Hypervigilance refers to a state of constant, heightened alertness—always watching, always waiting for danger—even when the environment is safe.

In the context of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), it is one of the core symptoms that keeps the “alarm system” running, long after the traumatic threat has passed.

While hypervigilance may once have felt protective, over time, it becomes exhausting, intrusive, and disruptive to daily life. Sleep becomes restless, concentration frays, relationships feel strained, and just relaxing feels impossible.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or mental health condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this site.

What Is Hypervigilance?

Vigilance is a normal, adaptive response: being alert to truly dangerous cues (e.g., hearing a crack in the floorboard at night) so we can respond appropriately.

Hypervigilance, by contrast, is a maladaptive extension of that response — the nervous system stays “on high alert” even when danger is unlikely or absent.

In this state, the brain’s threat-detection circuits are over-tuned, interpreting ambiguous or benign stimuli (a door creaking, footsteps) as possible threats.

Over time, that constant readiness becomes itself a stressor: it drains energy, fuels anxiety, and makes it hard to rest.

In PTSD, an anxiety disorder, hypervigilance is one of the core symptoms. The traumatic memory “teaches” the brain to expect danger, so the alarm system remains triggered long after the trauma.

Even safe settings are scanned for cues of threat, and the body remains primed to respond.

Imagine sitting in your living room when a door slams elsewhere in the house. A person without hypervigilance might pause, see nothing seems wrong, and return to relaxed state.

But someone with hypervigilance may jump, heart racing, scan windows and exits, tense every muscle — even though no real danger is present. That’s the nervous system stuck in “overdrive.”

Hypervigilance vs. Paranoia

Hypervigilance is a future-oriented scanning state — looking out for threats that might happen — and usually occurs with insight (you may know your reaction is exaggerated).

Paranoia, by contrast, involves fixed irrational beliefs that others are actively out to harm you now, often without insight or reality testing.

In other words: hypervigilance, according to PTSD UK is about being ‘on guard’ and always on the lookout for hidden dangers, both real and presumed; paranoia is about believing there is a real threat aimed at you, even when evidence is absent.

Why Hypervigilance Happens in PTSD

When someone experiences trauma, the body’s protective alarm system (the fight-or-flight response) is engaged in full force.

Normally, once a threat passes, that system quiets and returns to baseline. But in PTSD, something changes — the “off switch” doesn’t fully reset. Instead, the brain and body remain sensitized, ready to detect danger at all times.

At the neural level, two regions often implicated are the amygdala and the insula.

The amygdala acts as a danger-detector and rapidly signals threat-related stimuli; in PTSD, it can become over-reactive, interpreting ambiguous input (a creaking floorboard, sudden shadow) as potentially dangerous.

Neuroimaging studies also find stronger functional connectivity between the amygdala and insula in PTSD, meaning heightened integration between threat detection and internal bodily awareness (like sensing one’s heartbeat or arousal) — a coupling that may support persistent alertness even in safe contexts.

Because of these changes, the brain’s baseline shifts: signals that used to be ignored become amplified.

The prefrontal cortex (which helps regulate threat responses) and hippocampus (which situates memories in time and context) may have diminished capacity to “talk down” the alarm system.

Over time, this causes the nervous system to live in a state of chronic readiness.

It’s important to emphasize: hypervigilance is not a personal failing or sign of weakness. Rather, it’s a deeply understandable response to trauma that became stuck.

