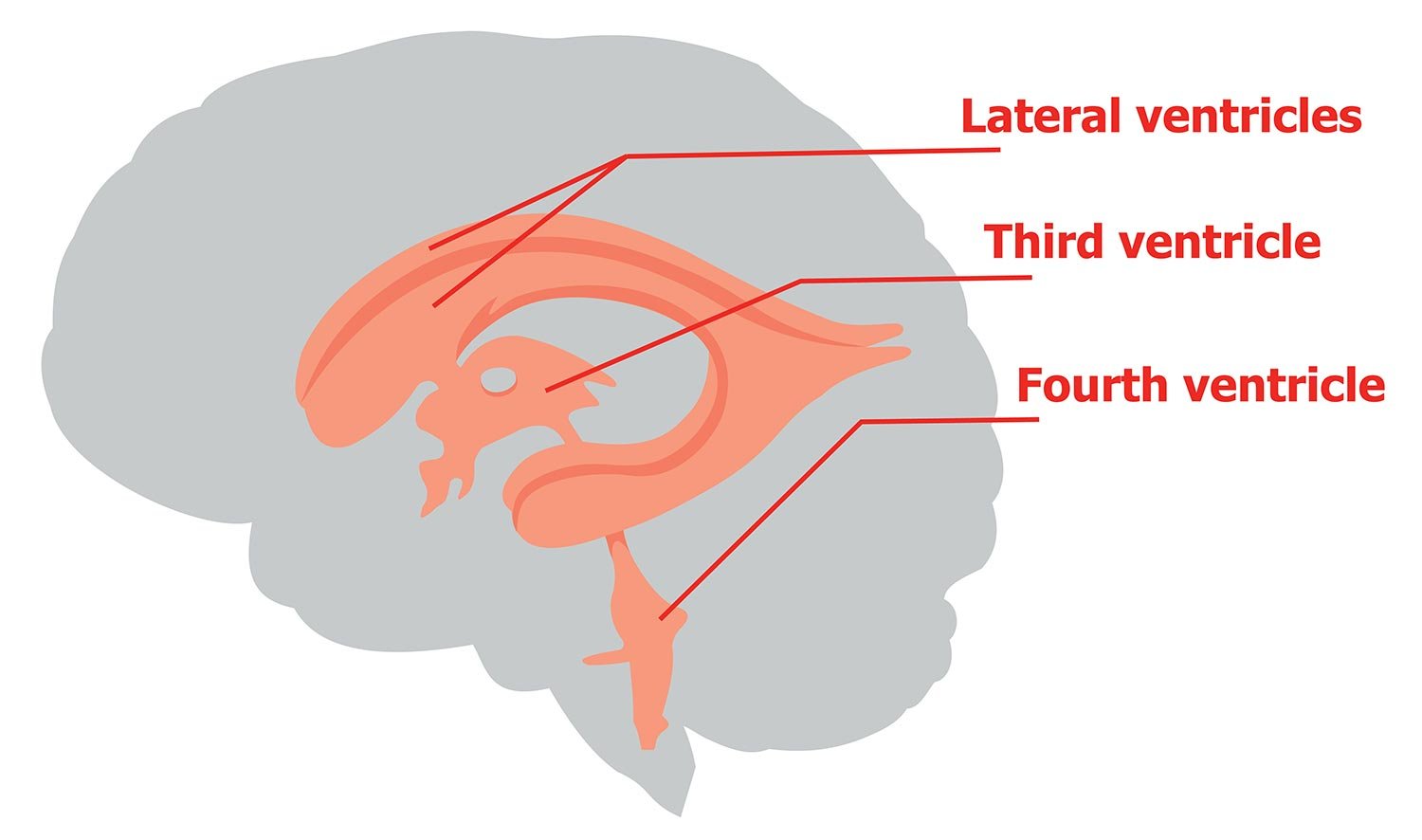

The ventricular system is a closed system within the brain consisting of a series of interconnected, fluid-filled cavities known as ventricles.

