Cesare Lombroso was a 19th-century Italian criminologist often called the father of modern criminology. He believed criminals were “born,” not made, and could be identified by physical traits like facial shape or skull size. Although his ideas are now seen as outdated and unscientific, Lombroso’s work marked an early attempt to study crime through observation and data, paving the way for modern criminological research.

Key Takeaways

- Origins: Cesare Lombroso was a 19th-century Italian criminologist who pioneered the idea that criminal behavior could be studied scientifically rather than morally or legally. His work marked the birth of positivist criminology.

- Theory: He proposed that some people are “born criminals,” identifiable by physical traits such as facial asymmetry or skull shape—a concept known as atavism, suggesting a throwback to primitive humans.

- Methods: Lombroso collected data from prisoners and autopsies to find biological patterns in offenders, believing anatomy revealed moral character, though his evidence was deeply flawed.

- Criticism: Modern science rejects his theories as pseudoscientific and discriminatory, noting that criminal behavior is shaped by complex social, psychological, and environmental factors.

- Legacy: Despite his errors, Lombroso’s attempt to study crime empirically helped shift criminology toward observation, data, and the search for underlying causes of criminal behavior.

Father of Modern Criminology

Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was an Italian doctor and criminologist who played a major role in shaping the study of crime.

Lombroso’s theories were based on his revolutionary idea that criminal behavior has biological and physical roots.

He argued that crime often stems from inborn defects rather than free will or moral weakness.

This idea became the foundation of what’s called the Positive School of Criminology — a movement that aimed to study crime scientifically, focusing on the criminal rather than the crime itself.

Lombroso, often known as the “father of modern criminology,” believed that some people are born with a natural tendency toward criminal behavior, passed down through heredity.

His work rested on two key ideas:

-

The shift from studying the crime to studying the criminal, and

-

The belief that some criminals were atavistic — evolutionary throwbacks to an earlier, more primitive stage of human development.

A New Approach: Studying the Criminal, Not the Crime

Before Lombroso, most criminologists focused on laws, moral responsibility, and abstract theories about justice.

Lombroso rejected this philosophical approach and replaced it with empirical, scientific observation.

He believed that to understand crime, researchers had to study the offender’s mind and body, not just their actions.

This perspective gave rise to Criminal Anthropology — a new scientific field that studied the biological, psychological, and social traits of criminals.

Lombroso saw this as a way to understand and potentially rehabilitate offenders, not just punish them.

The “Born Criminal” and the Idea of Atavism

Lombroso’s most famous — and controversial — theory was the concept of the “born criminal” (delinquente nato).

He claimed that some people are atavistic, meaning they are evolutionary throwbacks who display the instincts and physical traits of primitive humans or even apes.

He believed these individuals were biologically destined to commit crimes because their brains and bodies hadn’t fully evolved to match modern society.

The Discovery That Sparked It All

Lombroso said his theory began during a postmortem examination of a notorious Italian bandit named Vilella.

When Lombroso opened Vilella’s skull, he found an unusual hollow at the base — which he called the median occipital fossa — similar to features found in some lower animals.

He saw this as a “revelation,” believing he had discovered physical evidence that some criminals were biologically different from normal people.

This led him to identify physical traits (which he called stigmata) that he believed were signs of a “criminal type.”

Physical Signs of the “Criminal Type” (Stigmata)

According to Lombroso, people born with criminal tendencies often shared a number of physical anomalies, including:

-

Asymmetrical faces (uneven eyes or ears, slanted nose)

-

Large jaws and protruding lower jaw

-

High cheekbones and heavy brow ridges

-

Irregular teeth

-

Long arms or unusual skull shapes

He also noted behavioral and sensory traits, such as:

-

Reduced sensitivity to pain

-

A fascination with tattoos, which he linked to primitive and tribal behavior

-

Restlessness and impulsivity

When several of these traits appeared together, Lombroso said they indicated a “born criminal.”

The Criminal Mind: Psychological and Moral Traits

Lombroso didn’t stop at physical features — he also described what he believed were the psychological and moral characteristics of born criminals.

He claimed they often showed:

-

A lack of empathy and moral sense

-

Cruelty, impulsiveness, and vanity

-

Distorted ideas of right and wrong, sometimes seeing murder or revenge as justified

-

Little or no remorse for their actions

-

Weak or abnormal family attachments, though sometimes they showed affection for animals or strangers

In his view, these traits made the born criminal emotionally and morally closer to “primitive” humans or people with epilepsy.

Later Revisions: Degeneration and Epilepsy

As Lombroso’s research developed — and as critics challenged his early ideas — he revised his theory.

While he never abandoned the concept of atavism, he came to believe that disease and brain disorders also played a key role in criminal behavior.

-

He noticed that many traits seen in criminals (such as impulsivity and lack of control) also appeared in people with epilepsy.

-

The case of Misdea, an epileptic soldier who killed several people during a seizure, reinforced this idea.

