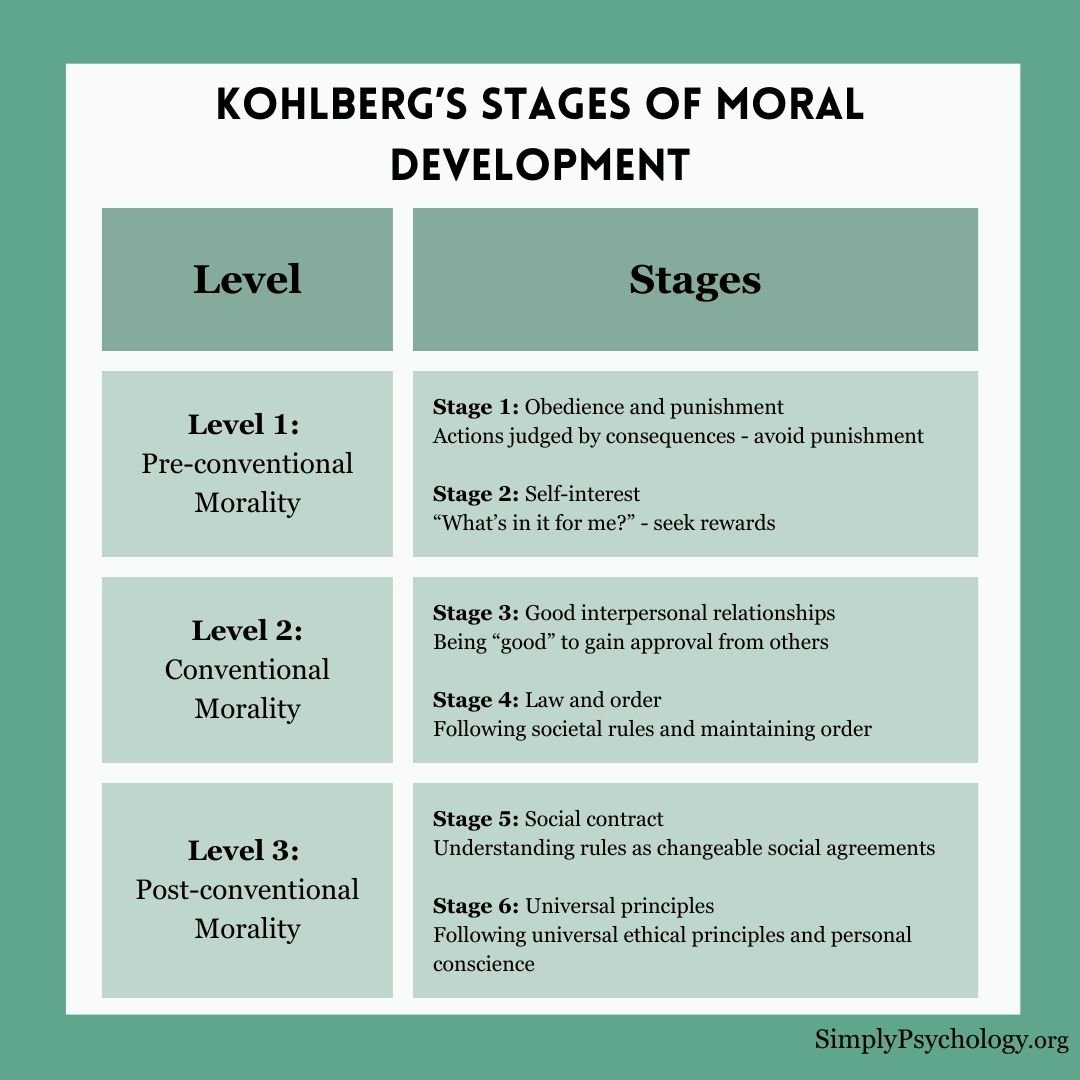

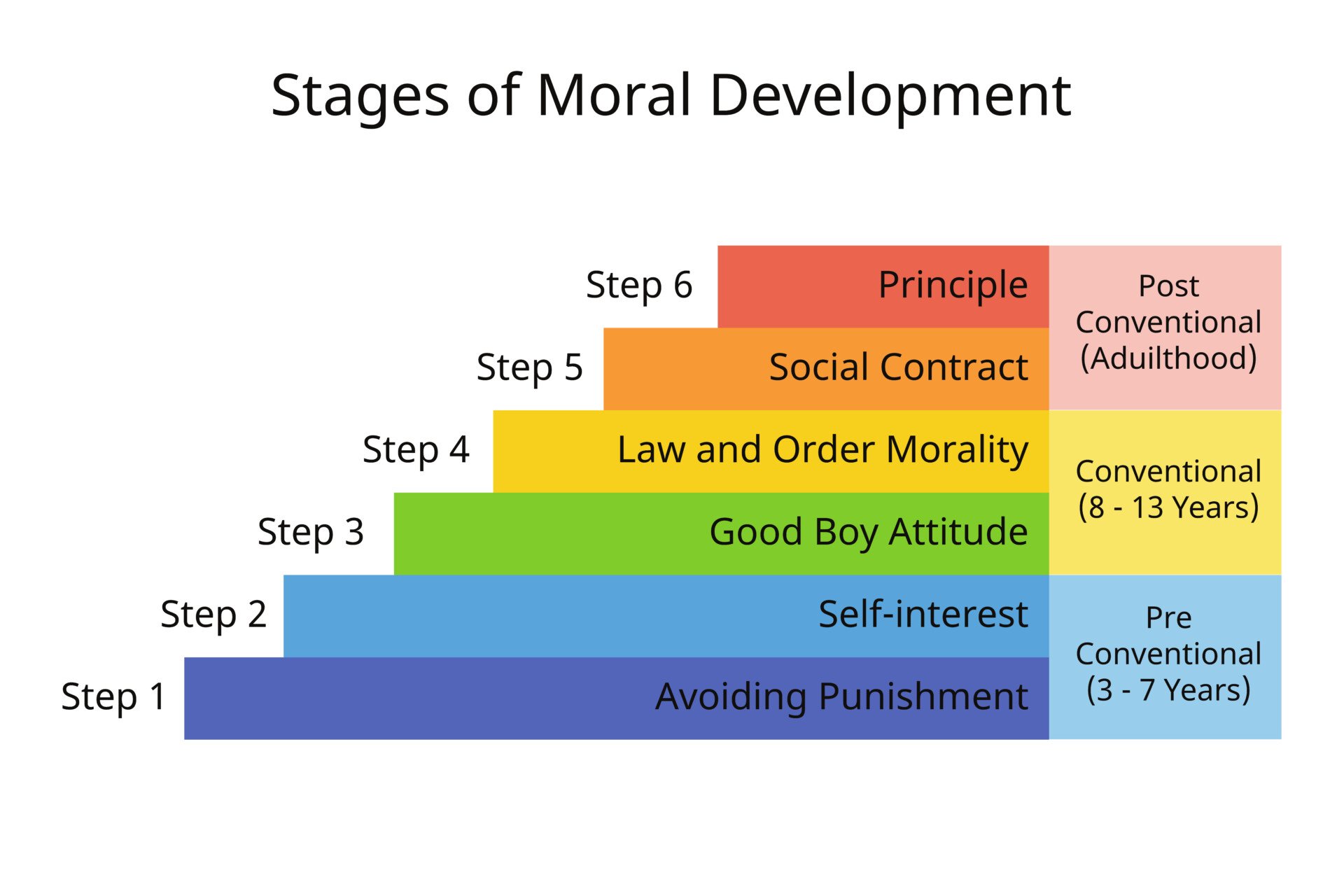

Kohlberg’s theory of moral development outlines how individuals progress through six stages of moral reasoning, grouped into three levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

At each level, people make moral decisions based on different factors, such as avoiding punishment, following laws, or following universal ethical principles.

This theory shows how moral understanding evolves with age and experience.

Summary

1. Preconventional Level (Childhood)

Focus: Decisions based primarily on self-interest and avoiding punishment.

- Stage 1: Obedience and Punishment Orientation (avoiding punishment). For example, a child doesn’t take cookies because they fear being scolded by their parent.

- Stage 2: Self-Interest Orientation (personal benefit). For example, a child helps clean up toys because they expect a reward afterward.

2. Conventional Level (Adolescence and Adulthood)

Focus: Decisions guided by social expectations, relationships, laws, and societal order.

- Stage 3: Interpersonal Accord and Conformity (meeting social expectations). For example, a teenager agrees to volunteer because friends view volunteering positively.

- Stage 4: Authority and Maintaining Social Order (obeying laws and maintaining social order). For example, an adult decides not to speed because it’s important to obey traffic laws to maintain safety.

3. Postconventional Level (Advanced Moral Reasoning)

Focus: Decisions guided by higher ethical principles and individual rights beyond societal laws.

- Stage 5: Social Contract and Individual Rights (social agreements and prioritizing human life). For example, a citizen participates in a peaceful protest to advocate for human rights, despite potential legal consequences.

- Stage 6: Universal Ethical Principles (universal ethical principles – justice, human rights). For example, a whistleblower exposes corruption in their company, recognizing the greater good outweighs personal risk.

What is an example of moral development theory in real life?

An example is a student who witnesses cheating on an important exam. The student is faced with the dilemma of whether to report the cheating or keep quiet.