These ventricles contain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which circulates through the brain and spinal cord, acting as a support system for the central nervous system.

Circulate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cushions the brain, removes waste, delivers nutrients, and maintains internal pressure.

Lateral Ventricles (1 & 2)

The lateral ventricles are the largest components of the brain’s internal fluid system.

These are two channels that bifurcate (branch) and enlarge within the cerebrum. They are the largest of the ventricles and connect directly to the third ventricle.

Anatomy (C-Shaped)

Rather than being simple circles, the lateral ventricles are expansive and reach into different territories of the brain via their horns:

- Anterior Horn: Extends into the Frontal Lobe (involved in planning and personality).

- Posterior Horn: Extends into the Occipital Lobe (involved in vision).

- Inferior Horn: Extends into the Temporal Lobe (involved in memory and language).

The Biological Function

The lateral ventricles are the starting point for the brain’s “irrigation” system.

- Primary Production: These ventricles contain the largest volume of choroid plexus. This tissue acts as a biological filter, constantly turning blood plasma into the nutrient-rich, shock-absorbing CSF.

- Flow Dynamics: As CSF is produced, it creates a pressure gradient that pushes the fluid through the Interventricular Foramen (the “doorway”) into the Third Ventricle.#

- Waste Clearance: The flow of CSF from these ventricles into the third ventricle (via the Foramina of Monro) acts like a constant “flush,” clearing metabolic byproducts from deep brain structures.

Third Ventricle

The third ventricle is a narrow midline chamber located between the two halves of the thalamus.

It is a thin, slit-like cavity that sits perfectly in the midline, acting as a vital junction for both fluid circulation and hormonal regulation.

Because the third ventricle is so narrow, any enlargement is highly visible on an MRI and serves as a “red flag” for the loss of surrounding tissue.

While the lateral ventricles are expansive, the third ventricle is remarkably narrow. Its importance comes from its “neighbors” – the structures that form its walls.

Anatomical Boundaries & “Neighborhood”

The third ventricle is the heart of the diencephalon. Its boundaries are made up of the most important regulatory centers in the brain:

- The Walls: Formed by the Thalamus (the brain’s relay station) and the Hypothalamus (the command center for hormones and survival).

- The Floor: Formed mainly by the hypothalamus and the infundibulum (the stalk of the pituitary gland).

- Communication Lines: Inlet: Receives CSF from the lateral ventricles via the Foramina of Monro. Outlet: Channels CSF into the midbrain through the Cerebral Aqueduct.

Physiological Significance: Thirst and Homeostasis

The third ventricle is more than a hallway for fluid; it is a “sensing station.”

- The OVLT (Organum Vasculosum of the Lamina Terminalis): This structure sits in the anterior wall of the third ventricle. Because it lacks a strict blood-brain barrier, it can “taste” the blood to check for saltiness.

- Osmometric Thirst: When you are dehydrated, the OVLT detects the rise in salt concentration and signals the hypothalamus to trigger the sensation of thirst.

- Choroid Plexus & Blood Supply: The roof of the third ventricle contains a strip of choroid plexus supplied by the Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA), contributing to the continuous production of fresh CSF.

Fourth Ventricle

The Fourth Ventricle is the “grand terminal” of the brain’s internal plumbing.

It is the final chamber where Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) is collected before it is released to bathe the exterior of the brain and the spinal cord.

Located in the brainstem, posterior to the pons.

It has three openings Foramina of Luschka and Magendie) that allow CSF to exit the ventricles and enter the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain.

Anatomy

The fourth ventricle is famously diamond-shaped when viewed from behind. It is tucked into a very crowded and important neighborhood in the hindbrain:

- The Floor (Anterior): Formed by the pons and the medulla oblongata. These areas control vital life functions like breathing and heart rate.

- The Roof (Posterior): Formed by the cerebellum, which coordinates balance and fine motor skills.