-

Lombroso began to argue that some criminals were not “throwbacks” but rather people with brain pathology or degenerative conditions.

In his later writings, he categorized offenders into different types:

-

Born criminals

-

Insane criminals

-

Epileptic criminals

He estimated that “born criminals” made up about one-third of all offenders, but believed this group was responsible for the most violent and shocking crimes.

Lombroso’s Lasting Impact

Although Lombroso’s theories are now widely criticized and rejected, they were groundbreaking for their time.

He was among the first to study crime scientifically, using observation and measurement instead of pure philosophy.

While modern criminology no longer supports his biological determinism, Lombroso’s work paved the way for research into psychological, social, and biological factors in criminal behavior.

Atavism and the Born Criminal

In his landmark book L’Uomo delinquente (The Criminal Man, 1876), Lombroso proposed that criminals were atavistic — meaning they were evolutionary throwbacks to earlier, more primitive stages of human development.

The word atavism comes from the Latin atavus, meaning “ancestor.” Lombroso used it to describe individuals who, through heredity, had reverted to primitive physical and mental types.

He argued that these people were “born criminals”, a distinct biological class of individuals who were genetically predisposed to crime.

Their primitive brains and instincts made them wild, impulsive, and unable to adapt to civilized life — leading them inevitably into criminal behavior.

This idea was influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution (On the Origin of Species, 1859).

Lombroso believed that criminals represented an earlier stage of evolution — less developed than non-criminals.

Origins of the Theory: Lombroso’s “Revelation”

Lombroso’s theory proposed that certain people were “evolutionary accidents” — individuals whose biological development had stopped at an earlier, primitive stage.

Their brains and instincts were incapable of adjusting to modern social life.

Lombroso traced the origins of his theory to two key observations:

1. Tattooing in Soldiers (1864)

While working as an army doctor, Lombroso noticed that soldiers who behaved badly were often heavily tattooed.

He saw tattooing as a primitive custom, a “throwback” to ancient tribal cultures — and therefore a sign of atavism.

2. The Skull of Vilella

The crucial moment came during an autopsy of a notorious criminal named Vilella.

Lombroso discovered a small hollow at the base of the skull, the median occipital fossa, which resembled a feature found in some lower animals, such as rodents.

He described this discovery as a “revelation” — the moment he realized that criminality could have biological roots.

He saw this as evidence that criminals were atavistic beings, relics of a more primitive stage of humanity.

This convinced him that some people were physically different because they were biologically predisposed to crime.

Physical Features of the “Born Criminal” (Atavistic Stigmata)

Lombroso claimed that “born criminals” could be recognized by a number of physical defects or stigmata of degeneration — visible signs of their primitive ancestry.

These features supposedly showed that they were less evolved than normal individuals.

| Category | Common Traits Noted by Lombroso |

|---|---|

| Head & Face | Large jaws and cheekbones, asymmetrical features, receding forehead, high brow ridges, flat or protruding nose, long lower jaw (prognathism), and uneven skull shapes. |

| Ears | Large or protruding ears, sometimes with Darwin’s tubercle (a small bump thought to be a leftover of animal ears). |

| Limbs & Body | Long arms, abnormal teeth, excessive hair, unusual chest shapes, small hands and feet, or long fingers (especially in pickpockets and thieves). |

| Sensory & Functional Traits | Reduced sensitivity to pain, great agility, strong left-handedness, and impulsive reactions. |

| Criminal Habits | Fondness for tattoos, cruel or “wicked” games, use of criminal slang, and fascination with gambling or orgies. |

Lombroso even identified specific physical traits for certain types of offenders:

-

Thieves – expressive faces, agile hands, small, restless eyes.

-

Murderers – cold, glassy stares, bloodshot eyes, and hooked noses.

-

Sex offenders – thick lips and protruding ears.

-

Female offenders – shorter, darker, more wrinkled, and smaller-skulled than “normal” women.

He argued that such traits were signs of inherited criminality, not just coincidence.

The Psychological Profile of the Born Criminal

According to Lombroso, “born criminals” also shared a characteristic psychological makeup.

They were impulsive, lacked empathy, and showed a “moral insensitivity” similar to that of primitive humans or epileptics.

He described them as:

-

Lacking moral sense and empathy

-

Cynical, vain, and cruel

-

Unable to feel guilt or remorse

-

Inverted in morality (sometimes believing murder or theft could be justified)

-

Lacking family affection, but sometimes showing odd tenderness toward animals or strangers

He also claimed they were lazy, loved gambling and alcohol, and often used slang or secret codes that reflected their supposed primitive mentality.

Illustrations from Cesare Lombroso’s L’Uomo delinquente (The Criminal Man, 1876), depicting what he believed were physical traits of “born criminals.” Lombroso used such portraits to support his theory that certain facial and cranial features—like heavy jaws, sloping foreheads, and asymmetrical faces—were signs of biological atavism. Today, these ideas are recognised as scientifically discredited but historically important in the development of criminology. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Six figures illustrating types of criminals Printed text L’Homme Criminel Lombroso, Cesar Published: 1888

Measuring Crime

The idea of the “born criminal” (delinquente-nato) comes from Cesare Lombroso’s attempt to apply science to the study of crime.

