Have you ever found yourself avoiding a task you genuinely want to do? Maybe it’s a creative hobby, a game you love, or a long-awaited project. You care about it—you even look forward to it—yet when the moment comes, you freeze. For many people with ADHD, this baffling pattern is frustratingly familiar.

One ADHDer described it like this:

“I want to play my favorite video game, but it feels like I have to mentally prepare myself. I sit there, frozen, even though I want to do it.”

This isn’t laziness or disinterest. It’s often a form of executive dysfunction—a disconnect between intention and action that leaves you feeling stuck and confused.

You want to do the thing. You care about it. But you just… can’t start.

The ADHD Paradox: Wanting to Start, But Feeling Stuck

“Why am I avoiding something I like?”

This question torments many ADHDers. It’s especially painful because it goes against logic. If you love something, shouldn’t you naturally want to do it?

One frustrated forum user shared this thought:

“I’m pretty sure that procrastinating on things you really want to do should be a diagnostic criterion for ADHD.”

This is one of the most baffling aspects of living with ADHD. Many people experience a mismatch between what they enjoy and what they’re able to act on.

This inconsistency leads to self-doubt and guilt. You start wondering if maybe you don’t really care about your interests, or worse, that you’re lazy.

ADHD expert Dr. Russell Barkley explained this paradox best: “ADHD is not a disorder of knowing what to do. It’s a disorder of doing what you know.”

You may love painting, gaming, gardening, or reading. But without the neurological conditions to support action, your brain stalls.

Why Interest Isn’t Enough: The Role of Executive Dysfunction

People often assume that if you truly want to do something, you’ll do it. But ADHD doesn’t work that way.

Executive dysfunction makes it hard to:

- Start a task, even when it’s enjoyable

- Transition between activities (especially from rest to action)

- Break a task into manageable steps

This disconnect leads to a frustrating experience: you care, but you can’t begin.

Imagine the brain as a car:

Most people can press the gas when needed, but the ADHD brain’s gas pedal (the motivation circuit) often sticks or stalls, especially if the task lacks immediate urgency.

Transitions can be particularly tough – switching from a restful state (or from another activity) into “go mode” may feel like trying to start a cold engine.

You might dread the process of setting up or the first few minutes of effort, even if you know you’ll enjoy the activity once you get going. This can make fun tasks feel oddly heavy.

The Dopamine Disconnect: How ADHD Brains Process Reward

ADHD is linked to differences in how the brain processes dopamine, a chemical involved in motivation and reward. This doesn’t just affect whether you start tasks—it affects how your brain values them.

In neurotypical brains, enjoyable tasks trigger a steady dopamine release that encourages follow-through. But ADHD brains often require a higher level of stimulation to get the same effect.

This means even fun tasks can feel oddly inaccessible, especially if they’re familiar or low-pressure.

Psychiatrist Dr. William Dodson calls this an “interest-based nervous system.” People with ADHD are primarily motivated by:

- Interest

- Challenge

- Novelty

- Urgency

If a task lacks those qualities—even if it’s something you love—it might not generate enough internal drive to begin.

The brain isn’t saying “this isn’t fun”; it’s saying “this isn’t stimulating enough right now to override inertia.”

