Cognitive distortions are habitual, inaccurate thought patterns that can lead people to interpret situations more negatively than they really are. These distorted thoughts often arise automatically, especially during periods of stress, anxiety, or depression, and may reflect deeper beliefs about the self, others, or the world.

First identified by psychiatrist Aaron Beck in the 1960s as part of his work in developing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive distortions are now recognized as common contributors to emotional distress.

While occasional distorted thinking is normal, repeated patterns can reinforce mental health challenges and interfere with well-being.

These distortions often develop as coping responses to difficult or prolonged life experiences, but over time, they can become rigid and harmful.

People may believe these thoughts without questioning their accuracy, leading to increased anxiety, low mood, and unhelpful behaviors.

Key Takeaways

- Cognitive distortions are automatic, unhelpful thoughts that worsen anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

- There are 13 common types, including catastrophizing, mind reading, and black-and-white thinking.

- These patterns often stem from stress, trauma, or mental health conditions like OCD and ADHD.

- CBT helps people recognize and reframe distorted thoughts using tools like thought records and Socratic questioning.

- Self-help strategies include labeling behavior, replacing extreme language, and spotting positive aspects.

1. Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization involves drawing sweeping negative conclusions based on a single event.

A person might assume one bad experience defines all future outcomes.

Example: After an awkward first day at a new job, someone may think, “I’ll never succeed here.”

Phrases like “always” or “never” often signal this pattern, which is common in depression and anxiety and can reinforce helplessness and low self-worth.

2. Mental Filtering

Mental filtering means focusing exclusively on the negative parts of a situation while ignoring the positive.

Example: After a great date, you fixate on a minor disagreement and remember the evening as a failure.

This tunnel vision can distort perception, feeding depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.

3. Discounting the Positive

This distortion minimizes or dismisses positive experiences as unimportant or undeserved.

Example: You ace a job interview but assume, “They were just being nice.”

It’s common in low self-esteem and depression and prevents people from internalizing success or feeling capable.

4. Jumping to Conclusions

Jumping to conclusions means assuming negative outcomes without evidence. It includes:

- Mind reading: “She didn’t text back—she must be mad at me.”

- Fortune-telling: “I’ll mess up this presentation even though I’ve done well before.”

These patterns heighten anxiety and avoidance, especially in social or performance situations.

5. Magnification and Minimization

This distortion exaggerates flaws and downplays strengths, often flipping reality.

Example: You obsess over a small mistake (“I failed completely”) while dismissing praise (“It wasn’t a big deal”).

It’s like looking through a distorted lens—magnifying the bad, minimizing the good—and contributes to anxiety, shame, and avoidance.

6. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning assumes feelings are facts. If you feel something is true, you believe it must be.

Example: “I feel like a failure, so I must be one.”

This thinking style can fuel anxiety and depression by turning temporary emotions into fixed beliefs.

7. ‘Should’ and ‘Must’ Statements

This distortion imposes rigid expectations on yourself or others, often leading to guilt, frustration, or resentment.

Example: “I should never make mistakes” or “They must know better.”

When these expectations aren’t met, they can create internal pressure or conflict in relationships.

8. Labeling

Labeling means assigning global, negative identities to yourself or others based on specific actions.

Example: You spill coffee and think, “I’m such an idiot,” or someone ignores you once and you decide, “They’re rude.”

It oversimplifies people and situations, damaging self-esteem and relationships.

9. Personalization and Blame

Personalization involves blaming yourself for things beyond your control, while blame shifts all responsibility to others.

Example: “It’s my fault the team failed,” even if others contributed.

This thinking is common after trauma or in depression, and it fosters guilt, shame, or resentment.

10. Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing is when you imagine the worst-case scenario, no matter how unlikely.

Example: You hear a noise at night and immediately think, “Someone’s breaking in.”

This distortion escalates fear and stress, especially in those with anxiety disorders.

11. Black-and-White Thinking (All-or-Nothing)

This thinking sees situations in extremes—success or failure, good or bad—with no in-between.

Example: A student who doesn’t get straight As thinks, “I’m a total failure.”

It leads to perfectionism, low resilience, and a distorted view of reality.

12. Mind Reading

Mind reading involves assuming you know what others are thinking—usually in a negative way—without any real evidence.

Example: A friend checks their phone while you’re talking, and you think, “They must find me boring,” when they might just be waiting for a message.

It’s common in anxiety and can lead to misinterpreting others’ behavior, fueling unnecessary worry and self-doubt.

13. Predictive Thinking

Predictive thinking means expecting the worst about future events, often despite past success.

Example: Before a presentation, you think, “I’ll mess up,” even though you’ve done well before.

