Both autistic people and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) experience repetitive thoughts. Because of this, autism and OCD are often confused—by professionals, individuals, and families alike.

In fact, OCD occurs in 17–37% of autistic youth, and autistic traits appear in many people with OCD.

However, the nature of these thoughts and the feelings behind them can be very different.

By understanding the distinction between autistic rumination and OCD, you can better recognize what you’re dealing with – and find the right strategies to cope.

What Is Autistic Rumination?

Rumination means going over something repeatedly in your mind.

For autistic people, this might involve reliving conversations, fixating on past mistakes, or obsessing over an interest. It often feels like the brain won’t “let go” of a thought.

This mental replay is common in autism due to traits like intense focus, detail-oriented thinking, and a need for predictability.

When things feel unclear or unresolved—like a confusing social situation—the autistic brain may ruminate in an attempt to understand or prevent future distress.

Sometimes this rumination is neutral or enjoyable, especially when focused on a special interest. For instance, someone might spend hours thinking about train schedules or favorite TV shows. Even then, the repetition can become overwhelming.

“I love my special interests but sometimes I wish I could turn my brain off.” — forum user

Autistic rumination is usually ego-syntonic—it feels like a natural part of the person’s thinking style, even if it’s exhausting. It’s not driven by fear of something bad happening but often by a need for clarity or comfort.

What Are OCD Intrusive Thoughts?

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) involves obsessions (unwanted, intrusive thoughts or images) and compulsions (behaviors or mental rituals performed to relieve anxiety).

OCD thoughts are typically ego-dystonic—they feel alien, distressing, and out of sync with the person’s values. Common obsessions include fears of contamination, harming others, or moral wrongdoing.

“OCD is my brain saying if I don’t do this or that, I’ll die—or my family will. It’s like being a hostage to my own mind.” — Forum user

To manage the anxiety, people with OCD perform compulsions, like checking, repeating, or mentally reviewing. These aren’t enjoyable; they’re urgent, distress-driven behaviors aimed at neutralizing fear.

OCD obsessions are rarely based in reality or linked to personal interests. They often involve irrational or catastrophic scenarios.

The compulsions feel necessary to prevent imagined disasters—even if the person logically knows the fear is unfounded.