A person at the pre-conventional level of moral development might choose not to report cheating because they fear the consequences or because they believe that everyone cheats.

A person at the conventional level might report cheating because they believe it is their duty to uphold the rules and maintain fairness in the academic environment.

A person at the post-conventional level might weigh the ethical implications of both options and make a decision based on their principles and values, such as honesty, fairness, and integrity, even if it may come with negative consequences.

This example demonstrates how moral development theory can help us understand how individuals reason about ethical dilemmas and make decisions based on their moral reasoning.

Level 1 – Preconventional Morality

Preconventional morality is the first level of moral development, typically lasting until approximately age 8.

During this level, children don’t have their own personal sense of right and wrong yet.

At the preconventional level, moral authority comes from outside the individual.

Children accept the moral code of authority figures such as parents and teachers rather than developing their own understanding of what is right or wrong.

Consequences Shape Moral Judgment

Children at the preconventional level base their moral judgments on the consequences of their actions:

-

Punishment and Obedience Orientation: If an action results in punishment, it is perceived as “bad.”

-

Instrumental Purpose Orientation: If an action brings about a reward or positive outcome, it is seen as “good.”

For example, a child might consider their behavior to be “good” if they receive a reward like candy for following instructions, and “bad” if they are scolded for misbehaving.

Self-Centered Moral Reasoning

In this stage, children’s moral reasoning is often self-centered. They focus on how actions affect them personally, rather than on a broader understanding of fairness or ethics.

Their moral decisions are motivated by a desire to avoid punishment and gain rewards, rather than adhering to internal moral principles.

At this stage, children accept the rules and moral codes of authority figures, such as parents, teachers, and caregivers, without fully understanding the underlying reasons for them.

