Many people with anxiety share that they sometimes “question everything, even [their] own core beliefs and reality,” as one forum user put it.

Stress and fear prime our minds to grasp for answers, even unreliable ones. In fact, research during recent crises found that rumors and “alternative truths” thrive in environments of high anxiety and low trust.

This means that when we’re anxious or overwhelmed, we’re actually more vulnerable to latching onto beliefs that aren’t accurate, simply because they offer a sense of certainty.

Anxiety and chronic worry can blur the line between real and imagined threats, making it genuinely harder to tell what’s real. Our minds are doing their best to protect us, even if they sometimes protect us in the wrong way.

Key Takeaways

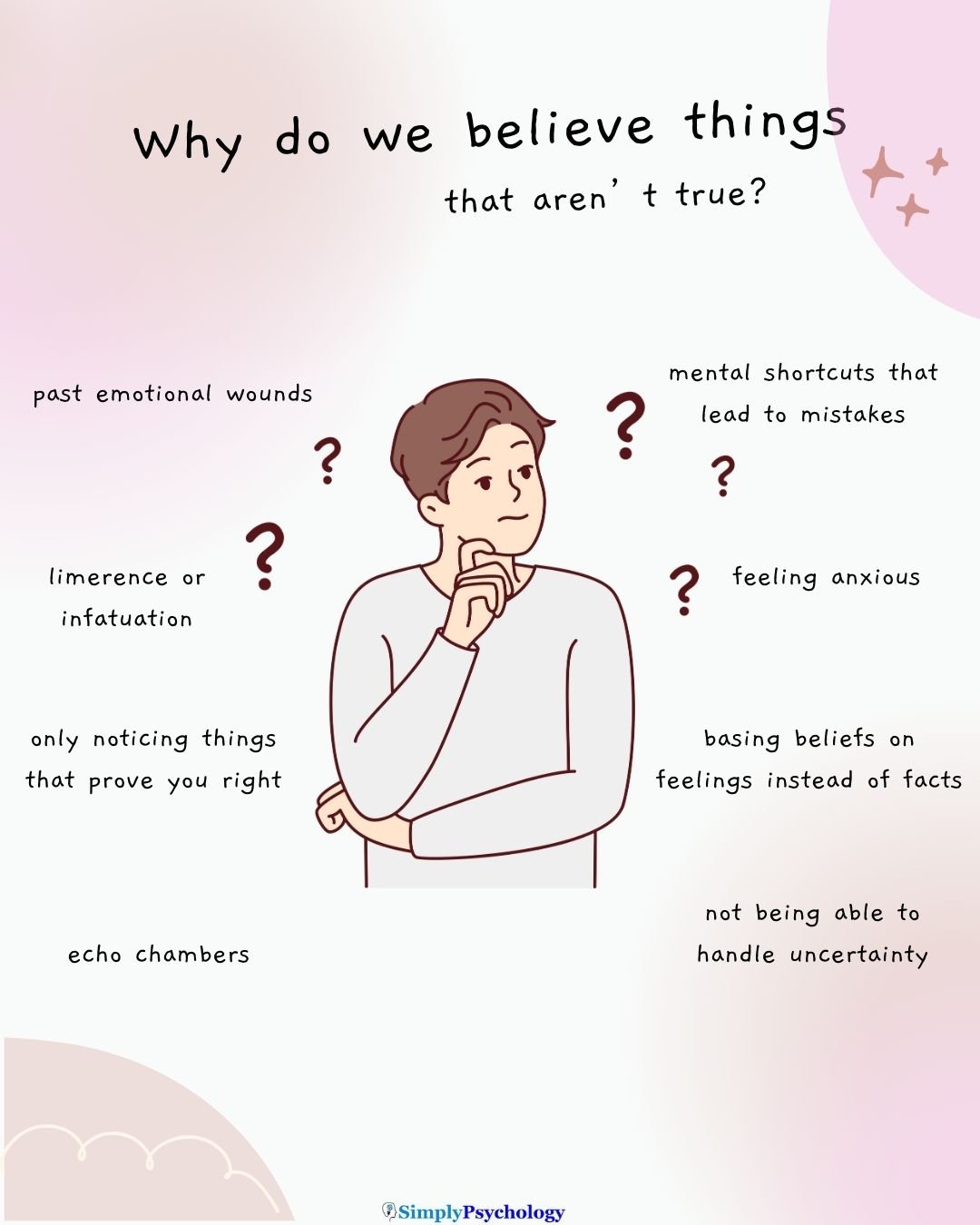

- Believing something untrue is a normal human experience, especially when the brain seeks certainty under stress.

