Have you ever felt like your brain was a computer trying to download a massive file, only for the whole system to crash? For many autistic individuals, this isn’t just a metaphor—it is the daily reality of a meltdown.

Unlike a “tantrum,” which is often a choice to get a specific result, an autistic meltdown is an involuntary “crisis experience.”

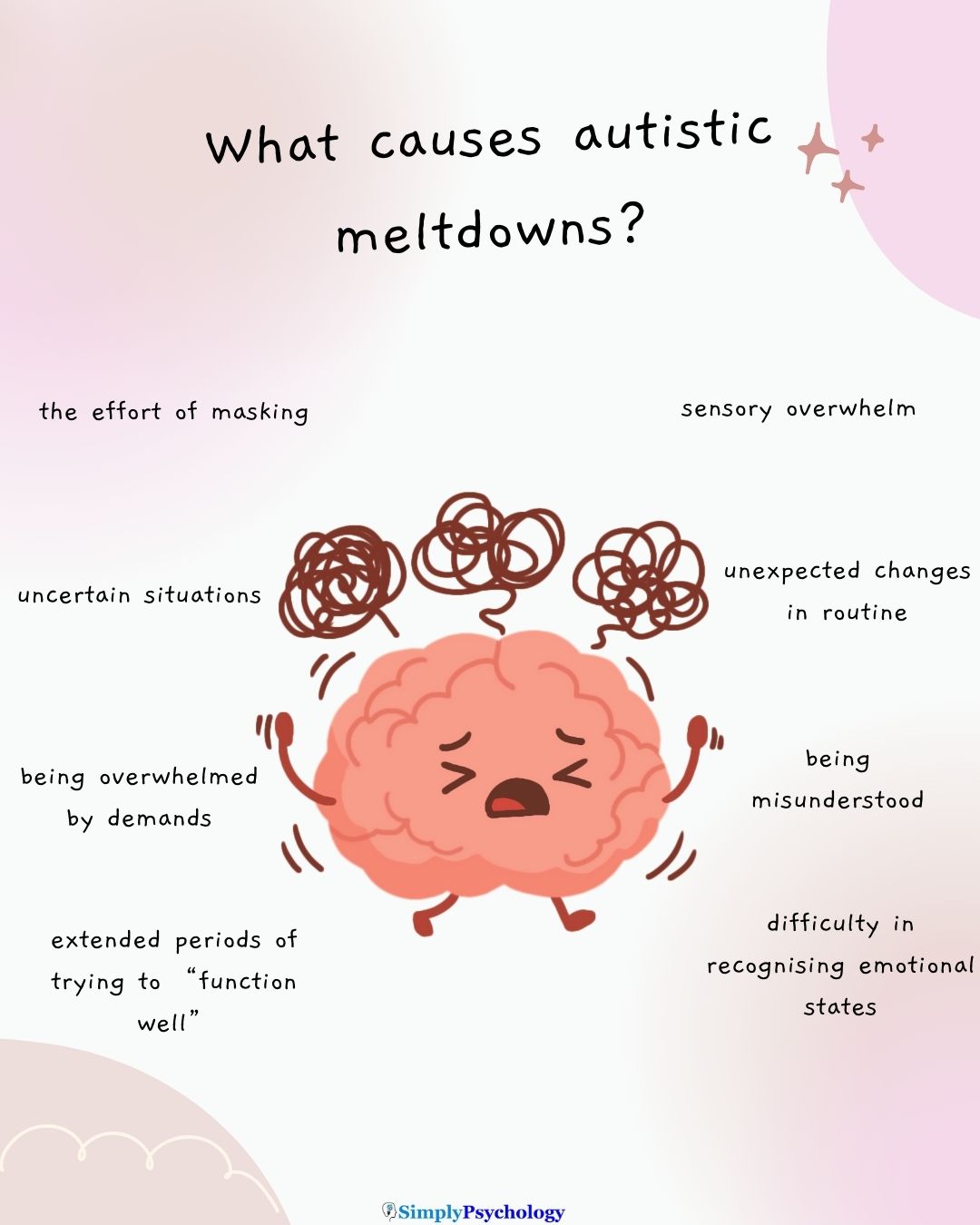

According to leading researchers like Dr. Felicity Sedgewick, Dr. Francesca Happé, and Dr. Amy Pearson, these episodes are biological responses to a world that simply asks too much of an autistic person’s processing power.

If you or a loved one has ever felt “inconsolable” after a minor change or a loud day, you aren’t “being difficult.” You are experiencing a neurological overload.

This guide breaks down the expert-backed reasons why meltdowns happen and how we can better understand the “invisible” pressure that causes them.

A Crisis Experience, Not a Behavioral Problem

The most important thing to understand is that a meltdown is not a “choice.” Dr. Felicity Sedgewick emphasizes that meltdowns are involuntary “crisis experiences.” They happen when internal and external demands exceed a person’s ability to cope.

While a tantrum usually stops once a child gets what they want, a meltdown is a complete loss of control. Dr. Francesca Happé describes these moments as “overloads.”