Stage 1: Obedience and Punishment Orientation

Moral decisions are driven by the desire to avoid punishment. Individuals perceive rules as fixed and absolute, without considering intent.

Right and wrong are determined by direct consequences, especially punishment.

Stage 2: Self-Interest Orientation

Individuals recognize varying viewpoints but base decisions primarily on self-interest.

Actions are judged right if they serve personal needs or involve equal exchange (“what’s in it for me?”).

Reciprocity is transactional, not moral.

Level 2 – Conventional Morality

The conventional level represents the adolescent phase of moral development, where individuals begin to focus on societal norms and external expectations to discern right from wrong.

This stage is often grounded in tradition, cultural practices, or established codes of conduct.

Internalization of Authority and Group Norms

At this level, most adolescents and adults internalize the moral standards of valued adult role models.

Authority is internalized but not questioned, and reasoning is based on the norms of the group to which the person belongs.

Children at this stage believe that social rules and the expectations of others determine what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior.

Importance of Social Order and Responsibility

A social system that stresses the responsibilities of relationships and social order is seen as desirable and must, therefore, influence our views of right and wrong.

People who follow conventional morality believe that it’s important to follow society’s rules and expectations to maintain order and prevent problems.

For example, refusing to cheat on a test is a part of conventional morality because cheating can harm the academic system and create societal problems.

Stage 3. Good Interpersonal Relationships

Morality is guided by social approval and maintaining relationships.

Individuals aim to be seen as “good” by others, emphasizing trust, loyalty, and conformity to social roles and expectations.

Actions reflect the desire to please others.

Stage 4. Authority and Maintaining Social Order

Individuals prioritize law, order, and societal stability.

Moral decisions uphold laws and authority, viewing societal rules as critical for collective well-being.

Maintaining social order and fulfilling obligations is paramount.

Level 3 – Postconventional Morality

The postconventional level represents the third and highest stage of moral development in Kohlberg’s theory.

At this level, what is considered morally right is based on an individual’s understanding of universal ethical principles, not merely social norms or authority.

Personal Ethical Principles and Independent Reasoning

At this stage, moral reasoning centers on abstract concepts such as fairness, justice, and fundamental human values.

People at the postconventional level consider how their choices might affect others and strive to make decisions that benefit everyone, not just themselves.

Focus on Abstract Concepts of Justice and Fairness

At this level, moral reasoning centers on abstract concepts such as fairness, justice, and fundamental human values.

People consider how their choices might affect others and strive to make decisions that benefit everyone, not just themselves.

Individual judgment is based on self-chosen principles, with a focus on individual rights and justice.

The values that guide postconventional morality are often abstract and include concepts like the preservation of life and the importance of human dignity.

Universal Principles Over Social Norms

While these principles may be difficult to precisely define, they serve as the foundation for moral reasoning at this stage.

According to Kohlberg, only 10-15% of people reach this advanced level of moral reasoning, as it requires the capacity for abstract thinking necessary for stages 5 or 6 (postconventional morality).

Most people derive their moral views from those around them, while only a minority develop and think through ethical principles independently.

Stage 5. Social Contract and Individual Rights

The child/individual becomes aware that while rules/laws might exist for the good of the greatest number, there are times when they will work against the interest of particular individuals.

The issues are not always clear-cut.

For example, in Heinz’s dilemma, the protection of life is more important than breaking the law against stealing.

Stage 6. Universal Principles

People at this stage have developed their own set of moral guidelines, which may or may not fit the law.

The principles apply to everyone. E.g., human rights, justice, and equality.

The person will be prepared to act to defend these principles even if it means going against the rest of society in the process and having to pay the consequences of disapproval and or imprisonment.

Kohlberg doubted few people had reached this stage.

Examples of universal principles

Moral reasoning is guided by universal ethical principles like justice, equality, and human rights.

Individuals act according to self-chosen ethical principles that transcend societal rules. Decisions aim at justice and dignity for all, often at personal cost.

- Equal human rights: Someone at this stage would believe in the fundamental right of all individuals to life, liberty, and fair treatment. They would advocate for and act according to these rights, even if it meant opposing laws or societal norms.

- Justice for all: A person at this stage believes in justice for all individuals and would strive to ensure fairness in all situations. For example, they might campaign against a law they believe to be unjust, even if it is widely accepted by society.

- Non-violence: A commitment to non-violence could be a universal principle for some at this stage. For instance, they might choose peaceful protest or civil disobedience in the face of unjust laws or societal practices.

- Social contract: People at this stage might also strongly believe in the social contract, wherein individuals willingly sacrifice some freedoms for societal benefits. However, they also understand that these societal norms can be challenged and changed if they infringe upon the universal rights of individuals.

- Respect for human dignity and worth: Individuals at this stage view each person as possessing inherent value, and this belief guides their actions and judgments. They uphold the dignity and worth of every individual, regardless of social status or circumstance.

Heinz Dilemma

The Heinz dilemma is a moral question proposed by Kohlberg in his studies on moral development.

It involves a man named Heinz who considers stealing a drug he cannot afford to save his dying wife, prompting discussion on the moral implications and justifications of his potential actions.

Lawrence Kohlberg (1958) agreed with Piaget’s (1932) theory of moral development in principle but wanted to develop his ideas further.

He used Piaget’s storytelling technique to tell people stories involving moral dilemmas.

In each case, he presented a choice to be considered, for example, between the rights of some authority and the needs of some deserving individual unfairly treated.

After presenting people with various moral dilemmas, Kohlberg categorized their responses into different stages of moral reasoning.

