Social cues – those subtle, unspoken signals in conversation and body language – can feel like a mysterious language. They include things like facial expressions, tone of voice, gestures, and implied meanings that most people pick up on instinctively.

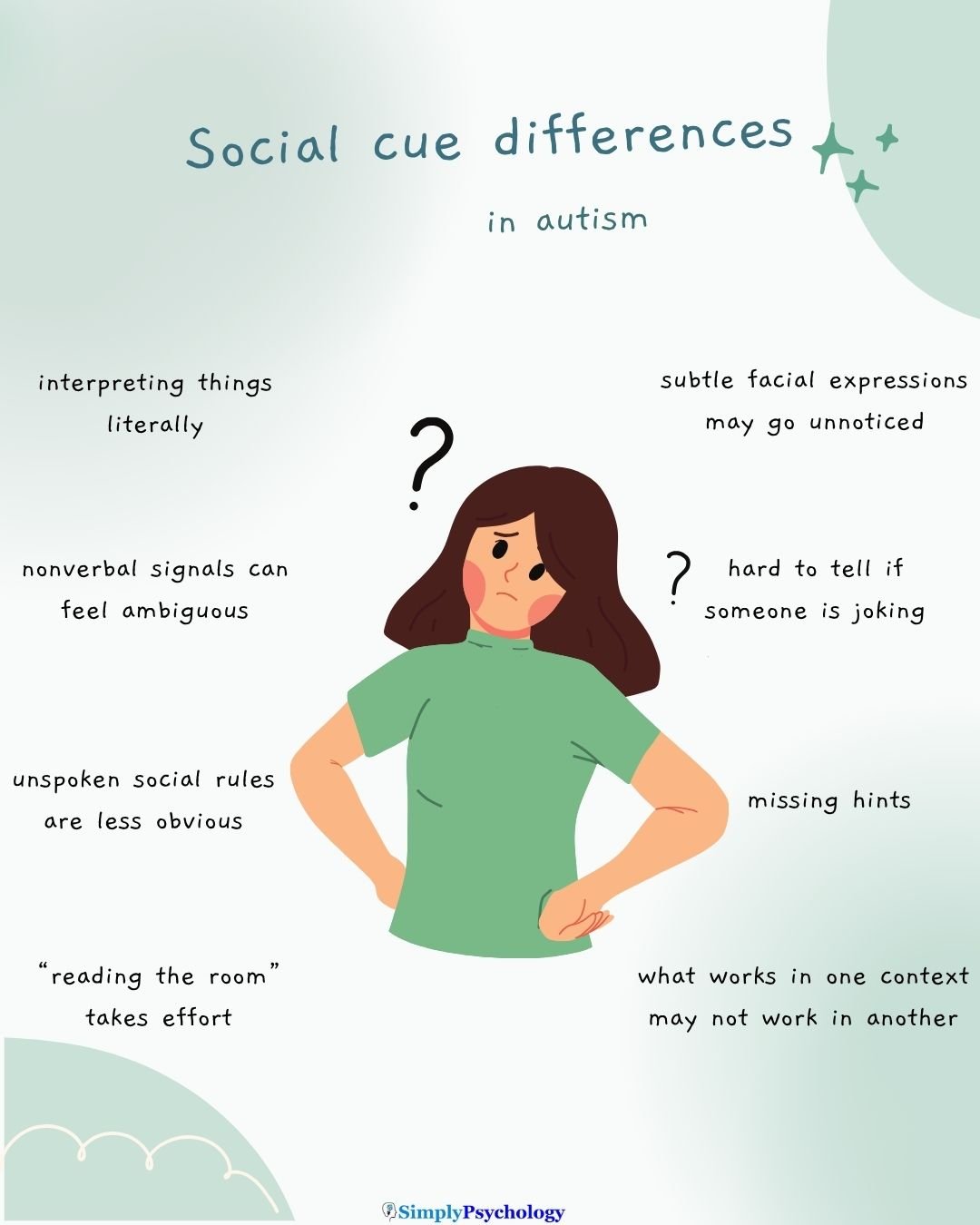

For many autistic individuals, however, these unwritten rules don’t come naturally. If you’ve ever felt lost trying to “read the room” or catch a hint, you are far from alone.