The person might become tearful, angry, or distressed, but they are not “acting out” to be manipulative. They are simply trying to survive a neurological storm.

The Sensory “Flood” and Brain Wiring

Why does a flickering light or a noisy supermarket cause such distress? Dr. Happé’s research shows that many autistic people experience an “assault on the senses.”

Most people’s brains have “hacks” to filter out background noise, like the hum of a fridge. However, the autistic brain often fails to “habituate,” or get used to, these sounds. As a result:

- The world stays loud: Every sound remains as intense as the first time you heard it.

- The “Unzipped File” Analogy: One expert compares it to a computer. A neurotypical brain receives “zipped” or compressed data. The autistic brain receives raw, “unzipped” files for everything at once.

- System Overclocking: Eventually, the “processor” overheats and crashes.

Dr. Amy Pearson notes that even simple things like a loud bus or a bright store can lead to a “daily burnout.” For some, the flickering of a fluorescent light is physically painful, leading to a build-up of pressure that eventually “bursts.”

The Hidden Cost of “Masking”

Many autistic people spend their day “masking”—suppressing their natural traits to fit in. This might mean forcing eye contact or pretending to be okay with loud noises.

Dr. Amy Pearson and Dr. Sedgewick link this directly to meltdowns.

- The “School vs. Home” Effect: Children often “hold it together” at school to feel safe. Once they return home, the “mask” drops, and they may have a massive explosion of emotion.

- The Boiling Pan: Pearson uses the metaphor of a pan on a stove. Masking keeps the person “on simmer” all day. By the time they get home, a tiny trigger (like a minor noise) causes the pan to boil over.

- Chronic Exhaustion: Research suggests masking is as mentally taxing as solving complex math equations in your head for 24 hours straight.

“Zero to a Hundred”: Emotional Blind Spots

Did you know that about 50% of autistic people experience alexithymia? This is a difficulty in identifying your own emotions. According to Dr. Amy Pearson, this plays a huge role in meltdowns.

Because a person might not recognize they are getting stressed until it’s too late, they don’t have a “dimmer switch” for their feelings.

They often go from zero (feeling calm) to one hundred (a full meltdown) with no warning. They aren’t ignoring their stress; their brain simply isn’t “reporting” the stress until the system is already failing.

The Difference Between Meltdowns and Shutdowns

It is also vital to recognize that not every overload looks “explosive.” Dr. Happé distinguishes between meltdowns and shutdowns:

- Meltdowns: Externalized distress. This can involve shouting, crying, or physical movements. Some describe it as a “ride of destruction” where they feel like a passenger.

- Shutdowns: Internalized distress. The person may go very quiet, withdraw, or lose the ability to speak. This is often called “inertia,” where the person physically cannot generate the energy to interact.

Both are valid responses to the same types of overwhelm and require empathy rather than punishment.

How to Create a Personal “Sensory Audit” Checklist

Identifying triggers before they lead to a “boil over” is one of the most effective ways to manage the cumulative stress that causes meltdowns.

Below is a structured checklist based on the research of Dr. Francesca Happé and Dr. Amy Pearson to help you or a loved one map out sensory and cognitive “energy drains.”

1. The Auditory Audit (Sound)

- Background Hum: Are there appliances (fridge, AC, computer fans) that I can hear but others don’t?

- Sudden Sharp Noises: Do unexpected sounds like sirens, barking dogs, or doorbells cause a “jolt” of anxiety?

- Layered Sound: Is it difficult to follow a conversation when there is background music or multiple people talking?

- The “Habituation” Check: Do I find that I never get used to a repetitive sound, no matter how long it lasts?

2. The Visual Audit (Sight)

- Lighting: Are fluorescent lights flickering or “too white”? (Often described as an “assault on the senses”).

- Clutter: Does a messy room or busy wallpaper feel like “visual noise” that makes it hard to think?

- Motion: Do moving crowds or fast-paced videos leave me feeling dizzy or exhausted?

3. The Cognitive & Social Audit (Masking)

- Social “Performing”: How many hours today did I spend “performing” neurotypical behaviors (eye contact, small talk)?

- Predictive Errors: Have there been any sudden changes to my route, schedule, or plans today?

- Communication Load: Have I been forced to use verbal speech during a time when I felt “on simmer”?

Your Weekly “Decompression” Strategy

According to Dr. Felicity Sedgewick, meltdowns often happen when we lack a “safe environment to decompress.” Use these steps to build a recovery routine:

- The 30-Minute “No-Mask” Window: Immediately after school or work, spend 30 minutes in a low-sensory environment. No talking, no bright lights, and no expectations.

- Sensory Diet Integration: Proactively use “stimming” (rocking, fidgeting, humming) throughout the day. Remember: Suppressing stims is like closing a pressure valve; eventually, the system will burst.

- The “Alexithymia” Body Scan: Set a timer for three times a day. Instead of asking “How do I feel?”, ask “Is my heart racing? Are my shoulders tight? Is my head hot?” Use physical cues to gauge your stress level before it hits 100.