- The Pillars: The side walls are formed by the cerebellar peduncles, the massive nerve “cables” that connect the cerebellum to the brainstem.

The “Gateway” Function: Flow and Drainage

The fourth ventricle is the only part of the system that allows fluid to escape the “internal” brain and reach the “external” surface.

- Inlet: Receives CSF from the midbrain via the Cerebral Aqueduct.

- Outlets (The Foramina): This is where the fluid exits into the subarachnoid space:

- Foramen of Magendie (Median Aperture): A single opening in the middle that directs fluid toward the spinal cord and brainstem.

- Foramina of Luschka (Lateral Apertures): Two openings on the sides that direct fluid around the brain.

- Blood Supply: Its choroid plexus is supplied by the PICA (Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery). A stroke in this artery can damage the fourth ventricle and the cerebellum simultaneously.

Cerebral Aqueduct

The Cerebral Aqueduct, also known as the Aqueduct of Sylvius, is a narrow channel located within the midbrain that connects the thrid and forth ventricles

This tiny channel, usually only 1-2 mm in diameter, is the only way for Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) to reach the lower brain and spinal cord.

It is a critical component of the brain’s ventricular system, allowing for the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) between the central and hindbrain regions.

Anatomical Location and Flow

The aqueduct is located deep within the Mesencephalon (midbrain).

- The Bridge: It connects the Third Ventricle (above) to the Fourth Ventricle (below).

- Structural Borders: It is sandwiched between the Tectum (the “roof” of the midbrain, which handles visual and auditory reflexes) and the Tegmentum (the “floor,” which handles motor and sensory functions).

Functional Connectivity

The third ventricle is a high-traffic zone for Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF).

- Inflow: CSF enters from the Lateral Ventricles through the Interventricular Foramina (Foramina of Monro).

- Outflow: CSF exits via the Cerebral Aqueduct, a tiny canal that leads to the Fourth Ventricle.

- Neuroendocrine Link: Because the ventricle has recesses reaching toward the pituitary and pineal glands, it allows for the transport of signaling molecules and hormones directly into the fluid system.