Using children’s responses to a series of moral dilemmas, Kohlberg established that the reasoning behind the decision was a greater indication of moral development than the actual answer.

The Story

One of Kohlberg’s best-known stories (1958) concerns Heinz, who lived somewhere in Europe.

Heinz’s wife was dying from a particular type of cancer. Doctors said a new drug might save her.

The drug had been discovered by a local chemist, and the Heinz tried desperately to buy some, but the chemist was charging ten times the money it cost to make the drug, and this was much more than the Heinz could afford.

Heinz could only raise half the money, even after help from family and friends. He explained to the chemist that his wife was dying and asked if he could have the drug cheaper or pay the rest of the money later.

The chemist refused, saying that he had discovered the drug and was going to make money from it. The husband was desperate to save his wife, so later that night he broke into the chemist’s and stole the drug.

Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?

Kohlberg asked a series of questions such as:

- Should Heinz have stolen the drug?

- Would it change anything if Heinz did not love his wife?

- What if the person dying was a stranger, would it make any difference?

- Should the police arrest the chemist for murder if the woman dies?

By studying the answers from children of different ages to these questions, Kohlberg hoped to discover how moral reasoning changed as people grew older.

The sample comprised 72 Chicago boys aged 10–16 years, 58 of whom were followed up at three-yearly intervals for 20 years (Kohlberg, 1984).

Each boy was given a 2-hour interview based on the ten dilemmas. Kohlberg was interested not in whether the boys judged the action right or wrong but in the reasons for the decision. He found that these reasons tended to change as the children got older.

The Moral Stages in Action

Kohlberg identified three levels of moral reasoning: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. Each level has two sub-stages.

People can only pass through these levels in the order listed. Each new stage replaces the reasoning typical of the earlier stage. Not everyone achieves all the stages.

Preconventional Morality

Stage 1: Avoiding Punishment

- Definition: Moral reasoning is based on direct consequences.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should not steal the drug because stealing is illegal, and he could be punished.

Stage 2: Self-Interest

- Definition: Actions are seen in terms of rewards rather than moral value.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should not steal the drug because stealing is illegal, and he could be punished.

Conventional Morality

Stage 3: Good boy attitude

- Definition: Good behavior is about living up to social expectations and roles.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should steal the drug because, as a good husband, he is expected to do whatever he can to save his wife.

Stage 4: Law & Order Morality

- Definition: Moral reasoning considers societal laws.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should not steal the drug because he must uphold the law and maintain societal order.

Postconventional Morality

Stage 5: Social Contract

- Definition: Rules are seen as social agreements that can be changed when necessary.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should steal the drug because preserving human life is a more fundamental value than property rights.

Stage 6: Universal Principles

- Definition: Moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles and justice.

- Heinz Dilemma Response: Heinz should consider non-violent civil disobedience or negotiation with the pharmacist. The decision reflects a conflict between property rights and the sanctity of human life.

Disequilibrium plays a crucial role in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development.

A child encountering a moral issue may recognize limitations in their current reasoning approach, often prompted by exposure to others’ viewpoints.

Improvements in perspective-taking are key to progressing through Kohlberg’s stages of moral development.

As children mature, they increasingly understand issues from others’ viewpoints.

For instance, a child at the preconventional level typically perceives an issue primarily in terms of personal consequences.

In contrast, a child at the conventional level tends to consider the perspectives of others more substantially.

What were some other moral dilemmas Kohlberg used in his research?

In addition to the Heinz Dilemma, Kohlberg presented nine other moral dilemmas in his interviews.

The entire collection of ten dilemmas was designed to create moral conflict by pitting one ethical norm (e.g., property rights, law, or authority) against another (e.g., compassion, human life, or fairness).

This structure allowed Kohlberg to assess how individuals reasoned through complex moral situations, providing the foundation for his six-stage model of moral development.

Examples of Kohlberg’s Moral Dilemmas

-

The Heinz Dilemma: Heinz must decide whether to steal an expensive drug to save his dying wife, raising questions about obeying the law versus preserving life.

-

The Value of Human Life Dilemma: A starving person considers stealing food to survive, forcing a choice between the sanctity of life and respect for property rights.

-

The Drowning Girl Dilemma: A man witnesses a girl drowning and must decide whether to risk his own life to save her, despite her being a stranger.

-

The Joe Dilemma: A boy named Joe must choose between using his earnings for summer camp or giving the money to his father to fix the family car, testing obedience and fairness within family relationships.

-

The Doctor’s (Dr. A) Dilemma: A doctor faces whether to give a terminally ill patient a lethal dose at their request, confronting the ethics of mercy killing and professional duty.

-

The Judge’s Dilemma: A judge must decide between enforcing the law strictly and showing compassion toward a young offender who acted under difficult circumstances.

-

The Officer Brown Dilemma: A police officer must determine whether to arrest a man who stole food to feed his family, balancing justice, empathy, and the rule of law.

-

The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Two prisoners must choose between betraying each other or staying silent, revealing how self-interest and trust influence moral reasoning.

-

The Terry Dilemma: Terry learns a close friend caused a hit-and-run accident and must decide whether to protect the friend or tell the truth to the police, testing honesty and loyalty.

-

The Newspaper (or Confidentiality) Dilemma: A reporter must decide whether to protect a confidential source or reveal their identity to prevent harm, weighing professional integrity against public safety.

These scenarios, like the Heinz case, aimed to reveal how people justify moral decisions rather than what choice they make.

Kohlberg used a set of 10 moral dilemmas in total, forming the basis of his Moral Judgment Interview (MJI).

How did Kohlberg score the responses to his dilemmas?

