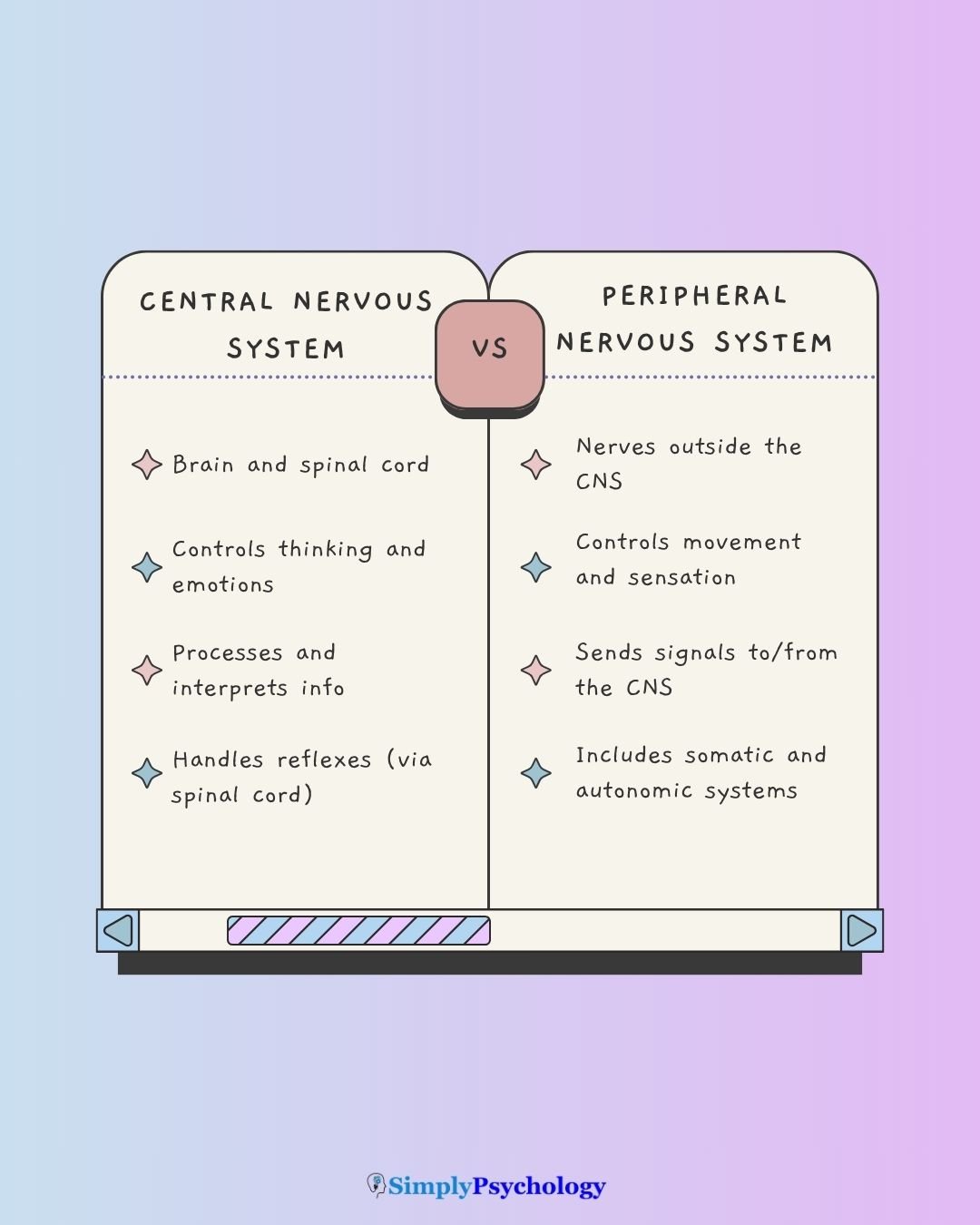

The central nervous system (CNS) is the body’s command center. It includes the brain and spinal cord, which work together to control movement, sensation, thought, and emotion.