This distortion often appears in anxiety disorders and can lead to avoidance and heightened stress, reinforcing the fear cycle.

Why Do I Have Cognitive Distortions?

Cognitive distortions are common, automatic thinking patterns that can develop in response to stress, mental health conditions, or past experiences.

While everyone experiences distorted thoughts at times, certain conditions make them more frequent or intense. Here’s how different factors can contribute:

Anxiety and Depression

These conditions often fuel and are fueled by cognitive distortions.

- In anxiety disorders, distortions like catastrophizing (“What if the worst happens?”) or mind reading (“They must be judging me”) amplify fear and avoidance.

- In depression, patterns like all-or-nothing thinking or discounting the positive reinforce feelings of failure, hopelessness, and low self-worth.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

While not a formal symptom, distorted thinking is deeply involved in OCD.

People with OCD may overestimate danger, fear uncertainty, or believe their thoughts can cause harm (known as thought-action fusion).

These distortions drive obsessions and compulsions aimed at regaining control or certainty.

Trauma and PTSD

Traumatic experiences can lead to lasting cognitive distortions.

For example, a person might develop beliefs like “I’m not safe” or “It was all my fault.”

These thoughts often become automatic and persist long after the trauma, reinforcing fear, guilt, or hypervigilance.

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder)

ADHD doesn’t cause cognitive distortions directly, but it can contribute through repeated challenges with focus, follow-through, and emotional regulation.

Many people with ADHD develop beliefs like “I’m lazy” or “I always mess things up.”

These distortions often stem from years of frustration or negative feedback, and can intensify shame, anxiety, or perfectionism.

Cognitive distortions often reflect how someone has learned to interpret the world—especially in the face of stress, trauma, or unmet needs.

Consequences of Cognitive Distortions

Cognitive distortions can quietly shape how we see ourselves, others, and the world—often with real-life consequences.

In relationships, they can fuel conflict, miscommunication, and emotional reactivity.

For example, mind reading or “should” statements can create tension, especially in codependent or insecure attachment patterns.

Distorted thinking also clouds decision-making. Jumping to conclusions or catastrophizing may lead to impulsive choices, avoidance, or missed opportunities.

Social media can amplify distortions like comparison and labeling, increasing anxiety, self-doubt, and unrealistic expectations.

In anxiety—especially generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)—distortions like threat appraisal, intolerance of uncertainty, and catastrophic thinking drive excessive worry and safety behaviors that reinforce fear.

Similarly, in depression, distortions align with Beck’s cognitive triad: viewing the self, world, and future negatively. They contribute to low mood, rumination, and feelings of hopelessness or anhedonia.

Cognitive distortions also erode self-esteem by shaping a negative self-concept and reinforcing limiting core beliefs.

People may underestimate their capabilities (low self-efficacy), compare themselves harshly to others, and struggle to feel a sense of self-worth.

Over time, these thinking patterns can limit emotional well-being, damage relationships, and hold people back from pursuing goals or connecting with others authentically.

How Are Cognitive Distortions Treated?

Cognitive distortions are most commonly treated using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—a short-term, evidence-based approach that helps people identify, challenge, and reframe unhelpful thought patterns.

At the heart of CBT is the idea that our thoughts shape how we feel and behave.

When distorted thoughts dominate, they can lead to anxiety, depression, and other mental health difficulties.

CBT teaches people to recognize these distortions and replace them with more realistic, balanced thinking.

How does CBT challenge cognitive distortions?

CBT focuses on the present and uses structured techniques to question and reshape unhelpful thoughts.

Clients are taught to become aware of their automatic thoughts, label distortions (like catastrophizing or mind reading), and evaluate whether those thoughts are accurate or helpful.