Kohlberg scored responses using the Moral Judgment Interview (MJI) — a structured interview system he designed to assess the reasoning behind moral decisions.

Each participant was presented with a series of moral dilemmas and follow-up questions exploring why they believed an action was right or wrong.

Scoring and Classification

Responses were then coded and classified into one of six stages of moral reasoning, based not on the decision itself but on the underlying justification.

For example, reasoning focused on avoiding punishment reflected Stage 1, seeking approval reflected Stage 3, and appealing to universal ethical principles reflected Stage 6.

Scoring involved identifying consistent patterns in reasoning across multiple dilemmas, forming what Kohlberg called a “moral stage profile.”

For a person to be formally classified at a particular stage, they must demonstrate reasoning at that stage 50% or more of the time across the dilemmas, showing that the stage represents their preferred and dominant way of thinking about moral issues.

His later standardized scoring manual (Colby & Kohlberg, 1983) enhanced reliability by defining specific criteria for each stage, ensuring that different researchers could classify responses consistently.

Problems with Kohlberg’s Methods

1. The dilemmas are artificial (i.e., they lack ecological validity)

Most dilemmas are unfamiliar to most people (Rosen, 1980).

For example, it is all very well in the Heinz dilemma, asking subjects whether Heinz should steal the drug to save his wife.

However, Kohlberg’s subjects were aged between 10 and 16. They have never been married, and never been placed in a situation remotely like the one in the story.

How should they know whether Heinz should steal the drug?

2. The sample is biased

Kohlberg’s (1969) theory suggested males more frequently progress beyond stage four in moral development, implying females lacked moral reasoning skills.

His research assistant, Carol Gilligan, disputed this, who argued that women’s moral reasoning differed, not deficient.

She criticized Kohlberg’s theory for focusing solely on upper-class white males, arguing women value interpersonal connections.

For instance, women often oppose theft in the Heinz dilemma due to potential repercussions, such as separation from his wife if Heinz is imprisoned.

Gilligan (1982) conducted new studies interviewing both men and women, finding women more often emphasized care, relationships and context rather than abstract rules.

Gilligan argued that Kohlberg’s theory overlooked this relational “different voice” in morality.

According to Gilligan (1977), because Kohlberg’s theory was based on an all-male sample, the stages reflect a male definition of morality (it’s androcentric).

Men’s morality is based on abstract principles of law and justice, while women’s is based on principles of compassion and care.

Further, the gender bias issue raised by Gilligan is a reminder of the significant gender debate still present in psychology, which, when ignored, can greatly impact the results obtained through psychological research.

3. The dilemmas are hypothetical (i.e., they are not real)

Kohlberg’s approach to studying moral reasoning relied heavily on his semi-structured moral judgment interview.

Participants were presented with hypothetical moral dilemmas, and their justifications were analyzed to determine their stage of moral reasoning.

Some critiques of Kohlberg’s method are that it lacks ecological validity, removes reasoning from real-life contexts, and defines morality narrowly in terms of justice reasoning.

Psychologists concur with Kohlberg’s moral development theory, yet emphasize the difference between moral reasoning and behavior.

What we claim we’d do in a hypothetical situation often differs from our actions when faced with the actual circumstance. In essence, our actions might not align with our proclaimed values.

Real-Life Context and Consequences

In a real situation, what course of action a person takes will have real consequences – and sometimes very unpleasant ones for themselves.

Would subjects reason in the same way if they were placed in a real situation? We don’t know.

The fact that Kohlberg’s theory is heavily dependent on an individual’s response to an artificial dilemma questions the validity of the results obtained through this research.

People may respond very differently to real-life situations that they find themselves in than they do to an artificial dilemma presented to them in the comfort of a research environment.

4. Poor research design

How Kohlberg carried out his research when constructing this theory may not have been the best way to test whether all children follow the same sequence of stage progression.

His research was cross-sectional, meaning that he interviewed children of different ages to see their moral development level.

A better way to see if all children follow the same order through the stages would be to conduct longitudinal research on the same children.

However, longitudinal research on Kohlberg’s theory has since been carried out by Colby et al. (1983), who tested 58 male participants of Kohlberg’s original study.

She tested them six times in 27 years and supported Kohlberg’s original conclusion, which is that we all pass through the stages of moral development in the same order.

Contemporary research employs more diverse methods beyond Kohlberg’s interview approach, such as narrative analysis, to study moral experience. These newer methods aim to understand moral reasoning and development within authentic contexts and experiences.

Tappan and colleagues (1996) promote a narrative approach that examines how individuals construct stories and identities around moral experiences.

This draws from the sociocultural tradition of examining identity in context. Tappan argues narrative provides a more contextualized understanding of moral development.

Colby and Damon’s (1992) empirical research uses in-depth life story interviews to study moral exemplars – people dedicated to moral causes.

Instead of hypothetical dilemmas, they ask participants to describe real moral challenges and commitments.

Their goal is to respect exemplars as co-investigators of moral meaning-making.

Walker and Pitts’ (1995) studies use open-ended interviews asking people to discuss real-life moral dilemmas and reflect on the moral domain in their own words.

This elicits more naturalistic conceptions of morality compared to Kohlberg’s abstract decontextualized approach.

Problems with Kohlberg’s Theory

1. Are there distinct stages of moral development?

Kohlberg claims there are, but the evidence does not always support this conclusion.

For example, a person who justified a decision based on principled reasoning in one situation (postconventional morality stage 5 or 6) would frequently fall back on conventional reasoning (stage 3 or 4) with another story.