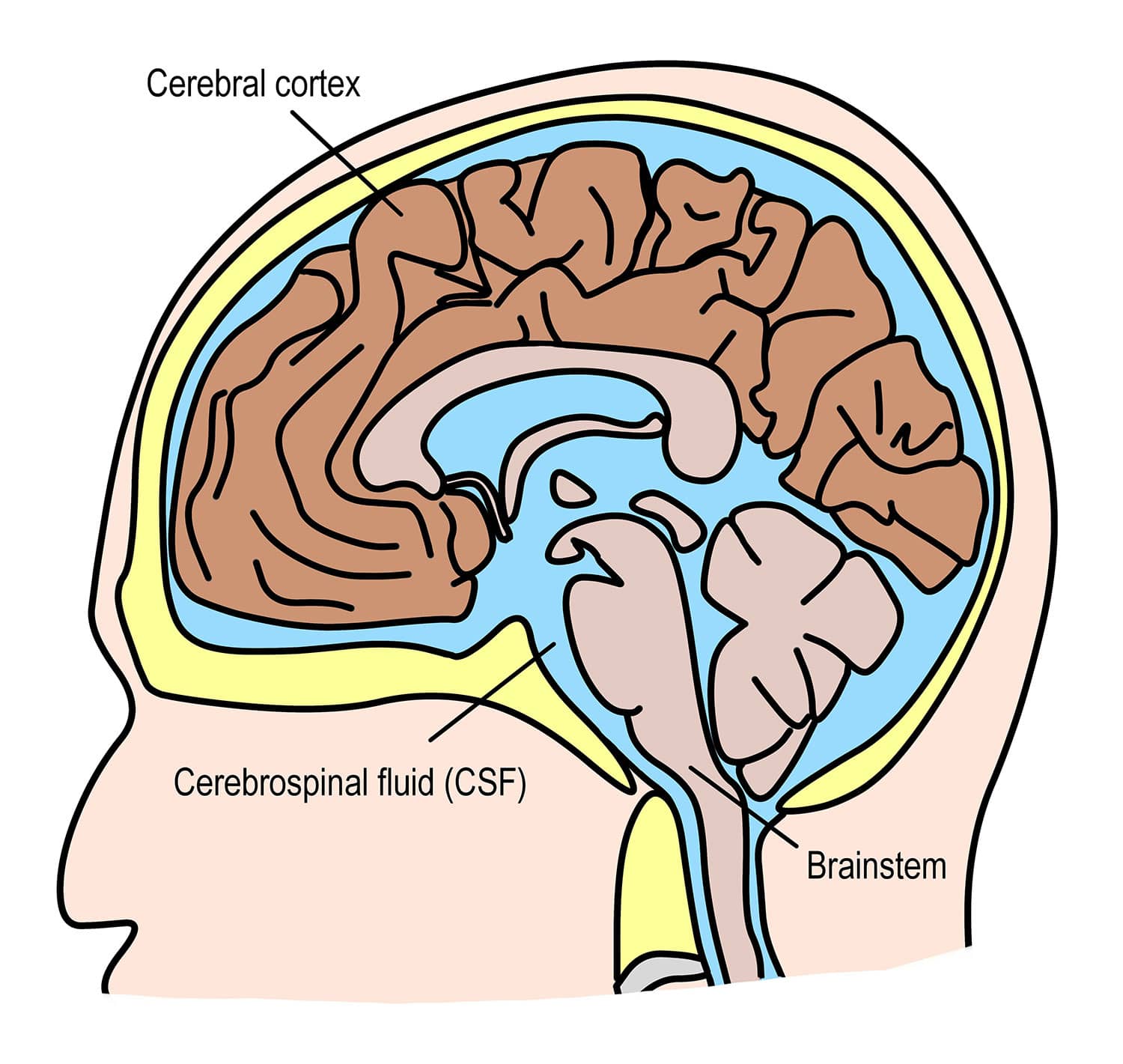

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, water-like liquid that flows continuously through the brain’s ventricles and around the spinal cord.

It’s mainly produced by filtering plasma from the blood at the choroid plexus. On average, the human body produces about half a liter of CSF each day.

- Production: CSF is primarily produced by the choroid plexus (tissue lining the ventricles), as well as by ependymal cells and blood vessels of the brain and spinal cord.

- Composition: The fluid consists of water, protein, glucose, and various ions (sodium, potassium, and chloride), along with oxygen and carbon dioxide

Although the brain is protected by the skull and three meninges (dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater), there is still space within the skull that could allow the brain to shift or sustain injury.

CSF fills these spaces, providing additional protection and stability.

Functions of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Beyond just “filling space,” CSF is active in every aspect of brain survival:

- Buoyancy: Reduces the brain’s effective weight from 1400g to ~50g, preventing it from crushing its own blood vessels. Without this flotation, the heavy weight of the brain would cut off its own blood supply at the base of the skull.

- Shock Absorption: Acts as a hydraulic cushion against physical impact. The fluid layers absorb and spread the kinetic energy from a blow to the head, preventing the delicate neural tissue from striking the hard interior of the cranium.

- Nutrient Delivery: Distributes glucose, proteins, lipids, and electrolytes. Because the brain has a high metabolic demand, the CSF acts as a secondary delivery system to ensure every neuron receives the “fuel” it needs to fire action potentials.

- Waste Removal: Flushes metabolic byproducts (like $\beta$-amyloid) into the venous system. This “glymphatic” flushing occurs most effectively during sleep, preventing the buildup of toxic proteins that are linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

- Pressure Regulation: Buffers changes in intracranial blood volume. By shifting in and out of the skull and spinal canal, the CSF can compensate for changes in blood pressure to keep the total volume inside the skull constant.

