Safety behaviors—sometimes called safety-seeking behaviors—are actions people take to reduce anxiety in situations they expect will go badly.

They’re not usually harmful on their face, but it’s how and why we use them that matters.

For instance, someone might wear headphones on public transport—not because they’re anxious about speaking to others, but simply to enjoy music.

The key question is: Would you feel anxious if you couldn’t do this? If yes, it’s likely a safety behavior.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you are concerned that you may have an anxiety disorder or another mental health condition, please consult a qualified healthcare provider.

These behaviors can offer a sense of control and relief in the short term—but they’re a double-edged sword.

While they might make a scenario feel more bearable, they also block opportunities to test whether feared outcomes might not happen.

Over time, this prevents us from learning that these situations might be less threatening than we think.

It might be helpful to imagine safety behaviors as emotional crutches.

Examples

Here are some common safety behaviors seen across different types of anxiety:

Social Anxiety

- Avoiding eye contact to reduce perceived judgment

- Rehearsing sentences or “scripts” before speaking

- Using a phone or drink as a prop to avoid interaction

- Sitting at the edge of a group or near the door for quick escape

Panic Disorder

- Carrying water or medication “just in case”

- Staying close to exits or familiar routes

- Avoiding exercise or caffeine to prevent bodily sensations that mimic panic

- Leaning against walls or sitting to feel more stable

Phobias

- Avoiding feared objects or animals but taking precautions (e.g., crossing the street if a dog is nearby)

- Carrying a “safety object” like pepper spray or sanitizer

- Keeping excessive distance from the feared stimulus

- Only facing the phobia with someone else present

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Repeatedly checking locks, appliances, or personal items

- Excessive handwashing or cleaning rituals

- Seeking reassurance from others to confirm safety (“Did I lock the door?”)

- Mentally repeating phrases or prayers to ward off harm

Why Do People Use Safety Behaviors?

Reduce anxiety temporarily

Safety behaviors are used because they offer short-term relief from emotional discomfort.

Engaging in them can make a stressful situation feel more manageable immediately, which is why they’re so tempting in the moment.

For example, disguising anxious feelings by rehearsing what to say can tamp down panic—for now.

Provide a sense of control or escape

People use safety behaviors to gain a sense of control or create a quick escape from perceived threats.

Whether it’s planning ahead, taking small precautions, or using a “safety signal,” the goal is to feel safer in the face of anxiety.

Tied to fear of judgment, harm, or losing control

These behaviors often reflect underlying fears—of being judged, getting hurt, or losing control. People perform safety behaviors to protect themselves from embarrassment or perceived danger, even if those situations may not actually be harmful.

The Link to Avoidance

Safety behaviors are a form of partial avoidance—a middle ground between total avoidance and full exposure.

While avoidance means not confronting the feared situation at all, safety behaviors allow engagement—but with subtle “crutches.”

For example, someone might go to a social event but avoid eye contact or rehearse lines in advance.

Though it may seem less extreme than outright avoidance, these behaviors still block full exposure to the feared scenario.

By using safety behaviors, individuals avoid fully testing their fears. This prevents them from learning that feared outcomes might not materialize, which in turn keeps anxiety entrenched.

