Autistic individuals often tend to lean towards a bottom-up processing style. This means they may focus more on specific parts of information rather than integrating it holistically (top-down processing).

While this detail-focused cognitive style can lead to challenges in areas like interpreting complex social cues or facial expressions, it is increasingly understood not as a “deficit” but as a different way of processing information and experiencing the world.

This unique processing style can also contribute to strengths, such as enhanced perception of visual details and patterns.

Key Takeaways

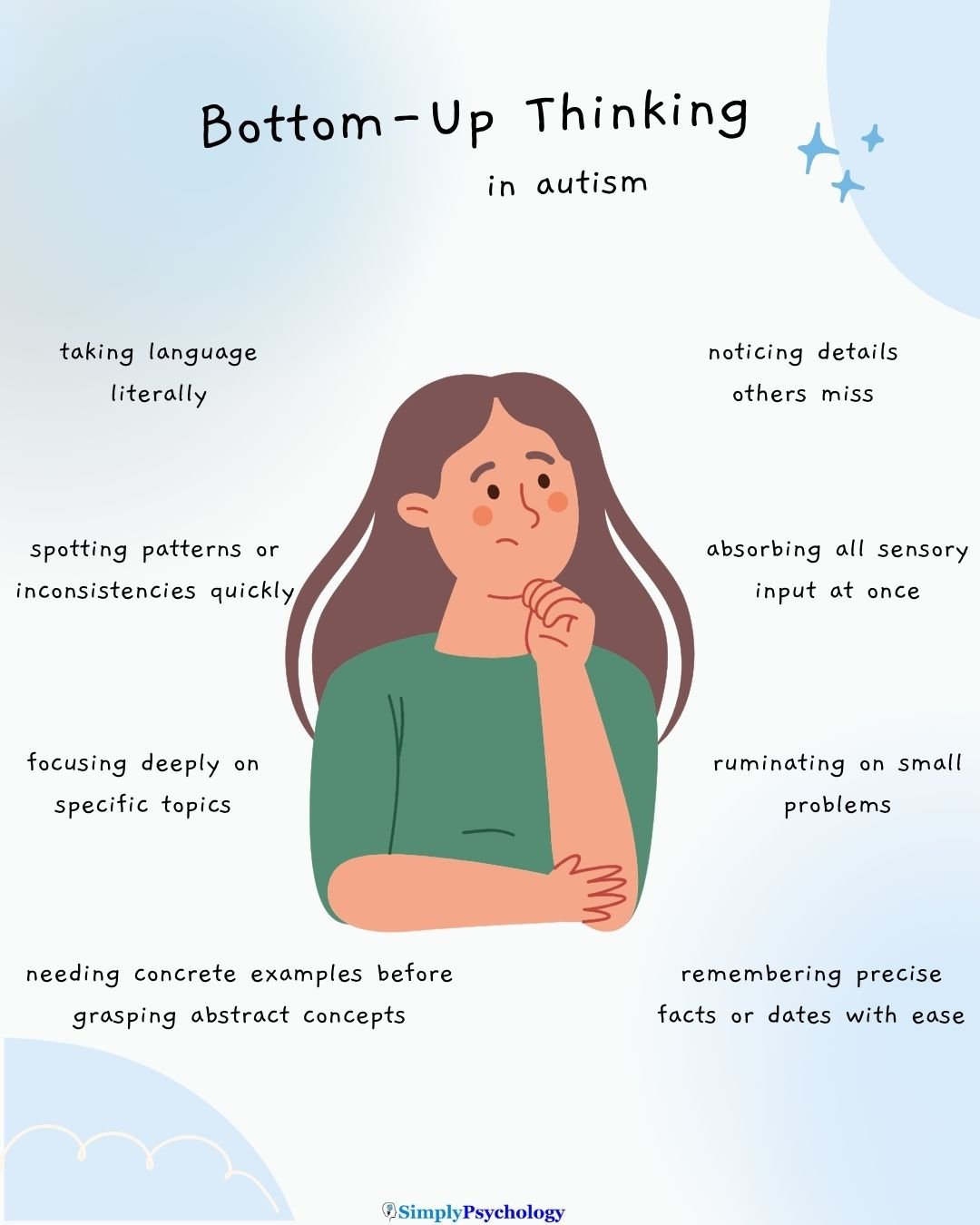

- Detail focus: Autistic individuals often process information from the ground up, noticing fine details before grasping the bigger picture, which can be both a strength and a challenge.

