Bloom’s Taxonomy is a widely recognized hierarchical framework used by educators to classify and structure educational objectives according to their complexity and specificity.

This taxonomy encompasses three primary domains: cognitive (intellectual processes), affective (emotional responses and attitudes), and psychomotor (physical skills and abilities).

Key Takeaways

- Bloom’s Taxonomy assists educators in defining clear and measurable learning objectives, designing instructional strategies, and creating effective assessments.

- The original 1956 taxonomy focused solely on a cognitive model of learning that can be applied in the classroom, an affective model of learning was published in 1964 and a psychomotor model in the 1970s.

- Critics argue that Bloom’s Taxonomy oversimplifies cognitive complexity and suggests a rigid, linear progression.

- Contemporary educators recommend flexible application of Bloom’s, recognizing that learning often integrates multiple cognitive levels simultaneously rather than sequentially.

Bloom’s Taxonomy systematically organizes learning objectives within three distinct domains, each progressing from simpler to more complex skills:

-

Cognitive Domain (mental skills and intellectual development)

-

Affective Domain (emotional attitudes, values, and appreciation)

-

Psychomotor Domain (physical coordination and motor skills)

Educators employ this taxonomy to clarify learning goals, structure course content, and align assessments effectively.

Historical Development

Benjamin Bloom and his research team developed this taxonomy to provide clarity and structure to educational goals, aiming to facilitate more individualized and effective teaching strategies.

Bloom’s work significantly influenced the concept of Mastery Learning, which promotes personalized feedback and clearly defined learning outcomes to enhance student achievement.