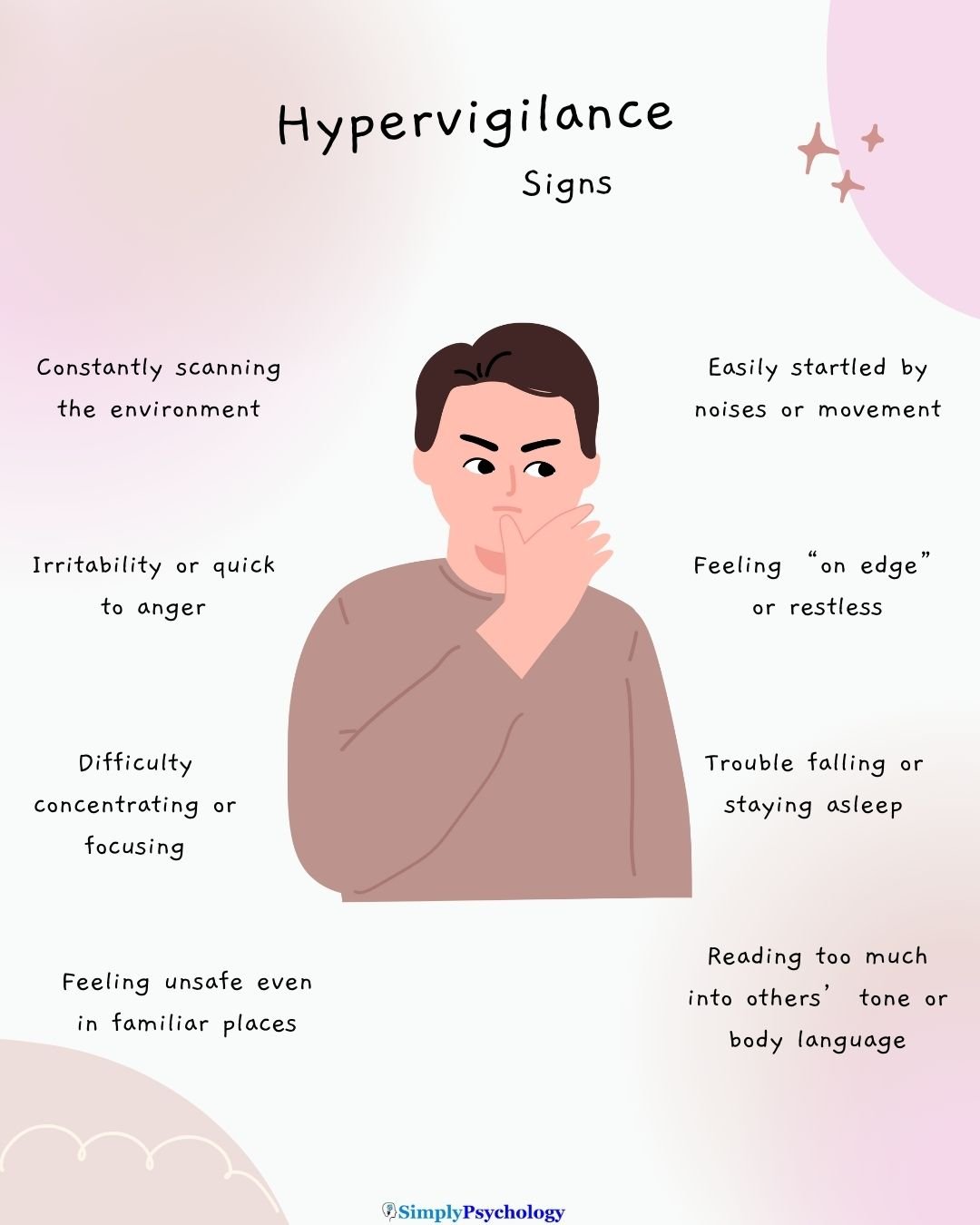

Signs and Symptoms of Hypervigilance

When hypervigilance sets in, it may show up across multiple domains—body, mind, and behavior. The experience varies from person to person, but below are common patterns you might recognize in yourself or someone you care about.

Physical Signs

- Rapid heartbeat, sweating, trembling — the body stays in a state of “readiness,” even when there’s no real threat.

- Sleep disruption — falling asleep or staying asleep becomes difficult, with frequent awakenings, light sleep, or nightmares.

- Increased startle response — even minor noises or movements trigger a jolt or jump, as though danger is lurking.

- Muscle tension, headaches, fatigue — ongoing tension in muscles or chronic physical discomfort from being on edge.

Emotional Signs

- Persistent anxiety or worry — a low-level dread or sense that something bad might happen.

- Irritability or mood swings — small frustrations feel magnified, leading to disproportionate emotional reactions.

- Emotional exhaustion or overwhelm — the constant alertness is draining, leaving you feeling worn out, numb, or emotionally fragile.

- Hyperawareness of others’ intentions — reading into tone, body language, or subtle cues, often with suspicions.

Behavioral Signs

- Avoidance — shying away from settings or people that feel unsafe (e.g., crowded places, social events, certain topics).