In other words, the struggle often isn’t you – it’s the way others respond to differences.

What Are Social Cues?

Social cues are the unspoken signals we use to express how we feel, what we want, or how we expect others to respond. These cues help guide conversation, show empathy, and maintain relationships—but they’re often subtle and unwritten.

For most neurotypical people, social cues are picked up naturally through observation and repetition. For many autistic individuals, however, these cues can feel vague, inconsistent, or even invisible—especially when no one explains them directly.

Common Examples of Social Cues:

- Facial expressions – A smile may suggest friendliness, while a frown might signal annoyance.

- Tone of voice – A flat tone may come across as disinterest; a rising tone might suggest a question or surprise.

- Body language – Crossing arms might signal discomfort; nodding often means agreement.

- Gestures – A thumbs-up for approval or a shrug to show uncertainty.

- Unspoken rules – Taking turns in conversation, not interrupting, or standing an appropriate distance apart.

Understanding these cues often requires interpreting context, emotion, and subtle shifts in communication—all of which can be challenging when your brain processes information more literally or differently.

Social cues can vary by culture, setting, and individual, making them even more unpredictable.

For autistic individuals, missing or misreading these cues isn’t a lack of awareness—it’s often because the “rules” are unclear or change depending on the situation.

Recognizing this isn’t about blaming one side or the other—it’s about increasing understanding for everyone involved.

Why Social Cues Can Be Challenging for Autistic People

For many autistic individuals, social cues aren’t instinctive—they’re often inconsistent, unspoken, or context-dependent. That makes them hard to recognize or interpret, especially when no one explains the “rules.”

These challenges aren’t about disinterest or a lack of empathy. They usually reflect differences in how autistic brains process information: more literally, more precisely, and often with a focus on content over subtext.

Here are some common difficulties:

1. Reading Facial Expressions and Body Language

Autistic people may not automatically recognize the meaning behind a raised eyebrow, crossed arms, or a forced smile. These subtle signs can be hard to decode without explicit context.

2. Interpreting Tone of Voice

Tone is often used to express sarcasm, playfulness, or annoyance—but when someone says “Great job!” in a flat or exaggerated tone, it may be unclear whether they mean it or not. Many autistic people focus on what is said rather than how it’s said.

3. Understanding Unwritten Rules

From how much eye contact is “normal” to when to pause or speak in a group, social rules are often assumed rather than taught. This “hidden curriculum” can leave autistic people feeling like they missed a secret lesson everyone else attended.

4. Navigating Metaphors and Indirect Language

Idioms like “spill the beans” or “hit the ground running” don’t make sense without prior knowledge. If you take language literally—as many autistic people do—these phrases can be confusing or misleading.

5. Personal Space and Physical Gestures

Autistic individuals may stand closer or farther than expected, or feel uncomfortable with casual touch. What feels friendly to one person may feel intrusive or overwhelming to another—especially for those with sensory sensitivities.

Why differences in social cues happen

Differences in how autistic people interpret social cues aren’t faults—they reflect the natural diversity of human thinking.

Communication is a two-way street, and misunderstandings often happen on both sides.

Researchers now talk about the “double empathy problem,” which highlights that autistic and non-autistic people may struggle to understand each other because they experience the world differently.

As Dr. Damian Milton, an autistic scholar, explains, this mutual disconnect is less about deficits and more about speaking different social languages.

Recognizing that can ease pressure—it’s not that autistic people lack social skills, but that they operate by different rules.

One challenge is the so-called “hidden curriculum”: unwritten social norms most people assume everyone knows.

For autistic individuals, these implicit expectations—like offering guests a drink or not singing in a quiet office—can be invisible unless stated directly.

As one advocate put it, “Allistic people don’t make rules. Instead, they create expectation traps for those of us who can’t ‘read between the lines.’”

This captures the frustration of being judged for missing cues no one actually explained.