By processing information from the senses, the CNS coordinates everything from voluntary actions like walking to automatic functions like breathing and heartbeat.

Without the CNS, we wouldn’t be able to think, feel, or respond to the world. It connects our mental and physical experiences – making it essential not just for survival, but for how we experience life.

CNS Diagram

CNS Functions

The Central Nervous System (CNS), composed of the brain and spinal cord, functions as the body’s primary control centre.

It is responsible for receiving and interpreting sensory information, making decisions, and directing the body’s muscular and physiological responses.

The CNS operates through a continuous cycle of receiving input, processing that data, and initiating output.

1. Core Physiological Functions

The CNS is responsible for both high-level cognitive processes and the maintenance of internal stability (homeostasis).

- Reflex Coordination: The spinal cord facilitates rapid, involuntary responses to stimuli—such as the withdrawal reflex—bypassing the brain for immediate action.

- Sensory Processing: The system receives and interprets data gathered by the peripheral nervous system regarding the environment and the body’s internal state.

- Integration (The Processing Phase): The brain integrates current sensations with existing emotions and memories to form a complete picture of the environment.

- Cognition: Information reaching the brain is processed by the cerebral cortex to create consciousness, reasoning, and language. Uses integrated data to solve problems or use language.

- Motor Command: The brain initiates signals that travel through the spinal cord to trigger voluntary movements (e.g., speech) and regulate involuntary muscle actions.

- Homeostatic Regulation: The hypothalamus maintains internal equilibrium (body temperature, hunger, thirst) by working with the autonomic nervous system.

2. Component Roles

The CNS is divided into two primary anatomical components with specialized roles:

The Brain

- Acts as the primary site for higher-order functions including intelligence, personality, and emotion.

- Manages the interpretation of complex sensory data and the production of speech.

The Spinal Cord

- Functions as the vital communication relay, carrying messages bidirectionally between the brain and the rest of the body.

- Serves as the independent center for coordinating spinal reflexes.

