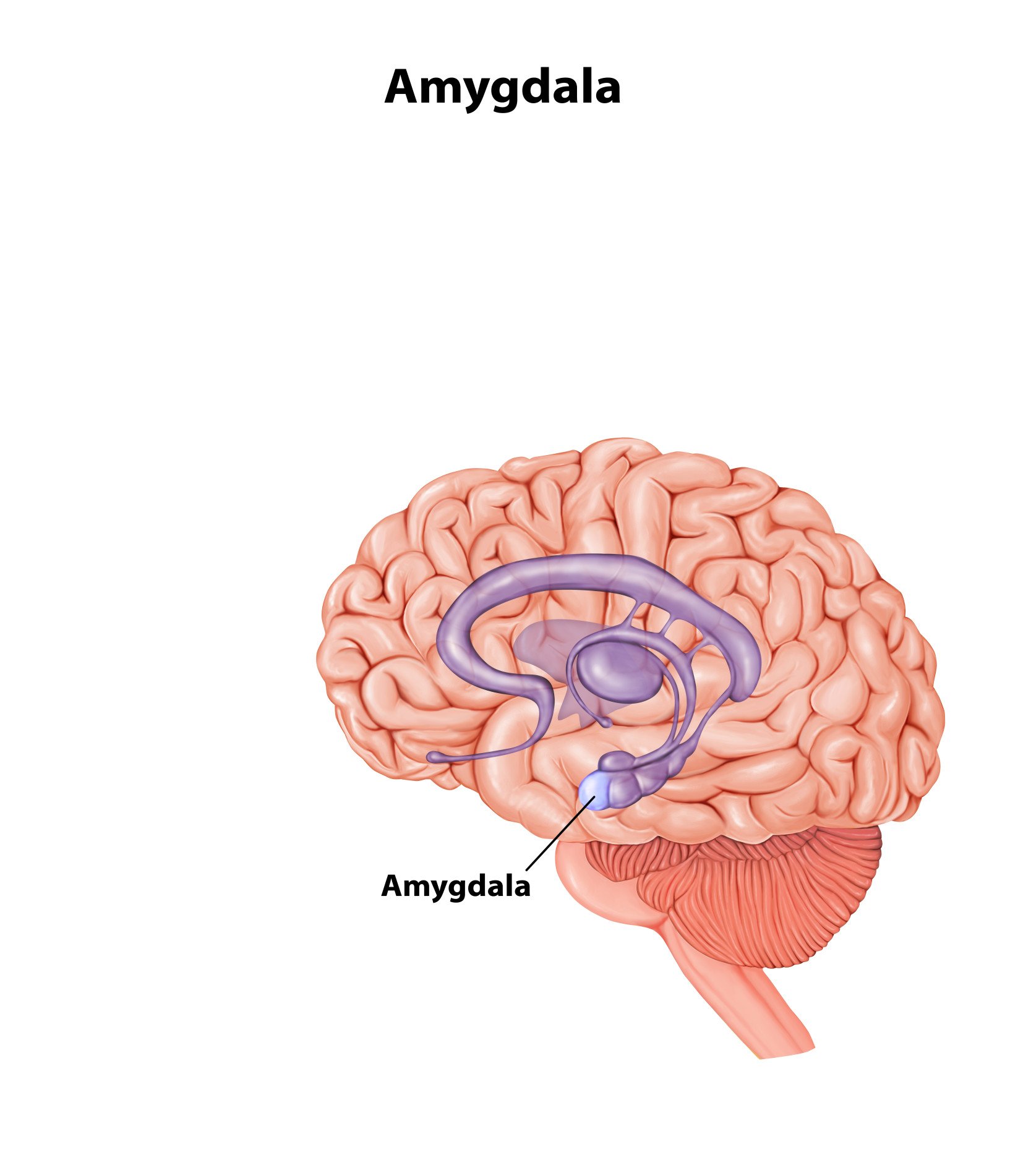

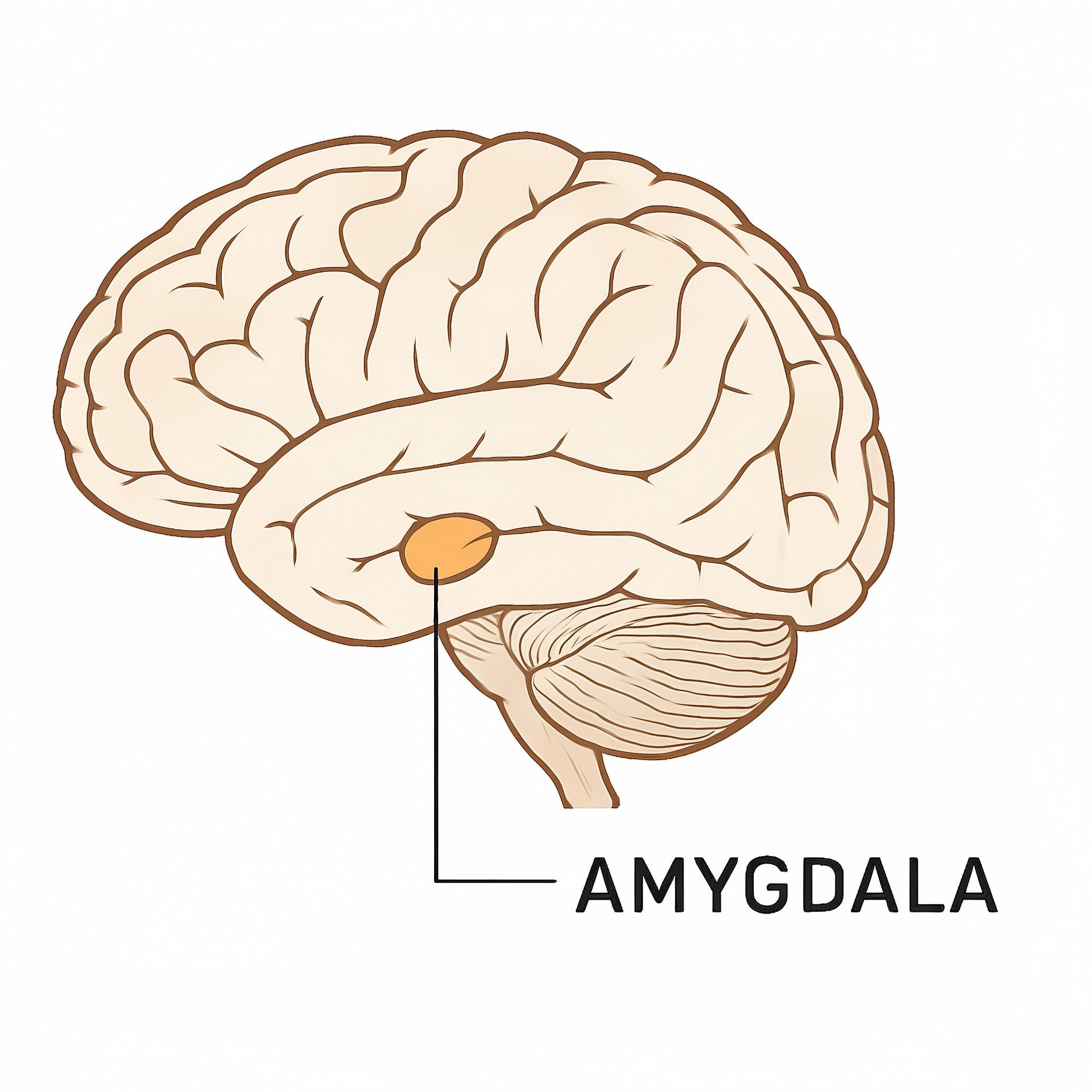

The amygdala is an almond-shaped cluster of neurons located deep within the temporal lobe of the brain.

As a critical component of the limbic system, the amygdala acts as a central hub for sensory integration and emotional processing.

Described as the brain’s emotional computer, the amygdala evaluates sensory information for emotional significance, specifically potential threats, and coordinates the appropriate responses.

It facilitates the encoding of long-term memories by “tagging” them with emotional weight.

This ensures that biologically significant events – such as those involving fear or reward – are prioritized for storage in the hippocampus.

Where is the amygdala located?

The amygdala consists of two almond-shaped clusters tucked deep inside the temporal lobes (the area of the brain near your temples).

You have one on each side, sitting roughly level with your eyes.

If you were to point a finger into your ear and another finger straight through your eye, the point where those two lines would meet inside your head is roughly where the amygdala sits.

It is a core part of the limbic system, which is the brain’s “emotional headquarters.” Its specific location is key to how it functions:

- Next to the Hippocampus: Positioned right in front of the brain’s memory center (the hippocampus), it allows the amygdala to “label” memories with strong emotions like fear or joy.