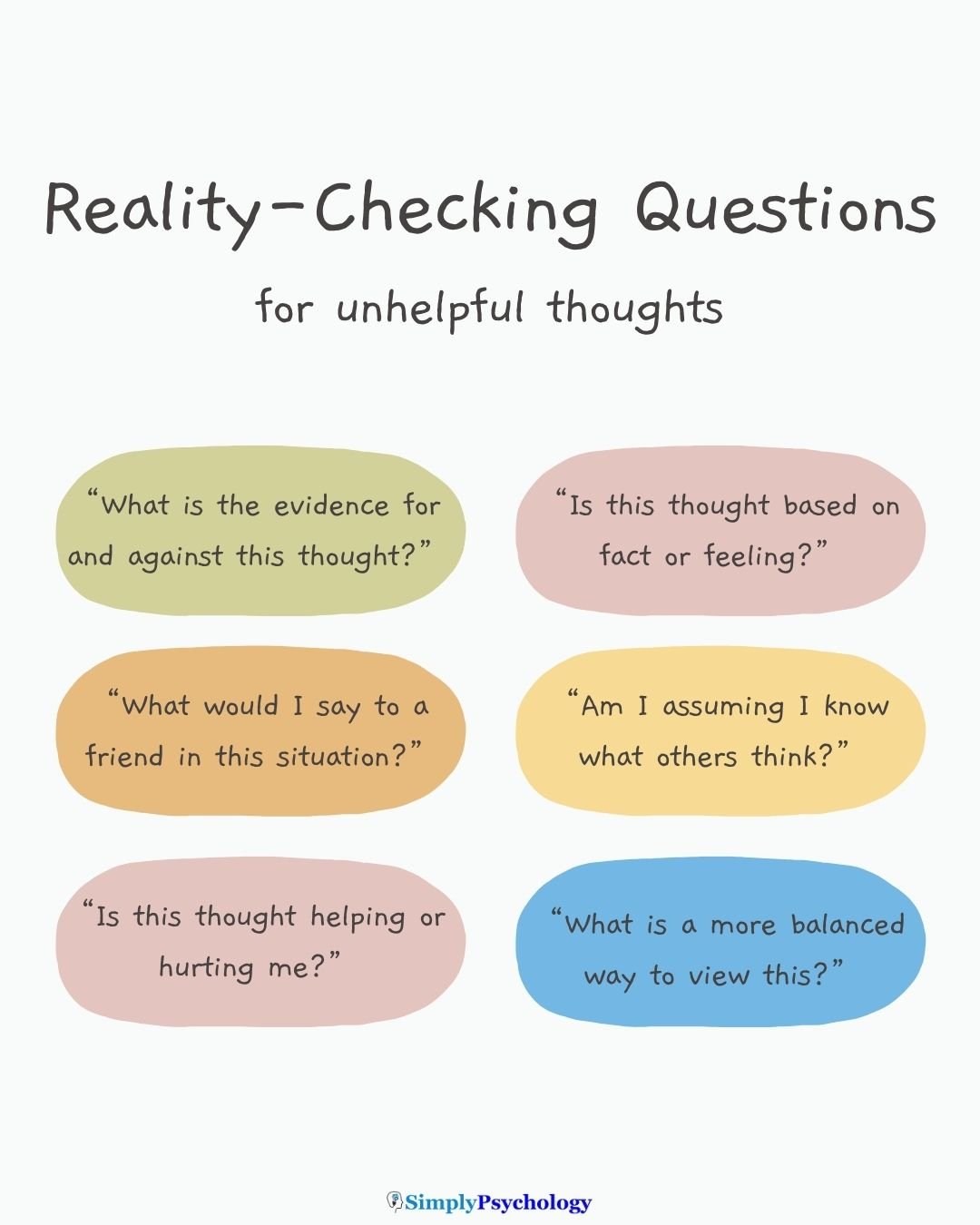

What are Socratic questions in CBT?

Therapists often use Socratic questioning, a guided form of inquiry that encourages the client to think critically about their beliefs.

For example, they may ask, “What’s the evidence for this thought?” or “What might you say to a friend who thought this?”

These questions help the client examine and soften rigid thinking.

How do therapists reframe distorted thoughts?

Reframing involves helping the client develop alternative, more balanced interpretations of events.

A therapist might help someone replace “I always fail” with “I struggled this time, but I’ve succeeded before.”

Over time, this process reduces emotional distress and builds psychological flexibility.

How does CBT work?

CBT is typically structured, goal-oriented, and time-limited (often 5–20 sessions), with homework assignments to practice skills outside therapy.

Research shows it’s highly effective for treating anxiety, depression, OCD, PTSD, and other conditions.

While CBT isn’t suitable for everyone, it remains one of the most widely recommended treatments for cognitive distortions.

How to Manage Cognitive Distortions

Cognitive distortions can feel automatic and convincing—but they can be challenged.

With consistent practice and the right tools, you can learn to recognize these thought patterns and replace them with more balanced, realistic thinking.

Below are evidence-based strategies used in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and self-help approaches.

1. Identify the Distortion

Start by noticing when a thought triggers anxiety, shame, or low mood. Ask yourself:

- What am I thinking right now?

- What emotion is connected to this thought?

- Which cognitive distortion could this be—catastrophizing, black-and-white thinking, mind reading?

Using a thought record or CBT worksheet can help you track recurring patterns and become more aware of your internal dialogue.

2. Reframe the Thought

Once you’ve identified a distortion, try looking at the situation from another perspective.

