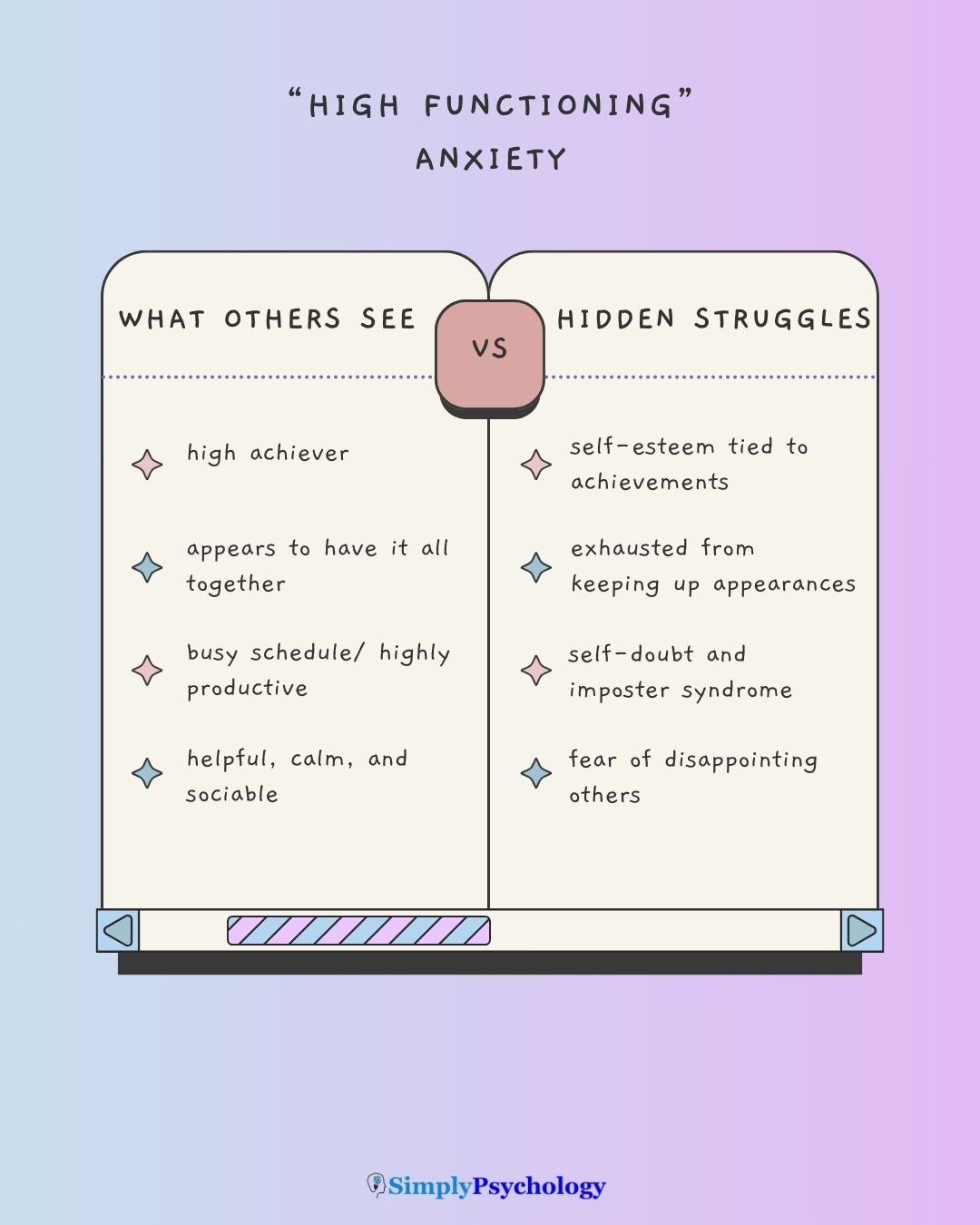

High-functioning anxiety describes people who appear confident, organized, and successful on the outside but struggle with worry, self-doubt, and restlessness on the inside.

Unlike stereotypical images of anxiety—panic attacks or visible distress—those with high-functioning anxiety often mask their struggles behind productivity, perfectionism, or an outgoing personality.

This can make their anxiety difficult for others to recognize, and even harder for them to acknowledge in themselves.

How Is It Different From Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

While high-functioning anxiety shares many features with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)—such as excessive worry, overthinking, and physical tension—there are some differences:

- GAD: Anxiety symptoms often interfere with daily functioning. People may avoid responsibilities, social activities, or work due to overwhelming fear or stress.

- High-Functioning Anxiety: Symptoms are present but hidden. Anxiety may actually fuel achievement, leading to outward success in academics, career, or relationships—while inner distress remains constant.

In short, GAD is clinically recognized and typically impairs daily functioning, while high-functioning anxiety describes a pattern where anxiety coexists with apparent success.

Is High-Functioning Anxiety an Official Diagnosis?