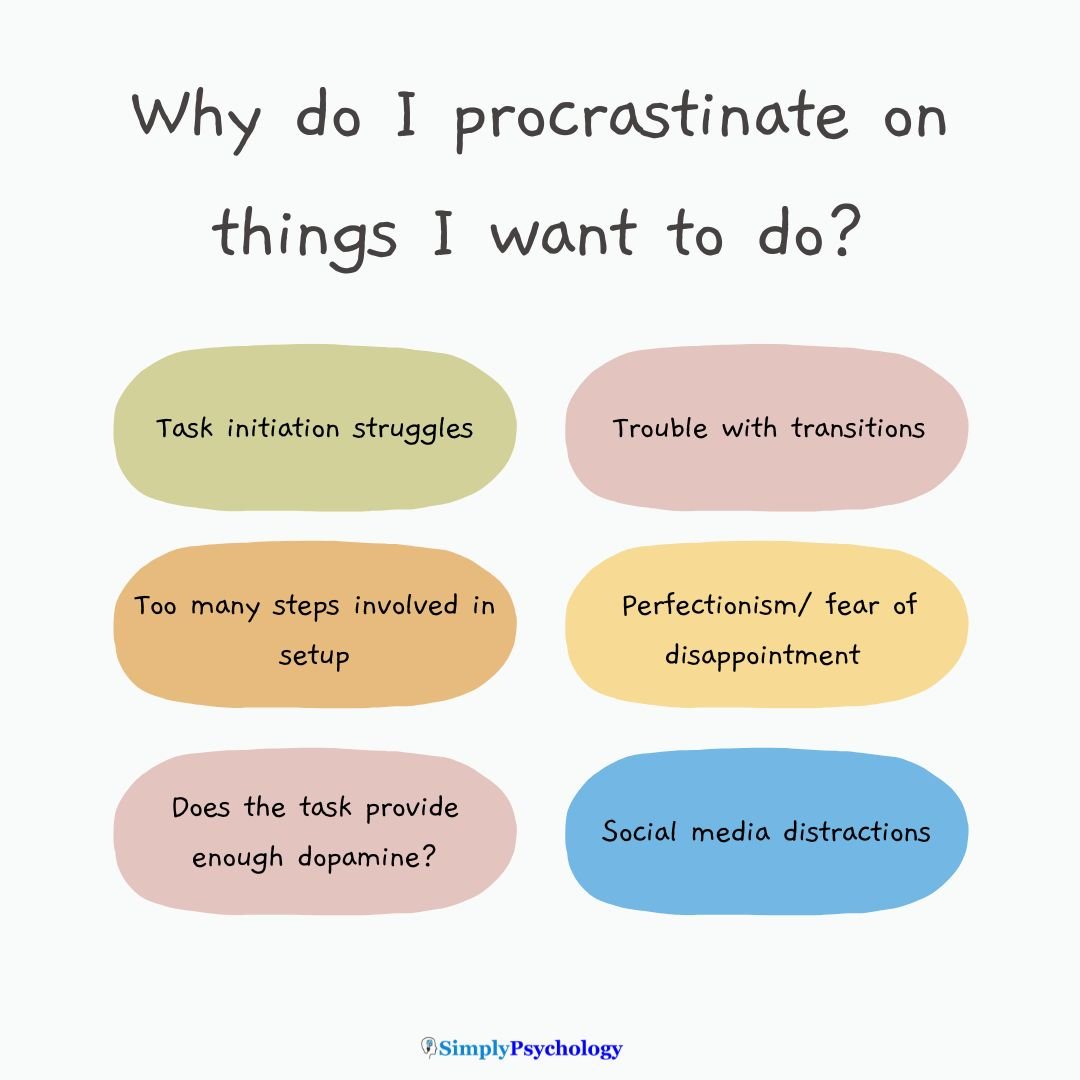

Common Barriers That Stall Enjoyable Tasks

Even when something matters to you, the ADHD brain can get stuck. Here are some common internal blocks:

1. Task Initiation Trouble

Even starting can feel like a mountain. Your mind might go blank, or your body just won’t move. This is part of executive dysfunction—not a character flaw.

2. Transitions Are Hard

Switching from one activity to another can create mental friction. Moving from rest to action is especially hard.

You might sit on the couch for hours, knowing what you want to do, but unable to shift gears.

3. Setup Overwhelm

Enjoyable tasks often come with setup: clearing a space, gathering tools, choosing where to begin. For ADHD brains, these initial steps can feel disproportionately hard.

“I love drawing, but just thinking about setting up my workspace makes me want to crawl under a blanket.”

4. All-or-Nothing Thinking

If you can’t do the whole task perfectly or without interruption, you might avoid starting. ADHD perfectionism often sounds like:

- “I don’t have enough time to do it right.”

- “If I start, I have to finish it all.”

