Many people with anxiety experience mental rumination – getting stuck in a repetitive thought loop that seems impossible to escape.

Take heart: rumination is a common human habit, especially for those of us prone to anxiety. In fact, it often feels like you’re doing something useful – as if by endlessly dissecting the problem, you’ll eventually find relief or prevent something bad.

The truth, however, is that rumination typically backfires and fuels more anxiety, keeping you locked in distress. The good news is that this is a habit you can learn to change.

What is rumination?

Rumination is a pattern of repetitive, unproductive thinking. When you ruminate, you aren’t brainstorming solutions or reflecting calmly – instead, you’re dwelling on the same distressing thoughts without getting new insight.

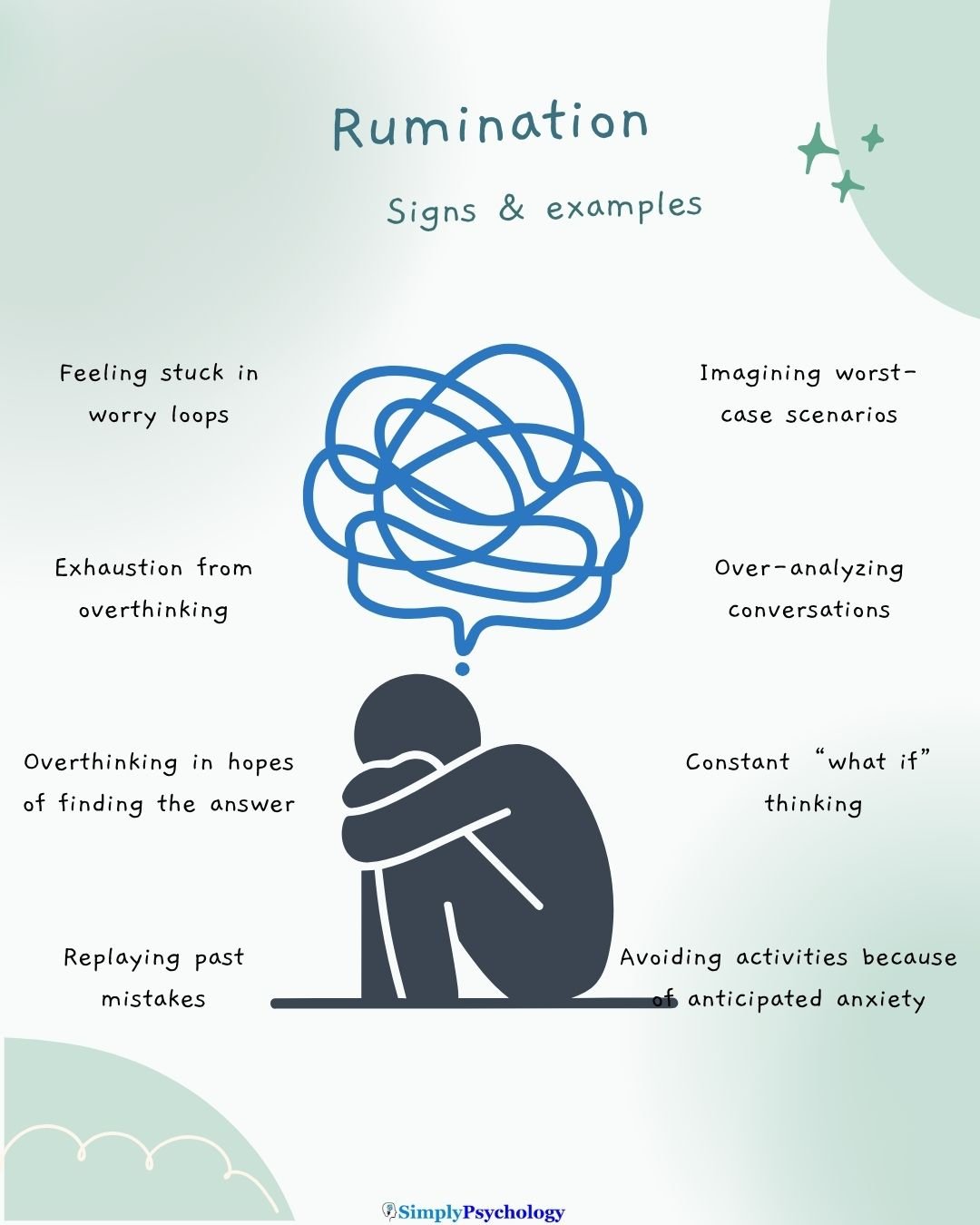

Unlike productive reflection, rumination doesn’t lead to insight or action — it just loops. You might find yourself:

- Replaying conversations to analyze what you said “wrong”

- Mentally rehearsing how you’ll handle future problems

- Obsessing over what someone might think of you

In other cases, rumination can center on “what if” scenarios – continually imagining hypothetical situations where things go wrong.