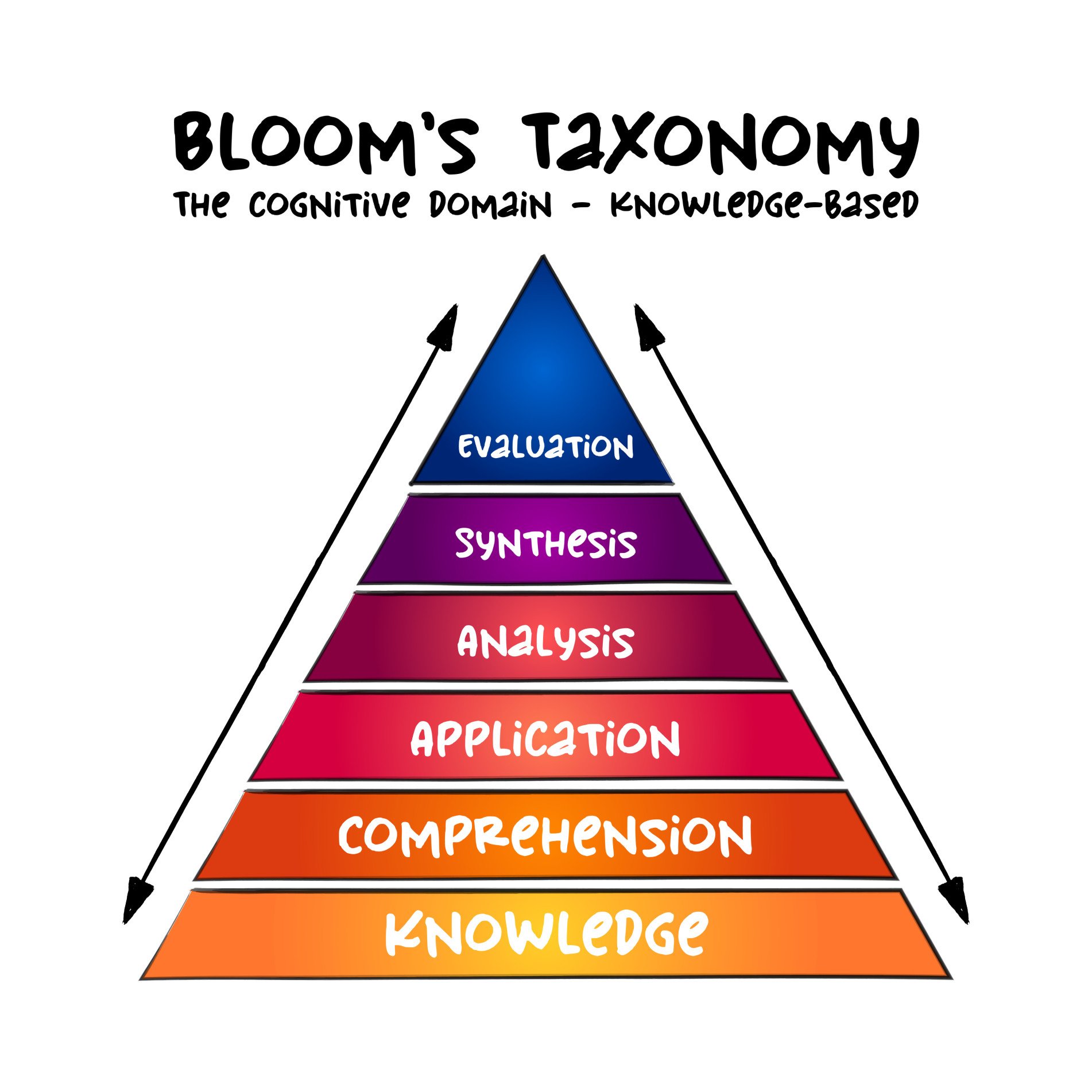

Original Cognitive Domain (1956)

The cognitive domain encompasses intellectual skills, focusing on knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

It describes how we process and use information, from simple recall to complex problem-solving

Bloom’s original taxonomy exclusively focused on cognitive development and was organized as follows:

-

Knowledge: Recalling information and basic facts (e.g., historical dates, mathematical symbols, scientific terms).

-

Comprehension: Understanding concepts and interpreting meaning (e.g., summarizing theories).

-

Application: Utilizing learned information in practical contexts (e.g., solving mathematical problems, conducting lab experiments).

-

Analysis: Breaking down information into parts to examine relationships (e.g., comparing literature themes).

-

Synthesis: Combining knowledge to form new ideas or solutions (e.g., developing original hypotheses).

-

Evaluation: Judging information based on criteria and standards (e.g., critiquing research methodologies).

The Revised Cognitive Taxonomy (2001)

