The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all nerves outside the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system), acting as a communication relay between the CNS and the rest of the body.

It enables movement, sensation, and involuntary functions like heart rate and digestion.

What does the PNS do?

The PNS has many essential functions throughout the body:

- Sensation: Sensory information is carried from the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin to the brain. For example, when you smell food, this information is carried from the nose to the brain.

- Movement: The PNS carries signals that allow for voluntary movements such as walking, and maintaining posture, and for reflex movements such as automatically moving a hand away from a hot surface.

- Involuntary processes: Vital, unconscious processes such as heartbeat and breathing are controlled by the PNS.

- Digestion: The PNS sends messages to the digestive system to keep food moving along, for example, by helping to produce saliva when food is presented.

The functions of the PNS are controlled by different substructures which will be explained in the next section.

Parts and Divisions of the Peripheral Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is divided into two main branches, each with distinct roles:

These subdivisions help regulate both voluntary and involuntary body functions.

Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system is responsible for conscious, voluntary movements, like walking, talking, or typing.

It includes two types of nerves:

- Sensory neurons (afferent neurons): Carry information from sensory organs (skin, eyes, ears, etc.) to the central nervous system (CNS).

Example: When you touch a hot stove, sensory neurons alert the brain. - Motor neurons (efferent neurons): Transmit signals from the CNS to skeletal muscles, enabling movement.

Example: Your brain sends motor commands that help you lift a cup or run.

This system also controls reflex actions through a structure called the reflex arc, which allows for fast, automatic responses without involving the brain.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system manages involuntary processes—functions you don’t consciously control, like heartbeat, digestion, or breathing. It is further divided into two parts:

- Sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight):

Prepares the body for stressful situations. It increases heart rate, opens airways, dilates pupils, and slows digestion. - Parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest):

Calms the body after stress. It reduces heart rate, promotes digestion, and restores energy balance.

Together, the SNS and ANS allow the PNS to handle both physical movement and automatic life-sustaining processes.

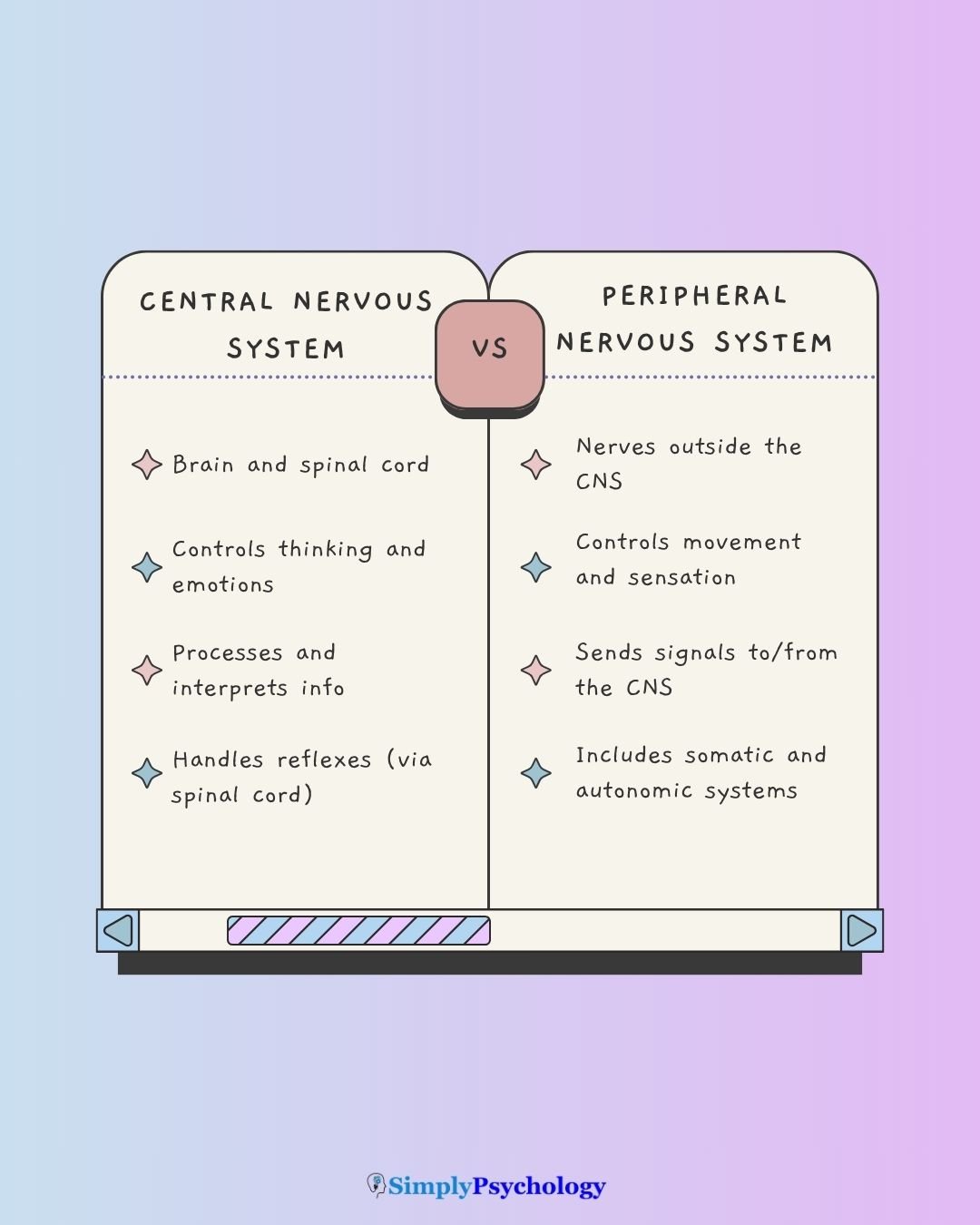

Central nervous system vs peripheral nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) serve distinct but complementary roles.

