Everyone experiences anxiety at times. Your nervous system activates the fight-or-flight response based on perceived threats, but sometimes, it misreads harmless situations as dangerous.

When your body reacts strongly, yet you can’t pinpoint an obvious trigger, it may seem like anxiety has arisen randomly.

In reality, there is usually a reason why you are anxious, even if you cannot determine what it is. Subtle factors like genetics, past traumas, medications, or physical health issues could be sparking symptoms.

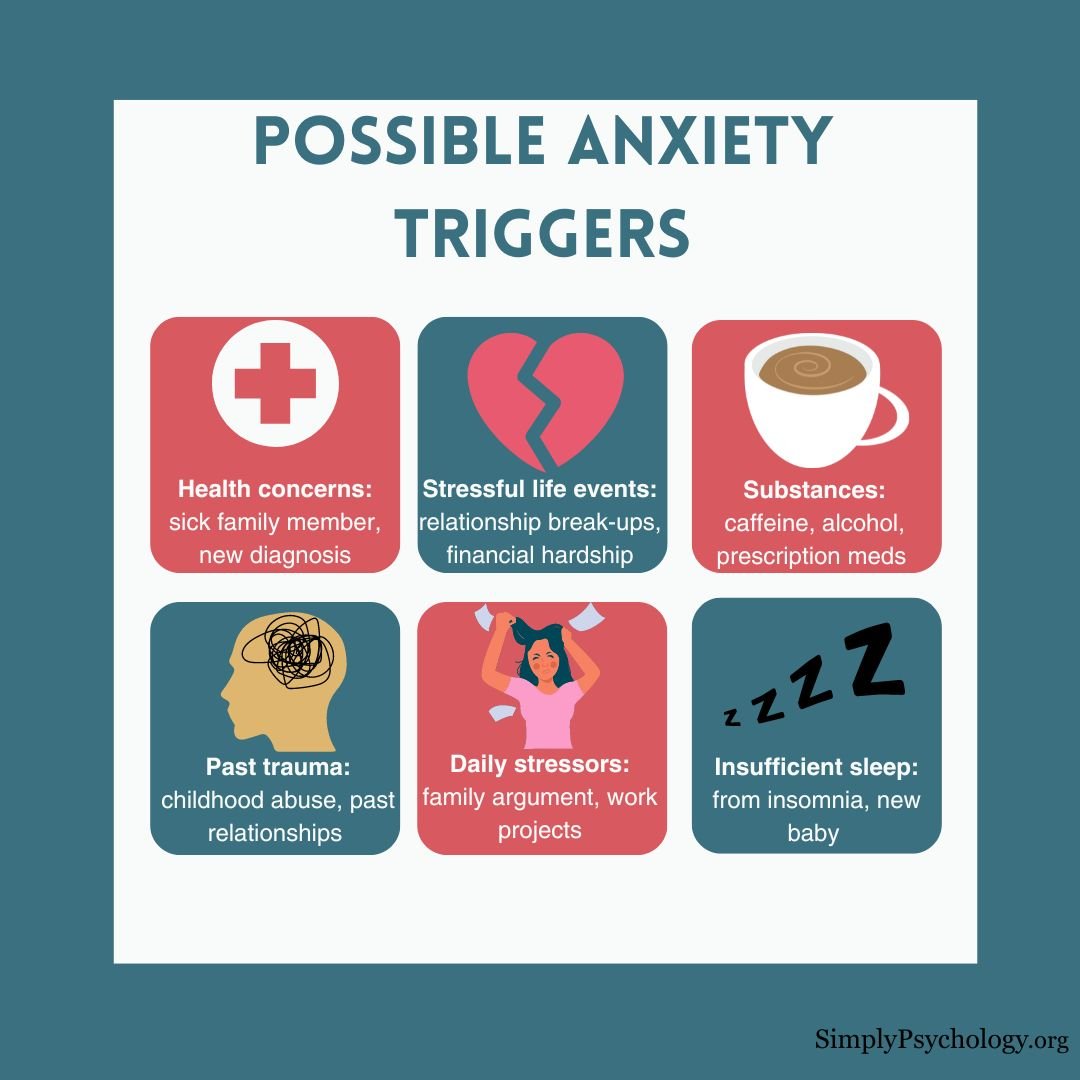

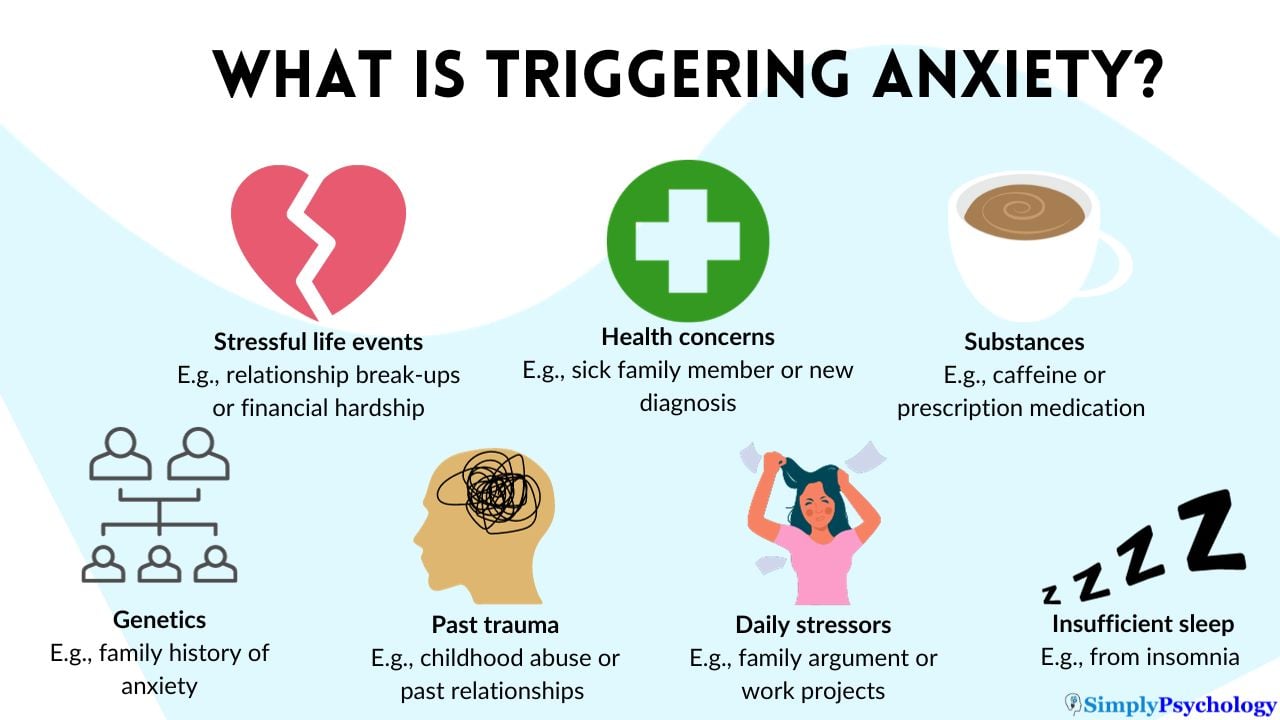

What are some common anxiety triggers?

Anxiety triggers can vary significantly among individuals, and many people may have multiple triggers that provoke different degrees of anxiety.

However, research has identified some frequent triggers that commonly spur anxiety symptoms:

- Stressful life events – Events like losing a job, financial hardship, relationship problems, or other difficult life changes can trigger anxiety by causing uncertainty and upheaval. A 2009 study found that stressors such as health and family fall-outs predicted increases in anxiety sensitivity (McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

- Medical conditions – Chronic health issues, such as thyroid disorders, heart problems, or asthma, can worsen anxiety. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, signs of anxiety can be aggravated by some physical health conditions (NIMH, 2023).