- Unique strengths: Bottom-up thinking supports abilities in pattern recognition, accuracy, creativity, and problem-solving, making it valuable in fields like research, design, and technology.

- Social differences: Focusing on details can make interpreting facial expressions, tone, and social context difficult, sometimes leading to misunderstandings in communication.

- Sensory impact: Processing all sensory input at once may cause overload, leading to stress, exhaustion, or autistic burnout if not managed effectively.

- Support strategies: Both autistic individuals and their environments can adapt—through visual tools, step-by-step learning, structured tasks, and sensory regulation—to make everyday life more manageable.

How Bottom-Up Processing Might Look in Real Life

- Spotting tiny details – Noticing small changes (like a crooked picture frame or a slight noise shift) before recognizing the bigger situation.

- Linking ideas differently – Thought processes may jump between details that feel logically connected internally, though they seem tangential to others.

- Taking in everything at once – Absorbing all sensory input (sounds, lights, textures) before filtering out what’s relevant, which can lead to overwhelm.

- Literal understanding of language – Interpreting idioms or abstract phrases word-for-word before grasping the figurative meaning.

- Learning through examples – Needing multiple concrete instances before forming an abstract or general concept.

- Detail-first child learning – Children may focus on sensory or factual details first, then gradually build up to broader meaning.

Strengths of bottom-up thinking

Below are some of the strengths of bottom-up thinking in autistic people:

Detail Detection and Accuracy

Autistic individuals may demonstrate superior abilities in detail detection and accuracy.

This can manifest as an enhanced ability to notice fine details, patterns, and subtle changes that others might miss.

For example, they may show superior performance on non-contextual perceptual tasks such as embedded figures or block-design tests.

Creativity and Problem-Solving

The detail-focused nature of bottom-up processing also fosters unique approaches to creativity and problem-solving.

Autistic people may be great at “connecting the dots” and creative problem-solving. Their capacity to perceive patterns and connections in unconventional ways may allow them to generate novel ideas that wouldn’t have occurred to others.

This enables thinking “outside the box” and approaching challenges with a different, often highly logical, perspective.

Real-World Examples

These strengths find application in various careers and hobbies:

- Research and Analysis: The ability to focus on narrow or mundane topics for extended periods can be a significant advantage in research fields. Their detail-oriented and analytical minds are well-suited for tasks involving data analysis and identifying root causes.

- Technology and Design: Strengths in visual-spatial skills and pattern recognition are beneficial for fields like coding, programming, and art/design.

- Special Interests: Autistic individuals’ highly focused or selective interests can lead to deep expertise and profound contributions in their chosen areas.

Challenges linked to bottom-up thinking

Bottom-up processing, while offering unique strengths, also presents distinct challenges for autistic individuals due to their detail-focused cognitive style:

Difficulty Seeing the “Big Picture”

Since autistic people tend to focus on individual details rather than integrating information holistically to form an overall meaning, this means they might be highly attuned to specific parts of information.

This can make it difficult to grasp the “big picture” or to summarize and generalize effectively.

It might also mean they may hyperfixate on a small problem and find it difficult to view the whole situation.

Social and Communication Differences

This detail-oriented processing can contribute to “context blindness”, making it challenging to understand the nuances of social situations.

Autistic individuals may struggle to interpret complex facial expressions, gestures, and tone of voice, leading to difficulties in pragmatic communication.

They might rely more on the literal meaning of words (semantics) over emotional tone (prosody).

This often plays into the “double empathy problem“, which posits that social misunderstandings are bidirectional.

Neurotypical people can also find it difficult to accurately empathize with autistic individuals’ emotions and perspectives, leading to mutual misinterpretations and confusion in relationships.