The CNS, consisting of the brain and spinal cord, acts as the body’s command center and is protected by bone and protective membranes.

The PNS comprises nerves branching throughout the body, lacking bony protection and thus more vulnerable to injury.

While the CNS processes and makes decisions, the PNS functions as a messenger network through sensory and motor neurons.

CNS neurons also have limited regenerative capacity, making injuries often permanent.

PNS neurons, however, can regenerate under certain conditions, allowing for potential recovery from peripheral nerve damage.

Nerves in the Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is made up of nerve cells (neurons) that carry messages back and forth between the CNS and the muscles, organs, and senses in the body’s periphery.

Within the PNS, some nerves are attached to the spinal cord (spinal nerves), and others are attached directly to the brain (cranial nerves).

Spinal nerves

There are 31 pairs of spinal nerves, which emerge from the spinal cord and branch out to serve different areas of the body. These nerves carry:

- Sensory signals from the skin, muscles, and organs to the spinal cord and brain

- Motor commands from the brain and spinal cord to the muscles and glands

Types of spinal nerves (grouped by region):

- 8 cervical nerves, which serve the chest, head, neck, shoulders, arms, and hands (called C1-C8).

- 12 thoracic nerves, which serve the back, abdominal muscles, and intercostal muscles (called T1 – T12).

- 5 lumbar nerves, which serve the lower abdomen, thighs, and legs (called L1-L5).

- 5 sacral nerves, which serve the legs, feet, and genital areas (called S1-S5).

- 1 coccygeal pair of nerves (called Co1).

These nerves exit the spinal column through openings in the vertebrae and form a vast network that links every part of the body to the nervous system.

Example: The Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic nerve, which extends from the lower spine down to the toes, is the longest nerve in the human body.

It plays a major role in leg movement and is commonly associated with conditions like sciatica.

Cranial nerves

Unlike spinal nerves, cranial nerves connect directly to the brain, bypassing the spinal cord.

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves, and most are involved in sensory and motor functions of the head and neck.

Functions of Cranial Nerves:

- Transmit sensory input from the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and face

- Send motor signals to muscles involved in facial expression, chewing, swallowing, and speech

For example, when eating:

- Cranial nerves help you chew and swallow (motor function)

- They also relay taste signals back to the brain (sensory function)

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves attached to the brain:

- Olfactory nerves are sensory nerves related to the sense of smell.

- Optic nerves are sensory nerves related to the sense of sight.

- Oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves are motor nerves responsible for regulating voluntary eye movements.

- Vestibulocochlear nerves are sensory nerves related to the sense of hearing, linked with sound, orientation, and balance.

- Glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves are sensory and motor nerves responsible for tongue muscle movements and sense of taste.

- Vagus nerves are both sensory and motor nerves responsible for movements of the lower head, throat, neck, chest, and abdomen, as well as autonomic functions such as breathing and heart rate.

- Spinal accessory nerves are both sensory and motor nerves responsible for the muscle and movements of the head, neck, and shoulders.

- Facial nerves are sensory and motor nerves related to the taste buds and movements of the face (facial expressions).

- Trigeminal nerves are sensory and motor nerves that carry signals from the eyes, teeth, and face, as well as impulses from the lower jaw and muscles involved with chewing.

Why the Peripheral Nervous System Matters

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is not just a conduit for signals between the brain and body; it’s a dynamic network essential for survival, adaptation, and overall well-being.

1. It Powers Everyday Actions

The PNS lets you walk, grip a pencil, feel textures, or react quickly to danger.

These responses happen through sensory and motor nerves working in sync with the brain and spinal cord.

2. It Keeps Your Body in Balance

The autonomic division of the PNS regulates involuntary processes like heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion.

This helps maintain homeostasis—your body’s internal balance—even during stress or illness.

3. It Can Regenerate After Injury

Unlike the central nervous system, the PNS has some ability to repair itself.

Cells like Schwann cells help guide the healing of damaged nerves, improving chances of recovery after injury.

4. It Reflects Your Overall Health

Tingling, numbness, or muscle weakness may indicate larger issues like diabetes, autoimmune disorders, or nutritional deficiencies.

Tracking PNS symptoms can support early diagnosis of systemic problems.

5. It Includes the “Second Brain”

The enteric nervous system, part of the PNS, controls digestion independently of the brain.

It’s so influential that scientists call it the “second brain.”

It even plays a role in mood regulation and immune function.

Sources

Dorland, W. A. N. (2011). Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Eyesenck, M. W. (2012). Simply Psychology. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Goldstein, D. S. (2010). Adrenal responses to stress. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 30 (8), 1433-1440.

Martin, G. N., Carlson, N. R., & Buskist, W. (2009). Psychology, 4th European edition. Harlow: Pearson Education, 723-725.