No. High-functioning anxiety is not a formal diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Instead, it’s an informal term used to capture a real experience: people who meet expectations externally but struggle internally with persistent anxiety.

Because it’s not an official diagnosis, it may overlap with GAD or other anxiety disorders, but it resonates with many people who feel their anxiety is “invisible” or dismissed because they appear to cope well.

The Problem With the Term ‘High Functioning’

While reading this article, it is important to keep in mind that the term ‘high functioning’ can be problematic. Below are some reasons why the term ‘high functioning anxiety’ comes with issues.

It minimizes the struggles people face

Firstly, the term ‘high functioning anxiety‘ suggests that anxiety is a positive thing that can help people perform better, which is not necessarily true.

While some anxiety can motivate people to work harder or be more productive, it can also be overwhelming, debilitating, and harmful to one’s mental health.

Just because someone with anxiety can ‘function’ well in many areas of life, does not mean they do not struggle in other areas.

It implies that some types of anxiety are desirable

The term ‘high functioning anxiety’ implies that there is a hierarchy of anxiety disorders, with high-functioning anxiety being somehow better or more desirable than other forms of anxiety.

This can lead to a lack of understanding for those with different types of anxiety and can contribute to stigma and shame around seeking help for anxiety.

It pressures others to be as ‘successful’

The term ‘high-functioning’ is often used to describe people who can maintain a certain level of productivity or success despite their mental health struggles.

While it’s important to acknowledge and support people who can function well despite their anxiety, this term can also perpetuate the idea that people with mental health challenges need to constantly “prove” their worth or value.

High functioning = contributing to society

Often, people are described as having ‘high functioning anxiety’ if they are contributing to society, such as being successful at work.

The term suggests that their anxiety is positive because it propels them to perform well at work and be productive to society.

This narrow focus can create pressure for individuals to prioritize work over their mental health and can perpetuate the idea that one’s worth is based solely on their ability to perform well in their job.

Signs of High-Functioning Anxiety

These are the signs of high-functioning anxiety, as identified by Dr. Julie Smith, a clinical psychologist:

- You experience high anxiety levels, but that feeling drives you forward. Therefore, you still meet everyone’s expectations, and they are unaware of the intense fear you often experience.

- You function really well in day-to-day life. The problem arises when you have to slow down or stop and rest. Among your friends, you might be known as a workaholic.

- You appear calm on the outside, but you’re constantly worrying and doubting yourself on the inside.

Below are some additional signs that may indicate that someone has high-functioning anxiety:

Internal Signs (What It Feels Like)

- Excessive worry that never switches off – even when everything is going well.

- Self-doubt and fear of failure – achievements rarely feel “enough.”

- Restlessness and racing thoughts – difficulty relaxing or being present.

- Guilt when not being productive – downtime feels undeserved.

“It truly is a special kind of curse. I’ve always suffered with poor mental health… I learned to keep it to myself.”

This quote encapsulates the exhausting internal battle people with high-functioning anxiety often face—persistent self-pressure and hidden turmoil.

“I have a full and fun social life, a fantastic job and crippling high functioning anxiety… underneath all this self doubt, I was desperately sad… everyone always told me I was happy… I convinced myself I was OK because everyone saw me that way.”

This reflects the internal struggle to maintain a put-together persona while grappling with deep sadness and self-doubt.

External Signs (What Others See)

- High achievement – consistently meeting or exceeding expectations.

- Perfectionism – spending excessive time planning, preparing, or double-checking.

- Always busy – overcommitting to tasks, often at the expense of rest.

- Sociability and people-pleasing – eager to help others, even when overwhelmed.

- Outward calmness – appearing relaxed while concealing inner tension.

“I saw three or four therapists who told me, ‘wow, sounds like you’re doing really well!’ before seeing one who took my anxiety seriously.”

This quote illustrates how external success can obscure internal suffering, even in therapeutic contexts.

“It truly is a special kind of curse… I am able to get up, go to work, wear a smile… while concealing what I’m really going through.”

This highlights how the outwardly capable individuals hide a pervasive inner struggle, often unseen by friends, family, and professionals.

The Consequences of High-Functioning Anxiety

Although people with high-functioning anxiety may look confident and accomplished, their success is often driven by constant worry and self-pressure. Over time, this hidden struggle can take a significant toll.

- Overthinking and sleep problems: Racing thoughts, rumination, and the inability to “switch off” often lead to insomnia, restless nights, and fatigue.

- People-pleasing: Fear of letting others down pushes many to overcommit, avoid saying no, or even go to work sick rather than disappoint.

- Inability to relax: Downtime feels uncomfortable or “wasted,” leaving people restless, guilty, or dependent on nervous habits like nail-biting or pacing.

- High expectations and pressure to achieve: Internal and external demands create a cycle of perfectionism, burnout, and never feeling “good enough.”