How Safety Behaviors Keep Anxiety Going

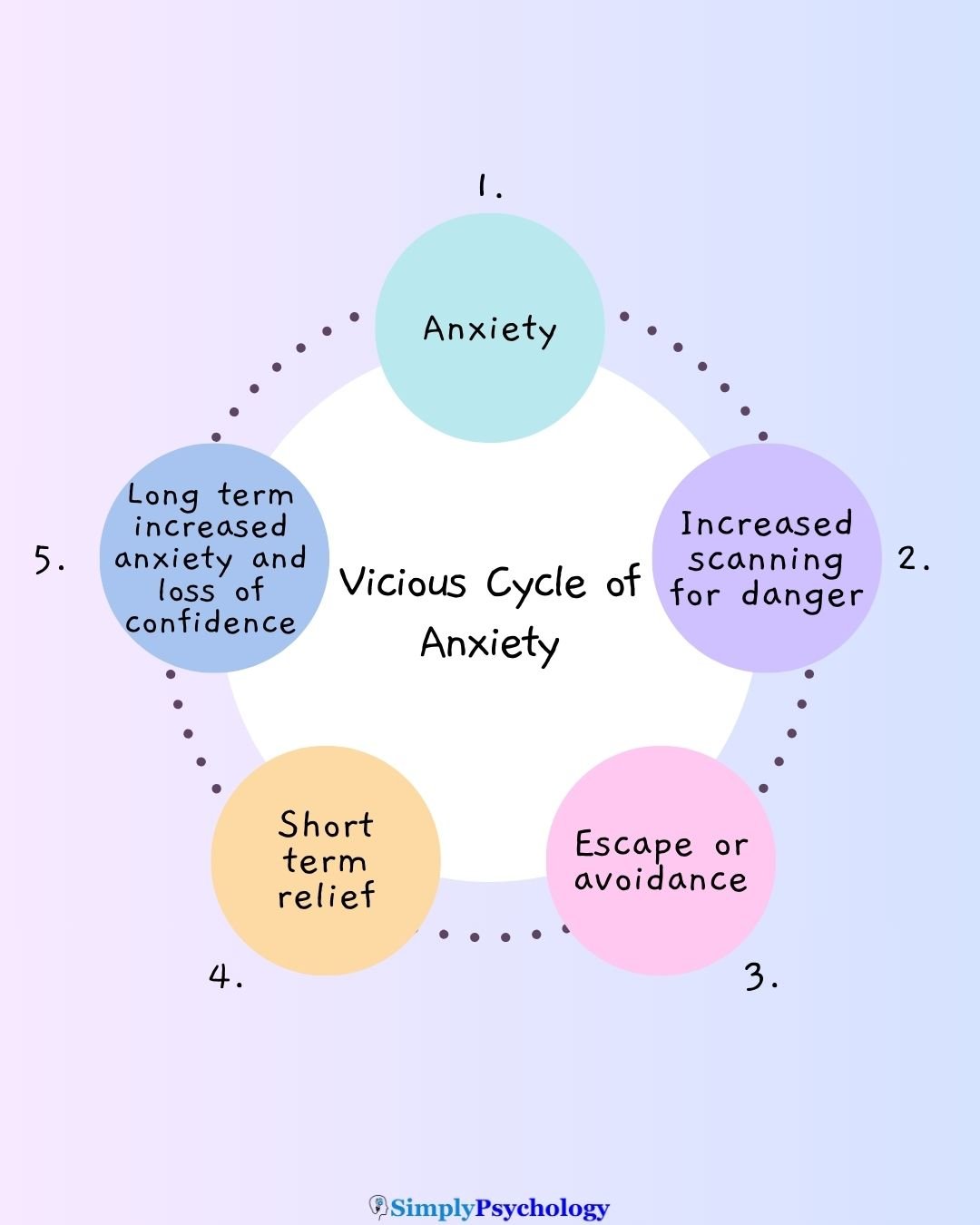

Safety behaviors play a key role in maintaining the anxiety cycle. When someone feels anxious, a safety behavior offers quick relief—but this stops the chance to uncover that the feared outcome may never happen.

In effect, it prevents disconfirmation of anxiety-driven beliefs and reinforces the notion that the world is dangerous—even when it’s not.

Over time, this confirms and cements the belief that the safety behaviors themselves are necessary to stay okay.

In that sense, safety behaviors keep anxiety alive, rather than letting it fade naturally. This pattern is well noted in cognitive-behavioral literatures on anxiety maintenance.

Interference With Therapy

Safety behaviors can undermine the effectiveness of exposure therapy—a core component of CBT for anxiety.

When used during exposure, they draw attention away from the feared experience, reducing chances to learn that the situation may not be harmful—an essential piece of therapeutic progress.

Are Safety Behaviors Always Harmful?

Safety behaviors aren’t inherently harmful—some serve essential, adaptive roles in everyday life. For example, carrying an inhaler if you have asthma is a protective action grounded in real health needs, not anxiety.

The key lies in motivation and context: adaptive behaviors address genuine risks, such as checking water temperature before getting in the bath or looking both ways before crossing the road.

In contrast, anxiety-driven safety behaviors respond to exaggerated or imagined threats and can reinforce fear over time.

Understanding this distinction—and balancing safety with flexibility—is essential in distinguishing when a behavior is helpful versus when it’s maintaining anxiety.