- Medications – Substances like caffeine, nicotine, recreational drugs, and certain prescription medications may provoke anxiety as a side effect. A 2022 study found that a dose of roughly 5 cups of coffee induced panic attacks in many people with panic disorder, as well as higher anxiety levels in these individuals (Klevebrant & Frick, 2022).

- Genetics – Having a family history of anxiety disorders increases genetic risk. A meta-analysis found anxiety disorders had an estimated heritability of around 30% to 50% (Hettema et al. 2001).

- Trauma – Past traumatic experiences can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), causing anxiety and panic attacks when triggered. Childhood trauma specifically elevates anxiety disorder risk later in life, according to a 2021 review (Kuzminskaite et al. 2021).

- Chronic stress – Daily stressors and worry about work, relationships, finances, and other issues can sustain high anxiety levels. A 2017 study found that repeated exposure to short-term stressors can lead to maladaptive stress responses, increasing the risk for anxiety disorders (Patriquin & Mathew, 2017).

- Insufficient sleep – Lack of quality sleep deprives the body of vital recovery and rejuvenation needed to regulate anxiety levels. A 2016 systematic review noted insufficient sleep duration significantly increased anxiety risk (Pires et al. 2016).

Identifying individual triggers through methods like journaling can help pinpoint the causes of anxiety.

Discussing patterns with a mental health professional can also provide insight into personalized triggers and effective coping strategies.

It can be important to find out what is causing you anxiety as this is an important step in managing it.

How Can You Identify Anxiety Triggers?

A useful way of identifying triggers of anxiety can be to start a journal. This can be used to document your moods each day and see if any patterns of anxiety emerge.

If patterns are noticed, it can be easier to pinpoint what may be causing the anxiety.

If you find it challenging to identify triggers and your anxiety is causing you distress, you can work with a therapist to help explore what may be causing your anxiety.

A specialist may use talk therapy, among other methods, to help find the causes of your anxious feelings.

“Alex started experiencing anxiety seemingly out of nowhere. He couldn’t identify a specific reason why his heart raced or why he felt tense in everyday situations. After speaking with a therapist, Alex realized that the anniversary of a past car accident—which he consciously hadn’t thought about—was subtly triggering his nervous system, causing anxiety without an obvious current event.”

Is Some Anxiety Normal?

Anxiety is a normal human reaction to many situations, especially in times of stress. It is also normal to want to get rid of anxiety altogether since it feels uncomfortable.

However, getting rid of anxiety can be counterproductive, and it can make people more anxious.

Having some anxiety shouldn’t be seen as something threatening at all. In fact, having some anxiety can be useful.

Having anxious feelings may stop people from engaging in risky behaviors as well as giving someone an idea about how they feel about certain situations.

For instance, if you are nervous about attending a job interview or going on a first date, this may give you an indication that these experiences are important to you.

If you do not feel some anxiety before a first date, you may not feel obliged to make an effort with the other person.

Likewise, some anxiety before a job interview might make you more alert and improve your performance.

However, for some people, this kind of anxiety operates beneath the surface — they appear calm and capable while still feeling overwhelmed inside, a pattern often described as high-functioning anxiety.

What Is Free-Floating Anxiety?

Free-floating anxiety describes feelings of discomfort, uneasiness, worry, and anxiety that can appear for seemingly no reason.

Many times, this anxiety can feel generalized or even random and does not appear to be tied to any particular object or situation.

Free-floating anxiety can be experienced by those with anxiety disorders and those without.

Some people can experience free-floating anxiety even when they believe things are going really well in all aspects of their life.

People with free-floating anxiety can spend so much time preoccupied with these general feelings of unease and worry that they have a difficult time enjoying their lives and experience lower levels of overall life enjoyment and happiness.

Feelings of this anxiety can also contribute to other problems such as depression, headaches, social withdrawal, substance misuse, and relationship problems.

Recognizing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

While free-floating anxiety refers to occasional, generalized anxiety without clear triggers, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is a clinical condition characterized by persistent, excessive anxiety and worry about various aspects of daily life, such as work, relationships, health, or finances.