The key features of rumination are that it’s intrusive (the thoughts force their way in), repetitive (the same tape playing on repeat), and unproductive (you don’t arrive at new solutions or peace of mind).

Why Rumination Feels Like Control — But Isn’t

If you ruminate, it’s probably because on some level it feels useful or necessary. You might believe that by mentally replaying or dissecting a problem, you’ll prevent future mistakes or finally “figure it out.”

In the moment, rumination can create an illusion of control – as if thinking harder about the issue will eventually make you feel prepared or certain. “Maybe if I revisit this one more time, I’ll feel better about it,” we tell ourselves.

“People who ruminate continue to do so because they feel they’ll gain hoped-for insight into a vexing problem. In essence, your brain is tricking you into believing you’re figuring out something useful. But it’s usually a trap: thinking endlessly about a problem often doesn’t solve anything — it just proves exhausting, stealing your focus from things you’d rather be doing.”

Dr Jacquelline Ods, Psychiatrist

The hard truth is that rumination rarely delivers the relief or solutions it promises.

It is counterproductive: it keeps your mind in “analysis mode” without leading to action or resolution, all while draining your mental and emotional energy.

How rumination fuels anxiety: The vicious cycle

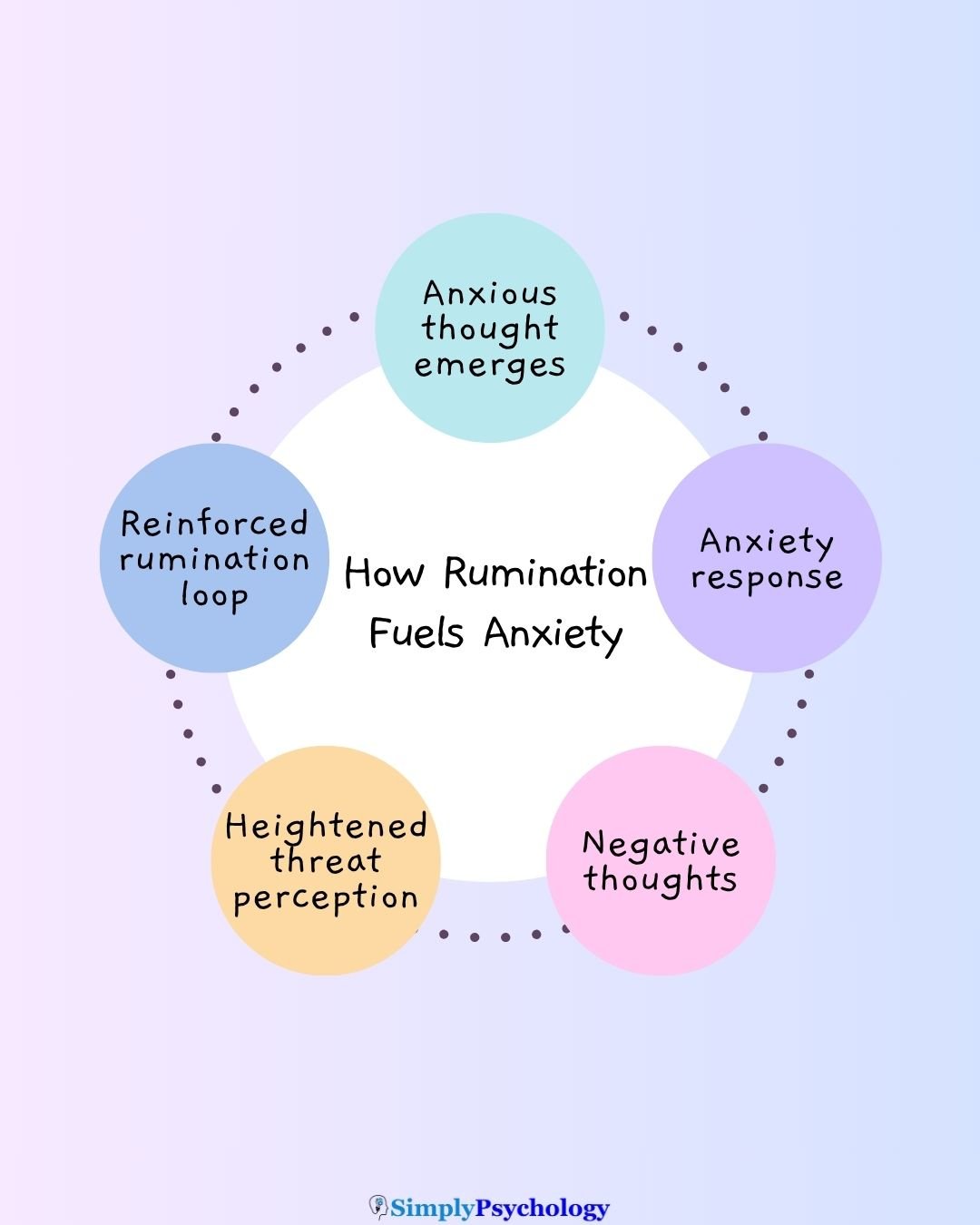

Not only is rumination unhelpful, it actively intensifies anxiety, keeping you in threat mode.