Real Experiences: Autistic Perspectives on Social Cues

Autistic individuals often share strikingly similar experiences when it comes to navigating social cues.

These personal stories highlight how unclear expectations and indirect communication can lead to misunderstandings—not due to lack of empathy, but because the rules were never made explicit.

Missing Hints and Indirect Requests

One autistic woman recalled a coworker repeatedly saying, “I wonder if someone should help on the tills…” during a busy shift.

She took it as casual musing and replied, “Maybe,” unaware it was a polite way of asking her to step in.

Only after multiple hints did she realize it was a request. “If she’d just asked me directly,” she said, “I’d have done it right away.”

The Unspoken “Surprise” Rule

Another person described how they accidentally ruined a birthday surprise at work. They were told to meet at a set time to give someone cake but weren’t told it was a surprise.

When the celebration didn’t start, they asked aloud, “Are we still having cake?”—prompting awkward silence.

They later said, “I was just following the plan I was given. No one told me not to say anything.”

Tone, Sarcasm, and Jokes

Sarcasm and playful teasing can be tricky. One commenter admitted, “I often mess up joking because my tone is off or I say something too blunt. I never mean to be mean—it just comes out wrong.”

Others described not realizing they were being teased or laughed at until much later, often leading to confusion or hurt.

Literal Interpretations of Implied Messages

A woman shared that her upstairs neighbor would ask, “I hope I’m not too loud with my dog?” She always reassured him it wasn’t a problem.

Much later, she realized he was likely hinting that her TV was too loud. “I wish people would just say what they mean,” she reflected.

It wasn’t unwillingness to change—just a missed cue in an indirect message.

Navigating Social Cues as an Autistic Person (Tips for Support)

Social interactions can feel confusing when the rules aren’t clearly explained. But with the right support and self-understanding, it’s possible to navigate social cues more comfortably—without masking who you are.

Here are some helpful strategies:

1. Ask for Clarity

If someone’s message feels vague, it’s okay to ask for clarification.

Questions like “Do you want me to help now?” or “Are you suggesting I do that?” can prevent confusion.

Many people appreciate direct communication more than we assume.

2. Be Open About Your Communication Style

Letting others know you prefer clear, literal language can go a long way.

Saying something like, “I sometimes miss hints, so feel free to be direct,” helps build mutual understanding and reduces pressure on both sides.

3. Learn Social Patterns—On Your Terms

Some autistic people find it helpful to learn common social cues intentionally, through videos, books, or support groups.

The goal isn’t to mask, but to gain tools that help you navigate social situations when it feels useful.

4. Use Your Strengths

Written communication, direct conversations, or shared interests may work better for you than small talk or reading body language.

These are valid and valuable ways to connect—lean into what feels most natural.

5. Watch Out for Masking Burnout

Adapting to social norms can be exhausting if it means hiding your true self.

If you find yourself constantly pretending to fit in, take breaks and reassess.

Authenticity matters. Your well-being is more important than meeting every unspoken social expectation.

6. Find Neurodivergent Spaces

Online or in-person communities with other autistic or neurodivergent people can provide relief and connection.

In these spaces, there’s often less pressure to “perform” social behaviors and more understanding of diverse communication styles.

7. Remember: It’s a Two-Way Street

Understanding doesn’t just have to come from you. Friends, family, teachers, and coworkers can also learn to be clearer and more accepting.

When both sides make the effort, social interaction becomes more respectful and inclusive.

Embracing Differences, Not Deficits

Autistic people may navigate social interactions differently, but that doesn’t mean they’re broken or need fixing. These are differences, not deficiencies.

Communication styles vary across individuals, and autistic ways of expressing, connecting, and interpreting the world are equally valid.

In fact, autistic communication often brings strengths—like honesty, deep focus, and sincerity. Many people on the spectrum form meaningful relationships, just through different pathways.

As understanding of neurodiversity grows, so does the realization that there isn’t one “correct” way to be social.

By recognizing and respecting different communication styles, we create a world that’s more inclusive—not just for autistic people, but for everyone.

When both autistic and non-autistic people make space for each other’s needs, social interactions become richer, more authentic, and far more human.