Key Takeaways

- Reliability in research refers to the consistency and reproducibility of measurements. It assesses the degree to which a measurement tool produces stable and dependable results when used repeatedly under the same conditions.

- Validity in research refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of measurements. It examines whether a research instrument or method effectively measures what it claims to measure.

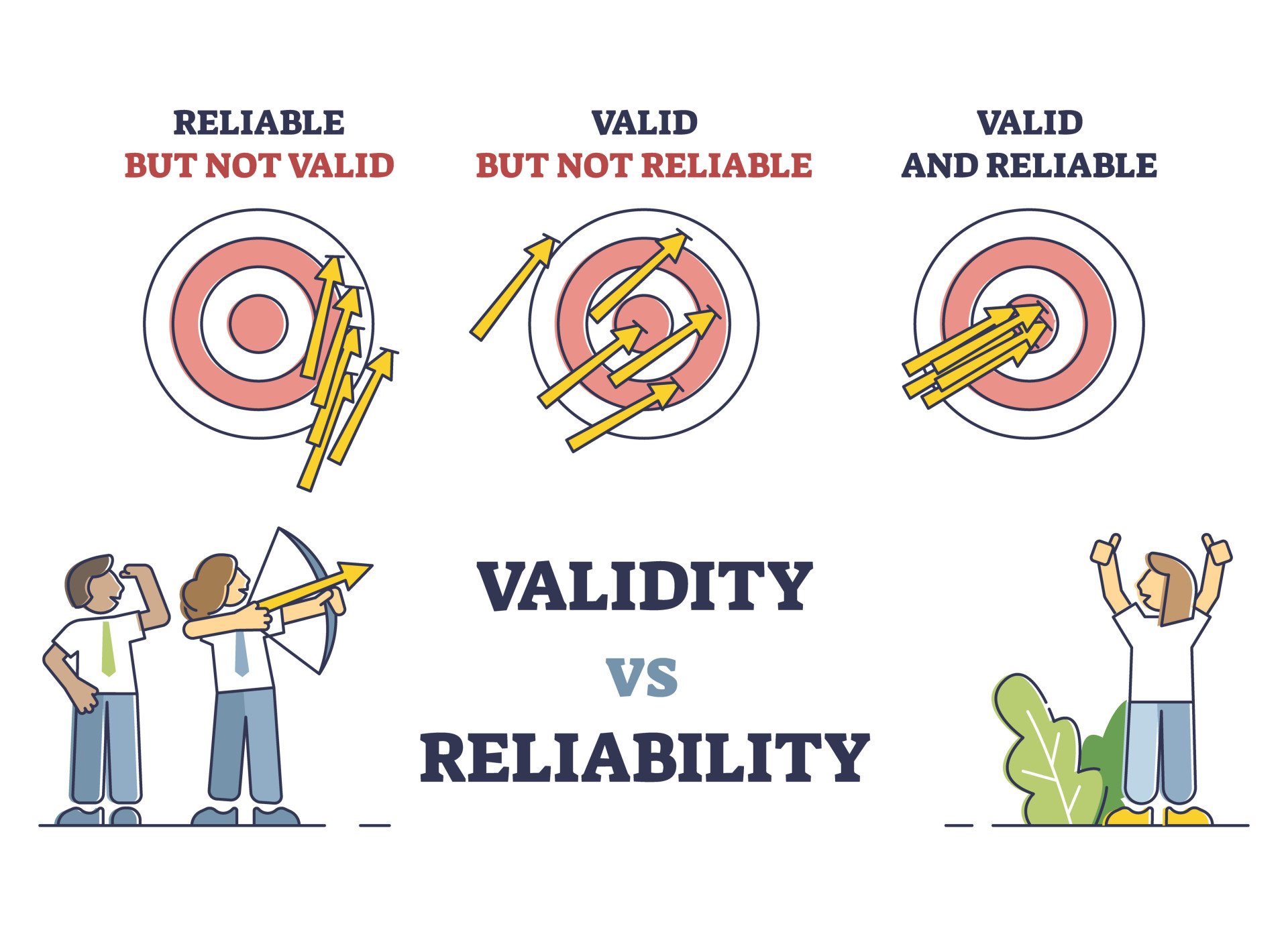

- A reliable instrument may not necessarily be valid, as it might consistently measure something other than the intended concept.

| Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

| What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

| How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

| How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be reproducible, but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be reproducible. |

While reliability is a prerequisite for validity, it does not guarantee it.

