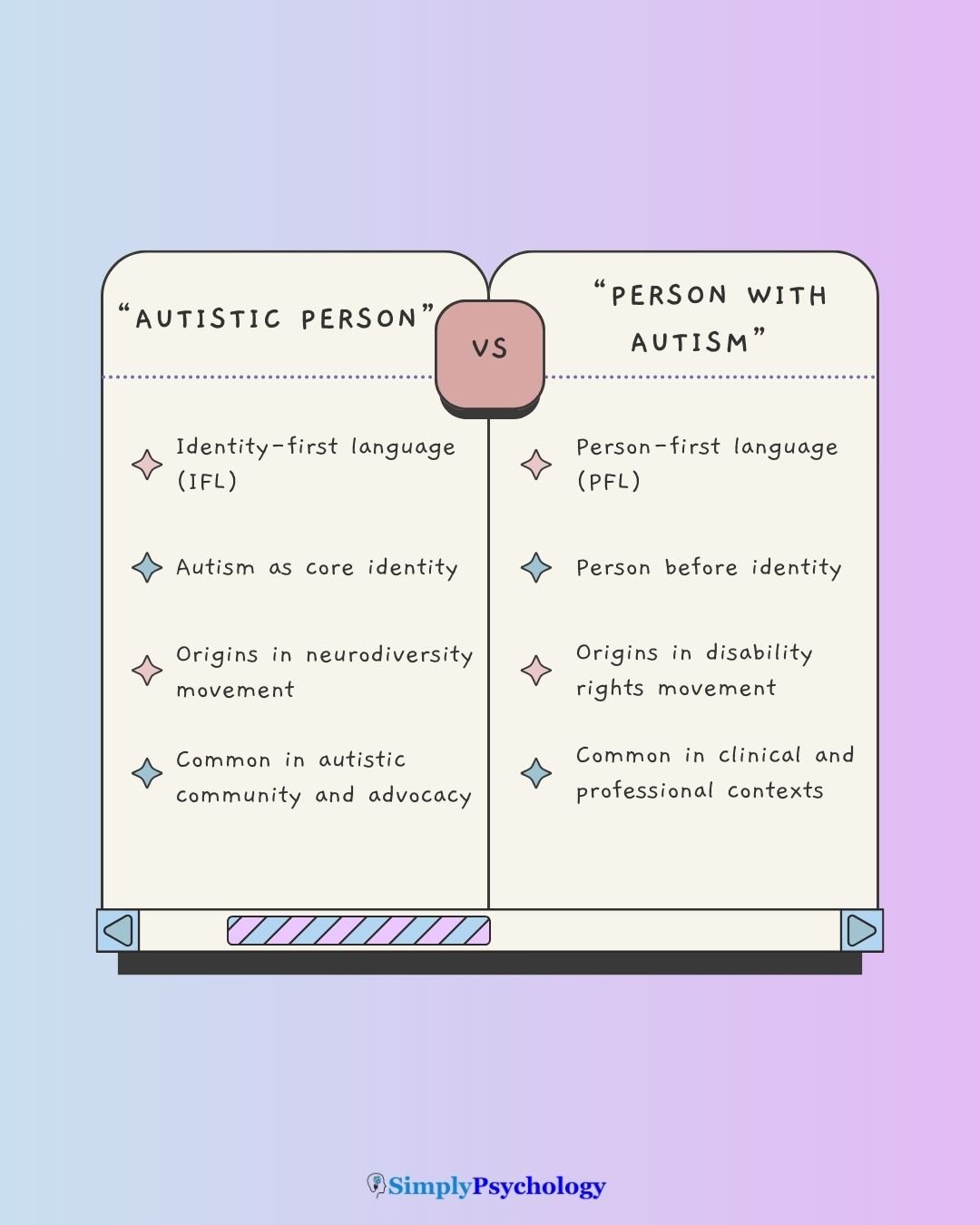

The phrase “person with autism” uses person-first language, emphasizing the individual before the condition, while “autistic person” uses identity-first language, highlighting autism as a core part of identity.

Which term is preferred depends on context, personal choice, and cultural factors. Understanding these differences helps us use respectful, inclusive language when talking about autism.

What’s the Difference?

Language shapes perception. The ongoing debate between calling someone an “autistic person” versus a “person with autism” reflects deeper ideas about identity, stigma, and respect.

These two terms—known as Identity‑First Language (IFL) and Person‑First Language (PFL)—carry distinct histories and connotations that matter in both personal and public discourse.

Person-First Language (PFL)

Definition: Person-first language frames autism as something a person has, not is—for example, “person with autism” instead of “autistic person”.

Origins: The roots of PFL trace back to the disability-rights movement in the late 20th century. Advocates promoted it to combat dehumanizing labels and emphasize personhood over diagnosis.

PFL became embedded in institutional language, including in U.S. laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act and style guidelines such as APA and AMA.