- Strong emotions, particularly anxiety, can make feelings seem like facts, while social pressures and echo chambers reinforce false beliefs.

- Cognitive biases and imperfect memory shape our perceptions, often without us realizing it.

- Simple techniques like examining evidence, considering alternatives, and practicing mindfulness can help challenge inaccurate thoughts.

- If a belief causes distress or disrupts daily life, professional support can provide tools and perspective to break the cycle.

How the Brain Builds Beliefs

Beliefs are like mental shortcuts—quick ways for our brains to make sense of the world. The brain craves certainty and predictability; it would rather have a clear (even if flawed) explanation than cope with uncertainty.

Memory also plays a big role. We often think of memory as a perfect recording of the past, but it’s not. Psychologists note that memory is reconstructive—we piece together fragments of experiences, feelings, and past knowledge to form a coherent story.

We rely on schemas, mental shortcuts, and constructions to help us navigate life efficiently. They’re the reason we don’t have to relearn reality every morning—our brain uses what it already knows (or thinks it knows) to guide our beliefs about each new day.

However, the same shortcuts can mislead us. Our need for quick answers and our imperfect memory can cause us to form beliefs that feel right in the moment, but aren’t actually true.

Understanding this is key: your brain isn’t “lying” to you on purpose; it’s trying to help by creating certainty and drawing on past patterns. Sometimes it just gets things wrong.

The Cognitive Biases That Trip Us Up

Even the best brains get tripped up by cognitive biases—systematic errors in how we think. These biases act like mental filters, making us notice some things and ignore others.

Here are a few common culprits that can lead us to believe false things:

Confirmation Bias

We tend to seek out or recall information that confirms what we already believe, while overlooking evidence that contradicts it.

For instance, if you suspect your boss is unhappy with you, you might only notice their frown (confirming your belief) and forget that they praised your work yesterday.

Anchoring Bias

Our first impression acts as an anchor for later thoughts. The first piece of information we get has an outsized influence on our belief.

Imagine you assume a new acquaintance is unfriendly because they seemed quiet at first; that initial judgment might anchor your ongoing perception, even after they warm up.

Availability Heuristic

We judge how true or likely something is by how easily it comes to mind. If you can easily recall a dramatic news story about a plane incident, you might believe air travel is more dangerous than it really is—simply because that vivid example is available in your memory.

In reality, calmer, more common facts (like safe flights) don’t stick in our heads as much.

Example

A relatable example: one person shared that they misread a friend’s brief “OK” text and immediately assumed the friend was upset with them.

In reality, the friend was just busy, but that snap judgment (anchored in fear) caused unnecessary stress.

During anxiety, we also tend to jump to worst-case scenarios without proof (“They’re late—something terrible must have happened”).

Our biased thinking convinces us these knee-jerk interpretations are true. Recognizing these mental habits is the first step to not letting them run the show.

Emotional Reasoning: When Feelings Become “Facts”

Emotional reasoning happens when we treat feelings as proof that something is true, even without supporting evidence.

Anxiety makes this especially likely—for example, “I feel unsafe, so I must be in danger,” or “I feel rejected, so they must dislike me.”

Psychologist Julie Smith explains that intense emotions can convince us they reflect reality: “I feel it, therefore it must be a fact.”

Emotions are valid signals about what we care about or fear, but strong feelings—especially in an anxious mind—can cloud judgment.

Social and Cultural Influences on Belief

Beliefs are shaped by the people and culture around us. Humans crave belonging, so we often adopt the views of our social group—sometimes without realizing it.

Group identity and peer pressure can make false beliefs feel safe, especially when “everyone” seems to agree.

Social media intensifies this through echo chambers, where algorithms show us content similar to what we’ve already liked. Over time, we hear the same perspective repeated, and misinformation can spread quickly, especially if it’s emotional or sensational.

For someone with anxiety about acceptance, group agreement can feel more important than evidence.

Why Facts Alone Often Don’t Change Minds

Facts don’t always break false beliefs—especially when those beliefs feel tied to our identity or emotions. Through motivated reasoning, we interpret information in ways that protect our self-image, letting in agreeable facts and deflecting those that challenge us. Accepting certain truths can feel like admitting we’re “bad” or wrong, so our minds resist.

The backfire effect makes it trickier. Research has found that directly debunking a myth can sometimes reinforce the myth instead of dispelling it.