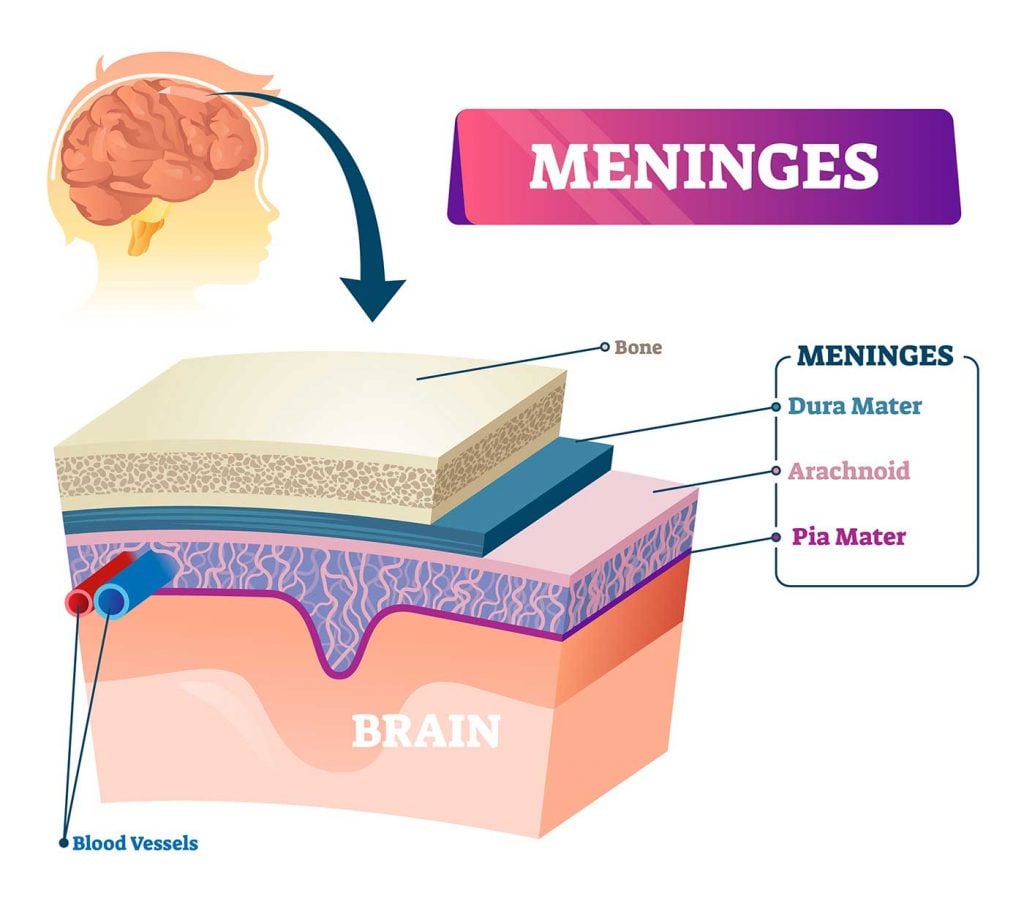

3. Protection and Metabolic Support

Because the CNS is composed of delicate neural tissue, it requires extensive physical and physiological protection:

- Physical Armor: The brain is encased within the skull, and the spinal cord is protected by the vertebral column (vertebrae).

- Meninges: Three protective membranes (dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater) surround the CNS to provide a barrier against injury.

- Nutrient Dependency: The CNS has a high metabolic rate and is heavily reliant on a constant supply of nutrients and oxygen to function.