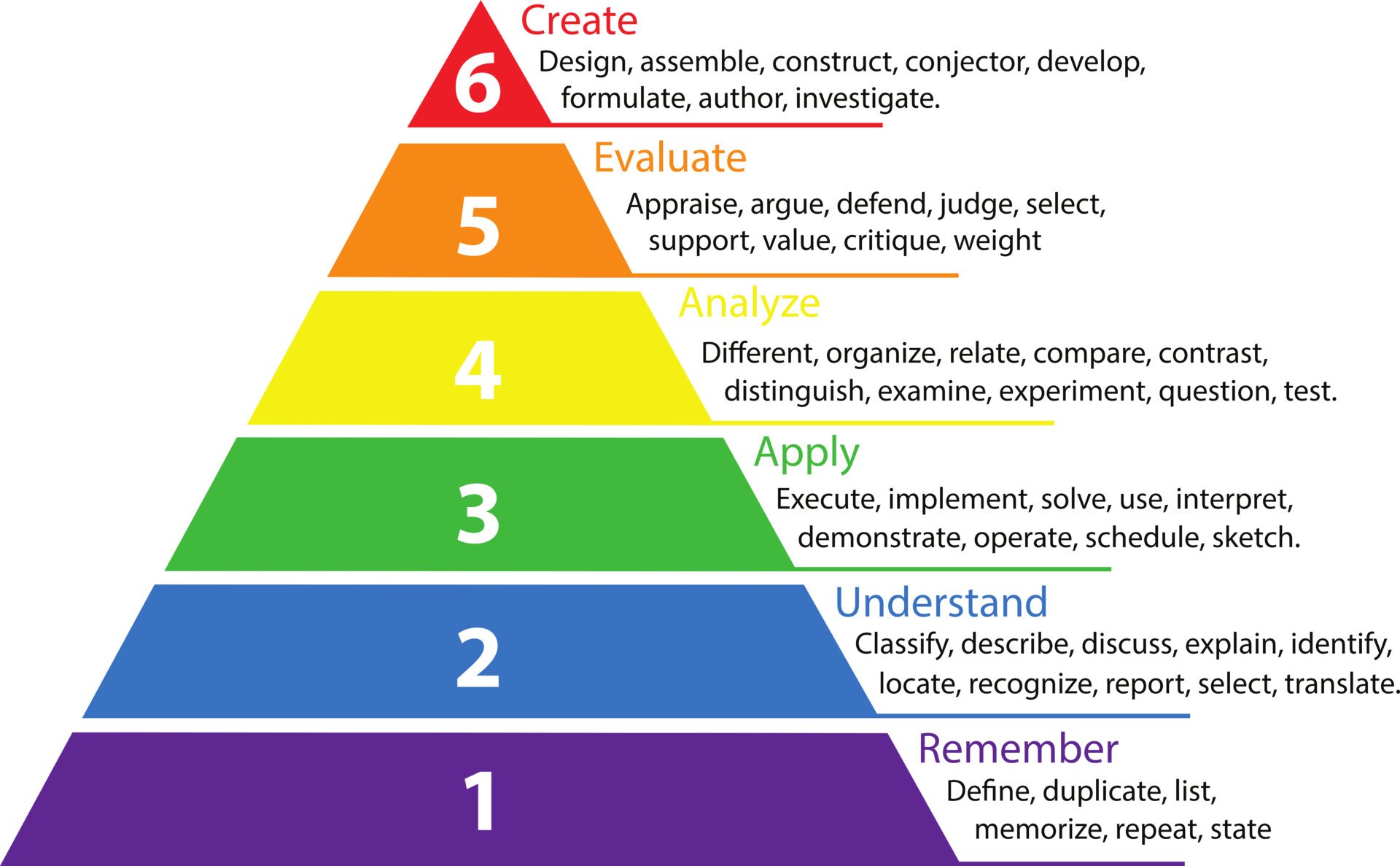

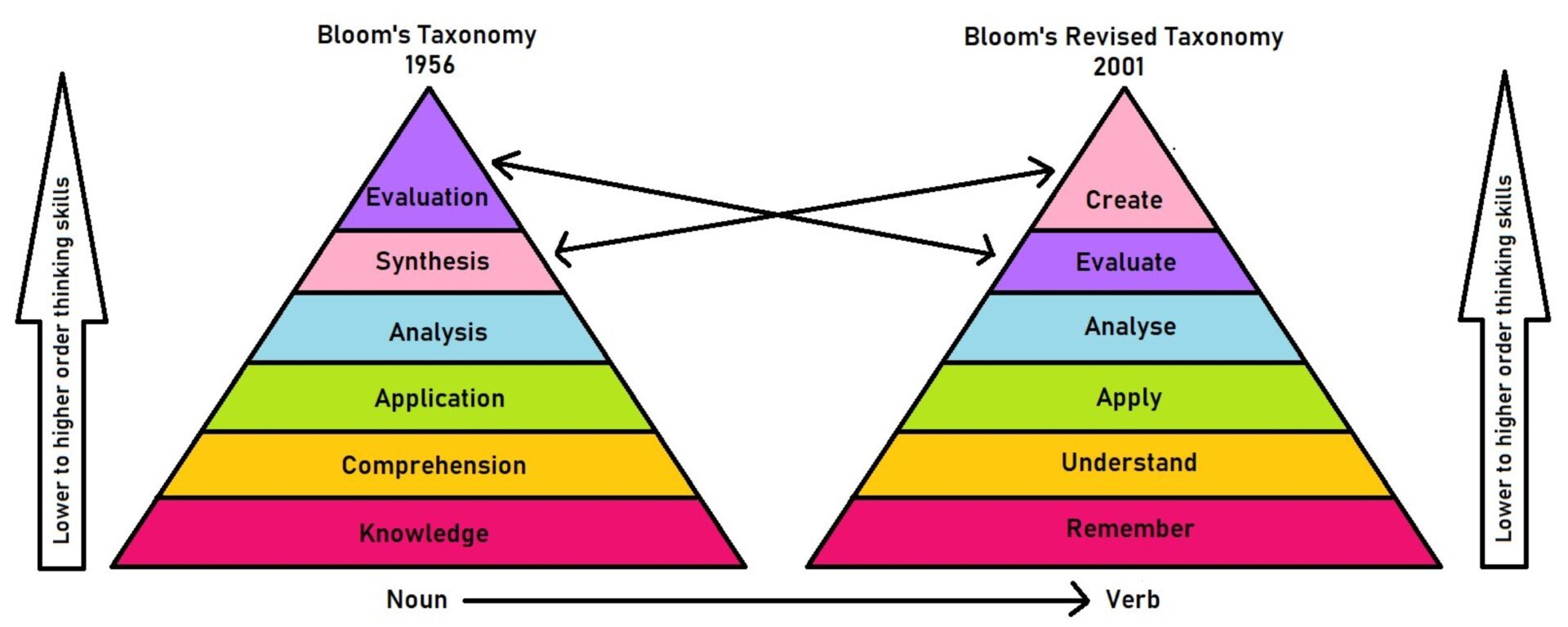

The 2001 revision by Krathwohl and Anderson shifted Bloom’s original cognitive categories from passive nouns to active verbs, emphasizing learner engagement and active participation.

This revised taxonomy emphasizes a more dynamic approach to education instead of shoehorning educational objectives into fixed, unchanging spaces.

1. Remembering: Recalling facts and basic concepts

-

Action verbs: list, define, identify, recall, name, state, describe

-

Example: Naming chemical elements on the periodic table.

2. Understanding: Explaining ideas and concepts

-

Action verbs: explain, summarize, interpret, paraphrase, illustrate, classify

-

Example: Summarizing the main ideas of a historical text.

3. Applying: Using information practically in new situations

-

Action verbs: apply, use, demonstrate, implement, execute, solve

-

Example: Solving math problems using learned formulas.

4. Analyzing: Breaking information into components to explore relationships

-

Action verbs: analyze, compare, contrast, examine, differentiate, categorize

-

Example: Comparing themes in different literary texts.

5. Evaluating: Judging the value of information or ideas based on criteria

-

Action verbs: evaluate, assess, critique, justify, argue, defend, rate

-

Example: Critically assessing the validity of a research study.

6. Creating: Producing new or original work

-

Action verbs: create, design, invent, develop, construct, compose, propose

-

Example: Designing an original science experiment.

Importance of Higher-Order Thinking

Fostering higher-order thinking skills (Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating) is crucial in modern education. These skills help learners:

-

Apply knowledge creatively and critically in novel situations.

-

Move beyond rote memorization to deep, meaningful understanding.

-

Become independent, adaptive learners capable of problem-solving and innovation.

Higher-order thinking is essential in the 21st century, preparing students to face complex challenges, think critically, and continuously innovate in rapidly changing environments.