A reliable measure might consistently produce the same result, but that result may not accurately reflect the true value.

For instance, a thermometer could consistently give the same temperature reading, but if it is not calibrated correctly, the measurement would be reliable but not valid.

Assessing Validity

A valid measurement accurately reflects the underlying concept being studied.

For example, a valid intelligence test would accurately assess an individual’s cognitive abilities, while a valid measure of depression would accurately reflect the severity of a person’s depressive symptoms.

Quantitative validity can be assessed through various forms, such as content validity (expert review), criterion validity (comparison with a gold standard), and construct validity (measuring the underlying theoretical construct).

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the extent to which a psychological instrument accurately and fully reflects all the features of the concept being measured.

Content validity is a fundamental consideration in psychometrics, ensuring that a test measures what it purports to measure.

Content validity is not merely about a test appearing valid on the surface, which is face validity. Instead, it goes deeper, requiring a systematic and rigorous evaluation of the test content by subject matter experts.

For instance, if a company uses a personality test to screen job applicants, the test must have strong content validity, meaning the test items effectively measure the personality traits relevant to job performance.

Content validity is often assessed through expert review, where subject matter experts evaluate the relevance and completeness of the test items.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity examines how well a measurement tool corresponds to other valid measures of the same concept.

It includes concurrent validity (existing criteria) and predictive validity (future outcomes).

For example, when measuring depression with a self-report inventory, a researcher can establish criterion validity if scores on the measure correlate with external indicators of depression such as clinician ratings, number of missed work days, or length of hospital stay.

Criterion validity is important because, without it, tests would not be able to accurately measure in a way consistent with other validated instruments.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a particular measurement reflects the theoretical construct (existing theory and knowledge) it is intended to measure.

It goes beyond simply assessing whether a test covers the right material or predicts specific outcomes.

Instead, construct validity focuses on the meaning of the test scores and how they relate to the theoretical framework of the construct.

For instance, if a researcher develops a new questionnaire to evaluate aggression, the instrument’s construct validity would be the extent to which it assesses aggression as opposed to assertiveness, social dominance, and so on.

Assessing construct validity involves multiple methods and often relies on the accumulation of evidence over time.

Assessing Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of measurement results.

In simpler terms, a reliable tool produces consistent results when applied repeatedly under the same conditions.

Test-Retest Reliability

This method assesses the stability of a measure over time.

The same test is administered to the same group twice, with a reasonable time interval between tests.

The correlation coefficient between the two sets of scores represents the reliability coefficient.

A high correlation indicates that individuals maintain their relative positions within the group despite potential overall shifts in performance.

For example, a researcher administers a depression screening test to 100 participants. Two weeks later, they give the exact same test to the same people.

Comparing scores between Time 1 and Time 2 reveals a correlation of 0.85, indicating good test-retest reliability since the scores remained stable over time.

Factors influencing test-retest reliability:

- Memory effects: If respondents remember their answers from the first testing, it could artificially inflate the reliability coefficient.

- Time interval between testings: A short interval might lead to inflated reliability due to memory effects, while an excessively long interval increases the chance of genuine changes in the trait being measured.

- Test length and nature of test materials: These can also affect the likelihood of respondents remembering their previous answers.

- Stability of the trait being measured: If the trait itself is unstable and subject to change, test-retest reliability might be low even with a reliable measure.

Interrater Reliability

Interrater reliability assesses the consistency or agreement among judgments made by different raters or observers.

Multiple raters independently assess the same set of targets, and the consistency of their judgments is evaluated.

Adequate training equips raters with the necessary knowledge and skills to apply scoring criteria consistently, reducing systematic errors.

A high interrater reliability indicates that the raters are interchangeable and the rating protocol is reliable.

For example:

- Research: Evaluating the consistency of coding in qualitative research or assessing the agreement among raters evaluating behaviors in observational studies.

