Mental filtering (also called selective abstraction) is a common cognitive distortion where a person fixates on the negative parts of an experience while ignoring the positives.

You might zero in on one bad moment and let it overshadow everything else in the same way that a single drop of ink can darken an entire glass of water.

For instance, you may receive praise from several coworkers, but one mild critique sticks with you all night. The positives fade, and that one comment feels like the whole truth.

Download our free reflection sheet on this topic:

Mental Filtering Reflection Sheet

Mental filtering can lead you to ruminate on mistakes or awkward moments, even in otherwise good situations.

Maybe a colleague applauds most of your work, but you dwell on one correction. Or perhaps your day went well until a brief awkward exchange convinced you, “Today was terrible.”

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. We all have a tendency to focus more on what’s wrong, and mental filtering is one way that bias shows up.

Why Mental Filtering Happens

Mental filtering stems from how we process information, especially under stress or with negative thinking patterns.

Psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, founder of cognitive therapy, noted that people often have automatic negative thoughts shaped by underlying beliefs or schemas.

These schemas distort perception, causing even neutral or positive events to seem negative. If someone believes “I’m not good enough,” they may filter out praise and fixate on the slightest criticism.

This pattern becomes self-reinforcing. Negative thoughts fuel painful emotions, which in turn strengthen the distortion.

Adding to this is the brain’s negativity bias — our built-in tendency to notice threats more than rewards. People may describe criticism as feeling so powerful that it becomes “obsessive”.

From an evolutionary perspective, remembering dangers helped our ancestors survive, but in modern life, it can lead us to fixate on daily negatives that aren’t life-threatening.

Stress and past experiences also play a role. People who grew up with frequent criticism or trauma may unconsciously scan for negativity as a learned defense.

Mental filtering is common in anxiety and depression. Small disappointments may feel like confirmation of worst-case fears, while positive feedback gets dismissed.

Even minor triggers can spark waves of distorted thinking in people with these conditions, reinforcing a cycle: the more you filter out positives, the more hopeless or anxious you feel, and the stronger the filter becomes.

Examples of Mental Filtering

This distortion shows up in everyday moments. Here are a few examples:

- Workplace criticism: You present successfully, but one colleague mentions a flaw. Despite all the praise, you replay the critique and feel like the whole thing was a failure.

- Dismissing compliments: Friends or family say something kind, but you brush it off, thinking they’re just being polite. One person noted they tend to reject praise, assuming people have hidden motives.

- Fixating on one bad moment: You have a pleasant day overall, but a short argument with your partner in the evening ruins it. When you reflect, all you can think about is that fight.

In each case, the person is looking through a mental lens that magnifies the bad and minimizes the good. Over time, this reinforces a habit of spotting the next negative detail.

How Mental Filtering Affects You

Constantly filtering for the negative can drain your emotional and mental well-being.

Emotionally, it often leads to anxiety, sadness, or low self-worth. Replaying distressing thoughts keeps you stuck in a cycle of worry or regret.

One person shared that ruminating on small mistakes makes their emotions “run amok” and spirals them into thinking their life is worthless.

Mentally, this distortion skews your view of reality. You may believe the filtered version of events — “I failed” or “Nothing went well” — even if it’s inaccurate.

We often believe our filtered perspective without realizing it’s a distortion.

This pattern can also erode your self-esteem. Ignoring evidence of your strengths while focusing on flaws reinforces a belief that you’re inadequate.

This affects confidence, motivation, relationships, and decision-making. You might avoid challenges, withdraw socially, or stop taking initiative at work for fear of making mistakes.

Some people eventually feel too demoralized to pursue goals or care for themselves, trapped in a smaller, more fearful version of life.