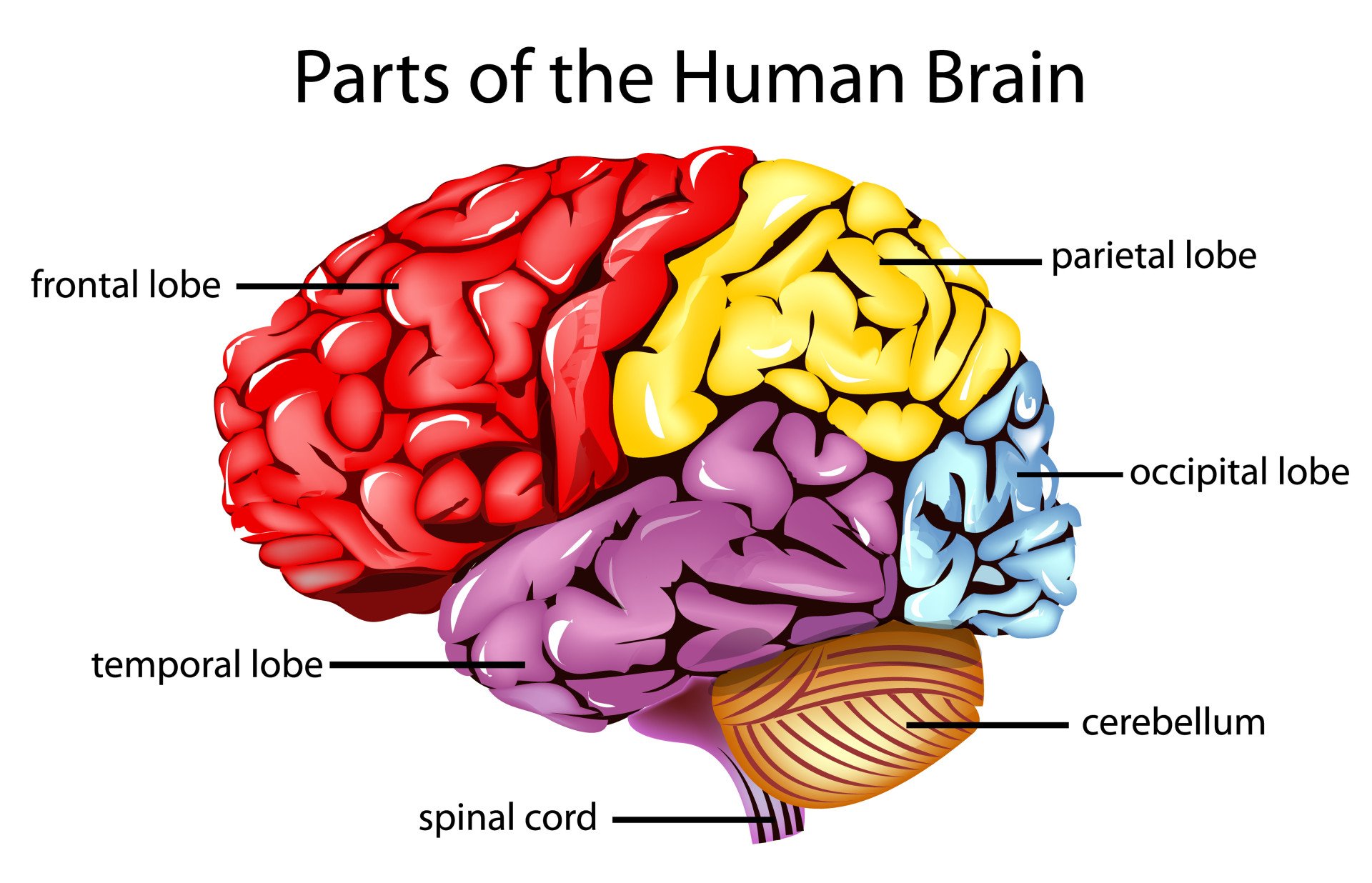

The Brain

The brain is the CNS’s most complex structure. It’s responsible for thinking, memory, movement, and perception.

The brain is the primary control center of the CNS, responsible for processing sensory information, regulating bodily functions, and enabling higher-order cognitive abilities such as thinking and memory.

While the brain is anatomically continuous with the spinal cord, it is distinguished by its high level of structural complexity and specialization.

To understand its function, biologists categorize the brain into three main developmental divisions: the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain.

- Forebrain (Prosencephalon): This is the largest part of the brain and includes the cerebrum, which is responsible for higher-order cognitive abilities like reasoning and memory. It also contains the diencephalon, which houses the thalamus and hypothalamus.

- Midbrain (Mesencephalon): This region serves as a connector between the higher forebrain and the lower hindbrain, managing visual and auditory reflexes.

- Hindbrain (Rhombencephalon): This evolutionary older region controls vital life-support functions through the medulla oblongata (breathing/heart rate) and coordinates motor control via the cerebellum.