- Education: Determining the degree of agreement among teachers grading essays or other subjective assignments.

- Clinical Settings: Evaluating the consistency of diagnoses made by different clinicians based on the same patient information.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency refers to the consistency of measurement itself. It examines the degree to which different items within a test or scale are measuring the same underlying construct.

For instance, consider a test designed to assess self-esteem.

If the items within the test are internally consistent, individuals with high self-esteem should generally score highly on all or most of the items. Conversely, those with low self-esteem should consistently score lower on those same items.

While internal consistency is a necessary condition for validity, it does not guarantee it. A measure can be internally consistent but still not accurately measure the intended construct.

Methods for estimating internal consistency:

- Split-half reliability divides a test into two parts (such as odd and even number items) and correlates their scores to check consistency.

- Cronbach’s alpha (α) is the most widely used measure of internal consistency. It represents the average of all possible split-half reliability coefficients that could be computed from the test.

Ensuring Validity

- Define concepts clearly: Start with a clear and precise definition of the concepts you want to measure. This clarity will guide the selection or development of appropriate measurement instruments.

- Use established measures: Whenever possible, use well-established and validated measures that are reliable and valid in previous research. If adapting a measure from a different culture or language, carefully translate and validate it for the target population.

- Pilot test instruments: Before conducting the main study, pilot test your measurement instruments with a smaller sample to identify potential issues with wording, clarity, or response options.

- Use multiple measures (mixed methods): Employing multiple methods of data collection (e.g., interviews, observations, surveys) or data analysis can enhance the validity of the findings by providing converging evidence from different sources.

- Address potential biases: Carefully consider factors that could introduce bias into the research, such as sampling methods, data collection procedures, or the researcher’s own preconceptions.

Ensuring Reliability

- Standardize procedures: Establish clear and consistent procedures for data collection, scoring, and analysis. This standardization helps minimize variability due to procedural inconsistencies.

- Train observers or raters: If using multiple raters, provide thorough training to ensure they understand the rating scales, criteria, and procedures. This training enhances interrater reliability by reducing subjective variations in judgments.

- Optimize measurement conditions: Create a controlled and consistent environment for data collection to minimize external factors that could influence responses. For example, ensure participants have adequate privacy, time, and clear instructions.

- Use reliable instruments: Select or develop measurement instruments that have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability, such as a high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Address potential issues with reverse-coded items or item heterogeneity that can affect internal consistency.

How should I report validity and reliability in my research?

- Introduction: Discuss previous research on the validity and reliability of the chosen measures, highlighting any limitations or considerations.

- Methodology: Detail the steps taken to ensure validity and reliability, including the measures used, sampling methods, data collection procedures, and steps to address potential biases.

- Results: Report the reliability coefficients obtained (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, Cohen’s Kappa) and discuss their implications for the study’s findings.

- Discussion: Critically evaluate the validity and reliability of the findings, acknowledging any limitations or areas for improvement.

validity and reliability in qualitative & quantitative research

While both qualitative and quantitative research strive to produce credible and trustworthy findings, their approaches to ensuring reliability and validity differ.

Qualitative research emphasizes the richness and depth of understanding, and quantitative research focuses on measurement precision and statistical analysis.

Qualitative Research

While traditional quantitative notions of reliability and validity may not always directly apply, qualitative researchers emphasize trustworthiness and transferability.

Credibility refers to the confidence in the truth and accuracy of the findings, often enhanced through prolonged engagement, persistent observation, and triangulation.

Transferability involves providing rich descriptions of the research context to allow readers to determine the applicability of the findings to other settings.

Confirmability is the degree to which the findings are shaped by the participants’ experiences rather than the researcher’s biases, often addressed through reflexivity and audit trails.

They focus on establishing confidence in the findings by:

- Triangulating data from multiple sources.

- Member checking, allowing participants to verify the interpretations.

- Providing thick, rich descriptions to enhance transferability to other contexts.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research typically relies more heavily on statistical measures of reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, test-retest correlations) and validity (e.g., factor analysis, correlations with criterion measures).

The goal is to demonstrate that the measures are consistent, accurate, and meaningfully related to the concepts they are intended to assess.