Differences Between Original and Revised Taxonomy

-

The original taxonomy (1956) used nouns (Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation).

-

The revised taxonomy (2001) emphasizes active verbs (Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, Creating) to reflect dynamic cognitive processes more accurately.

-

The revised version notably elevates “Creating” as the highest form of cognitive activity, emphasizing innovation and creativity as central educational goals.

Knowledge Dimension

Bloom’s revised taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) introduces the Knowledge Dimension, which complements the cognitive domain by clarifying what learners are expected to know.

While the cognitive domain describes how learners use and process knowledge, the Knowledge Dimension classifies the type of knowledge students engage with:

- Factual Knowledge: Knowledge of basic elements, terminology, and details essential to a discipline (e.g. historical dates, mathematical symbols, scientific terms)

- Conceptual Knowledge: Understanding relationships among concepts, principles, and theories (e.g. grasping the principles behind economic theories like supply and demand).

- Procedural Knowledge: Knowing how to perform tasks and processes (e.g. conducting laboratory experiments or following a mathematical algorithm).

- Metacognitive Knowledge: Awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes (e.g. reflecting on study habits to improve personal learning strategies).

By considering all four types of knowledge, teachers can ensure that students develop a well-rounded understanding of the subject matter.

They can move beyond simply memorizing facts to developing deep conceptual understanding and the ability to apply knowledge in practical situations.

Understanding metacognitive knowledge helps teachers guide students in developing self-awareness of their own learning processes.

This is essential for fostering higher-order thinking skills and promoting lifelong learning.