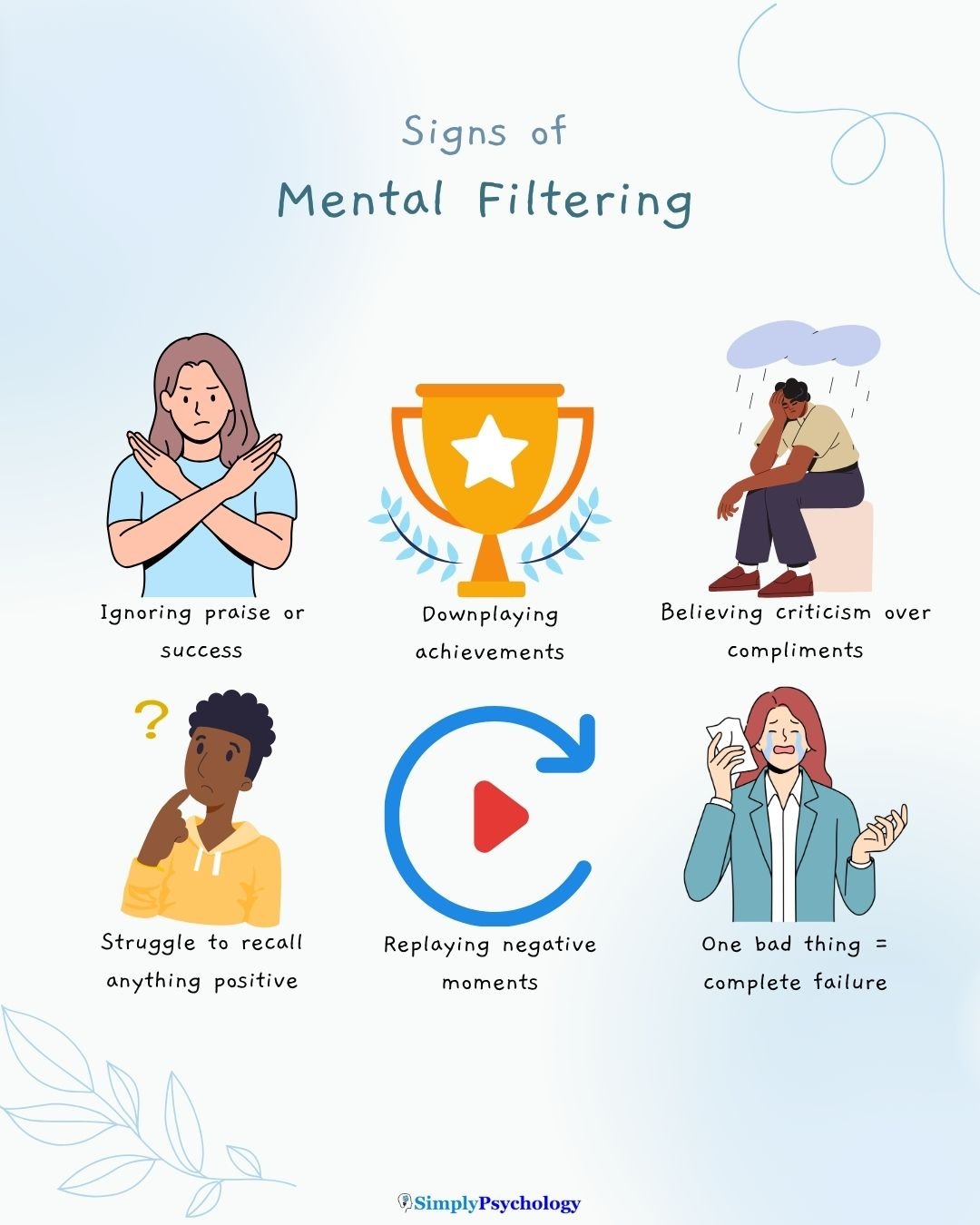

Signs You Might Be Mentally Filtering

How do you know if this pattern applies to you? Here are a few signs:

- Replaying negative moments: You obsess over a mistake or embarrassing moment, sometimes days later. Even minor missteps may stay with you for days or longer.

- Dismissing compliments: You downplay positive feedback or achievements, thinking they don’t really count or that people are just being kind.

- Forgetting the good: When asked what went well in your day, you draw a blank. Negative events tend to stick, while positives fade. When you’re stuck in this distortion, good moments might as well not exist.

Recognizing these signs is the first step. While everyone has negative thoughts now and then, consistent patterns of filtering may signal the need for change.

How to Challenge Mental Filtering

Challenging this distortion involves catching the thought, questioning it, and replacing it with a more balanced view. These cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) steps help shift your thinking:

Notice the filter

Pay attention to your inner dialogue. If you hear yourself thinking, “I messed up again — nothing ever goes right,” pause and name it: “That’s a mental filter.”

Catching the thought in real time can feel like the hardest part for many because it feels so automatic, but with practice, it can become easier.

Look for missing information

Ask, “Is this the whole picture?” Often, you’ll realize you’re focused on one detail so challenge the thought by recalling overlooked positives.

For example, if you think, “I botched that meeting,” remember a point someone agreed with or your good preparation.

Writing down pros and cons can help rebalance the view. Therapists call this technique “checking the evidence”.

Reframe the thought

Once you find counter-evidence, revise the thought. Instead of “I failed,” try “It wasn’t perfect, but I did well overall.”

Or if you’re assuming someone’s mad at you, consider “They seemed quiet — maybe they were tired.”

Ask, “What would I tell a friend in this situation?” This trains your brain to see the fuller picture.

Keep a thought journal

Writing down upsetting thoughts and then adding alternative interpretations helps break patterns.

Journaling makes it easier to see thinking habits and brainstorm more balanced perspectives.

Some people even do a cost-benefit analysis of their filtering habit to see how much it really helps vs. harms them.

Even if you catch the thought after the fact, that’s still progress. These techniques are core to CBT and work over time to untangle distorted thinking.

Other Strategies That Can Help

Beyond thought-challenging, several habits can reduce mental filtering:

- Practice mindfulness: Mindfulness helps you observe thoughts without believing them. It increases “metacognition” — awareness of your thinking — so you can recognize when a negative filter takes over. Even a few minutes of breathing or body-scan meditation daily can help interrupt negative spirals.

- Use gratitude journaling: This practice retrains your brain to notice positives. Writing down three things you’re grateful for each day can offset the negativity bias. Even small things like “the smell of coffee” count. Over time, this shifts your mental filter to catch more positive details.

- Take perspective: Ask how you’ll view the issue next week or next year. Or imagine what advice you’d give a friend. One person said they calm down by remembering “how big the universe is and how small my problems are”. Perspective helps shrink problems back to size.

- Do something enriching: Behavioral activation means doing enjoyable or meaningful activities, even when you don’t feel like it. This creates positive experiences and interrupts brooding. Whether it’s a walk, a call with a friend, or a hobby, these moments give your brain something good to latch onto — making the negative filter less convincing.

Together, these strategies form a toolkit for retraining your mind. They help shift your perception toward balance, not forced positivity.

When to Seek Professional Support

If mental filtering seriously affects your mood, relationships, or daily functioning, professional help may be needed. Therapy can be especially helpful if:

- You feel depressed, anxious, or hopeless: Filtering may fuel deep feelings of despair or self-doubt. Therapists can help reframe these patterns.

- It impacts your relationships or work: You might reject compliments or over-focus on mistakes, which can strain your relationships or limit your performance.

- Self-help isn’t enough: If you’ve tried strategies but still feel stuck, therapy can offer personalized guidance. CBT is proven to help with cognitive distortions and mood disorders.

Seeking support is a sign of strength, not weakness. Even short-term therapy can provide tools that last a lifetime.