You may be experiencing GAD if:

- Your anxiety and worry have been occurring for at least six months.

- You find it very difficult to control or manage these anxious feelings.

- Your anxiety significantly impacts your daily activities, relationships, or job performance.

Additionally, GAD often comes with several physical and psychological symptoms, including:

- Feeling restless, irritable, or on edge

- Frequent fatigue or exhaustion

- Difficulty concentrating or your mind going blank

- Muscle tension, aches, or soreness

- Sleep disturbances such as trouble falling asleep or staying asleep

In contrast, normal or occasional free-floating anxiety typically doesn’t persist for extended periods, is easier to manage, and doesn’t significantly disrupt daily activities.

If your anxiety resembles GAD more closely than typical anxiety, seeking guidance from a mental health professional is advisable.

“Maria always felt a bit nervous before exams, which was normal and manageable. However, over the last six months, her anxiety expanded into constant worries about school, relationships, and even routine activities like grocery shopping. These worries persisted despite nothing obviously being wrong, significantly disrupting her daily life. Recognizing these symptoms, Maria reached out to a mental health professional and learned she was experiencing symptoms consistent with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.”

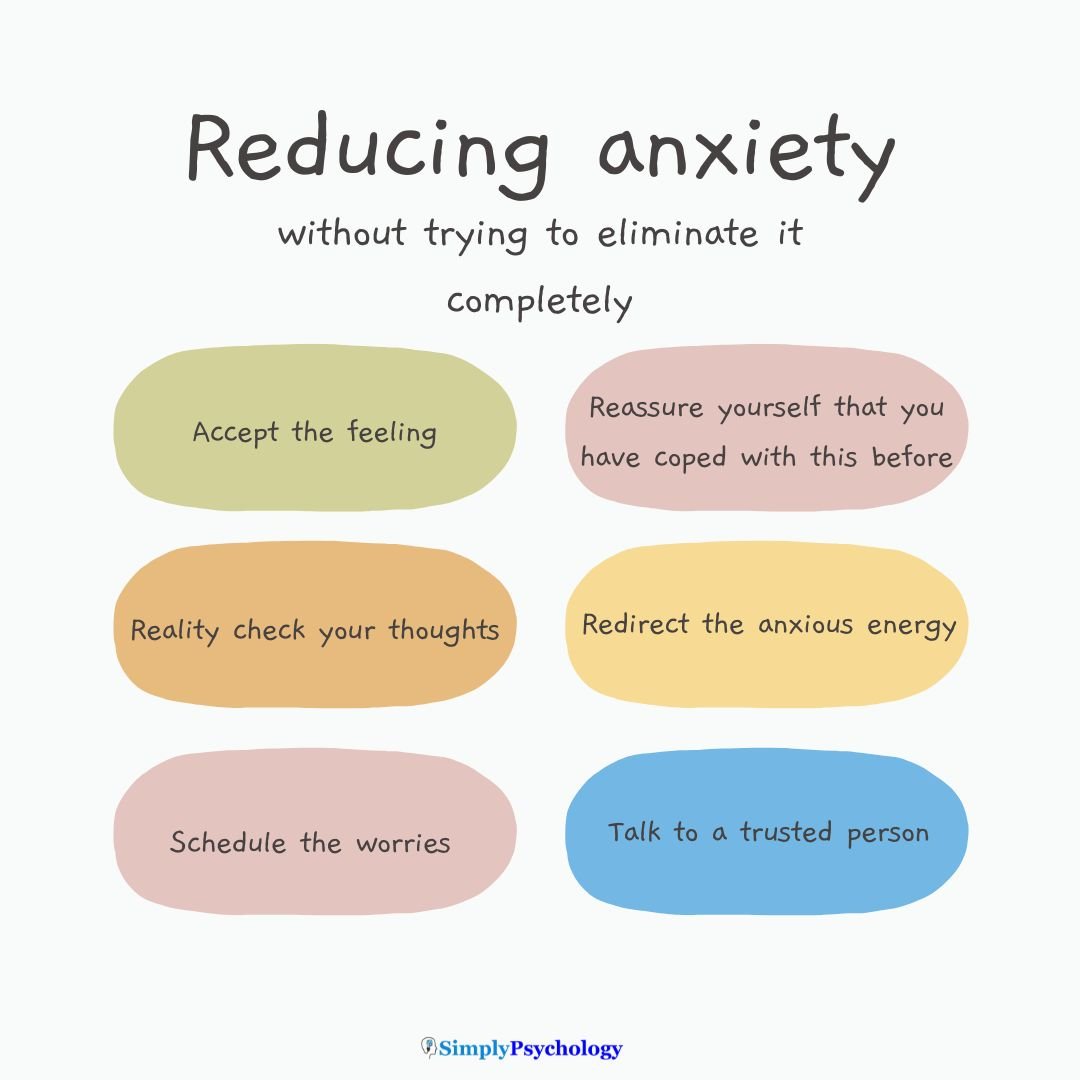

How To Reduce Anxiety

While we may feel inclined to want to stop all feelings of anxiety, it is important to remember that some anxiety is normal and helpful in certain situations.

Trying to stop anxious feelings is a form of resistance and can, in fact, make anxiety stronger. This relates to ironic processing theory, which explains why it is so hard to decrease unwanted thoughts.

The theory states that when we try not to think of something, such as being anxious, this will only lead to thinking more about being anxious, which leads to more anxiety.

When we try not to think of something, one part of our mind avoids the thought, but another part ‘checks in’ every so often to ensure the thought is not coming up – ironically, bringing it to mind.

If your only strategy is to distract yourself from the anxiety or to avoid anything that may trigger it, you are likely to always be afraid of it, and this can contribute to the vicious cycle of anxiety.

Instead, you could try some of the following methods to ease some of your anxiety:

Accept the feeling and don’t try to ‘fix it’