In practice, it seems that reasoning about right and wrong depends more on the situation than on general rules.

Moreover, individuals do not always progress through the stages, and Rest (1979) found that one in fourteen slipped backward.

The evidence for distinct stages of moral development looks very weak. Some would argue that behind the theory is a culturally biased belief in the superiority of American values over those of other cultures and societies.

Gilligan’s Perspective

Gilligan (1982) did not dismiss developmental psychology or morality. She acknowledged that children undergo moral development in stages and even praised Kohlberg’s stage logic as “brilliant” (Jorgensen, 2006, p. 186).

However, she preferred Erikson’s model over the more rigid Piagetian stages.

While Gilligan supported Kohlberg’s stage theory as rational, she expressed discomfort with its structural descriptions that lacked context.

She also raised concerns about the theory’s universality, pointing out that it primarily reflected Western culture (Jorgensen, 2006, pp. 187-188).

Neo-Kohlbergian Schema Model

Rest and colleagues (1979) have developed a theoretical model building on but moving beyond Kohlberg’s stage-based approach to moral development.

Their model outlines four components of moral behavior: moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character.

For the moral judgment component, Rest et al. propose that individuals use moral schemas rather than progress through discrete stages of moral reasoning.

Schemas are generalized knowledge structures that help us interpret information and situations.

An individual can have multiple schemas available to make sense of moral issues, rather than being constrained to a single developmental stage.

Some examples of moral schemas proposed by Rest and colleagues include:

- Personal Interest Schema – focused on individual interests and preferences

- Maintaining Norms Schema – emphasizes following rules and norms

- Postconventional Schema – considers moral ideals and principles

Rather than viewing development as movement to higher reasoning stages, the neo-Kohlbergian approach sees moral growth as acquiring additional, more complex moral schemas. Lower schemas are not replaced, but higher order moral schemas become available to complement existing ones.

The schema concept attempts to address critiques of the stage model, such as its rigidity and lack of context sensitivity. Using schemas allows for greater flexibility and integration of social factors into moral reasoning.

2. Does moral judgment match moral behavior?

Kohlberg never claimed that there would be a one-to-one correspondence between thinking and acting (what we say and what we do), but he does suggest that the two are linked.

However, Bee (1994) suggests that we also need to take into account of:

a) habits that people have developed over time.

b) whether people see situations as demanding their participation.

c) the costs and benefits of behaving in a particular way.

d) competing motive such as peer pressure, self-interest and so on.

Overall, Bee points out that moral behavior is only partly a question of moral reasoning. It also has to do with social factors.

3. Is justice the most fundamental moral principle?

This is Kohlberg’s view. However, Gilligan (1977) suggests that the principle of caring for others is equally important.

Furthermore, Kohlberg claims that the moral reasoning of males has often been in advance of that of females.

Girls are often found to be at stage 3 in Kohlberg’s system (good boy-nice girl orientation), whereas boys are more often found to be at stage 4 (Law and Order orientation). Gilligan (p. 484) replies:

“The very traits that have traditionally defined the goodness of women, their care for and sensitivity to the needs of others, are those that mark them out as deficient in moral development”.

In other words, Gilligan claims that there is a sex bias in Kohlberg’s theory.

He neglects the feminine voice of compassion, love, and non-violence, which is associated with the socialization of girls.

The Ethics of Care vs. The Ethics of Justice

Gilligan concluded that Kohlberg’s theory did not account for the fact that women approach moral problems from an ‘ethics of care’, rather than an ‘ethics of justice’ perspective, which challenges some of the fundamental assumptions of Kohlberg’s theory.

In contrast to Kohlberg’s impersonal “ethics of justice”, Gilligan proposed an alternative “ethics of care” grounded in compassion and responsiveness to needs within relationships (Gilligan, 1982).

Her care perspective highlights emotion, empathy and understanding over detached logic. Gilligan saw care and justice ethics as complementary moral orientations.

Walker et al. (1995) found everyday moral conflicts often revolve around relationships rather than justice; individuals describe relying more on intuition than moral reasoning in dilemmas.

This raises questions about the centrality of reasoning in moral functioning.

4. Do people make rational moral decisions?

Kohlbeg’s theory emphasizes rationality and logical decision-making at the expense of emotional and contextual factors in moral decision-making.

One significant criticism is that Kohlberg’s emphasis on reason can create an image of the moral person as cold and detached from real-life situations.

Carol Gilligan critiqued Kohlberg’s theory as overly rationalistic and not accounting for care-based morality commonly found in women.

She argued for a “different voice” grounded in relationships and responsiveness to particular individuals.

The criticism suggests that by portraying moral reasoning as primarily cognitive and detached from emotional and situational factors, Kohlberg’s theory oversimplifies real-life moral decision-making, which often involves emotions, social dynamics, cultural nuances, and practical constraints.

Critics contend that his model does not adequately capture the multifaceted nature of morality in the complexities of everyday life.

5. Cultural Variations

In more individualistic cultures (e.g., the United States), personal rights and justice-focused reasoning may dominate, aligning well with Kohlberg’s higher stages.

Conversely, in collectivist cultures (e.g., parts of East Asia), moral judgments may more strongly emphasize group harmony, duty, and obligations to family or community.

Studies by Snarey (1985) and others have shown that Stage 5 or 6 reasoning (postconventional) is not commonly found in certain traditional societies, raising questions about how universal Kohlberg’s model truly is.

Exploring Alternative Theories of Moral Development

Although Lawrence Kohlberg’s stage model is a foundational framework, moral development does not occur in a vacuum.

Several other models offer insight into how individuals learn and apply moral standards.

