Autistic people often experience rumination—repetitive, intrusive thought loops that can resemble anxiety or depression.

From the outside, these thought patterns can look like classic worry or sadness, raising an important question: Are autistic individuals being misdiagnosed with anxiety or depression when the root issue is actually autistic rumination?

One autistic person described it this way:

“I will ruminate on social interactions after the fact, but it doesn’t feel like it springs from anxiety. It feels more like compulsory processing.”

Rather than stemming from fear or hopelessness, these loops can reflect an autistic mind trying to process, understand, or gain clarity.

Yet, to clinicians unfamiliar with autistic thinking, this may appear as anxiety or depressive rumination.

Understanding Rumination in Autism

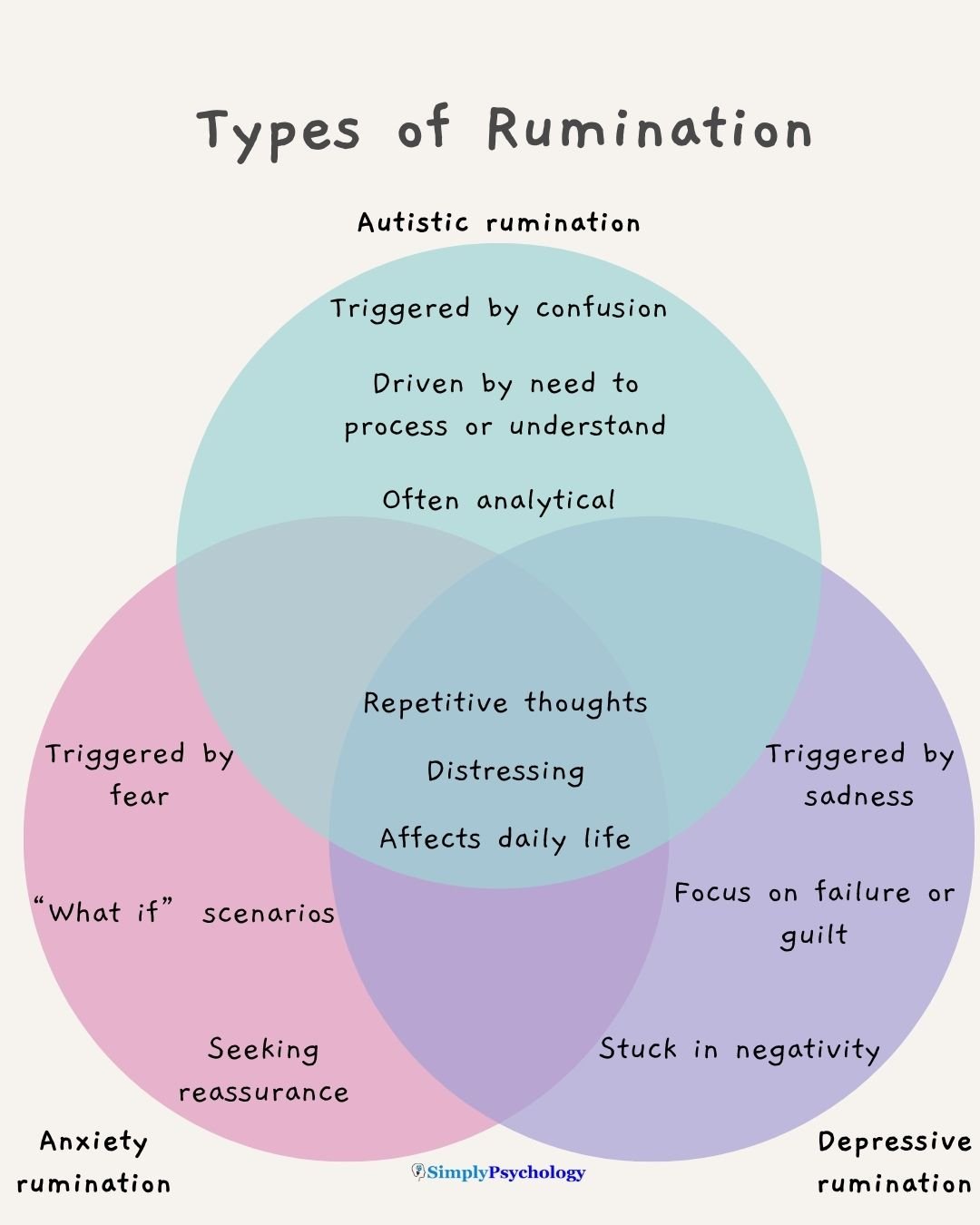

Rumination involves persistent, repetitive thinking, often linked to distress. In anxiety, this might mean obsessing over future threats. In depression, it might involve dwelling on regrets or inadequacy. But autistic rumination can differ in meaningful ways:

Processing Overload

Autistic people may struggle to process emotionally intense moments in real time. Their minds often revisit events later, breaking them down in detail.

As one person explained, it feels like “compulsory processing”—an automatic need to make sense of something too overwhelming in the moment.

Emotion and Justice

Many autistic individuals replay moments that felt unjust or confusing. One person wrote:

“I find myself replaying scenarios, wondering, ‘Did I communicate how unjust this situation was?’ or trying to understand why someone would do something so hurtful.”

This suggests a drive for resolution, not just emotional release.

“Loops of Concern”

Autistic advocate Sonny Hallett describes these spirals as “loops of concern,” often rooted in uncertainty:

“Often, these loops are centred around something we are not sure about: was that friend angry? Did I leave my phone on the bus or at home? Did I misinterpret or accidentally break a rule?”

While these thought loops can be distressing, they don’t always arise from fear or sadness. An autistic person may look withdrawn or anxious, but internally, they might be carefully analyzing a past interaction—rather than anticipating disaster or feeling hopeless. This difference can be subtle, but it matters.