Influenced by the positivist belief that human behaviour could be measured and explained through observation and data, Lombroso tried to identify biological signs of criminality in individuals.

1. Clinical and Anthropometric Examination

Lombroso carried out systematic physical and medical examinations on large groups of offenders to identify recurring physical patterns.

He compared these findings with data from “normal” people (non-criminals) and from individuals diagnosed with mental illness, aiming to isolate what he believed were the biological markers of criminality.

His anthropometric studies – the detailed measurement and recording of body parts – were designed to collect objective, quantitative data.

He took measurements of the head, skull, face, and limbs, often alongside detailed case histories, photographs, and sketches.

Lombroso personally examined hundreds of prisoners and collected measurements from thousands of individuals, including 3,000 soldiers during his time as an army physician.

By combining medical observation with statistical data, Lombroso hoped to create a scientific profile of the criminal, treating offenders as subjects for clinical and biological study rather than moral judgment.

2. Physical Stigmata as “Signs” of Criminality

Central to Lombroso’s theory was the idea that criminals could be identified by physical stigmata—visible bodily anomalies that he believed were atavistic (evolutionary throwbacks) or degenerative in origin.

He proposed that when a person displayed a number of these anomalies together, they represented a distinct “criminal type”, biologically predisposed to crime.

These signs were thought to indicate that the person had regressed to an earlier evolutionary stage, sharing characteristics with primitive humans or even animals.

Lombroso examined over 4000 offenders (living and dead) to identify physical markers indicative of the atavistic form.

Examples of physical and functional anomalies noted by Lombroso include:

-

A depression at the base of the skull, known as the median occipital fossa, which he first discovered in the skull of the executed brigand Vilella. Lombroso believed this resembled the skull formation of lower animals and provided physical evidence for the concept of atavism.

-

Facial and cranial asymmetry, where one side of the face or skull was larger or positioned differently from the other.

-

Oversized jaws and cheekbones, or a protruding lower jaw (prognathism), which he thought reflected primitive, animal-like strength and aggression.

-

Reduced sensitivity to pain or touch, which he regarded as a sign of a duller nervous system and a lack of empathy.

-

Excessive body hair, long arms, or unusual ear shapes, which he interpreted as reminders of evolutionary ancestors.

Lombroso believed that such features were more than coincidences — they were biological evidence that criminality was innate rather than learned or chosen.

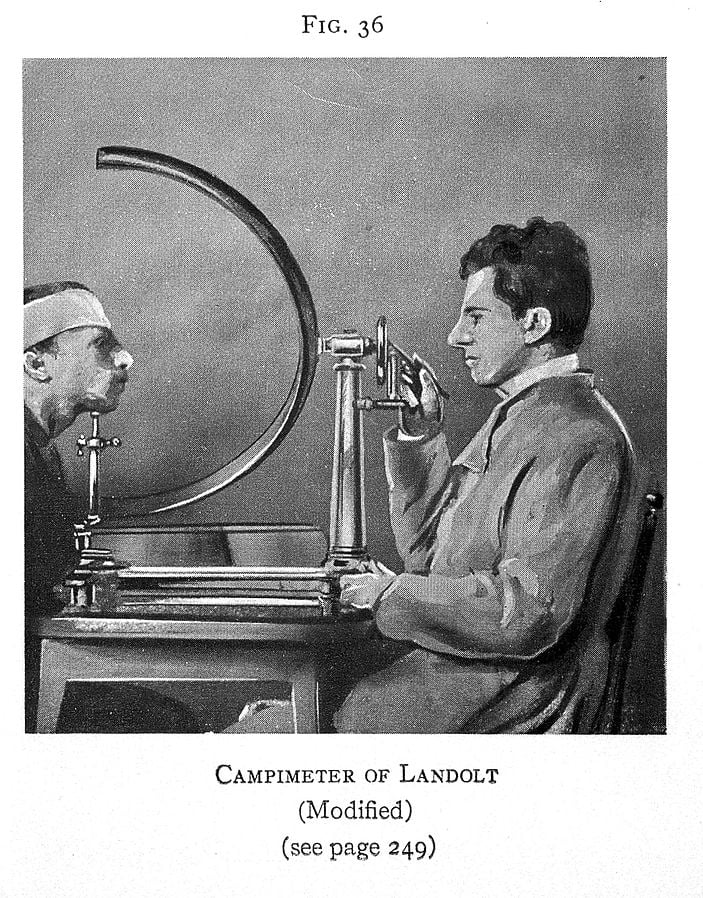

3. Instruments of Measurement

To make his research more objective and scientific, Lombroso relied on a variety of specialised measuring instruments developed by physiologists and anthropologists of his time.

Some of the key instruments he used included:

-

Craniometer – to measure skull size, capacity, and shape, allowing him to identify irregularities in brain and bone structure.