Ask yourself:

- What’s another way to see this?

- What would I say to a friend with this thought?

- Is there a more balanced or helpful way to think about this?

This process—called cognitive restructuring—is a key part of CBT and helps reduce emotional distress.

3. Use Socratic Questions

Challenge the thought by questioning its validity. Examples include:

- What evidence supports this thought?

- What evidence goes against it?

- Am I confusing a feeling with a fact?

- Am I jumping to conclusions or assuming what others think?

This reflective questioning helps you pause and assess your thoughts more objectively.

4. Do a Cost-Benefit Analysis

Unhelpful thought patterns sometimes serve a purpose, such as creating a sense of control or avoiding discomfort. Ask yourself:

- How has this thought helped me cope in the past?

- How is it limiting me now?

- What do I gain or lose by holding onto this belief?

Evaluating the pros and cons can create motivation to change and increase psychological flexibility.

5. Replace Absolute Language

Distortions often include extreme terms like “always,” “never,” or “everyone.” Replacing these with more moderate language helps shift your thinking toward nuance and accuracy.

For example:

- “I always mess up” becomes “Sometimes I make mistakes, but I also succeed.”

- “No one cares” becomes “Some people may not show it, but others do care.”

This technique reduces emotional intensity and improves self-talk.

6. Label the Behavior, Not the Person

Instead of saying, “I’m a failure,” describe the situation factually: “I missed a deadline.”

This small shift reduces self-blame and encourages a growth mindset, helping you focus on specific actions rather than global judgments.

7. Find the Evidence

Before believing a negative thought, examine the evidence. Ask:

- Is this based on facts or just how I feel?

- What are the facts that support or contradict this thought?

- Am I overlooking any alternative explanations?

Writing down evidence for and against a thought can help you step back and evaluate how realistic it truly is.

8. Search for Positive Aspects

When you catch yourself focusing on what went wrong, challenge yourself to identify things that went right.

This strengthens cognitive balance and reduces mental filtering. You might try:

- Naming three things that went well today

- Recognizing a small personal win

- Noting one strength you showed in a tough moment

Over time, this practice can help rewire your brain to notice both the positive and the negative more evenly.

9. Practice Mindfulness and Self-Compassion

Mindfulness helps you observe your thoughts without reacting or judging them, while self-compassion reminds you that being imperfect is part of being human.

Together, these practices make it easier to acknowledge distorted thinking without believing everything your mind tells you.

Do you or a loved one need mental health help?

USA

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

References

Binnie, J., & Blainey, S. (2013). The use of cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders: a review of the evidence. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(2), 93-104.

Carpenter, J. K., Andrews, L. A., Witcraft, S. M., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Depression and anxiety, 35(6), 502-514.

DeRubeis, R. J., Siegle, G. J., & Hollon, S. D. (2008). Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(10), 788-796.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive therapy and research, 36, 427-440.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive therapy and research, 36(5), 427-440.

Lam, D. H., Bright, J., Jones, S., Hayward, P., Schuck, N., Chisholm, D., & Sham, P. (2000). Cognitive therapy for bipolar illness—a pilot study of relapse prevention. Cognitive therapy and research, 24, 503-520

Lopes, R. T., Gonçalves, M. M., Machado, P. P., Sinai, D., Bento, T., & Salgado, J. (2014). Narrative Therapy vs. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for moderate depression: Empirical evidence from a controlled clinical trial. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 662-674.

Mendes, D. D., Mello, M. F., Ventura, P., de Medeiros Passarela, C., & de Jesus Mari, J. (2008). A systematic review on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 38(3), 241-259.

Nathan, P., Rees, C., Lim, L., & Correia, H. (2003). Back from the Bluez. Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Clinical Interventions.

Salla, M., Aguilera, M., Paz, C., Moya, J., & Feixas, G. (2025). The effect of cumulative trauma and polarised thinking on severity of depressive disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice.

Scott, J., Garland, A., & Moorhead, S. (2001). A pilot study of cognitive therapy in bipolar disorders. Psychological medicine, 31(3), 459-467.

Sizoo, B. B., & Kuiper, E. (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness based stress reduction may be equally effective in reducing anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in developmental disabilities, 64, 47-55.

Velthorst, E., Koeter, M., Van Der Gaag, M., Nieman, D. H., Fett, A. K., Smit, F., Staring, ABP, Meijer, C. & De Haan, L. (2015). Adapted cognitive–behavioural therapy required for targeting negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological medicine, 45(3), 453-465.

Further Information

Information Sheets on the Unhelpful Thinking Styles – Centre For Clinical Interventions (CCI)