How to Reduce Safety Behaviors

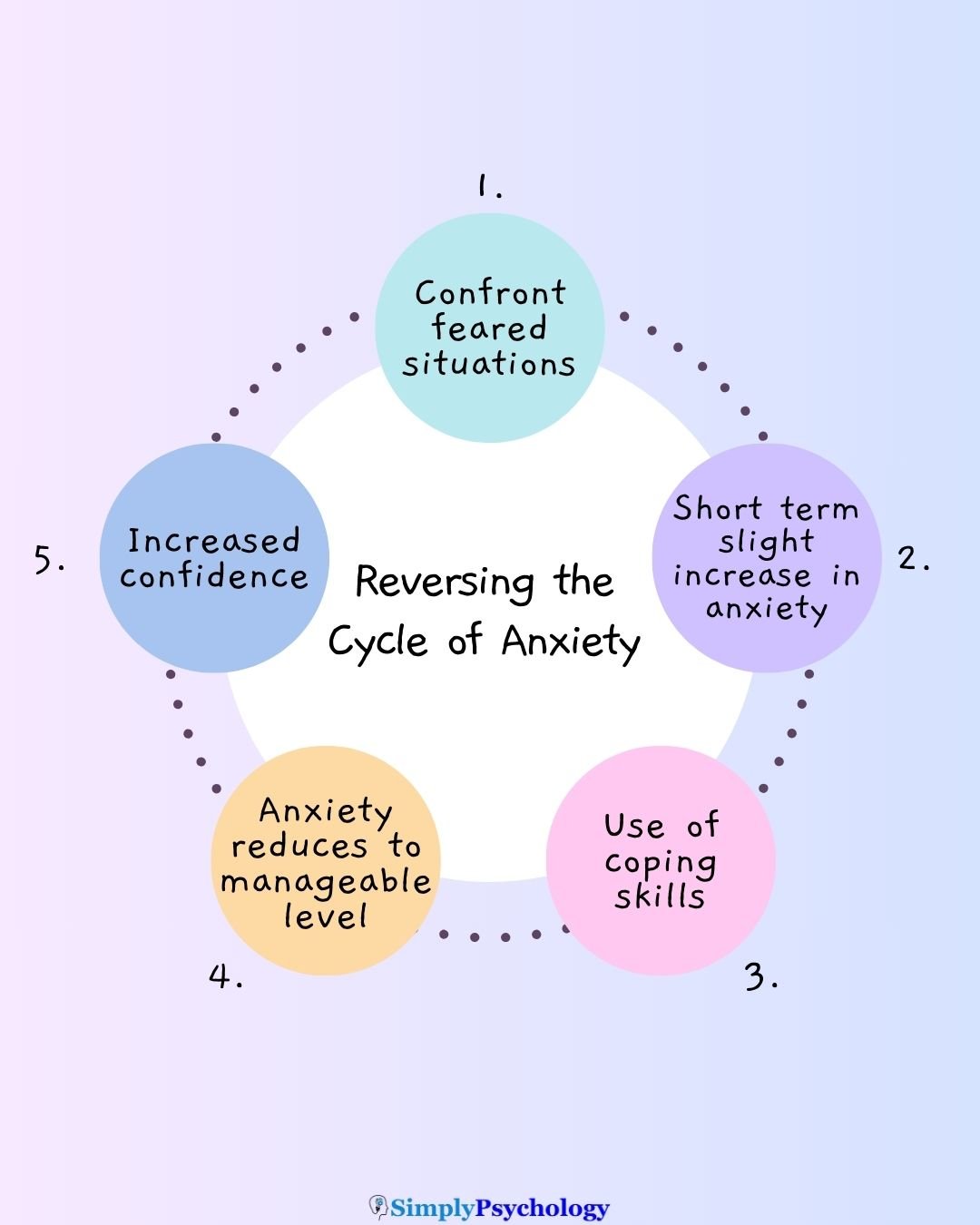

Reducing safety behaviors begins with education—knowing that the goal isn’t to eliminate every protective habit overnight, but to gradually challenge anxiety in manageable ways.

Experts in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) emphasize that identifying and tapering safety behaviors can help build sustainable confidence, rather than reliance on temporary “coping tricks” cbtaaa.com.

From a CBT perspective, the focus is on facing fears without crutches. Exposure therapy plays a key role here: by encouraging repeated, controlled contact with feared stimuli, individuals can form new associations—learning that discomfort doesn’t equate to danger.

However, experts caution against a sudden, all-or-nothing approach. A graded reduction—phasing out safety behaviors step by step—is often more effective. This keeps anxiety manageable and preserves engagement, especially early in the process.

Remember to seek advice from a healthcare professional if you need support with managing your safety behaviors.

Practical Tips for Awareness

- Identify personal safety behaviors: Notice patterns—like always rehearsing lines before social interaction or checking your phone to mask anxiety. Awareness is the first step to change (CBT insight on identifying subtle avoidance)

- Journaling or self-reflection: Keep a small log of moments when anxiety arises and what action you take—this builds insight into habitual safety strategies.

- Track frequency: Over time, note how often you lean on these behaviors. Seeing the patterns helps you choose a starting point for gradual reduction.

These practices help readers observe and understand their own safety behaviors—critical steps toward mindful change.

Working With a Therapist

While this article remains educational, professionals can help tailor strategies—like graded exposure or anxiety hierarchies—to your unique situation, ensuring that reductions in safety behaviors are realistic and supportive.

Collaborating with a therapist can make the process more structured, safe, and personally relevant.

Remember: this article isn’t a therapy guide, but a complement—encouraging readers to seek professional support for personalized care.

Resources

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI) What are safety behaviours?

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI) Stepping out of Social Anxiety

Evans, R., Chiu, K., Clark, D. M., Waite, P., & Leigh, E. (2021). Safety behaviours in social anxiety: An examination across adolescence. Behaviour research and therapy, 144, 103931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103931

Sharpe, L., Todd, J., Scott, A., Gatzounis, R., Menzies, R. E., & Meulders, A. (2022). Safety behaviours or safety precautions? The role of subtle avoidance in anxiety disorders in the context of chronic physical illness. Clinical psychology review, 92, 102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102126