-

Esthesiometer – to test the sensitivity of the skin to touch or pain, helping him assess what he called “obtuseness of general sensibility.”

-

Dynamometer – to measure muscular strength, which Lombroso linked to impulsivity or aggression.

-

Campimeter (Landolt’s apparatus) – to test the field of vision and detect blind spots (scotoma). He believed that reduced peripheral vision was common among epileptics and “born criminals.”

Lombroso recorded his results with precision and sometimes displayed them as statistical tables or anatomical sketches.

He saw these instruments as essential tools for transforming criminology into a measurable science rather than a branch of moral philosophy.

4. Quantifying the “Born Criminal”

Lombroso did not stop at identifying physical signs — he also tried to estimate the proportion of offenders who were “born criminals.”

In his early work, he claimed that as many as 65–70% of all criminals belonged to this biologically determined category.

However, as he refined his theories and encountered more data, he later revised this estimate down to about one-third (33–40%) of offenders.

He still maintained, though, that this smaller group represented the most dangerous and significant part of the criminal population, responsible for the gravest and most violent crimes.

For Lombroso, these figures demonstrated that crime could be scientifically measured and classified, just like disease. This belief in quantification and biological determinism became a defining feature of early positivist criminology.

Occasional Criminals

Not all criminals, according to Cesare Lombroso, were “born criminals.” He believed that many people were drawn into crime by circumstance, not by biology.

These individuals, whom he called Occasional Criminals (delinquente d’occasione), represented what he termed “evolutive criminality” — a form of crime that evolved out of environment and opportunity rather than heredity.

Lombroso saw this group as existing on a continuum between the normal person and the born criminal, forming a bridge between innate and situational explanations for offending.

He divided occasional criminals into several subtypes:

1. Criminaloids

The Criminaloid represented a milder, more situational form of criminality.

Lombroso described these individuals as having only a “slight touch of degeneracy.”

Unlike the born criminal, their biological predisposition was weak and usually required an external trigger — such as opportunity, temptation, or social influence — for crime to occur.

Key Features:

-

Mild Degeneracy: Lombroso thought criminaloids suffered from a mild, “epileptoid” tendency, meaning that biological factors might exist but were only expressed when provoked by outside conditions.

-

Physical Traits: They could show minor irregularities in the skull, ears, or teeth, but not to the same extent or combination seen in born criminals. Interestingly, Lombroso noted they sometimes displayed traits like premature greying or baldness, which he claimed never appeared in born criminals.

-

Psychological Profile: Unlike born criminals, criminaloids typically committed their first offense later in life, after much hesitation or inner conflict. They often felt guilt and shame, and many preferred solitary confinement in prison to avoid mixing with hardened offenders.

-

Environmental Triggers: They were often drawn into crime by external factors — business fraud, corrupt associations, or the social influence of criminal peers. Lombroso used examples such as the Panama Canal and Bank of Rome scandals, where people of weak moral fibre engaged in large-scale fraud because the opportunity presented itself.

-

Progression to Habitual Crime: If repeatedly exposed to prison or alcohol abuse, criminaloids could gradually lose their conscience and evolve into habitual offenders, treating crime as a normal occupation.

2. Pseudo-Criminals

The Pseudo-Criminal category covered individuals whose actions technically broke the law, but were not morally corrupt or socially dangerous.

Lombroso argued that these people should not be considered true criminals at all, since their behaviour was not motivated by vice or malice.

Key Features:

-

Involuntary Acts: Their offences were often accidental, such as involuntary manslaughter, accidental arson, or unintentional harm. These individuals were physically and mentally normal, apart from a lack of prudence or foresight.

-

Crimes Against Prejudice: Others violated laws based on social or political bias rather than moral wrongdoing — for example, poaching, smuggling, evading taxes, or writing seditious materials.

-

Judgment Based on Motive: Lombroso stressed that pseudo-criminals could only be properly understood by examining their motives — whether their actions were honest mistakes or part of a pattern of genuine criminal behaviour.

He saw pseudo-criminals as normal people caught in legal definitions of crime, not as products of biological or moral degeneration.

3. Habitual Criminals

In Lombroso’s classification system, the habitual criminal belonged to the larger group of Occasional Criminals (Delinquente d’occasione).

Unlike the “born criminal,” this type did not begin life with congenital defects or biological abnormalities.

Instead, their criminality was acquired through repeated exposure to corrupting influences and a gradual adaptation to the criminal lifestyle.

Key Features

-

Lombroso believed habitual criminals were not born evil but became criminal through experience.

-

Their behaviour developed from poor upbringing, lack of education, poverty, and bad influences during youth.

-

Over time, they “fell continually lower into primitive tendencies,” losing the moral restraint that initially separated them from born criminals.

Progression from Criminaloids:

Lombroso saw habitual criminals as evolved criminaloids — individuals who had only slight degeneracy at first but who degenerate further through prison life, criminal association, or alcohol abuse.