- False persona and low self-esteem: Outward calmness or positivity often masks feelings of inadequacy, with self-worth tied only to achievements.

- Missed opportunities: Anxiety keeps people within their comfort zone, limiting experiences outside work or study.

- Unhelpful coping strategies: To manage the tension, some turn to alcohol, drugs, or other unhealthy habits.

What Causes High-Functioning Anxiety?

While there is often not one known cause for why someone may develop anxiety, it is thought that, in most cases, a combination of genetic and environmental factors can play a part.

Genetics

Someone may have a strong biological disposition to developing high-functioning anxiety, especially if they have an immediate relative, such as a parent, who also has anxiety or another mental health disorder.

Personality

Certain temperaments—such as being shy, cautious, or risk-averse in childhood—can increase the likelihood of developing anxiety later in life.

Traits like perfectionism, a strong need for control, or fear of failure can also set the stage for high-functioning anxiety.

Upbringing and family roles

Childhood experiences often play a key role. Growing up in an unpredictable or critical environment, or taking on adult responsibilities early—such as being the “responsible eldest child”—may teach a child to equate worth with achievement.

This can fuel over-responsibility, people-pleasing, and self-pressure in adulthood.

Negative experiences

Trauma, neglect, or exposure to family mental health struggles may also contribute, creating long-term patterns of hypervigilance and worry.

Early achievement

Some children excel academically or socially at a young age, receiving praise but also heightened expectations from parents, teachers, or themselves.

Over time, this pressure can foster perfectionism and the belief that success is the only way to feel secure.

Treatment Options for High-Functioning Anxiety

Many people with high-functioning anxiety are reluctant to seek treatment. Some worry that without their anxiety, they won’t be as productive or successful. As one person shared:

“I kept telling myself, ‘my anxiety is what keeps me on top of things.’ But eventually, I realized it was just burning me out.”

While anxiety can feel like a motivator, it often takes a heavy toll on health, relationships, and well-being.

When to Consider Support

It may be time to seek help if anxiety:

- causes persistent distress or exhaustion

- disrupts sleep or physical health

- strains relationships or self-confidence

- leads to unhealthy coping, like overworking or substance use

Another forum user reflected:

“Everyone thought I was doing fine, but I was drinking every night just to calm down enough to sleep. That’s when I knew I needed help.”

Therapy Options

Therapy can help people manage anxiety without relying on constant pressure. Common approaches include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Reduces perfectionism and self-criticism.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Teaches skills for handling stress and people-pleasing.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Encourages letting go of endless striving.

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Helpful if past experiences fuel anxiety.

Medication

Some people also benefit from medication, which should always be discussed with a qualified professional.

Practical Lifestyle & Self-Help Strategies for High-Functioning Anxiety

When anxiety subtly fuels productivity, finding relief can feel counterintuitive—but small, intentional habits can make a big difference:

- Ground yourself through mindfulness and breathwork

Pause during hyper-productivity and practice grounding techniques like deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, or 5-minute mindfulness breaks. These can help reduce physical tension and interrupt rumination. - Prioritize restful sleep and gentle movement

Fight fatigue by establishing a calming bedtime routine—dim lights, quiet time, and regular sleep hours. Add light exercise, such as a walk or yoga, to shift nervous energy and anchor your body. - Set boundaries around comparison and media

High-functioning anxiety often stems from self-pressure. Experts recommend limiting social media—e.g., setting a 10–15 minute cap—and replacing comparison loops with affirmations like “I deserve rest” or “I am enough as I am.” - Build connection and value-based reminders

Combat internal critics by identifying your core values. Visual cues—photos, words, mementos that represent what truly matters—help re-anchor focus and reduce constant striving.

Why these tips suit high-functioning anxiety:

Each suggestion helps interrupt the ‘productive anxiety’ cycle without negating its motivational effects. They introduce rest, clarity, and self-validation in small, manageable steps.

⚠️ Disclaimer: This content is for informational purposes only. If anxiety feels overwhelming, please consider seeking help from a qualified mental health provider.

References

Ayano, G., Betts, K., Maravilla, J. C., & Alati, R. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of disruptive behavioral disorders in the offspring of parents with severe psychiatric disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(1), 77-95.

Christiansen, D. M. (2015). Examining sex and gender differences in anxiety disorders. A fresh look at anxiety disorders, 17-49.

Government of Western Australia. (n.d.). The Vicious Cycle of Anxiety. Centre for Clinical Interventions. Retrieved 2021, November 19, from: https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/CCI/Mental-Health-Professionals/Panic/Panic—Information-Sheets/Panic-Information-Sheet—03—The-Vicious-Cycle-of-Anxiety.pdf

Nikčević, A. V., Marino, C., Kolubinski, D. C., Leach, D., & Spada, M. M. (2021). Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 578-584.

Zhang, F., Baranova, A., Zhou, C., Cao, H., Chen, J., Zhang, X., & Xu, M. (2021). Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Human Genetics, 1-15.