- Vigilant scanning or surveillance — monitoring exits, keeping visual on surroundings, arriving early to “scope things out.”

- Heightened defensiveness or aggression — quick to react, justify, or defend oneself even when the perceived threat is minimal.

- Restricted behavior — limiting spontaneity or novelty to reduce unexpectedness (e.g., always sticking to a safe route home).

Note: Not everyone will experience every sign, and severity can fluctuate over time. These symptoms overlap with anxiety, stress, and other conditions. Only a qualified mental health professional can make a formal diagnosis. If these signs feel familiar and interfere with daily life, it may be helpful to seek professional guidance.

Daily Life Impact

Hypervigilance can quietly shape many areas of life, making everyday routines more exhausting and isolating.

Work and Concentration

At work, staying focused often feels like an uphill battle. Every sudden noise, movement, or light change can pull attention away, leading to mistakes or burnout.

Meetings, deadlines, or crowded offices may feel overwhelming, prompting avoidance or withdrawal.

Relationships and Trust

Hypervigilance can strain relationships by fostering mistrust or misinterpretations of others’ tone and intentions.

A partner’s neutral comment may feel loaded with criticism, or a friend’s delay in responding might spark suspicion.

Defensive reactions to perceived slights can escalate conflict, leaving both sides feeling misunderstood. Over time, this can lead to emotional distance and isolation.

Health and Emotional Well-Being

The physical and emotional toll is significant. Chronic fatigue, headaches, muscle tension, and irritability often follow the body’s constant state of readiness.

Restless sleep compounds the problem, leaving little opportunity to recharge.

The Cycle of Exhaustion

This creates a vicious cycle: poor sleep and fatigue increase alertness, which fuels more reactivity, which in turn worsens exhaustion. For many, this cycle makes it hard to ever feel truly safe or relaxed.

Common Triggers

A trigger is any stimulus—internal or external—that reignites the sense of threat or danger learned during trauma.

Triggers matter because they can cause a sudden surge in stress, hypervigilance, or re-experiencing symptoms, even in otherwise safe environments.

Understanding them helps reduce shame, recognize patterns, and plan ahead.

Sensory Triggers

Sounds, smells, textures, or visual cues that resemble aspects of the traumatic event can feel threatening.

For instance, sudden loud noises, a strong scent, or flickering lights may spark the body’s alarm system—long before conscious awareness.

Situational Triggers

These triggers relate to places or settings. Crowded areas, narrow hallways, or environments similar to the original trauma can feel unsafe.

Visiting a location tied to the past event may prompt intense reactions, even if nothing harmful is happening now.

Emotional / Social Triggers

Conflict, criticism, rejection, betrayal, or emotional vulnerability can provoke strong responses. Even subtle remarks or nonverbal cues (tone of voice, facial expressions) may be read as threatening in a hypervigilant state.

Media Reminders

Movies, news stories, documentaries, or images that echo or reference the trauma can reactivate hypervigilance.

A scene in a film, the sound of gunfire, or even a news segment with intense themes may feel very close to real danger.

Coping and Treatment Options

When hypervigilance interferes with quality of life, combining professional intervention with self-soothing practices tends to offer the best path forward.

Therapy

- Trauma-focused CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) can help people reframe unhelpful beliefs, reduce avoidance, and gradually face distressing memories in a safe context.

- Exposure therapies / Prolonged Exposure: in safe doses, people are guided to approach reminders of trauma (imagined or real) so the brain can learn they’re no longer dangerous.

- EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing): while recalling distressing memories, bilateral stimulation (e.g., eye movements) can help reduce their emotional intensity.

These therapies are often first-line for PTSD.

Medication

Medications may support treatment, especially when symptoms are severe or interfering with therapy:

- SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) are common first-line medications in PTSD care.

- Beta-blockers or benzodiazepines are sometimes used short-term for acute anxiety or hyperarousal, but typically with caution due to side effects and dependence risk.

Any medication use should be overseen by a psychiatrist or medical practitioner; these are adjuncts, not replacements for therapeutic work.