Identity-First Language (IFL)

Definition: Identity-first language places autism at the core of identity—“autistic person”—recognizing it as an essential part of who someone is.

Roots: IFL emerged from the neurodiversity and autistic self-advocacy movements. In the 1990s, these movements framed autism as a natural variation in human neurology rather than a disease to be cured.

It asserts that autism is inseparable from identity and that separating it can demean who autistic people are.

Preferences in the Autistic Community

Understanding language preferences in the autistic community helps us communicate with respect and clarity.

Research shows that preferences vary depending on the stakeholder group—autistic adults, parents, and professionals each bring distinct perspectives.

What Autistic Adults Say

A U.S. survey of 299 autistic adults found that an overwhelming majority preferred identity-first language like “I am autistic” instead of “a person with autism.”

For many, embracing “autistic” fosters a sense of pride, authenticity, and community belonging.

Parents, Professionals, and Mixed Views

Conversely, professionals, including educators and clinicians, often prefer person-first language, viewing it as more neutral or respectful.

Some parents also support person-first terms, though preferences can vary across cultural and linguistic contexts.

In one Dutch study, 82.5% of parents favored “person with autism,” while a majority of autistic adults leaned toward identity-first.

No One-Size-Fits-All

Given the complexity and diversity of preferences, the most respectful approach is simply to ask individuals how they prefer to be referred to.

One global study of 654 English‑speaking autistic individuals echoed this, recommending people inquire rather than assume.

This places communication and respect directly in the hands of each person and community.

Why Language Matters

Choosing between the terms “person with autism” and “autistic person” is more than semantics—it’s a reflection of how we view autism, shape identity, and influence social and institutional attitudes.

Thoughtful language can reduce stigma, affirm identity, and shape policy—and hearing directly from autistic individuals can be especially illuminating.

Reducing Stigma

Person‑First Language (PFL)—phrases like “person with autism”—emphasize personhood before the condition, aiming to humanize and lessen prejudice.

Many style guides, including APA and ASHA, support PFL to “reduce stigma, stereotyping, and prejudice toward people with disabilities”.

However, critics point out that PFL is often inconsistently applied—used more for children or for disabilities deemed more stigmatizing—potentially reinforcing stigma rather than alleviating it.

Affirming Identity

Identity‑First Language (IFL), such as “autistic person,” places autism at the heart of identity. Many self-advocates find this empowering.

One eloquent reflection puts it plainly: “It is impossible to affirm the value and worth of an Autistic person without recognizing … identity as an Autistic person … Referring to me as ‘a person with autism’ … denies who I am”.

This perspective aligns with the neurodiversity paradigm, which views autism as a natural variation in neurology—not a deficit.

The Role of Language in Policy and Research

Language also matters in policy and academic circles. How autism is labeled—whether as a condition to manage or a neurodiverse identity—can influence both funding priorities and public attitudes.

Moreover, advocacy groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) emphasize the power of language in shaping inclusive policies, arguing for autistic-led decision-making and terminology that reflects lived experience.

Practical Guidance for Everyday Use

Language is powerful—not just in meaning, but in connection. When choosing between “autistic person” and “person with autism,” context, audience, and individual preference guide respectful communication.

Here’s how to navigate these choices thoughtfully.

When Writing or Speaking Publicly

If your audience includes autistic individuals or is rooted in neurodiversity advocacy, identity-first language (“autistic person”) is generally the default, as many autistic adults and self‑advocates prefer terminology that affirms identity and belonging.

For clinical, academic, or mixed professional audiences—where style guides like APA or certain medical contexts still lean toward person-first language (“person with autism”)—that may be more appropriate unless you know community preferences otherwise.

Asking About Individual Preferences

If addressing someone directly, a simple, respectful approach works best: “Do you prefer ‘autistic person’ or ‘person with autism’?”

This practice centers individual dignity and autonomy and echoes the social model’s stance: best to ask, not assume.

Consistency in Writing

When writing for mixed or general audiences, aim for clear transitions. For example, you might introduce the terms—“Autistic people (also referred to as people with autism depending on preference)”—then select one and use it consistently throughout.

In more formal contexts, adapt to audience expectations: academic journals may require person-first, while advocacy blogs may use identity-first. The key is clarity—signpost shifts in terminology to avoid confusion and respect linguistic diversity.

Resources

National Autistic Society: How to talk and write about autism

NHS England: Making information and the words we use accessible

References

Buijsman, R., Begeer, S., & Scheeren, A. M. (2022). ‘Autistic person’ or ‘person with autism’? Person-first language preference in Dutch adults with autism and parents. Autism, 27(3), 788. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221117914

Keating, C. T., Hickman, L., Leung, J., Monk, R., Montgomery, A., Heath, H., & Sowden, S. (2022). Autism‐related language preferences of English‐speaking individuals across the globe: A mixed methods investigation. Autism Research, 16(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2864

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 27(2), 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221130845