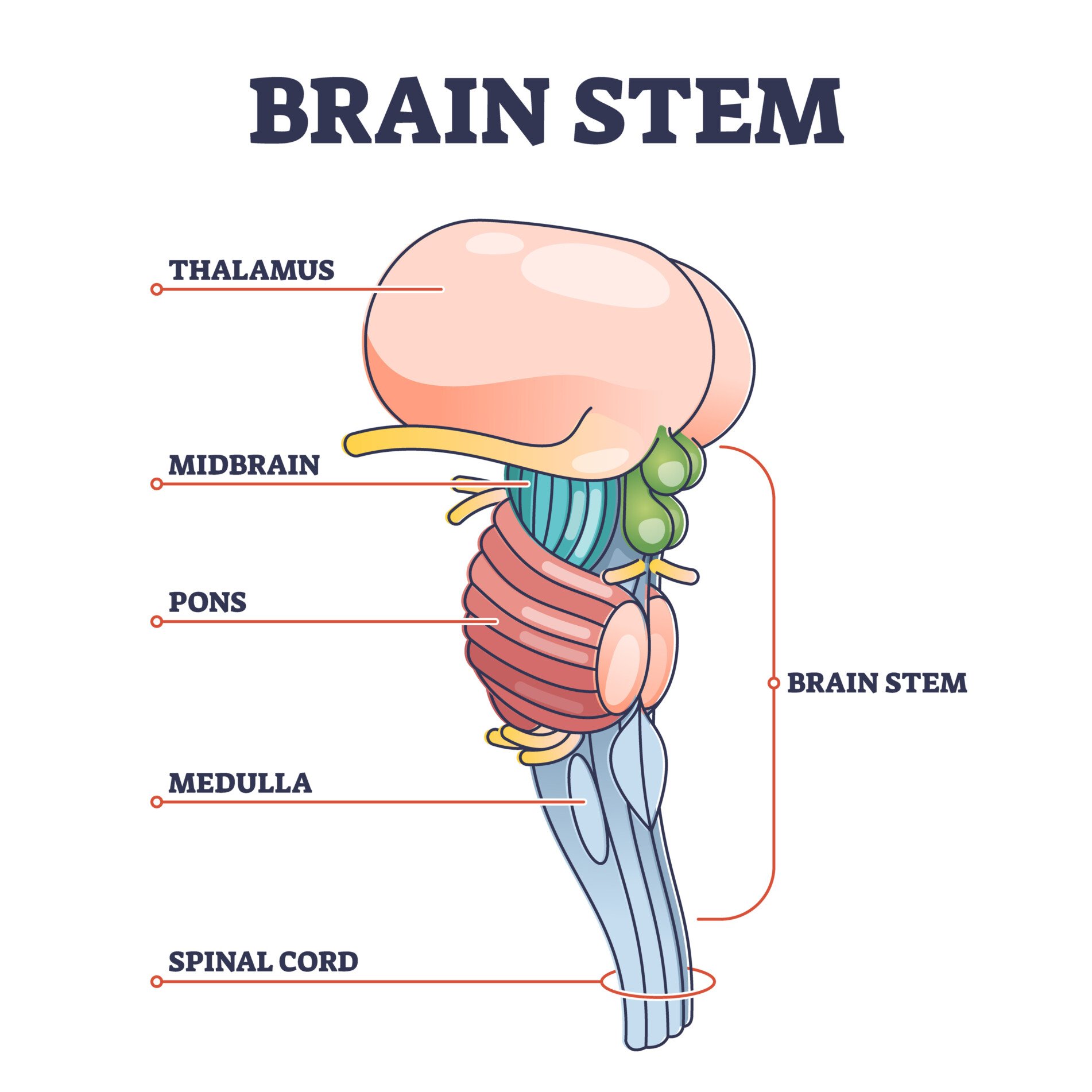

The Brain Stem

The brain stem is located at the base of the brain and is one of the most primitive regions of the brain; and is made up of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata.

The brain stem functions are correspondingly basic and physiological, including automatic behaviors such as breathing and swallowing.

The Cerebellum

Sitting just above the brainstem, the cerebellum regulates motor activity, balance, and posture.

It helps fine-tune movements, especially those we perform automatically, like walking or catching a ball.

In some animals, like amphibians, the brain consists mainly of the brainstem and cerebellum.

The Cerebrum

The cerebrum is the brain’s largest and most recently evolved area, making up about 85% of its mass.

Divided into two hemispheres, it supports higher-level functions including speech, voluntary movement, and problem-solving.

Each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body.

Within the cerebral hemispheres, there are four areas, or lobes, that each serve different functions:

- Frontal lobes – these are positioned at the forefront of the brain and are responsible for higher cognitive functioning, language development, attention, decision-making, and problem-solving.

- Occipital lobes – positioned at the back of the brain, these lobes are responsible for processing and encoding different visual information such as color, orientation, and motion.

- Parietal lobes – situated at the top of the brain, are responsible for processing sensory information, attentional awareness, visuospatial processing, and integrating somatosensory information (e.g., touch, temperature, and pain).