When an anxious thought gets stuck on repeat, it triggers anxious feelings in your body and keeps your stress response activated – racing heart, tense muscles, that pit in your stomach.

And once your body is in alert mode, those physical sensations (and the stress hormones like cortisol surging through your system) feed more worrisome thoughts.

It becomes a vicious cycle: thought → anxiety → more thoughts → even more anxiety.

Ruminative thoughts tend to snowball (“I know I messed up that presentation… now everyone must think I’m incompetent… I’ll probably get fired…”), which amplifies anxiety, reinforces negative beliefs and magnifies perceived threats.

Rumination can create an insidious loop between anxiety and depression: feeling anxious or down leads to more rumination, which then makes those feelings worse which is hard to break.

You can’t think your way out of it (and that’s not a failing)

Many people with anxiety are very aware that they’re overthinking – they might even chastise themselves for it – yet they feel unable to stop.

You can’t simply out-think rumination because rumination is a thinking trap.

Telling yourself “Stop worrying!” on repeat is like yelling at an echo; it just keeps bouncing back.

As one individual put it, “I can see it happening and I tell myself to just drop it until morning, but it doesn’t work”.

Insight alone (however logical) often isn’t enough to halt the cascade of thoughts and anxious feelings once your nervous system is keyed up.

Rather than blaming yourself for “overthinking again,” recognize that this is a common human experience, especially for those of us with anxiety.

You’re not failing – you simply need a different approach to get out of the mental loop, one that doesn’t rely on more thinking.

Strategies to help with rumination

You can’t force rumination away, but you can learn to interrupt it or exit the loop in healthier ways. Here are 9 techniques, drawn from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and other research-backed approaches:

1. Behavioral Activation – Move into action, however small.

Deliberately do something concrete and simple – preferably something active or requiring focus. For example, stand up and stretch, take a quick walk, tidy a small area of your room, or put on music and sing along.

Taking even a tiny action helps redirect your attention outward, back into the real world.

Behavioral activation is a known antidote to depressive rumination because it breaks the inertia; you prove to your brain that you can affect things (unlike a thought loop which achieves nothing).

The next time you catch yourself spiraling mentally, ask: “What’s one small thing I can do right now?”

2. Self-Distancing via Journaling – Write about your thoughts in the third person.

Analyzing your feelings from a slight distance (like an outside perspective) may dramatically reduce emotional overwhelm and rumination.

Instead of journaling “I’m so anxious about X… I don’t know what to do,” try writing as if you’re observing yourself or someone else: e.g., “She is feeling anxious about X because…”.

You can even use your own name: “<Your Name> is worrying that…”. It might feel odd at first, but studies have found this simple shift in language helps people gain perspective.

By writing about yourself as “he/she/they”, you essentially step into an observer role – it creates a mental gap between you and the anxious thought. That gap allows you to be more objective and compassionate, almost as if you were writing about a friend.

3. Name the Thought Pattern (ACT Defusion) – Label your mental story for what it is.

This involves acknowledging thoughts as thoughts, not as absolute truths. A simple defusion exercise is to literally name the ruminative thought when it shows up.

For example, if you catch yourself mentally criticizing yourself (“I messed up again, I’m a failure”), you pause and say (in your mind or aloud): “Ah, here’s the ‘I always mess up’ story again.” Or “I’m having the thought that I’m a failure right now.”

This little phrase – “I’m having the thought that…” – is powerful. It instantly reminds you that a thought is just a mental event, not reality.

Over time, this helps weaken the grip of common rumination themes.

4. Somatic Grounding Techniques – Use your body to break the mental loop.

Rumination often pulls us out of the present and up into our heads, so doing something physical can anchor you back to the here-and-now.

Grounding techniques engage the senses or the body’s reflexes to disrupt racing thoughts:

- Splash cold water on your face or hold an ice cube for a few seconds to shift focus to the body.

- Rhythmic exercise, such as a short workout, 20 jumping jacks, or dancing to an upbeat song.

- 5-4-3-2-1 sensory scan: look around and name 5 things you see, 4 things you can feel (your clothing on skin, the ground under your feet), 3 things you hear, 2 you can smell, 1 you can taste.