- Near the Hypothalamus: Being close to this regulatory center allows the amygdala to quickly trigger physical reactions, like a racing heart, when it senses danger.

- Deep and Protected: Because it is located beneath the outer layers of the brain, it can process survival instincts much faster than our conscious, “thinking” brain.

What Does The Amygdala do?

The amygdala is essential for processing emotional reactions and attaching emotional significance to experiences, playing a central role in various aspects of behavior and cognition.

1. Emotional Regulation

The amygdala is the primary hub for processing emotions like fear, aggression, and happiness.

It is essential for fear conditioning, a form of associative learning where a neutral stimulus (like a sound) is linked to an aversive event.

This creates a conditioned response, allowing the organism to anticipate danger.

Dual-Path Processing (The LeDoux Pathways)

Research by Joseph LeDoux indicates the amygdala processes fear stimuli through two pathways: a “fast path” directly from the thalamus for immediate reaction, and a “slow path” through the cortex for detailed processing

The amygdala processes threats via two distinct circuits:

- Fast Path (Subcortical): A rapid, direct pathway from the thalamus to the amygdala. It bypasses the conscious mind for nearly instantaneous “fight-or-flight” activation.

- Slow Path (Cortical): A slower pathway where information travels through the sensory cortex for detailed analysis. This allows the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) to “brake” or dampen the amygdala’s response if the threat is deemed false.

2. Memory Consolidation

The amygdala enhances memory consolidation by working with the hippocampus.

Working alongside the hippocampus, the amygdala attaches “emotional weight” to memories.

This ensures that high-stakes events (trauma or joy) are encoded more vividly.

Emotional arousal triggers a “tagging” mechanism using stress hormones, which strengthens the synapses involved in that specific memory. This is the biological basis for classical fear conditioning

Emotional memories, particularly fear-based, are thought to be stored within the synapses of neurons in the amygdala.

On a cellular level, these memories are likely stored through changes in synaptic plasticity within amygdala neural circuits.

3. Modulation of Aggression

The amygdala acts as a biological “trigger” for aggressive behavior.

Research shows that stimulating this region increases hostile responses, while damage (lesions) leads to a marked decrease in aggression, highlighting its role in social survival instincts.

4. The Stress Response (Fight or Flight)

The amygdala is sensitive to both acute and chronic stressors.

When a threat is detected, the amygdala signals the hypothalamus, which activates the sympathetic nervous system.

This results in the physiological fight or flight respons: increased heart rate, adrenaline release, and heightened alertness.

Exposure to stress affects neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity within the amygdala, indicating its pivotal role in processing stress responses.

5. Social & Addictive Behaviors

The amygdala also influences social interactions and relationships.

It modulates social behaviors through bidirectional connections with the hippocampus.

The amygdala helps interpret facial expressions and social cues. Interestingly, neuroimaging shows that it also plays a role in culturally learned social biases

- Social Networks: Larger amygdala volume is positively correlated with more complex social networks, suggesting it helps process social cues and bond formation.

- Addiction: The basolateral amygdala links drug-related environmental cues with stress responses, often driving the “craving” cycle and increasing the risk of relapse.

6. Clinical Significance & Mental Health

Dysfunction in the amygdala is a hallmark of several conditions:

- Hyperactivity: Hypervigilance, panic attacks, and an overactive fight-or-flight response. Linked to PTSD and Social Anxiety (over-responsiveness to perceived threats).

- Volume Changes: Reduced amygdala volume (up to 15-20% in some studies) has been observed in patients with chronic Bipolar Disorder or long-term Depression.

- Hyporeactivity: In individuals with psychopathic tendencies, a lack of amygdala activation often correlates with an inability to learn from punishment (impaired fear conditioning).

- Structural Changes: Persistent negative emotional states due to a lack of “top-down” regulation from the Prefrontal Cortex.

7. Respiratory Control

Recent evidence suggests the amygdala influences the medulla oblongata to regulate breathing.

During seizures, over-activation of the amygdala can cause apnea (temporary cessation of breathing), revealing its role in involuntary survival functions.

Amygdala Hijack

Amygdala hijack refers to an immediate, overwhelming emotional response that bypasses the brain’s rational processing centers.

This occurs when the amygdala, the brain’s emotional center, reacts to a stimulus before the cerebral cortex (the thinking brain) has a chance to evaluate it.