These environmental influences transformed mild offenders into career criminals who regarded crime as a trade or occupation.

Behaviour and Appearance:

-

Habitual criminals commit crimes repeatedly and indifferently, viewing them as ordinary acts rather than moral failings.

-

Though not physically marked by congenital anomalies, long exposure to prison life produces visible changes — such as wrinkles, a hardened expression, tattoos, and a “shifty, sneaking look.”

-

They adopt criminal slang and habits, making them outwardly similar to born criminals, despite their different origins.

Penology:

-

Lombroso warned that short prison sentences for minor offenders could turn them into habitual criminals by exposing them to hardened inmates.

-

He also feared that giving them better education in prison might create more “educated recidivists.”

-

He advocated instead for alternative punishments such as fines, probation, or labour, aiming to prevent moral contamination.

4. Criminals by Passion

At the opposite end of the spectrum were Criminals by Passion, whom Lombroso regarded as the moral and emotional opposite of the born criminal.

He famously called them the “ultraviolet ray of the criminal spectrum” — a poetic way of saying that their crimes came from too much emotion, rather than too little.

Key Features:

-

Motivation: These individuals committed crimes from an excess of noble qualities — deep love, loyalty, compassion, patriotism, or honour. Their crimes were impulsive and unplanned, often provoked by strong moral or emotional drives.

-

Psychology: They lacked the laziness and selfishness typical of common offenders. Instead, they were highly sensitive and remorseful, often experiencing intense guilt or even suicidal despair after the act.

-

Physical Traits: Lombroso claimed they had attractive features and high foreheads, symbolising intelligence and sensitivity, in contrast to the coarser appearance of born criminals.

-

Types of Crime: Most crimes in this category involved homicide (about 91%), usually under emotional strain rather than malice. Lombroso also included political offenders, such as revolutionaries or reformers, whom he described as intelligent, idealistic, and guided by exaggerated moral ideals.

-

Punishment: He argued that exile — rather than imprisonment — was the most suitable punishment for political criminals, reflecting his belief that their motives were sincere but misplaced.

Lombroso’s Penological Recommendations

Lombroso’s understanding of occasional criminals led him to propose different types of punishment for them.

He believed that short prison sentences were harmful because they exposed minor offenders to hardened criminals, increasing their likelihood of reoffending.

Instead, he recommended alternative penalties such as:

-

Fines or restitution

-

Compulsory labour

-

Probation or supervision

-

Indeterminate sentences focused on rehabilitation rather than retribution

This reflected Lombroso’s gradual shift toward a more humane and preventive approach, recognising that environment, opportunity, and treatment played key roles in shaping behaviour.

The Female Offender

Lombroso also turned his attention to female criminality, publishing his findings in The Female Offender (1895).

He noted that women appeared less frequently in crime statistics than men, which he interpreted through a mix of biological and social reasoning.

Lombroso noted that women made up a small proportion of offenders — for example, 8–15% of serious crimes in countries like Italy, Spain, and Austria.

He believed this was because women were naturally less evolved toward crime due to their maternal instincts and social roles.

The “Double Exception” and Greater Ferocity:

While women were less likely to become criminals, Lombroso claimed that when they did, they were more dangerous and cruel than men.

-

He said normal women are restrained by “virtue,” “piety,” and maternal instincts.

-

If a woman became criminal, it meant these restraining influences had completely failed — so her wickedness must be extreme.

-

He described such women as “monsters,” capable of “refined cruelty” and revenge.

Prostitution as the Female Equivalent of Crime:

Lombroso argued that prostitution was the female form of criminality, since it satisfied the same immoral desires for idleness, pleasure, and indecency that led men to crime.

If prostitution were counted as a crime, Lombroso suggested that men and women would appear equally criminal.

The prostitute, in his view, was “the true representative of female criminality.”

Physical and Atavistic Traits:

Lombroso claimed that female offenders displayed masculine characteristics, both physically and behaviourally.

He described them as having projecting jaws, large ears, and coarser features, with deeper voices, different pelvic shapes, and abnormal hair growth patterns.

In his view, they lacked the gentleness and maternal instincts typical of “normal” women.

He also noted that most female offenders did not show as many physical “stigmata” as male criminals, suggesting they were closer to the average woman and more influenced by environment than biology.

Sentencing and Punishment:

Because women were seen as useful in domestic life, Lombroso suggested avoiding prison for female offenders when possible.

Instead, he proposed “moral punishments,” like cutting their hair or forcing them to wear a distinctive costume, appealing to their “vanity.”

He also called for special courts to deal with women’s cases.

Legacy of Cesare Lombroso

Cesare Lombroso’s legacy does not rest on the accuracy of his biological theories — most of which have been scientifically discredited — but on his revolutionary change in method.

He shifted the study of crime away from abstract legal philosophy toward empirical, evidence-based study of the offender.

For this reason, he is still widely recognized as the “father of modern criminology.”

Lombroso’s impact can be understood in three main areas:

-

His methodological shift in studying crime and criminals.