Sensory and Cognitive Overload

Processing a vast amount of detailed sensory input can lead to sensory overload, where environmental stimuli like sounds or light are experienced with magnified intensity and can even be physically painful.

The brain’s networks for integrating sensory information and regulating emotions may function differently, making it hard to manage emotional responses automatically.

This constant effort to process and make sense of overwhelming information, along with the taxing demands of masking (pretending to be neurotypical), frequently results in cognitive overload, exhaustion, and autistic burnout.

Supporting and adapting to bottom-up thinking

While you shouldn’t aim to change bottom-up thinking in autistic thinking, others can adapt to this type of thinking. Autistic people can also learn some tips to help them see the whole picture when it might help them.

Everyday Coping Strategies

For autistic individuals:

- Regulate sensory input: Use noise reducers, adjust lighting, or move to quieter spaces to avoid overload.

- Practice calming techniques: Mindfulness, deep breathing, or short meditations can reduce emotional sensitivity.

- Communicate needs: Share preferred ways of receiving information or responding in social settings.

For family, friends, and peers:

- Create an accepting environment: Validate feelings and give time to respond without pressure.

- Offer explicit communication: Be clear and direct in conversations; suggest possible responses to social cues if needed.

- Support sensory needs: Help adjust environments (e.g., lowering noise, finding quieter spaces).

Learning and Education

For educators and parents:

- Make abstract ideas concrete: Use visual supports like schedules, maps, labels, and symbols to link details to bigger concepts.

- Teach step-by-step: Break down social or emotional concepts with tools like social stories.

- Encourage participation: Use scaffolding—provide encouragement and gradual support while valuing active involvement.

For autistic learners:

- Practice skills directly: Repetition and structured practice help strengthen emotion regulation and learning strategies.

- Use visual tools: Graphic organizers, diagrams, or labeled cues can make learning clearer and easier to generalize.

Workplace Adaptations

For employers and colleagues:

- Structure tasks clearly: Break assignments into smaller steps with concise instructions.

- Provide consistency: Keep rules and expectations clear; prepare employees for changes when possible.

- Use visual strategies: Incorporate diagrams, written guides, and practice with feedback.

- Value strengths: Recognize skills such as pattern recognition, detail focus, and visual-spatial reasoning.

For autistic employees:

- Seek clarity: Ask for written instructions or task breakdowns when needed.

- Use personal organization tools: Checklists, visual planners, or reminder apps can support task management.

FAQs

How does bottom-up processing relate to anxiety, rumination, or executive-functioning difficulties?

Bottom-up processing, with its heightened focus on detail and raw sensory input, can leave autistic individuals vulnerable to cognitive overload and repetitive thought patterns.

Research indicates that insistence on sameness can drive repetitive negative thinking—like rumination and obsessing—which mediates a significant link to anxiety and depression in autism.

What misconceptions exist about bottom-up processing in autism?

Several prevalent myths mischaracterize bottom-up processing in autistic people:

– “Detail focus means lack of creativity.” In reality, many autistic individuals channel their detail-driven processing into original insights, pattern recognition, and creative thinking.

– “Autistic people don’t understand context at all.” Theories like Weak Central Coherence suggest a preference for parts over wholes—but this is a processing style, not an inability. Many autistic people simply arrive at meaning differently, by first collecting specific details and then building context.

– “Bottom‑up thinking is always limiting.” On the contrary, it’s a valuable cognitive style that supports strengths in pattern detection, factual memory, and nuanced sensory awareness.

Does bottom-up processing contribute to social misunderstandings?

Yes — bottom‑up processing can indeed contribute to social misunderstandings in autism.

For example, they may miss implied context or nonverbal cues that neurotypical people use intuitively, causing messages to be misinterpreted.

They might have difficulty inferring intentions without explicit information, which contrasts with the assumption-based, top‑down style more common in neurotypical communication.

References

Cooper, K., & Russell, A. (2024). Insistence on sameness, repetitive negative thinking and mental health in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 29(2), 424. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613241275468