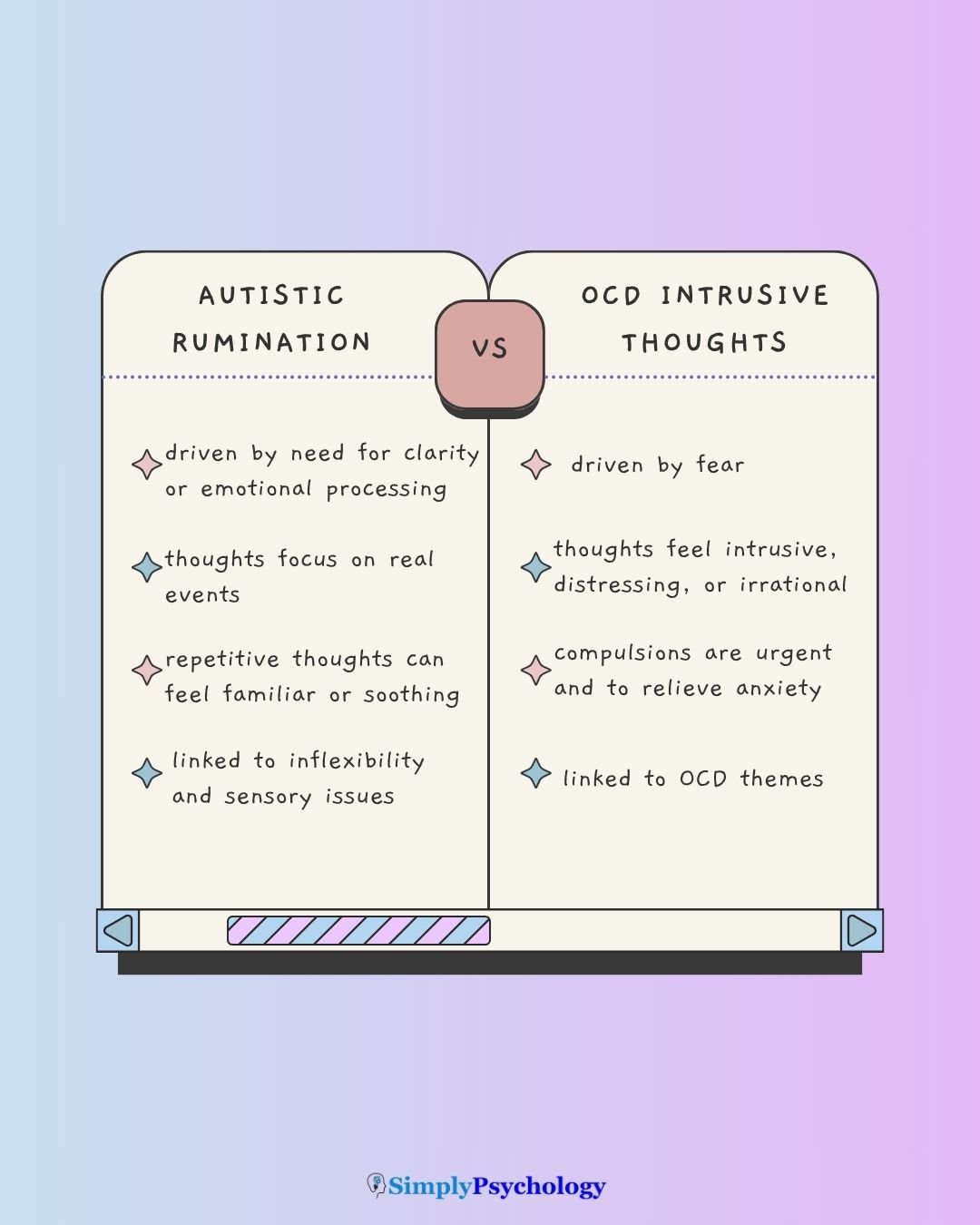

Key Differences Between Autistic Rumination and OCD Intrusive Thoughts

Although both autistic people and those with OCD experience repetitive thoughts, the underlying causes, emotional tone, and goals of these thought patterns are fundamentally different.

Here’s a clearer breakdown:

Content of Thoughts

Autistic rumination often focuses on real-life situations, such as misunderstandings, past mistakes, upcoming changes, or sensory overwhelm.

These thoughts may revolve around social confusion, fear of future disruption, or trying to make sense of past distress.

For example, someone might constantly replay an awkward interaction or worry endlessly about a change in their daily routine.

By contrast, OCD thoughts are usually irrational, intrusive, and fear-based. They often involve imagined catastrophes—like fears of contamination, harming someone, or doing something morally wrong—even when the person knows these fears are unlikely.

Emotional Tone

The emotional quality of the thought is one of the clearest distinctions.

- Autistic rumination can be distressing, especially when it involves negative experiences or uncertainty. However, the distress tends to come from over-analysis, emotional sensitivity, or difficulty disengaging from the thought—not from the belief that something terrible will happen.

- OCD obsessions, on the other hand, are intensely fear-driven. They often provoke immediate anxiety, guilt, or dread. The thoughts are ego-dystonic—meaning they feel alien and upsetting.

Purpose of Repetition

Autistic rumination often serves a processing function. It helps make sense of emotional, social, or sensory experiences, or it may stem from a need for predictability and control.

In OCD, repetition is compulsive—it’s a response to an intrusive thought that feels threatening. The behavior is aimed at neutralizing fear or preventing harm, even if the person knows it’s irrational.

For instance:

- An autistic person may repeatedly think about how to navigate a loud, unfamiliar environment to feel more prepared.

- A person with OCD might wash their hands 20 times to “prevent” getting seriously ill, despite no real evidence of danger.