Essentially, the amygdala overrides the frontal lobes to hijack stress response control.

The Neural Mechanism: Two Pathways to Emotion

Research by neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux identifies two distinct pathways through which the brain processes fear and emotion.

An amygdala hijack effectively represents the dominance of the “fast path” over the “slow path”:

- The Fast Path (The Hijack): Sensory information travels directly from the thalamus to the amygdala. This transmission is extremely rapid and allows for an almost instantaneous response to a threat. Because this path bypasses the cortex, the emotional reaction occurs separately from, or prior to, cognitive interpretation.

- The Slow Path (The Rational Response): Information travels through the sensory cortex for detailed analysis. This allows the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) to “brake” or dampen the amygdala’s response if the threat is deemed false.

Vulnerability Factors

Certain conditions can make the brain more susceptible to this hijacking by increasing amygdala sensitivity or decreasing cortical control:

- Sleep Deprivation: Lack of sleep causes the amygdala to become more sensitive and overreact to stimuli. Imaging studies show the amygdala reacts more strongly to fearful faces in sleep-deprived individuals, which helps explain irritability and “crankiness” when tired.

- Stress and Trauma: Exposure to chronic stress or trauma can sensitize the brain’s response systems, making them over-responsive to stress. In conditions like depression, the amygdala shows elevated activity even when stimuli are presented outside of conscious awareness.

Amygdala’s Connections and Neuronal Circuits

The amygdala is not a uniform mass; it is a complex, modular structure consisting of two nuclei (one in each hemisphere) divided into functionally distinct groups.

The amygdala is modular, with different “subnuclei” handling specific stages of information processing:

1. Functional Anatomy: The Three Subnuclei Groups

The amygdala’s internal architecture allows it to specialize in different types of biological signaling:

- The Basolateral Group: * Location: Below and to the side.

- Function: This is the primary “input” hub. It has extensive connections with the cerebral cortex and prefrontal cortex.

- Role: It links complex sensory stimuli with emotional significance and works with the hippocampus to form emotional memories.

- The Central and Anterior Group:

- Location: The front and center.

- Function: The primary “output” hub. It connects to the brainstem and hypothalamus.

- Role: It initiates the autonomic nervous system response (e.g., increased heart rate and adrenaline release) when a threat is detected.

- The Medial Group: * Location: The middle.

- Function: Linked heavily to the olfactory bulb (smell).

- Role: Processes scents to influence social and reproductive behaviors, illustrating the evolutionary link between smell and emotion.

2. The Connectivity Map: Integrating the System

To coordinate survival, the amygdala acts as a “relay station” between different parts of the Central Nervous System (CNS):

When writing about the amygdala, students should focus on the bidirectional nature of these connections. This explains how the brain “self-regulates” – the amygdala alerts the cortex to a threat, and the cortex eventually signals the amygdala to stand down.

A. Sensory Input (The Intake)

- Source: Sensory thalamus and sensory cortices (visual, auditory, somatosensory).

- Result: Provides the amygdala with raw data about the environment (e.g., seeing a snake or hearing a loud bang).

B. Regulation and Decision-Making (The Filter)

- Connection: Bidirectional link with the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC).

- Result: Integrates “cold” logic with “hot” emotion, allowing the PFC to dampen amygdala activity once a threat is resolved.

C. Memory and Learning (The Record)

- Connection: Bidirectional link with the Hippocampus.

- Result: Ensures that emotionally significant events are prioritized for long-term storage, helping the organism learn to avoid future dangers.

D. Physiological Output (The Action)

- Connection: Output to the Hypothalamus and Brainstem.

- Result: Activates the sympathetic nervous system for the fight-or-flight response.

E. Reward and Motivation (The Drive)

- Connection: Output to the Nucleus Accumbens and Ventral Striatum.

- Result: Involved in reward-seeking behavior and addiction, linking positive emotions to specific actions.

What Happens If The Amygdala Is Damaged?

Damage to the amygdala primarily results in profound deficits in emotional processing, particularly regarding fear, aggression, and the ability to attach emotional significance to memories.

Because the amygdala acts as a central hub for integrating sensory information with emotional and autonomic responses, its destruction disrupts survival instincts and social behavior.

1. Disruption of Emotional Processing

The most significant impact of amygdala damage is the blunting of fear and aggression.

-

Loss of Fear Conditioning: Since the basolateral complex is the site of associative learning, damage here prevents an organism from linking a neutral stimulus (like a warning sound) with an aversive event (like a shock).