One of the most effective ways to ease anxiety is to accept it when the feeling comes. When the anxiety is allowed to run its course in the moment, without trying to resist it, it should eventually reduce.

Cherelle Roberts, a Health Anxiety Therapist, explains one of the main ways to deal with anxiety that we cannot always control:

“The biggest thing of all is we learn to sit and wait and deal with the uncertainty… You have to work on your impulsive need to problem-solve”

Recognizing and understanding where the anxiety is coming from can also be helpful.

For instance, you could say to yourself:

- ‘My nervous system is getting into gear because I am worried about a social event.’ or

- ‘I am feeling anxious about the health of my loved one. This is a normal response. There is nothing that I, specifically, can do to fix it, but I can offer my support in other ways.’

Give yourself reassurance

When you start to feel anxious, remind yourself, “I have coped with anxiety successfully in the past, and I can handle this, too.”

Reassure yourself that if you could survive those past anxious episodes, you have evidence this current anxiety won’t overwhelm you either.

Visualize yourself coping well in the situation causing you anxiety. Recall the relief you felt afterwards too – anxiety is temporary and fades. Reassure yourself that you can navigate this anxiety as well; it will pass. Self-compassion is key.

Reality check

It is useful to challenge your anxious thoughts when they emerge. You can ask yourself the following questions:

- ‘On a scale of 1-100, how likely is it that the thing I am anxious about will happen?’;

- ‘Do I have good reason to think that something will go wrong?’;

- ‘Is there any actual danger here?’;

- ‘Is there a chance I am overly worried?’

Talk to someone you trust

It can help to share your anxieties with a friend or family member that you trust.

Another person can help to put everything into perspective and help you to challenge your anxious thoughts if you struggle to do this on your own.

Redirect anxious energy

Anxiety creates an excess of nervous energy in the body. When you start to feel particularly anxious or antsy, try redirecting that energy into productive activities.

Going for a brisk walk, jogging, or engaging in other cardiovascular exercises can help metabolize the adrenaline and cortisol flooding your system. The aerobic activity burns through the hormones, exacerbating your anxiety.

You could also channel nervous energy by tackling a long-put-off cleaning project at home. Scrub the floors, organize cluttered spaces, or polish furniture. The physical motions can provide an outlet for anxiety while also giving you a sense of accomplishment afterward.