Self-Help and Coping Skills

Even alone or between sessions, these techniques can help regulate the nervous system:

- Mindfulness & grounding

Gently direct your attention to present-moment sensory experience (e.g. noticing five things you can see, feel, hear). These practices have empirical support in reducing hyperarousal and emotional reactivity in PTSD populations. - Breathing techniques

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing — e.g., inhaling for 4 counts, exhaling for 6 — can stimulate the parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) branch of the autonomic nervous system, helping to calm physiological arousal. - Exercise & self-care

Regular movement (walking, yoga, gentle aerobic activity) not only releases endorphins but helps “burn off” chronic tension. Adequate sleep hygiene, nutrition, and enjoyable/leisure activities further reinforce resilience.

Note: None of these strategies replaces individualized clinical care. The most effective plan is one tailored to your history, symptoms, and preferences—ideally guided by a trained therapist or psychiatrist. If symptoms feel overwhelming or persist, seeking professional support is a valid and brave step.

Do you need mental health help?

USA

If you or a loved one are struggling with symptoms of PTSD, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

1-800-662-4357

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

References

Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2017). Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience : JPN, 43(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.170021

Campo-Soria, C., Chang, Y., & Weiss, D. S. (2006). Mechanism of action of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors. British journal of pharmacology, 148(7), 984–990. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0706796

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (5th ed.). (2013). American Psychiatric Association.

Evison, I., Watson, G., Chan, C., & Bridgman, P. (2021). The effects of beta-blockers in patients with stress cardiomyopathy. Internal medicine journal, 51(3), 411–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15233

Hur, J., Stockbridge, M. D., Fox, A. S., & Shackman, A. J. (2019). Dispositional negativity, cognition, and anxiety disorders: An integrative translational neuroscience framework. Progress in brain research, 247, 375–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.03.012

Kimble, M., Boxwala, M., Bean, W., Maletsky, K., Halper, J., Spollen, K., & Fleming, K. (2014). The impact of hypervigilance: evidence for a forward feedback loop. Journal of anxiety disorders, 28(2), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.006

Ma, C., Smith, T. E., & Culhane, D. P. (2025). The stress-buffering effects of received social support on posttraumatic stress disorder among Hurricane Ike survivors. Traumatology, 31(2), 276–284.

Marshall, E. M., Karantzas, G. C., Chesterman, S., & Kambouropoulos, N. (2024). Unpacking the association between attachment insecurity and PTSD symptoms: The mediating role of coping strategies. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(1), 86–91.

McCauley, J. L., Killeen, T., Gros, D. F., Brady, K. T., & Back, S. E. (2012). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders: Advances in Assessment and Treatment. Clinical psychology: a publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 19(3), 10.1111/cpsp.12006. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12006

Rabinak, C. A., Angstadt, M., Welsh, R. C., Kennedy, A., Lyubkin, M., Martis, B., & Phan, K. L. (2011). Altered Amygdala Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2, 16583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00062

Sprouse-Blum, A. S., Smith, G., Sugai, D., & Parsa, F. D. (2010). Understanding endorphins and their importance in pain management. Hawaii medical journal, 69(3), 70–71.

Strawn, J. R., Geracioti, L., Rajdev, N., Clemenza, K., & Levine, A. (2018). Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidence-based treatment review. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 19(10), 1057–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2018.1491966

Tseng, & Poppenk, J. (2020). Brain meta-state transitions demarcate thoughts across task contexts exposing the mental noise of trait neuroticism. Nature Communications, 11(1), 3480–3480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17255-9

Van der Kolk B. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/bvdkolk

Weiten, W., McCann, D., & Matheson, D. H. (2022). Psychology: Themes and variations. Cengage. 85-89

Yehuda, R., Hoge, C. W., McFarlane, A. C., Vermetten, E., Lanius, R. A., Nievergelt, C. M., Hobfoll, S. E., Koenen, K. C., Neylan, T. C., & Hyman, S. E. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 1, 15057. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.57

You, M., Laborde, S., Zammit, N., Iskra, M., Borges, U., & Dosseville, F. (2021). Single Slow-Paced Breathing Session at Six Cycles per Minute: Investigation of Dose-Response Relationship on Cardiac Vagal Activity. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(23), 12478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312478

Yuan, H., & Silberstein, S. D. (2016). Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part I. Headache, 56(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12647

Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E., Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353