-

The creation of the Positive School of criminology.

-

His influence on penal reform and clinical criminology around the world.

1. A New Scientific Approach to Crime

Before Lombroso, criminology was mainly a branch of legal philosophy — focused on defining crimes and punishments rather than understanding offenders.

Lombroso changed this by insisting that crime should be studied scientifically, like a medical or psychological condition.

Studying the Criminal, Not the Crime

Lombroso was the first to argue that criminology should focus on the criminal, not the crime.

Instead of asking “What law was broken?”, he asked “Who is the person who breaks it, and why?”

This represented a major paradigm shift, moving criminology toward the study of individual differences, personality, and behaviour.

Influenced by Auguste Comte’s positivism, Lombroso relied on observation, measurement, and data collection rather than abstract reasoning.

He conducted anthropometric (body measurement) studies, clinical examinations, and post-mortems, seeking “positive facts” to explain criminal behaviour.

Recognizing Social and Environmental Factors

Although best known for his theory of the “born criminal,” Lombroso’s later work became more balanced and multidimensional.

He began to acknowledge that social and environmental conditions also shape criminal behaviour.

He wrote about the interaction between heredity and environment, identifying factors such as:

-

Poverty and hunger

-

Rising food prices

-

Alcoholism

-

Migration and urban crowding

-

Criminal gangs and poor social environments

In this sense, Lombroso evolved from strict biological determinism toward a more holistic view that combined biology, psychology, and sociology.

2. The Rise of the Positive School

Lombroso’s work laid the foundation for the Positive School of Criminology, also known as the Modern Italian School.

This new school of thought rejected the Classical idea of free will and moral responsibility and replaced it with a focus on determinism — the belief that behaviour is shaped by internal and external forces.

The Spread of Lombroso’s Ideas

Lombroso’s ideas quickly spread through Europe and the Americas by the late 19th century, largely due to his influence on his Italian followers:

-

Enrico Ferri, who combined Lombroso’s biological ideas with sociological theory, emphasizing social and economic causes of crime.

-

Raffaele Garofalo, who helped develop criminal law reforms based on Lombroso’s principles.

Together, these thinkers transformed Lombroso’s work into a coherent school of thought that profoundly influenced criminological research and legal reform.

3. Influence on Penology and Treatment

The deterministic nature of Lombroso’s theories — the belief that individuals are shaped by forces beyond their control — led to progressive reforms in how criminals were punished and treated.

From Punishment to Prevention

Lombroso’s followers argued that the justice system should focus on social defence (protecting society) rather than moral retribution.

Instead of treating all offenders the same, they promoted individualized sentencing — taking into account the offender’s personality, background, and potential for rehabilitation.

The aim was not just to punish but to understand, classify, and treat the offender.

This gave rise to reforms such as:

-

The indeterminate sentence (release based on behaviour and rehabilitation, not fixed time).

-

Probation and parole systems.

-

Juvenile courts, which recognized that children should be treated differently from adults.

-

The development of reformatories, such as the famous Elmira Reformatory in the United States.

Lombroso also emphasized the role of early prevention, calling for institutions to help “prevent crime from the cradle” through education and social support.

Continuing Influence: Clinical Criminology in Italy

Even after Lombroso’s theories were challenged, his methods inspired a new generation of clinical criminologists in Italy, who viewed criminal behaviour through medical and psychological lenses.

-

Benigno Di Tullio, one of Lombroso’s intellectual heirs, developed the typological-constitutionalist method, which linked personality and biological constitution to crime.

-

This approach combined psychological assessment and medical examination to better understand offenders and design treatment plans.

Modern Italian criminology, though far more advanced, continues this individualized and clinical focus, using scientific methods to study offenders rather than relying solely on moral or legal definitions.

Global Influence on Penal Reform

Lombroso’s legacy extended far beyond Italy. His emphasis on understanding and rehabilitating offenders influenced criminal justice systems across the world, particularly in:

-

The United States, where reformers used positivist ideas to develop the probation system, juvenile courts, and rehabilitative prisons.

-

Europe, where individualized sentencing and psychiatric evaluations became central to modern penal practice.

Although later critics — such as Charles Goring — showed that Lombroso’s biological conclusions were scientifically unsound, his methodological revolution permanently changed the study of crime.

He transformed criminology into a scientific discipline, influencing fields as diverse as psychology, psychiatry, and sociology.

Critical Evaluation

Although Cesare Lombroso is often called the “father of modern criminology,” his theories faced widespread criticism for serious flaws in both method and reasoning.

His claim that criminality was largely determined by biological and physical traits sparked decades of debate and was eventually discredited by later research.

Lombroso’s work is best understood as a scientific turning point rather than a lasting truth — a bold but flawed attempt to explain crime through science.

His limitations fall into three key areas: methodological weaknesses, theoretical problems, and bias in scope and assumptions.

1. Methodological and Statistical Problems

Lombroso aimed to apply scientific methods to the study of crime, but his approach suffered from serious weaknesses in measurement, sampling, and analysis.