- Breathing exercises such as inhaling for 4 counts, exhaling for 6-8 counts.

These methods can help to force the mind to engage with your immediate environment and to help burn off anxious energy.

5. “Drop Anchor” (ACT Method) – Ground yourself with the ACE technique.

“Dropping anchor” is a quick skill from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy designed to help you center yourself when caught in a storm of thoughts and feelings.

Imagine you’re a boat being tossed by huge waves (your overwhelming thoughts); dropping anchor won’t stop the storm, but it will keep you stable until it passes.

To drop anchor, remember the acronym A.C.E.:

- Acknowledge what you’re feeling and thinking in the moment – notice and name the thoughts or emotions (e.g., “I’m noticing that I’m worrying about tomorrow’s meeting and feeling dread in my chest”).

- Come back into your body – re-ground yourself physically. For example, plant your feet firmly on the floor, straighten your back, and take a slow, controlled breath (feel the air filling your lungs).

- Engage with the present by focusing your attention on the here and now: look around and notice your surroundings, or resume whatever task you were doing with full attention.

6. The STOP Skill (DBT) – Interrupt the loop with a mindful pause.

STOP is a skill from Dialectical Behavior Therapy that’s excellent for those moments when you feel yourself getting mentally carried away.

STOP is an acronym that stands for Stop, Take a step back, Observe, Proceed mindfully:

- S = Stop. Literally, stop what you’re doing (and stop following the racing thoughts). Freeze for a moment.

- T = Take a step back from your mind. This can be literal (e.g., step away from your desk) or figurative (mentally say “halt”). Take a breath. The idea is to pause the automatic reaction.

- O = Observe. Notice what’s going on – both around you and inside you. What thoughts are looping? What are you feeling in your body? Just observe it all like a curious bystander, without judgment.

- P = Proceed mindfully. With this slightly clearer head, choose your next action consciously. Maybe you decide, “I’m going to step outside for five minutes,” or “I’ll finish this email slowly and breathe.”

The STOP skill basically inserts a circuit breaker in the middle of rumination. Instead of unconsciously reacting to your worried thoughts (and getting more anxious), you deliberately pause and then respond with awareness.

7. Compassionate Reframing – Respond to yourself like you would to a friend.

To break the self-criticism cycle, practice self-compassion in the moments you notice you’re ruminating.

You can ask: “What would I say to my best friend if they were stuck in this same worry?” Then, try saying that to yourself.

For example, instead of “There I go, overthinking again, what’s wrong with me?”, you might tell yourself, “I’m really wound up because I care about this situation. It’s understandable that I’m anxious. I’m not alone; many people go through this.”

You’re not sugarcoating the issue, but you are reframing the narrative to be gentler and more realistic.

8. Scheduled “Worry Time” – Postpone and contain your rumination.

How it works: you designate a daily window for worrying, say 15 minutes in the late afternoon. If anxious thoughts come up earlier in the day, you tell yourself, “I’ll deal with this during my 5:30 worry time.”

You might jot down a keyword to remember it, then redirect your attention to the present task.

At first, your brain will resist (“No, we must obsess now!”), but with practice it learns that there’s a later appointment for that concern.

When the scheduled time arrives, you intentionally allow yourself to worry and ruminate on whatever comes up – but only for that limited period.

When time’s up, you gently stop and move on (perhaps use a timer). This technique works in two ways: it validates your mind’s desire to think about the issue (so you’re not just repressing it), but it also puts a boundary around it.

9. Imagery Replacement – Change the mental channel.

Try a technique of conscious imagery replacement. Think of it like switching the movie that’s playing in your mind.

First, notice what image or scene is looping – what are you seeing when you ruminate?

Next, deliberately choose a different image to focus on. It can be anything calming or even absurd: imagine a peaceful beach at sunset, or visualize a stop sign, or picture a funny memory in vivid detail.

The moment you catch the negative image replaying, pause and swap in your chosen image. You may have to do this repeatedly (just like thoughts, the old image will try to return), but keep replacing it.

Quick Recap: Strategies to Break the Rumination Cycle

- Ground yourself in the present: Use your senses, deep breathing, or body movements to come out of your head.

- Interrupt the loop: Try techniques like “Stop – Take a breath – Observe – Proceed” or dropping anchor when you feel an anxious spiral starting.

- Shift your perspective: Write in third person, name your mental story, or ask what you’d tell a friend to get a more objective and kinder view.

- Take action or redirect: Do a small activity (behavioral activation) or schedule a specific “worry time” later so that rumination doesn’t take over your day.

- Practice self-compassion: Respond to yourself with understanding, not criticism. Remind yourself that it’s okay to feel how you feel, and you’re taking steps to help yourself.