- Temporal lobes – located just behind the ears, the temporal lobes are responsible for the recognition, perception (hearing, vision, smell), understanding of language, and forming memories.

The Cerebral Cortex: Thinking Surface

The surface of the cerebrum is called the cerebral cortex, also known as grey matter.

It’s a 3mm-thick layer packed with billions of neurons.

This is where memories are stored, sensory data is interpreted, and thinking occurs.

The folds and grooves (called gyri and sulci) increase the cortex’s surface area, allowing for more complex neural networks.

White Matter and Connectivity

Beneath the cortex lies white matter – bundles of nerve fibers that connect different brain regions and speed up communication using myelin insulation.

Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin collection of neurons attached to the base of the brain (brain stem), running the length of the spinal column.

The spinal cord contains circuits of neurons that can control some of our simple reflexes, such as moving a hand away from a hot surface without participation from the brain.

It serves two primary functions:

- Transmission: It routes messages to and from the brain, connecting the CNS to the peripheral nervous system.

- Reflexes: The spinal cord can initiate automatic, involuntary responses (such as the knee-jerk reaction) without input from the brain, allowing for faster reactions in survival situations.

Segments of the Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is divided into 30 segments, each serving a specific body area:

- Cervical – These are 8 segments that transmit signals from or to areas of the head, neck, shoulders, arms, and hands.

- Thoracic – These are 12 segments that transmit signals from or to areas of the arms, chest, and abdominal areas.

- Lumbar – These are 5 segments that transmit signals from or to areas of the legs, feet, and some pelvic organs.

- Sacral – These are 5 segments that transmit signals from or to areas of the lower back, pelvic organs, genital areas, and some areas of the legs and feet.

- Coccyx – which is the base of the spinal cord.

How the CNS Communicates with the Body

Neurons

The fundamental unit of the CNS is the neuron, or nerve cell.

The CNS contains about 86 billion neurons, each designed to transmit electrical signals.

Neurons are designed to send and receive information through a specific structure:

- Dendrites: Branch-like fibres that receive messages from other neurons.

- Soma (Cell Body): Contains the nucleus and genetic information; it processes the incoming signals.

- Axon: A tube-like extension that carries electrical impulses (action potentials) away from the cell body toward other neurons.

- Myelin Sheath: A white, fatty covering on axons that provides insulation and increases the speed of signal transmission.

Communication between neurons occurs at the synapse, a gap between the axon terminal of one neuron and the dendrite of another.

When an electrical impulse reaches the end of an axon, it triggers the release of chemical messengers called neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine).

These chemicals cross the synaptic cleft and bind to receptors on the receiving neuron, delivering excitatory (fire) or inhibitory (don’t fire) messages

Glial Cells

Although glial cells don’t send signals themselves, they are vital for maintaining brain health.

They outnumber neurons about 9 to 1. Key types include:

- Astrocytes: Supply nutrients, clean up toxins, and support neuron survival.

- Microglia: Act as the CNS’s immune system, cleaning up waste and protecting against infection.

- Oligodendrocytes: Produce myelin, a fatty sheath that wraps around axons to speed up signal transmission

Disorders & Damage

Disorders and damage associated with the CNS range from acute injuries caused by external forces to progressive neurodegenerative diseases and complex psychiatric conditions rooted in biological dysfunction.

Because the CNS controls vital functions, sensation, movement, and cognition, damage to specific areas often results in distinct, sometimes profound, behavioral and functional deficits.

1. Acute Trauma and Vascular Disorders

These disorders involve sudden physical or circulatory failure within the brain.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

TBI results from biomechanical forces—such as blunt impact or rapid acceleration—that deform the brain and vasculature.

- Pathophysiology: Primary injury causes mechanical deformation, while secondary cascades (inflammation/metabolic changes) occur over time.

- Tissue Vulnerability: Damage often occurs at the interface between gray matter (cell bodies) and white matter (axons) due to their different elastic properties.