Action Verbs for Each Level

Thanks to Bloom’s Taxonomy, teachers nationwide have a tool to guide the development of assignments, assessments, and overall curricula.

This model helps teachers identify the key learning objectives they want a student to achieve for each unit because it succinctly details the learning process.

The taxonomy explains that (Shabatura, 2013):

- Before you can understand a concept, you need to remember it;

- To apply a concept, you need first to understand it;

- To evaluate a process, you need first to analyze it;

- To create something new, you need to have completed a thorough evaluation

This hierarchy takes students through a process of synthesizing information that allows them to think critically.

Students start with a piece of information and are motivated to ask questions and seek out answers.

Not only does Bloom’s Taxonomy help teachers understand the process of learning, but it also provides more concrete guidance on how to create effective learning objectives.

| Bloom’s Level | Key Verbs (keywords) | Example Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Create | design, formulate, build, invent, create, compose, generate, derive, modify, develop. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to design an original homework problem dealing with the principle of conservation of energy. |

| Evaluate | choose, support, relate, determine, defend, judge, grade, compare, contrast, argue, justify, support, convince, select, evaluate. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to determine whether using conservation of energy or conservation of momentum would be more appropriate for solving a dynamics problem. |

| Analyze | classify, break down, categorize, analyze, diagram, illustrate, criticize, simplify, associate. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to differentiate between potential and kinetic energy. |

| Apply | calculate, predict, apply, solve, illustrate, use, demonstrate, determine, model, perform, present. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to calculate the kinetic energy of a projectile. |

| Understand | describe, explain, paraphrase, restate, give original examples of, summarize, contrast, interpret, discuss. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to describe Newton’s three laws of motion in her/his own words |

| Remember | list, recite, outline, define, name, match, quote, recall, identify, label, recognize. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to recite Newton’s three laws of motion. |

The revised version reminds teachers that learning is an active process, stressing the importance of including measurable verbs in the objectives.

And the clear structure of the taxonomy itself emphasizes the importance of keeping learning objectives clear and concise as opposed to vague and abstract (Shabatura, 2013).

Bloom’s Taxonomy even applies at the broader course level. That is, in addition to being applied to specific classroom units, Bloom’s Taxonomy can be applied to an entire course to determine the learning goals of that course.

Specifically, lower-level introductory courses, typically geared towards freshmen, will target Bloom’s lower-order skills as students build foundational knowledge.

However, that is not to say that this is the only level incorporated, but you might only move a couple of rungs up the ladder into the applying and analyzing stages.

On the other hand, upper-level classes don’t emphasize remembering and understanding, as students in these courses have already mastered these skills.

As a result, these courses focus instead on higher-order learning objectives such as evaluating and creating (Shabatura, 2013).

In this way, professors can reflect upon what type of course they are teaching and refer to Bloom’s Taxonomy to determine what they want the overall learning objectives of the course to be.

Having these clear and organized objectives allows teachers to plan and deliver appropriate instruction, design valid tasks and assessments, and ensure that such instruction and assessment actually aligns with the outlined objectives (Armstrong, 2010).

Overall, Bloom’s Taxonomy helps teachers teach and students learn!

The Affective Domain (1964)

The affective domain describes how we deal with emotions, feelings, and values.

It covers attitudes, appreciation, and motivation, ranging from simple awareness to complex character development. It focuses on the emotional growth of a learner.

From lowest to highest, with examples included, the five levels are:

-

Receiving: Awareness and willingness to hear new ideas (e.g., students will demonstrate attentiveness by actively listening during peer presentations.).

-

Responding: Active participation and engagement (e.g., students will actively participate in group discussions, contributing thoughtful feedback to classmates).

-

Valuing: Internalizing values and recognizing their significance (e.g., students will express appreciation and respect for diverse perspectives during class debates).

-

Organizing: Integrating new values within one’s existing value system (e.g., students will integrate principles of ethical decision-making into their personal value system, demonstrated by reflecting on moral dilemmas in writing assignments.).

-

Characterizing: Consistently embodying internalized values in everyday behavior (e.g., students will consistently demonstrate integrity and responsibility in collaborative projects, exemplifying professional ethics and behaviors.).