Schedule the worries

It may be useful to schedule a small portion of time in the day dedicated to allowing your ‘worry time’.

For instance, you could schedule to worry for 15 minutes at 4 pm, but if the anxious thoughts come outside of this time, gently tell the thoughts to come back at another scheduled time.

You may find that by the time your worry time comes, you are not so anxious anymore; it was not worth the time to worry about, or you forgot about it completely.

Meditation and mindfulness

Relaxation exercises such as meditation and mindfulness can be useful for helping to notice anxious thoughts and any other physical sensations and where they may be coming from.

Mindfulness practice involves paying attention to the present moment with openness, curiosity, and non-judgment, allowing for greater awareness and acceptance of one’s thoughts, feelings, and surroundings.

There is evidence that these practices can strengthen mental control and may help people avoid unwanted thoughts.

When does anxiety need treatment?

Although anxiety is normal, if it gets to a point where it feels like it is getting out of hand and you have been unsuccessful in trying to decrease it yourself, it may be time to seek help.

Some other signs that may indicate that you may need treatment:

- Constant or nearly constant anxiety

- The anxiety is disrupting your normal daily functioning

- Anxiety about things that don’t threaten you

- You are experiencing panic attacks

- Complications occur in other aspects of life, such as substance abuse, isolation, breakdowns in relationships, and struggling at school or work.

Professional treatment available for anxiety that is constantly interfering in all or most aspects of life includes psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy) and medications (e.g., SSRIs or benzodiazepines).

Do you need mental health support?

USA

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

References

Government of Western Australia. (n.d.). The Vicious Cycle of Anxiety. Centre for Clinical Interventions. Retrieved 2021, October 12, from: https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/CCI/Mental-Health-Professionals/Panic/Panic—Information-Sheets/Panic-Information-Sheet—03—The-Vicious-Cycle-of-Anxiety.pdf

Gregory, K. D., Chelmow, D., Nelson, H. D., Van Niel, M. S., Conry, J. A., Garcia, F., Kendig, S. M., O’Reilly, N. Qaseem, A., Ramos, D., Salganicoff, A., Son, S., Wood, J. K. & Zahn, C. (2020). Screening for anxiety in adolescent and adult women: a recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(1), 48-56.

Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. American journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1568-1578.

Kuzminskaite, E., Penninx, B. W., van Harmelen, A. L., Elzinga, B. M., Hovens, J. G., & Vinkers, C. H. (2021). Childhood trauma in adult depressive and anxiety disorders: an integrated review on psychological and biological mechanisms in the NESDA cohort. Journal of affective disorders, 283, 179-191.

Klevebrant, L., & Frick, A. (2022). Effects of caffeine on anxiety and panic attacks in patients with panic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 74, 22-31.

Lieb, R., Becker, E., & Altamura, C. (2005). The epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Europe. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(4), 445-452.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of abnormal psychology, 118(3), 659.

Monk, C. S., Telzer, E. H., Mogg, K., Bradley, B. P., Mai, X., Louro, H. M., Chen, G., McClure-Tone, E. B., Ernst, M. & Pine, D. S. (2008). Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 65(5), 568-576.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Anxiety Disorders. Retrieved November 20, 2023, from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders

Nikčević, A. V., Marino, C., Kolubinski, D. C., Leach, D., & Spada, M. M. (2021). Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 578-584.

Patriquin, M. A., & Mathew, S. J. (2017). The neurobiological mechanisms of generalized anxiety disorder and chronic stress. Chronic Stress, 1, 2470547017703993.

Sanderson, W. C., Wetzler, S., Beck, A. T., & Betz, F. (1994). Prevalence of personality disorders among patients with anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research, 51(2), 167-174.

Tyrer, P., & Baldwin, D. (2006). Generalised anxiety disorder. The Lancet, 368(9553), 2156-2166.

Winerman, L. (2011, October). Suppressing the ‘white bears’. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/10/unwanted-thoughts