- Temperature Control: Distributes heat generated by high metabolic activity in deep brain structures. The constant circulation of the fluid helps “wick away” excess heat from the core of the brain, maintaining a stable thermal environment for sensitive enzymes.

- Immune Defense: Contains leukocytes (white blood cells) that monitor for infection. The CSF acts as a patrolling ground for the immune system, allowing it to quickly identify and attack bacteria or viruses that manage to cross the blood-brain barrier.

What Happens When the Ventricular System Fails?

In a healthy brain, the ventricular system is a “closed, pressurized circuit.”

When this system fails due to trauma, disease, or blockage, it shifts from a support system to a diagnostic marker of brain damage.

Disruption in the production, flow, or reabsorption of CSF can cause serious medical issues. Below are common conditions linked to ventricular system dysfunction:

1. Structural Distortion & Space-Occupying Lesions

In acute trauma, the ventricles are the first structures to show distress because they are fluid-filled and “compressible.”

- Midline Shift: In a healthy brain, the ventricles are symmetrical. A hemorrhage (bleeding) creates a “mass effect,” pushing brain tissue and the ventricles across the center line of the skull. This is a critical medical emergency.

- Compression: High intracranial pressure (from swelling or edema) can flatten the ventricles into tiny “slits,” indicating that the brain is being squeezed against the skull.

For a professional teacher’s handout, it is helpful to organize these “failures” into a clear, comparative format. Since you are a novice, this structure helps bridge the gap between basic anatomy and clinical diagnosis by using the “Fixed-Box” principle (the idea that the skull is a rigid container with no room for extra volume).

Pathology of the Ventricular System: When the System Fails

When the ventricular system fails—due to trauma, disease, or blockage—it stops being a support system and starts becoming a diagnostic indicator of brain damage.

1. Structural Distortion & Space-Occupying Lesions

In acute trauma, the ventricles are the first structures to show distress because they are fluid-filled and “compressible.”

- Midline Shift: In a healthy brain, the ventricles are symmetrical. A hemorrhage (bleeding) creates a “mass effect,” pushing brain tissue and the ventricles across the center line of the skull. This is a critical medical emergency.

- Compression: High intracranial pressure (from swelling or edema) can flatten the ventricles into tiny “slits,” indicating that the brain is being squeezed against the skull.

2. Passive Dilation: Hydrocephalus ex Vacuo

This is “dilation by default.” It occurs when the ventricles enlarge not because of pressure, but because the surrounding brain tissue has shrunk.

- Mechanism: As neurons die (atrophy) or tissue softens (encephalomalacia), the ventricles expand to fill the empty space. This is a “passive” failure of volume maintenance.

- Disease Biomarkers: * Schizophrenia: Enlargement of the Third Ventricle is seen in 80% of cases, reflecting a loss of gray matter in the frontal lobes and limbic system.

- Neurodegeneration: General ventricular enlargement is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s and long-term Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).

3. Active Dilation: Obstructive Hydrocephalus

This is a “plumbing” failure where fluid builds up behind a blockage.

- Mechanism: A physical block (like a tumor or a narrow Cerebral Aqueduct) prevents CSF from moving to the next ventricle.

- Pressure Imbalance: Because the Choroid Plexus continues to produce fluid, the pressure rises behind the block, “ballooning” the ventricles and crushing the surrounding brain tissue.

- Absorption Failure: If the Arachnoid Villi (the exit valves) are damaged, fluid cannot return to the venous system, causing global pressure across the entire brain.

References

Neuroscientifically Challenged. (2015, February 1.). Know Your Brain: Ventricles. https://neuroscientificallychallenged.com/posts/know-your-brain-ventricles

Crumble, L. (2021, October 28). Ventricles of the brain. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/ventricular-system-of-the-brain

Vega, J. (2021, October 21). The Anatomy of the Brain Ventricles. Very Well Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/brain-ventricles-3146168

Jones, O. (2020, November 13). The Ventricles of the Brain. Teach Me Anatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/neuroanatomy/vessels/ventricles/