1. Piaget’s Two Stages of Moral Judgment

Jean Piaget’s contributions to moral development served as a significant foundation on which Lawrence Kohlberg built his more detailed, six-stage model.

While Piaget primarily focused on children’s cognitive processes (such as logical thinking and perspective-taking), he also investigated how children develop rules and moral judgments through game-playing and social interactions.

Recognizing Piaget’s theory as an alternative or complementary approach helps illustrate that moral development is not a single, linear concept but a multifaceted progression influenced by cognitive growth, social context, and peer relationships.

Piaget proposed that children move from a rigid acceptance of rules to a more cooperative and relational approach to morality:

-

Heteronomous Morality (Moral Realism)

- Typically found in children around 4–7 years old.

- Focus: Rules are seen as immutable and handed down by authority figures (parents, teachers). Moral wrongness is judged primarily by consequences rather than intent.

- Example: A child might say breaking three cups accidentally is “worse” than breaking one cup deliberately, because more cups were broken—even though the intention was different.

-

Autonomous Morality (Moral Relativism)

- Emerges around 8–10 years onward.

- Focus: Rules are recognized as flexible and shaped by social agreement. Intentions begin to matter more than outcomes.

- Example: A child might argue that breaking a single cup out of carelessness is worse than breaking three cups accidentally, because the intention or motive behind the action is taken into account.

| Aspect | Piaget | Kohlberg |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Cognitive development and children’s understanding of rules. | Moral reasoning across lifespan (childhood to adulthood). |

| Stages | 2 main stages: Heteronomous morality (rules fixed by authority) and Autonomous morality (rules negotiated and based on intent). | 3 levels (Pre-, Conventional, Post-conventional), each with 2 stages (total 6). |

| Method | Observation of children playing games and discussing rules. | Moral dilemmas and interviews (e.g., Heinz dilemma). |

| Final Authority | Moral understanding shaped by peer interaction. | Moral reasoning progresses through internal reflection and cognitive growth. |

| Role of Peers vs Adults | Peers help children move from rigid rule-following to cooperation. | Moral growth can occur through cognitive conflict, education, and discussion. |

Key Point: Piaget believed that interactions with peers, rather than authority figures, drive the transition from heteronomous to autonomous morality. Discussions and conflicts among equals help children see rules as negotiable and encourage them to understand others’ perspectives.

2. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura’s social learning theory emphasizes the role of observation and imitation in moral development.

Rather than moral reasoning being fully internal or stage-driven, Bandura suggests children (and adults) learn moral behaviors by watching others—parents, peers, media figures—and assessing the outcomes of those behaviors.

- Vicarious Reinforcement: Individuals are more likely to adopt behaviors they see rewarded and avoid those that result in punishment.

- Modeling & Self-efficacy: Learners internalize moral norms partly by identifying with certain role models, developing confidence that “I can behave morally because I’ve seen others do so successfully.”

- Implication: Social context and direct observation can shape moral conduct as much as a person’s abstract reasoning.

3. Eisenberg’s Prosocial Reasoning

Nancy Eisenberg’s research focuses on prosocial moral reasoning—how people decide whether to help others, even when it costs them personally.

- Developmental Trajectory: Similar to Kohlberg, Eisenberg outlines different levels (or orientations) of prosocial reasoning, from hedonistic (self-focused) to internalized moral values.

- Context & Emotion: Eisenberg underscores the influence of empathy and emotional understanding in moral decisions, suggesting that children’s willingness to help evolves alongside their growing capacity for perspective-taking.

- Practical Note: Real prosocial dilemmas (e.g., sharing limited resources with peers) may overlap with Kohlberg’s stages yet often emphasize concern for others over strict adherence to rules.

4. Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model

Jonathan Haidt’s model posits that moral judgments often stem from quick, automatic intuitions (e.g., feelings of disgust or empathy), while logical reasoning typically justifies decisions post hoc.

- Intuitive Primacy: Moral reasoning can be more about rationalizing intuitive reactions than constructing principles from scratch.

- Cultural Variation: Different societies foster distinct intuitive responses (e.g., emphasis on purity, hierarchy, or communal care), challenging Kohlberg’s claim of universal progression in moral logic.

- Relevance: This perspective suggests that while Kohlberg’s theory focuses on reason-based answers to dilemmas, in day-to-day life emotions and snap judgments drive moral behavior just as much—if not more.

5. Moral Reasoning and Well-Being

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi (2000) suggests that moral reasoning is closely intertwined with well-being, character strengths, and prosocial behaviors.

By linking Kohlberg’s stage-based framework to the broader context of flourishing and virtue, we gain new insights into why individuals move toward higher stages of moral reasoning—and how to support that growth in everyday life.

- Eudaimonic Fulfillment: Postconventional thinking (Stages 5 and 6) often aligns with deeper meaning and purpose. Acting on universal ethical principles—such as justice or compassion—can enhance one’s sense of integrity and psychological well-being.

- Positive Emotions: Feelings like empathy, gratitude, and moral elevation can reinforce moral ideals. For instance, experiencing gratitude after receiving help may prompt individuals to adopt more socially oriented behaviors, echoing higher-stage concerns about collective welfare.

While Kohlberg’s model focuses on the cognitive progression of moral judgment, positive emotions can serve as motivational forces that help people actualize these principles in real-world decisions.

Practical Applications

Students, educators, and professionals can apply Kohlberg’s theory (and its critiques) in everyday settings. Below are some practical, research-based approaches:

Educational Settings

-

Moral Dilemma Discussions

- Present age-appropriate dilemmas in class and encourage open debate. Ask students to articulate their reasoning, challenge each other respectfully, and consider alternative perspectives.