5. Fear of Disappointment

You may worry that starting the activity won’t live up to how it feels in your head. Avoiding it protects the fantasy—but also prevents fulfillment.

6. Role of Social Media

Scrolling social media on our phones is an appealing activity for people with ADHD because it provides endless amounts of dopamine.

Often, people with ADHD may choose to spend time on social media, procrastinating on a hobby because it is the easiest available option.

The Emotional Toll of Avoiding What You Love

Avoidance of enjoyable tasks isn’t just frustrating—it’s emotionally painful. You may feel shame, sadness, or confusion. It can erode self-trust. As one person put it:

“It feels like my brain is betraying me. I want to do this thing so badly, and yet I keep putting it off.”

This kind of experience can lead to a loop of self-criticism:

- “I must not care enough.”

- “I’m wasting my time and potential.”

- “I don’t even deserve to enjoy things.”

Understanding that these patterns come from neurological differences is essential.

You’re not choosing to avoid what you enjoy. You’re navigating a brain that processes motivation and activation differently.

Breaking the Cycle: How to Start When You Feel Stuck

You can’t force your brain to work like a neurotypical one. But you can build bridges around the stuck points. Here are supportive, realistic ways to begin engaging with the things you love.

1. Start Smaller Than You Think You Should

Lower the bar until it feels almost silly.

- Want to paint? Just lay out the brushes.

- Want to play guitar? Tune it, then walk away.

- Want to read? Open the book and read one paragraph.

Once you start, momentum may build. But even if it doesn’t, you took action.

“I told myself I only had to sketch for two minutes. I ended up drawing for an hour. But even if I hadn’t, those two minutes still mattered.”

2. Make the First Step Easy to Spot

When a task feels too big, break it down until the starting point is obvious.

- Instead of “write a blog post,” try: “open Google Docs.”

- Instead of “clean the craft table,” try: “put one item away.”

Use visual cues or sticky notes to guide your brain toward that first move.

3. Create a Gentle Transition Ritual

Moving from rest to action can be jarring. Create a consistent signal that helps shift gears.

Try:

- A playlist you only play when transitioning

- A 5-minute body stretch or walk

- Lighting a candle before creative time

These cues help your brain associate routine with reward.

4. Reignite Interest with Novelty or Challenge

If your hobby feels stale, reframe it:

- Add a fun twist (e.g., draw with your non-dominant hand)

- Join a themed challenge or community event

- Set a playful constraint (e.g., write a story in 100 words)

Changing the context can rekindle dopamine and motivation.

5. Use a Body Double or Buddy

Sometimes just having someone nearby helps you begin.

- Invite a friend to co-work (virtually or in person)

- Join a “focus room” online

- Tell someone your goal and check in later

This creates accountability without pressure.

6. Let Go of “Perfect” Starts

Give yourself permission to do a messy or partial version.

- You don’t need to finish

- It doesn’t need to be good

- You don’t need to feel like it

What matters is engaging at all. That counts.

7. Celebrate Any Forward Movement

ADHD brains respond well to positive reinforcement. Acknowledge every effort:

- “I opened the file—that’s a win.”

- “I showed up for five minutes. I tried.”

- “That was hard, and I did it anyway.”

Shame blocks action. Compassion builds momentum.

8. Adjust Social Media Habits

As social media can be a tempting procrastination tool, try to change your habits around this:

- Remove apps or set time limits for how long apps are used

- Try not to use social media as a “transition activity” before doing another activity

- Ask yourself, “What is my intent with opening this app right now?” before using the app

Final Thoughts

If you’ve been putting off things you enjoy, you’re not alone—and you’re not broken.

ADHD makes initiating tasks hard, even when they bring joy. The problem isn’t your desire, it’s the friction between intention and action.

Understanding what’s happening in your brain can reduce shame and open new paths forward. With the right support, structure, and mindset, you can gently reconnect with the things that light you up.

You deserve to enjoy your passions—not just in theory, but in practice. And even if it takes time to start, each step you take still counts.