This is mostly because hearing a false statement repeatedly (even in the context of “this isn’t true”) makes it feel familiar, and our brains often mistake familiarity for truth.

When False Beliefs Become Harmful

Some mistaken beliefs cause more than minor misunderstandings—they can create real distress or disrupt daily life.

A false belief can fuel an anxiety spiral, where distorted thoughts trigger anxious feelings, which then reinforce even more distorted thoughts.

For example, believing “I can’t do anything right” may lead you to avoid challenges, preventing you from ever disproving the belief.

False beliefs also strain relationships. Assumptions like “If my partner is quiet, they’re angry” can spark unnecessary conflict or withdrawal. Cognitive distortions such as catastrophizing or mind-reading often work this way, damaging trust and connection.

Avoidance is another consequence. If you think “I’ll embarrass myself if I speak up,” you may miss opportunities to challenge that fear.

In some cases, strong false beliefs are linked to conditions like illness anxiety disorder or psychosis.

How to Gently Challenge a Belief

Challenging a belief doesn’t mean harshly telling yourself “that’s stupid” or simply trying to eliminate the thought. In fact, the gentler and more curious you are with your beliefs, the more effectively you can shift them.

Here are some supportive strategies to test out a belief when you suspect it might not be true:

Slow down and gather evidence

Treat yourself like a friendly investigator. Ask, “What’s the evidence for this belief, and what’s the evidence against it?”

Write it down if you can. Seeing facts in black-and-white can be grounding. Often, you’ll find you have lots of feelings about the belief but not much solid evidence for it.

For example, if you think “Nobody likes me,” list times people have shown warmth toward you as evidence against that thought.

Consider alternative explanations

Our first interpretation is not always the only one. Challenge yourself to come up with 2–3 other ways to view the situation.

If a friend cancels plans, instead of “They secretly dislike me,” alternatives could be “Maybe they were overwhelmed with work or not feeling well.”

This doesn’t deny your concern; it just reminds you that reality might not be as dire as your worry suggests.

Use grounding or mindfulness techniques

Strong emotions can hijack our thinking, so it helps to calm your nervous system before re-examining a belief.

Try a few deep breaths or a quick grounding exercise (for example, name five things you can see around you) to get out of the swirl of thoughts.

When you’re a bit more centered, return to the question and see if the belief still holds the same power. Often, a calmer mind can spot flaws in an anxious thought more easily.

Talk it out with someone you trust

Sometimes verbalizing a belief helps you hear it from an outside perspective. A therapist, counselor, or trusted friend can gently question your assumptions in a way you might not do yourself.

They might ask, “What makes you say that?” or “Do you think everyone who texts late is upset with you, or could it be something else?” The goal isn’t to feel judged; it’s to have an ally in reality-checking.

A professional, in particular, can guide you through techniques (like cognitive-behavioral thought challenging or mindfulness practices) tailored to unrooting unhelpful beliefs.

Remember, the aim is not to invalidate everything you feel, but to separate genuine signals from potentially misleading ones. Think of it as holding your beliefs up to the light to see if they’re solid. By slowing down and using these strategies, you give yourself a chance to update a false belief into a more accurate one. It’s a skill, and with practice, it gets easier to ask: “Is this really true, or is it my anxiety/anger/sadness talking?”

When to Seek Professional Support

If a false or distressing belief dominates your life, professional help can make a difference. Here are signs it may be time to reach out:

- The belief causes significant distress: Persistent thoughts like “I’m in danger” or “I’m unlovable” trigger anxiety, panic, or hopelessness despite reassurance.

- It interferes with daily life: The belief disrupts sleep, concentration, work, relationships, or leads to avoidance (e.g., not driving due to fear).

- You can’t break the cycle on your own: Some beliefs stem from trauma or patterns like transference or limerence, making them hard to shift without support.

Therapists can help identify root causes and use approaches such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or trauma-focused methods. Seeking help is an act of self-care, not failure.

If your beliefs cause ongoing distress or isolation, you don’t have to face them alone—professional guidance can help you move forward.

References

De Coninck, D., Frissen, T., Matthijs, K., Lits, G., Carignan, M., David, M. D., Salerno, S., & Généreux, M. (2021). Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation About COVID-19: Comparative Perspectives on the Role of Anxiety, Depression and Exposure to and Trust in Information Sources. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 646394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394

Lynn, S. J., Evans, J., Laurence, R., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2015). What Do People Believe About Memory? Implications for the Science and Pseudoscience of Clinical Practice. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 60(12), 541. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506001204