Lack of Control Groups

The most serious flaw in Lombroso’s work was his failure to use proper control groups — a cornerstone of scientific research.

-

He compared criminals to groups such as “non-criminal Italian soldiers” or “normal women,” but these samples were not representative of the general population.

-

Without reliable comparison groups, Lombroso’s conclusions about what made criminals “different” were meaningless — the entire foundation of his theory could collapse.

Imprecise and Subjective Measurement

Lombroso’s measurements of physical traits were often inaccurate and inconsistent, undermining his scientific credibility.

-

His anthropometric data (e.g., skull and facial measurements) were often taken with little precision or standardization.

-

Rather than using objective statistics, he often relied on subjective observations, describing traits like “facial asymmetry” without consistent criteria.

-

Critics argued that his findings were shaped by his personal bias — he tended to “find” what his theory predicted.

-

He also relied on second-hand data from students and assistants, often without checking accuracy, further weakening his results.

Unreliable Reasoning and Presentation

Lombroso’s analytical style mixed scientific data with anecdote, analogy, and assumption.

-

He frequently used anecdotal evidence or intuitive analogies, mistaking resemblance for proof. For instance, he drew far-fetched connections between “genius and republicanism” or between criminality and epilepsy.

-

His reasoning was often circular: he started with a belief (that criminals were biologically different) and then looked for physical traits to confirm it.

-

Later critics said his conclusions rested not on evidence but on a “leap of imagination” — the opposite of the objective positivism he claimed to practice.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Limitations

Even apart from weak data, Lombroso’s central ideas were internally inconsistent and conceptually rigid.

Biological Determinism and Reductionism

Lombroso claimed that crime could be explained primarily by biology, but this monogenetic determinism (the idea that one main cause explains everything) clashed with his later recognition that multiple causes were involved.

-

He never truly gave up his belief in the “born criminal.” Even in his final works, he estimated that around one-third of offenders were biologically predisposed to crime.

-

When he did discuss environmental influences (such as poverty or alcohol), he tended to reduce them to biology, suggesting that external conditions could become “organic” — that is, physically embedded in the person.

-

His failure to define how many physical or mental “anomalies” were needed to qualify someone as a born criminal left his theory vague and untestable.

Contradictions: Atavism vs. Degeneration

Lombroso’s attempts to merge two conflicting ideas — atavism (reversion to a primitive evolutionary type) and degeneration (a diseased, weakened state) — made his theory incoherent.

-

Biologists of the time pointed out that the two ideas contradict each other: one implies a return to strength, the other to decay.

-

Lombroso’s effort to explain crime through both concepts at once made his biological model internally inconsistent.

-

He was also accused of tautology — defining criminals by the traits that supposedly proved their criminality, after the fact. In other words, someone was a criminal because they had certain traits, and those traits were “criminal” because criminals had them.

3. Bias and Narrow Scope

Lombroso’s work reflected the biases and assumptions of his era, which limited both its scope and fairness.

Static and One-Dimensional View of Crime

Lombroso treated criminality as a fixed trait, visible in physical form, rather than a behaviour that develops through social and psychological processes.

-

His studies focused on permanent features (like skull shape or facial structure), ignoring situational or social factors.

-

He overlooked the idea that crime could result from circumstances, opportunity, or environment — a view that later became central to sociology and psychology.

Ignoring Statistical and Sociological Research

While Lombroso sought to establish criminology as a science, he neglected existing statistical work by early social scientists like Guerry and Quetelet, who had already demonstrated the importance of social factors in crime patterns.

He later acknowledged them only after critics pointed out the omission.

Gender Bias and Misrepresentation

Lombroso’s treatment of women in The Female Offender (1893) revealed deep gender bias.

-

He argued that women were naturally less criminal but, when they did offend, were more wicked and dangerous than men.

-

He equated prostitution with female criminality, claiming that it satisfied the same immoral instincts as male crime.

-

He described female born criminals as monstrous, masculine, and emotionally deficient, echoing the sexist assumptions of his time rather than scientific reasoning.

Historical Impact

Even sympathetic critics later argued that Lombroso’s school set back criminological progress by decades.

American criminologists Sutherland and Cressey claimed that Lombroso and his followers “delayed for fifty years the work which was already in progress” — by focusing on measurement and anomalies instead of developing true social science.

Summary

Lombroso’s work represents both a breakthrough and a blind alley in criminology.

He was the first to insist that crime could be studied scientifically, but his methods and assumptions were deeply flawed.

| Type of Limitation | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological | Weak data collection and lack of control groups undermined his “scientific” claims. | Relied on subjective measurements and biased samples. |

| Theoretical | Contradictory ideas and overreliance on biology made his theory incoherent. | Tried to combine atavism (primitive) with degeneration (diseased). |

| Cultural and Gender Bias | Reflected 19th-century prejudices rather than objective science. | Claimed women’s crime was equivalent to prostitution. |

Despite its flaws, Lombroso’s work transformed the study of crime.