Fear vs. Need for Understanding

In OCD, fear is central. The person performs rituals or mental checks to avoid imagined disasters. In autism, the repetitive thinking often stems from a need to understand, predict, or regulate rather than avoid harm.

For example, someone with OCD may believe something terrible will happen unless they perform a ritual. Someone autistic may ruminate on how to prevent a meltdown in a sensory-heavy environment—not because of irrational fear, but because of past overwhelm.

Shame and Insight

OCD thoughts are typically accompanied by shame or a strong desire to hide the behavior. People with OCD often feel distressed by their compulsions and know they are irrational.

Autistic rumination is usually ego-syntonic—the thoughts feel like part of who the person is. While the rumination can cause distress, it’s rarely associated with shame unless the person has been criticized or misunderstood by others.

As one autistic writer put it:

“I ruminate because I’m trying to understand something that doesn’t come naturally. It’s not because I believe something awful will happen if I don’t.”

Style of Thinking

Autistic rumination is often logical, detailed, and narrative-based. It may involve replaying events to extract patterns, avoid future confusion, or understand emotional responses.

Many autistic people experience loops of concern—worrying about potential disruptions, not because they’re irrational, but because routine and predictability matter deeply.

OCD thoughts tend to be more magical or extreme—such as “If I don’t repeat this prayer, my family will die.” They may lack grounding in reality and follow a rigid, superstitious logic.

Can Someone Have Both?

Yes. Many autistic individuals also have OCD. In these cases, they may experience both:

- Comforting repetitive thoughts tied to special interests (autism)

- Distressing intrusive thoughts requiring mental rituals (OCD)

Differentiating between the two helps guide treatment and self-understanding. One autistic person explained:

“I don’t mind people knowing I eat the same breakfast every day—that’s comforting. But I hide my OCD… I’m ashamed of those rituals.”

Managing Autistic Rumination

The goal isn’t to eliminate autistic thinking patterns, but to reduce distress when rumination becomes overwhelming.

Helpful strategies:

- Write it out: Journaling or voice notes help externalize thoughts and stop looping.

- Set boundaries: Use a timer to limit ruminating sessions—e.g., 20 minutes, then shift focus.

- Engage in stimming or sensory activities: Humming, walking, or stimming can redirect mental energy.

- Practice grounding: Mindfulness, deep breathing, or sensory exercises can interrupt spirals.

- Target anxiety triggers: Build tolerance to uncertainty through support or therapy.

For many, validation also helps. Learning that perseveration is part of autism—not a flaw—can reduce shame and anxiety.

Managing OCD Obsessions

Because OCD is fear-based, it often requires a different approach. The most effective treatment is CBT with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP).

Self-management tips:

- Name the OCD: Labeling the thought (“That’s OCD talking”) helps create distance.

- Delay compulsions: Wait five minutes before acting; over time, increase the delay.

- Avoid reassurance: It may feel helpful, but it feeds the OCD cycle.

- Accept uncertainty: Try living with 90% certainty instead of seeking absolute reassurance.

- Reduce stress: Sleep, movement, and downtime can lower baseline anxiety.

Still, professional therapy is key. OCD is treatable, and ERP has strong evidence behind it. Medication (like SSRIs) may also help in moderate to severe cases.

When to Seek Support

If repetitive thoughts—of any kind—are interfering with daily life, professional evaluation is important. A psychologist can help determine whether the issue is OCD, autism-related rumination, or both.

For autistic people, therapy adapted to neurodivergent needs (e.g., slower pacing, visual tools, concrete goals) can be helpful. For OCD, ERP tailored to sensory sensitivities can be effective.

Also consider peer support. Online groups for OCD or autism can provide validation, practical tips, and community.

References

Martin, A. F., Jassi, A., Cullen, A. E., Broadbent, M., Downs, J., & Krebs, G. (2020). Co-occurring obsessive–compulsive disorder and autism spectrum disorder in young people: prevalence, clinical characteristics and outcomes. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 29(11), 1603-1611.