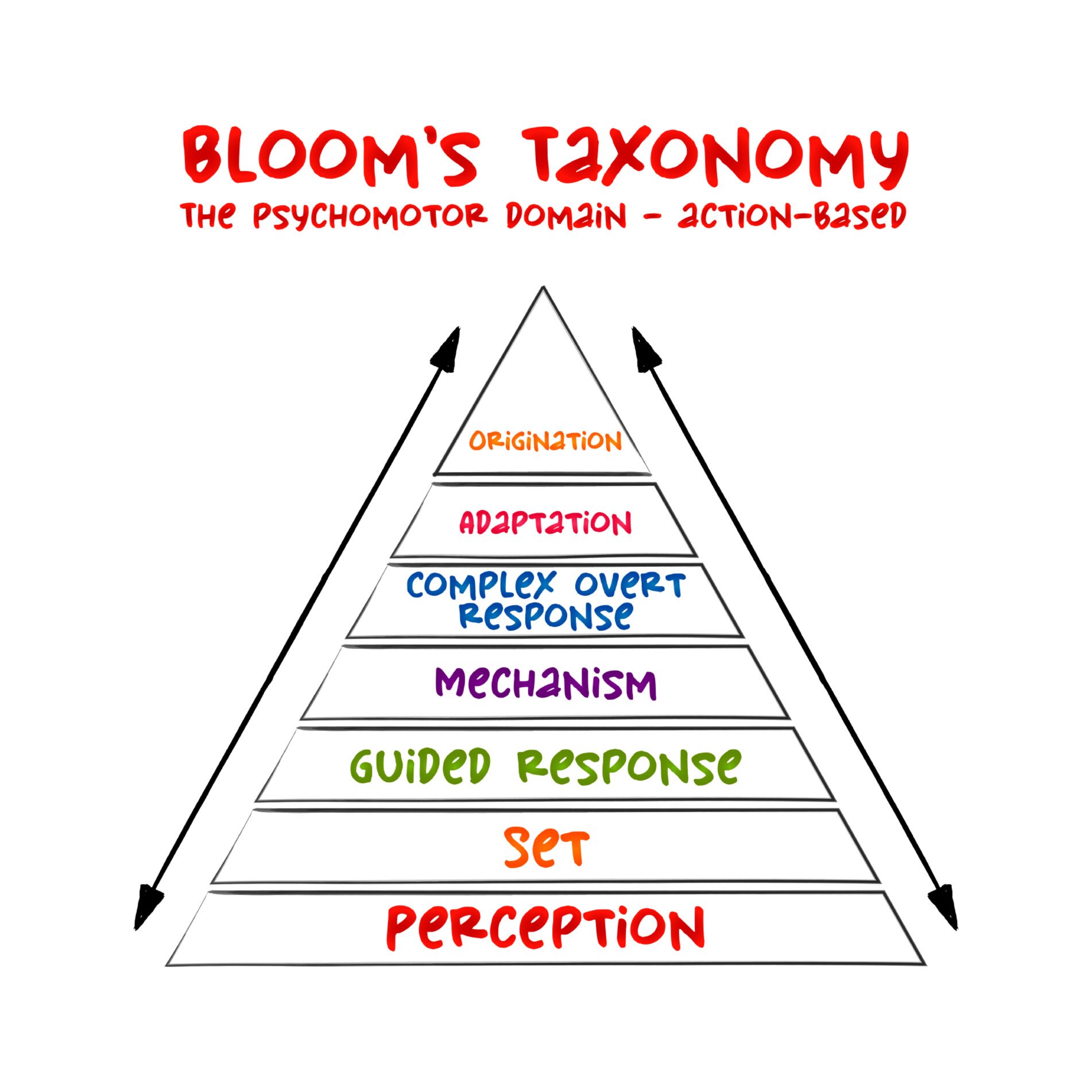

The Psychomotor Domain (1972)

The psychomotor domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy refers to the ability to physically manipulate tools or instruments.

It focuses on the development of physical skills, coordination, and movement abilities, from basic reflexes to complex actions.

This domain emphasizes the development of physical dexterity and motor abilities, including physical movement, coordination, and use of motor-skill areas.

Mastery of these specific skills is marked by speed, precision, and distance.