- Historical Case (Phineas Gage): Damage to his frontal lobe illustrated that this region governs executive function and personality; he became impulsive and irresponsible following his injury.

Cerebrovascular Disorders (Stroke)

A stroke occurs when blood supply is disrupted, leading to cell death.

- Types: Ischemic (blockage) or Hemorrhagic (rupture).

- Localization: Symptoms depend on the affected artery. For example, Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) occlusion causes face/arm deficits and dysphasia, while Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) damage affects the occipital lobe, causing visual deficits.

2. Neurodegenerative Diseases

These conditions involve the progressive loss of neuronal structure or function.

- Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Involves amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to memory loss and shrunken hippocampi.

- Parkinson’s Disease: Degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, causing tremors and difficulty initiating movement.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): An autoimmune disorder causing demyelination in the CNS, which slows or blocks nerve impulses.

- Huntington’s Chorea: A genetic disorder causing degeneration of the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), leading to uncontrollable movements.

3. Complex Processing Disorders (Aphasia & Agnosia)

Damage to “higher-order” association areas of the cortex produces syndromes where sensation remains intact, but recognition fails.

- Broca’s Aphasia: Damage to the left inferior frontal cortex results in halting, laborious speech, though comprehension is often intact.

- Wernicke’s Aphasia: Damage to the left temporal lobe results in fluent but nonsensical “word salad” and poor comprehension.

- Visual Agnosia: Inability to recognize objects despite seeing them, often due to damage in the ventral visual stream.

- Prosopagnosia: Specific inability to recognize faces, linked to lesions in the fusiform gyri.

4. Psychiatric and Developmental Disorders

Biological dysfunctions within brain networks often underpin psychiatric conditions.

- Epilepsy: A disorder of neural excitability. In severe cases, severing the corpus callosum (split-brain surgery) is used to prevent seizure spread, resulting in hemispheres that cannot communicate.

- Schizophrenia: Structural abnormalities include enlarged cerebral ventricles and reduced gray matter in the frontal lobes, often involving dopamine and glutamate imbalances.

- Mood Disorders: Linked to dysfunction in regions regulating emotion, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

How the central nervous system is protected

As the central nervous system is vital for a variety of functions, as well as survival, it is exceptionally well protected.

A skull encases the brain, and the spinal cord runs through the middle of a column of hollow bones known as vertebrae.

The brain and the spinal cord are also protected by a three-layered set of membranes called the meninges (the layers specifically called pia mater, arachnoid, and dura mater).

To ensure the brain and the spinal cord do not come into direct contact with any bones of the skull or vertebrae, they float in a clear liquid called cerebrospinal fluid.

The cerebrospinal fluid fills the space between the two meninges, as well as circulates within the ventricles of the CNS, providing a surrounding cushion to the brain and spinal cord, protecting them from damage.

Protecting the central nervous system

Although many CNS disorders, like Alzheimer’s or multiple sclerosis, may not have a cure, there are ways to reduce risks and support long-term brain and spinal cord health.

Simple ways to protect your CNS:

- Wear safety gear to prevent head and spine injuries during sports, cycling, or driving.

- Stay active—both mentally and physically—to support brain function and circulation.

- Eat a brain-healthy diet, rich in omega-3s, fruits, and vegetables.

- Limit alcohol and avoid harmful substances, which can damage nerve tissue.

- Manage blood pressure and cholesterol to lower the risk of stroke.

- Stay up to date on vaccinations to help prevent infections like meningitis.

Taking care of your nervous system doesn’t mean you can prevent all conditions—but it can help protect what matters most: your ability to move, think, and live independently.

References

Brodal, P. (2004). The central nervous system: structure and function. oxford university Press.

Noback, C. R., Ruggiero, D. A., Strominger, N. L., & Demarest, R. J. (Eds.). (2005). The human nervous system: structure and function (No. 744). Springer Science & Business Media.