His attempt to treat criminality as a subject for science, not philosophy, laid the foundation for later, more rigorous research in psychology, sociology, and forensic science.

Biography

Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was an Italian doctor and researcher who helped lay the foundations for modern criminology — the scientific study of crime and criminals.

His career combined medicine, anthropology, and psychiatry, and he was one of the first to suggest that criminal behavior could have biological roots.

Early Life and Education

Lombroso was born on November 6, 1835, in Verona, Italy, into a Jewish family.

His mother, Zefira Levi Lombroso, was ambitious for her children’s education, and young Cesare was able to attend a Jesuit school — unusual for a Jewish boy at the time.

He showed academic talent early on:

-

At 15, he wrote essays on Roman history and ancient agriculture.

-

At 18, he became interested in medicine, inspired by the philosopher and doctor Paolo Marzolo.

Lombroso studied at several universities across Europe:

-

University of Pavia (1852–1854) – earned his medical degree in 1858.

-

University of Padova (1854–1855)

-

University of Vienna (1855–1856)

-

University of Genoa (1859) – earned a degree in surgery.

His first major research, on cretinism (a developmental condition caused by iodine deficiency), became his doctoral thesis in 1859.

Career and Professional Roles

Lombroso’s career combined medicine, psychiatry, and criminology. Over the years, he worked as:

-

Army Doctor (1859–1863) – Served in Calabria, studying and measuring 3,000 soldiers. This gave him experience observing human variation and behavior firsthand.

-

Psychiatrist – Directed hospitals for the mentally ill in Pavia, Pesaro, and Reggio Emilia, and began teaching psychiatry and anthropology.

-

Professor – Taught at the University of Turin, where he became:

-

Professor of Legal Medicine (1876)

-

Professor of Psychiatry (1896)

-

Professor of Criminal Anthropology (1906)

-

-

Criminologist – Founded the journal Archivio di Psichiatria e Antropologia criminale (1880) and the Museum of Criminal Anthropology in Turin (1906).

-

Public Official – Served as a municipal councilor for a working-class district in Turin.

Influences and Key Ideas

Lombroso’s thinking was shaped by the scientific and philosophical movements of his time.

He rejected the idea that people freely choose to commit crimes (as earlier thinkers claimed) and instead focused on the biological and psychological traits of offenders.

His ideas were influenced by:

-

Darwin’s theory of evolution

-

Auguste Comte’s positivism (the belief that human behavior can be studied scientifically)

-

Haeckel’s recapitulation theory, which suggested that development repeats stages of evolution

How He Developed His Theories

Lombroso’s most famous idea — the theory of the “born criminal” — developed gradually from his medical observations:

-

Studies on Pellagra and Cretinism: While researching these diseases in Northern Italy, he noticed how malnutrition and illness could cause mental and behavioral problems, sometimes even violent behavior.

-

Military Observations (1864): As an army doctor, he compared disciplined soldiers with those who caused trouble, noticing that the latter often had extensive tattoos and distinctive physical traits.

-

The Vilella Postmortem: While performing an autopsy on a notorious criminal named Vilella, Lombroso found an unusual hollow in the skull (the median occipital fossa). He interpreted this as evidence of atavism — a throwback to primitive human ancestors.

-

The Misdea Case: The case of Misdea, an epileptic soldier who killed several people during a seizure, led Lombroso to link some types of crime with epilepsy and brain dysfunction.

From these experiences, Lombroso concluded that some criminals were biologically predisposed to crime — that they represented an earlier stage of human evolution.

References

Beirne, P. (1987). Between Classicism and Positivism: Crime and Penality in the Nineteenth Century. In M. Fitzgerald, G. McLennan, & J. Pawson (Eds.), Crime and Society: Readings in History and Theory (pp. 45–70). Routledge.

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (Eds.). (2018). Criminological Theory: Past to Present (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

DeLisi, M. (2012). Criminology: A Contemporary Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ferri, E. (1917). Criminal Sociology (J. I. Kelley, Trans.). D. Appleton and Company. (Original work published 1884)

Goring, C. (1913). The English Convict: A Statistical Study. His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Lombroso, C. (1876). L’Uomo delinquente [The Criminal Man]. Hoepli.

Lombroso, C., & Ferrero, G. (1895). The Female Offender. Appleton and Company.

Rafter, N. (2008). The Criminal Brain: Understanding Biological Theories of Crime. New York University Press.

Rafter, N., & Gibson, M. (Eds.). (2004). Criminal Man (M. Gibson & N. Rafter, Trans.). Duke University Press. (Original work published 1876)

Sutherland, E. H., & Cressey, D. R. (1978). Criminology (10th ed.). Lippincott.

Taylor, I., Walton, P., & Young, J. (1973). The New Criminology: For a Social Theory of Deviance. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Wolfgang, M. E., & Ferracuti, F. (1967). The Subculture of Violence: Towards an Integrated Theory in Criminology. Tavistock Publications.