Psychomotor skills range from simple tasks, such as washing a car, to more complex tasks, like operating intricate technological equipment.

The domain involves learning through progressive stages of movement, ultimately leading to the mastery of physical and manual tasks.

-

Perception: Using sensory cues to guide motor activity (e.g., catching a ball based on visual cues).

-

Set: Readiness and willingness to perform (e.g., showing interest in learning new sports).

-

Guided Response: Initial stages of learning through imitation and trial-and-error (e.g., practicing basic dance movements).

-

Mechanism: Developing habitual movements and skills performed with confidence (e.g., executing routine gymnastics skills).

-

Complex Overt Response: Skilled, efficient, and automatic execution of complex tasks (e.g., consistently performing precise athletic techniques).

-

Adaptation: Adjusting motor skills effectively in response to different conditions (e.g., modifying dance routines to match new music).

-

Origination: Creating novel and original motor skills (e.g., inventing a unique style of artistic performance).

Critical Evaluation

Bloom’s Taxonomy accomplishes the seemingly daunting task of taking the important and complex topic of thinking and giving it a concrete structure.

The taxonomy continues to provide teachers and educators with a framework for guiding the way they set learning goals for students and how they design their curriculum.

And by having specific questions or general assignments that align with Bloom’s principles, students are encouraged to engage in higher-order thinking.

However, even though it is still used today, this taxonomy does not come without its flaws. As mentioned before, the initial 1956 taxonomy presented learning as a static concept.

Although this was ultimately addressed by the 2001 revised version that included active verbs to emphasize the dynamic nature of learning, Bloom’s updated structure is still met with multiple criticisms.

Many psychologists take issue with the pyramid nature of the taxonomy. The shape creates the false impression that these cognitive steps are discrete and must be performed independently of one another (Anderson & Krathwol, 2001).

However, most tasks require several cognitive skills to work in tandem with each other. In other words, a task will not be only an analysis or a comprehension task. Rather, they occur simultaneously as opposed to sequentially.

The structure also makes it seem like some of these skills are more difficult and important than others. However, adopting this mindset causes less emphasis on knowledge and comprehension, which are as, if not more important, than the processes towards the top of the pyramid.

Additionally, author Doug Lemov (2017) argues that this contributes to a national trend devaluing knowledge’s importance. He goes even further to say that lower-income students who have less exposure to sources of information suffer from a knowledge gap in schools.

A third problem with the taxonomy is that the sheer order of elements is inaccurate. When we learn, we don’t always start with remembering and then move on to comprehension and creating something new. Instead, we mostly learn by applying and creating.

For example, you don’t know how to write an essay until you do it. And you might not know how to speak Spanish until you actually do it (Berger, 2020).

The act of doing is where the learning lies, as opposed to moving through a regimented, linear process. Despite these several valid criticisms of Bloom’s taxonomy, this model is still widely used today.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Armstrong, R. J. (1970). Developing and Writing Behavioral Objectives.

Berger, R. (2020). Here’s what’s wrong with bloom’s taxonomy: A deeper learning perspective (opinion). Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-heres-whats-wrong-with-blooms-taxonomy-a-deeper-learning-perspective/2018/03

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20, 24.

Bloom, B. S. (1971). Mastery learning. In J. H. Block (Ed.), Mastery learning: Theory and practice (pp. 47–63). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Clark, D. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy: The affective domain. Retrieved from http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/affective_domain.html

Guskey, T. R. (2005). Formative Classroom Assessment and Benjamin S. Bloom: Theory, Research, and Implications. Online Submission.

Harrow, A.J. (1972). A taxonomy of the psychomotor domain. New York: David McKay Co.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice, 41 (4), 212-218.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., & Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook II: Affective domain. New York: David McKay Co.

Lemov, D. (2017). Bloom’s taxonomy-that pyramid is a problem. Retrieved from https://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/blooms-taxonomy-pyramid-problem/

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.celt.iastate.edu/teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy/

Shabatura, J. (2013). Using bloom’s taxonomy to write effective learning objectives. Retrieved from https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/

Simpson, E. J. (1972). The classification of educational objectives in the Psychomotor domain, Illinois University. Urbana.