-

Deficits in Social Perception: Humans with amygdala damage often cannot recognize fear in the facial expressions of others. They lose the “emotional instinct” required to navigate social hierarchies.

-

The “Taming” Effect: In animal studies, damage to the amygdala can turn naturally aggressive or wild animals into docile ones, as they lose the ability to perceive a threat or mount a defensive response.

2. Klüver–Bucy Syndrome

A landmark area of study in neurobiology is Klüver–Bucy Syndrome, which occurs when the temporal lobes (including the amygdala) are removed or damaged.

It is characterized by:

-

Docility: A complete lack of fear or anger.

-

Hyperphagia: An indiscriminate drive to eat, often attempting to consume non-food objects.

-

Hyperorality: A tendency to examine objects with the mouth.

-

Hypersexuality: An excessive and indiscriminate sex drive.

3. Impact on Memory: Loss of “Emotional Boost”

While the hippocampus handles the “what, where, and when” of a memory, the amygdala handles the “emotional intensity.”

-

Memory Consolidation: Normally, stress hormones (like adrenaline) activate the amygdala to strengthen memory storage in the hippocampus.

-

The Result of Damage: Patients with bilateral amygdala damage can remember facts about a traumatic event but do not experience the vivid, “highlighted” memory that healthy individuals do.

Case Study: Henry Molaison (H.M.) H.M. had his hippocampus and amygdala removed to treat epilepsy. This resulted in anterograde amnesia (the inability to form new facts) but also a striking inability to recognize the emotional significance of new people or experiences.

How to Soothe Your Amygdala

Soothing the amygdala is biologically defined as re-engaging the Cortical (Slow) Path.

This involves inhibiting the amygdala’s output by strengthening the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) and shifting the Autonomic Nervous System from a Sympathetic (Fight-or-Flight) state to a Parasympathetic (Rest-and-Digest) state.

Calming your amygdala, the brain’s epicenter for emotions such as fear and anxiety, involves a combination of mental health strategies and lifestyle adjustments.

Practical Techniques to Ease Panic

-

- Breathing Exercises: Practice deep breathing to regulate your nervous system. Techniques like the 4-7-8 breathing method can be particularly effective during stressful moments.

-

- Grounding Exercises: Use grounding techniques, such as focusing on your five senses, to anchor yourself in the present and diminish overwhelming emotions.

- Affect Labeling: Simply naming an emotion (“I feel anxious”) creates a measurable change in brain activity. This process engages the prefrontal cortex, helping to dampen the emotional response in a manner similar to more complex strategies like cognitive reappraisal.

Stress and Anxiety Management

-

- Adopt a Mindful Practice: Meditation and yoga are excellent for reducing stress levels and relaxing your amygdala. Apps like Headspace or Calm offer guided practices to get you started.

-

- Stay Active: Regular physical activity releases endorphins, which naturally combat anxiety. Whether it’s a brisk walk or a heart-pumping workout, integrate movement into your daily routine.

-

- Pursue Hobbies: Engage in activities you enjoy, whether it’s painting, gardening, or playing an instrument. Hobbies provide a productive distraction from anxiety and can be an outlet for expression.

- Social Support: The presence of a supportive person can directly affect brain processing; for instance, holding someone’s hand can reduce the activation of stress-related brain areas.

Titration: Moving In and Out of Emotion

Trying to suppress the amygdala’s response entirely is often counterproductive. A more effective approach is titration, or dosing the emotional experience.

In chemistry, titration is the slow addition of one solution to another to reach a reaction point without overshooting.

In neurobiology, it refers to “dosing” a stressful memory or emotion so the amygdala stays within its “Window of Tolerance.”

1. Pendulation: Managing Neural Arousal

Pendulation is the process of swinging the focus between a “resourced” state (feeling safe/calm) and a “stressed” state (the emotional memory).

-

The Mechanism: By moving “in and out” of the stress response, you prevent the amygdala from reaching the threshold of a hijack.

-

The Goal: This allows the Prefrontal Cortex to stay “online” and continue processing the information, rather than being shut down by an overwhelming fear signal.

2. The Failure of Suppression

Trying to “block” or “ignore” an emotion is often counterproductive.

-

Rebound Effect: Suppression requires high levels of metabolic energy from the Prefrontal Cortex. When the PFC tires, the amygdala often reacts with even greater intensity (hyperactivity).