- Goal: Move beyond a purely rule-focused morality (Stage 4) to an understanding of societal values and universal principles (Stage 5 or 6).

-

Role-Playing and Perspective-Taking

- Assign learners roles within a moral conflict scenario (e.g., an environmental issue, a school-related ethical dispute) to simulate varied viewpoints.

- Impact: Builds empathy, expands moral perspective, and helps participants internalize different sides of an argument.

-

Plus-One Teaching Method

- The plus-one (+1) teaching strategy, developed by Kohlberg and colleagues, is an educational technique designed to promote moral development.

-

It involves presenting students with reasoning that is one stage above their current moral level.

-

Goal: To create cognitive conflict (disequilibrium) — prompting learners to reflect on and reconsider their reasoning.

-

Example: If a student reasons at Stage 3 (seeking social approval), a teacher might challenge them with Stage 4 reasoning (law and order) to encourage progression.

Character Strengths and Moral Growth

Positive psychology identifies core character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) that often map onto Kohlberg’s moral stages:

- Fairness and Justice: Correlates with the Conventional (Stage 4) emphasis on law and order, and with Stage 5’s focus on upholding social contracts for the collective good.

- Kindness and Humanity: Reflects the empathy central to Stage 3’s interpersonal relationships, and extends to universal care principles in Stage 6.

- Perspective (Wisdom): Supports the ability to weigh multiple viewpoints, bridging the gap between Conventional (societal norms) and Postconventional (universal ethical principles) reasoning.

Practical Note: Identifying and nurturing these strengths (e.g., fairness, kindness, perspective-taking) can help individuals progress through Kohlberg’s stages, not merely by learning abstract principles but by embodying them in daily life.

Positive Interventions and Activities

-

Values Reflection

- Encourage students or participants to reflect on personal virtues they admire or wish to develop (e.g., generosity, honesty).

- Discuss how these virtues might manifest at different Kohlberg stages (from simple rule-following to universal ethical commitments).

-

Gratitude Journaling

- Ask individuals to note moments of moral significance each week (e.g., witnessing a selfless act).

- Linking gratitude to moral behaviors can reinforce prosocial emotions that support postconventional thinking (Stage 5–6).

-

Service-Learning Projects

- Engage groups in projects benefiting the community (e.g., environmental clean-ups, volunteering).

- Follow up with structured debriefs on how these experiences relate to moral principles, thereby connecting action with higher-level reasoning.

Why It Matters: These techniques highlight that moral growth is not only about understanding right from wrong but feeling motivated to do good. Positive psychology thus complements Kohlberg’s stages by focusing on emotional drivers and real-life moral practice.

Parenting and Child Development

- Modeling Behavior: Children learn more from what adults consistently do than from abstract moral lectures. Demonstrating kindness, fairness, and honesty is more powerful than simply talking about these values.

- Encouraging Empathy: Activities like volunteering, team projects, and caring for pets can nurture empathy—a key emotional foundation for higher-stage moral reasoning.

Professional Training

- Ethics Workshops: Professionals (e.g., in healthcare or business) can analyze real dilemmas to practice postconventional reasoning—balancing legal rules with human values like autonomy, justice, or compassion.

- Reflective Journals: Encourage employees or trainees to document and reflect upon moral challenges they face at work, examining how they reasoned through them and whether they’d respond differently in the future.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall.

Bee, H. L. (1994). Lifespan development. HarperCollins College Publishers.

Blum, L. A. (1988). Gilligan and Kohlberg: Implications for moral theory. Ethics, 98(3), 472-491.

Colby, A., Kohlberg, L., Gibbs, J., Lieberman, M., Fischer, K., & Saltzstein, H. D. (1983). A longitudinal study of moral judgment. Monographs of the society for research in child development, 1-124.

Colby, A., Kohlberg, L., Gibbs, J., & Lieberman, M. (1983). A longitudinal study of moral judgment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 48 (1-2, Serial No. 200). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Day, J. M., & Tappan, M. B. (1996). The narrative approach to moral development: From the epistemic subject to dialogical selves. Human Development, 39(2), 67-82.

Eisenberg, N. (1982). The Development of Prosocial Behavior. Academic Press.

Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children. Cambridge University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1977). In a different voice: Women’s conceptions of self and of morality. Harvard Educational Review, 47(4), 481-517.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1995). Hearing the difference: Theorizing connection. Hypatia, 10(2), 120-127.

Haidt, J. (2001). The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Jorgensen, G. (2006). Kohlberg and Gilligan: duet or duel?. Journal of Moral Education, 35(2), 179-196.

Kohlberg, L. (1958). The Development of Modes of Thinking and Choices in Years 10 to 16. Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Chicago.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages (Essays on Moral Development, Volume 2). Harper & Row

Kohlberg, L., & Blatt, M. M. (1975). The cognitive-developmental approach to moral education. Phi Delta Kappan, 56(10), 670–677.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press.

Piaget, J. (1932). The moral judgment of the child. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Rest, J. R. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. University of Minnesota Press.

Rosen, B. (1980). Moral dilemmas and their treatment. In, Moral development, moral education, and Kohlberg. B. Munsey (Ed). (1980), pp. 232-263. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Snarey, J. R. (1985). Cross-cultural universality of social-moral development: a critical review of Kohlbergian research. Psychological bulletin, 97(2), 202.

Walker, L. J., Pitts, R. C., Hennig, K. H., & Matsuba, M. K. (1995). Reasoning about morality and real-life moral problems.