Autistic vs. Anxiety/Depression Rumination

Though all forms of rumination involve repetitive thoughts, their content, motivation, and purpose often diverge:

Focus of Thoughts

- In social anxiety, people fixate on embarrassment or judgment—e.g., “I sounded stupid.”

- In autism, rumination focuses on decoding social rules—e.g., “What did that gesture mean?”

- In depression, the thoughts tend to be self-critical or hopeless—e.g., “Nothing ever works out for me.”

Autistic rumination often tries to “solve the puzzle” of what happened, rather than spiraling into self-blame.

Emotional Trigger

- Anxiety-driven rumination starts with fear—worrying about the future or what might go wrong.

- Depression-related rumination stems from sadness, guilt, or despair.

- Autistic rumination may begin with confusion or a need to understand. As one autistic person said, “It doesn’t feel like it springs from anxiety.” They’re not always afraid—just unsettled by something unresolved.

Goal of Rumination

- In anxiety, the goal is often to prevent danger—ruminating to avoid missing something important.

- In depression, there may be no goal—just a mind stuck in negativity.

- Autistic rumination often aims to process or resolve—replaying events to analyze, mentally rehearse responses, or retain the emotional significance of a situation.

As one person put it:

“I replay situations so I don’t forget why I’m mad. I rehearse the pending confrontation… but it never happens, and I waste all my energy preparing for imaginary situations.”

These thought patterns can be analytical rather than anxious—but they may look similar on the surface.

Why Misdiagnoses Happen

Autistic rumination is frequently mistaken for anxiety or depression due to overlapping symptoms and a lack of autism-informed assessment. Misdiagnosis can happen in two ways:

- Autism is misinterpreted as a mood or anxiety disorder.

- Autism is missed entirely, and only the anxiety or depression is diagnosed.

It is also very possible that someone has an anxiety or mood disorder alongside autism.

Here’s why:

Overlapping Signs

Autism, anxiety, and depression can all involve flat affect, social withdrawal, or difficulty communicating emotion.

An autistic person might have a neutral facial expression or monotone voice—not because they’re depressed, but due to how they express themselves. As psychologist Dr. Katherine Gotham explains:

“If someone seems less interested in social things, is it because they have autism, or because they’re a person with autism who’s depressed?”

It requires context to tell the difference.

Masking and Internalization

Autistic individuals, especially women, people of color, or those socialized to blend in, often camouflage their traits.

They may appear mildly anxious or depressed, while their underlying autism goes unrecognized. As one psychologist notes:

“Many autistic people I work with were initially diagnosed with social anxiety while their autism was missed.”

Their rumination may be seen as anxiety-driven, when it’s actually linked to autistic processing or burnout.

Secondary Conditions

Many autistic people do experience real anxiety or depression. But sometimes, clinicians only see those conditions and miss the autism underneath.

For example, an autistic person in burnout—emotionally exhausted, withdrawn, overwhelmed—may look clinically depressed.

Yet typical treatments (e.g., antidepressants) may not help because the root issue is autistic burnout, not a serotonin imbalance.

Misinterpretation of Behavior

Autism And Eye Contact: Why Is It So Difficult?Clinicians unfamiliar with autism may misread signs like lack of eye contact or repetitive speech.

These behaviors may be interpreted as sadness or anxiety when they are actually normal for that individual. One person may perseverate on a topic to self-soothe, not because they’re anxious.

These misunderstandings can lead to years of misdiagnosis. One autistic adult shared:

“I was diagnosed with major depression and bipolar 2… but over time I realized the sensory stuff, low stress tolerance, and other patterns fit autism. I’m not bipolar. I think I’m autistic.”

Their story echoes many others who were treated for mood disorders before learning they were neurodivergent.

Getting the Right Diagnosis and Support

Accurate diagnosis is essential. If autistic rumination is mistaken for anxiety or depression alone, treatment may only address part of the issue.

Therapy or medication may help reduce distress—but not if the person’s thinking style or sensory needs remain unsupported.

Here’s how to move toward a clearer understanding:

1. Seek a Neurodiversity-Affirming Evaluation

Find a clinician experienced with autism—especially in adults or those who mask. A full assessment will explore life history, sensory sensitivities, communication style, and thinking patterns.

This helps distinguish what’s truly anxiety/depression from what’s autistic processing.

2. Differentiate Burnout from Depression

If you feel emotionally shut down, exhausted, and disconnected, consider both depression and autistic burnout.

Though the symptoms overlap, burnout stems from prolonged masking, sensory overload, or social strain.

It may require different support—like reducing demands, increasing sensory comfort, and connecting with other autistic people.

Depression might call for therapy or medication, but both conditions can coexist and need tailored care.

3. Try Tailored Coping Strategies

Regardless of diagnosis, heavy rumination benefits from practical tools. Autistic individuals often find writing helpful—externalizing thoughts can ease mental loops.

One person shared that journaling “helps break the loop a little,” while another said it “sort of helps my brain check it off the list.”

Other strategies:

- Symbolic rituals (e.g., burning or shredding the paper after writing)

- Distraction (e.g., walking, doing dishes, engaging in a hobby)

- Grounding techniques (e.g., mindfulness, breathing, sensory activities)

4. Talk to Your Provider

If you have an anxiety or depression diagnosis but feel it doesn’t fully explain your experience, bring it up.

Try saying: “I tend to fixate on things—not just from anxiety, but because I need to understand. Could this be autism?”

A thoughtful clinician will take this seriously or refer you to someone who can help. You’re the expert on your own mind—and an open conversation can be a key step toward clarity.

Some experts now recommend screening for autism when anxiety or depression proves resistant to standard treatment. As awareness grows, such misdiagnoses may become less common.