-

Avoidance Learning: Avoiding a thought reinforces the amygdala’s belief that the thought is a genuine threat, strengthening the synaptic pathways of fear.

3. Acceptance and Habituation

Acceptance is a biological strategy to induce habituation – the diminishing of a physiological response to a frequently repeated stimulus.

-

Adaptive Processing: Facing a negative emotion in small, manageable amounts (e.g., one minute) allows the brain to realize the “threat” does not result in actual physical harm.

-

Synaptic Changes: Over time, this “exposure” weakens the excitatory connections between the thalamus and the amygdala, effectively “de-sensitizing” the alarm system.

References

Arehart-Treichel, J. (2014). Changes in Children’s Amygdala Seen After Anxiety Treatment.

Bickart, K. C., Wright, C. I., Dautoff, R. J., Dickerson, B. C., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). Amygdala volume and social network size in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 163-164.

Blumberg, H., Kaufman, J., & Martin, A. (2005). Amygdala and Hippocampal Volumes in Adolescents and Adults With Bipolar Disorder. Year Book of Psychiatry & Applied Mental Health, 2005, 31-32.

Carlson, N. R. (2012). Physiology of behavior. Pearson Higher Ed.Cheng, H., & Liu, J. (2020). Alterations in Amygdala connectivity in internet Addiction Disorder. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-10.

Correll, C. M., Rosenkranz, J. A., & Grace, A. A. (2005). Chronic cold stress alters prefrontal cortical modulation of amygdala neuronal activity in rats. Biological Psychiatry, 58(5), 382-391.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Schuster.

LeDoux, J. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron, 73(4), 653-676.

Felix-Ortiz, A. C., & Tye, K. M. (2014). Amygdala inputs to the ventral hippocampus bidirectionally modulate social behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(2), 586-595.

Harmata, G. I., Rhone, A. E., Kovach, C. K., Kumar, S., Mowla, M. R., Sainju, R. K., … & Dlouhy, B. J. (2023). Failure to breathe persists without air hunger or alarm following amygdala seizures. JCI insight, 8(3).

Kiehl, K. A. (2006). A cognitive neuroscience perspective on psychopathy: Evidence for paralimbic system dysfunction. Psychiatry Research, 142(2-3), 107-128.

LeDoux, J. E. (2020). Thoughtful feelings. Current Biology, 30(11), R619-R623.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (1998). Methodological advances and developments in the assessment of psychopathy. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 36, 99–125.

Maren, S. (2001). Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annual review of neuroscience, 24(1), 897-931.

Phan, K. L., Fitzgerald, D. A., Nathan, P. J., & Tancer, M. E. (2006). Association between amygdala hyperactivity to harsh faces and severity of social anxiety in generalized social phobia. Biological Psychiatry, 59(5), 424-429.

Salzman, C. Daniel (2019, February 27). Amygdala. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/amygdala

Sethi, A., McCrory, E., Puetz, V., Hoffmann, F., Knodt, A. R., Radtke, S. R., … & Viding, E. (2018). Primary and secondary variants of psychopathy in a volunteer sample are associated with different neurocognitive mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(12), 1013-1021.

Sheline, Y. I., Barch, D. M., Donnelly, J. M., Ollinger, J. M., Snyder, A. Z., & Mintun, M. A. (2001). Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biological Psychiatry, 50(9), 651-658.

Swaab, D. F. (2008). Sexual orientation and its basis in brain structure and function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(30), 10273-10274.

Tang, W., Kochubey, O., Kintscher, M., & Schneggenburger, R. (2020). A VTA to basal amygdala dopamine projection contributes to signal salient somatosensory events during fear learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 40(20), 3969-3980.

Vouimba, R. M., Yaniv, D., Diamond, D., & Richter‐Levin, G. (2004). Effects of inescapable stress on LTP in the amygdala versus the dentate gyrus of freely behaving rats. European Journal of Neuroscience, 19(7), 1887-1894.

Wang, X. Y., Zhao, M., Ghitza, U. E., Li, Y. Q., & Lu, L. (2008). Stress impairs reconsolidation of drug memory via glucocorticoid receptors in the basolateral amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(21), 5602-5610.

Zheng, G., Zhou, Y., Zhou, J., Liang, S., Li, X., Xu, C., Xie, G., & Liang, J. (2023). Abnormalities of the Amygdala in schizophrenia: a real world study. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 1-9.

Further Reading