Hypomania is a mood state marked by elevated energy, mood, and activity. It can feel exciting or productive but often signals an underlying mental health condition—typically bipolar II disorder. Though less severe than full-blown mania, hypomania can still affect daily life and relationships.

Understanding hypomania is essential. Its symptoms are often mistaken for enthusiasm or high energy, delaying diagnosis. Recognizing hypomania early can lead to better management and prevent escalation.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice or diagnosis.

Key Takeaways

- Hypomania is a period of elevated or irritable mood and increased energy that lasts at least four days and is often linked to bipolar II disorder.

- Common symptoms include reduced need for sleep, racing thoughts, rapid speech, impulsive behavior, and inflated self-confidence.

- It may feel productive or exciting at first, but it can lead to disrupted relationships, financial issues, and emotional crashes.

- Hypomania differs from mania in that it doesn’t involve psychosis or require hospitalization, but it can still impact daily functioning.

- If mood changes cause problems or follow a pattern, it’s important to seek support from a qualified mental health professional.

What Is Hypomania?

Hypomania is a period of unusually elevated, irritable, or expansive mood with increased activity or energy.

According to the DSM-5, episodes last at least four consecutive days and involve noticeable changes in behavior and functioning.

Unlike mania, hypomania doesn’t include psychosis or require hospitalization. People may function relatively well, but behavior shifts are still clear to others.

It’s commonly linked to bipolar II disorder, which features alternating episodes of depression and hypomania.

While mania often leads to major disruption or psychosis, hypomania tends to be subtler but still disruptive.

For diagnosis, professionals look for patterns in mood history and rule out external causes like substance use or medical conditions [NIMH].

How Hypomania Feels: Common Experiences

People often describe hypomania as a high-energy state where everything feels possible. Thoughts race, sleep becomes unnecessary, and confidence surges.

One forum user noted, “I feel powerful and untouchable… I don’t need food or sleep.”

Many find it pleasant at first. Increased creativity, sociability, and productivity are common.

One person wrote, “It’s like being the most charismatic version of myself.”

But the boost often comes with downsides. Restlessness, irritability, or overconfidence can surface.

A forum user shared, “I start talking fast, get easily annoyed, and think I need to fix everything around me.”

Psychiatrist Dr. James Phelps points out that euphoric hypomania often shifts into irritability if it continues unchecked:

“Patients more commonly go through a phase that is initially pleasurable; but later, perhaps driven by the decreased sleep that accompanies early hypomania, the experience can change into something much more dysphoric.”

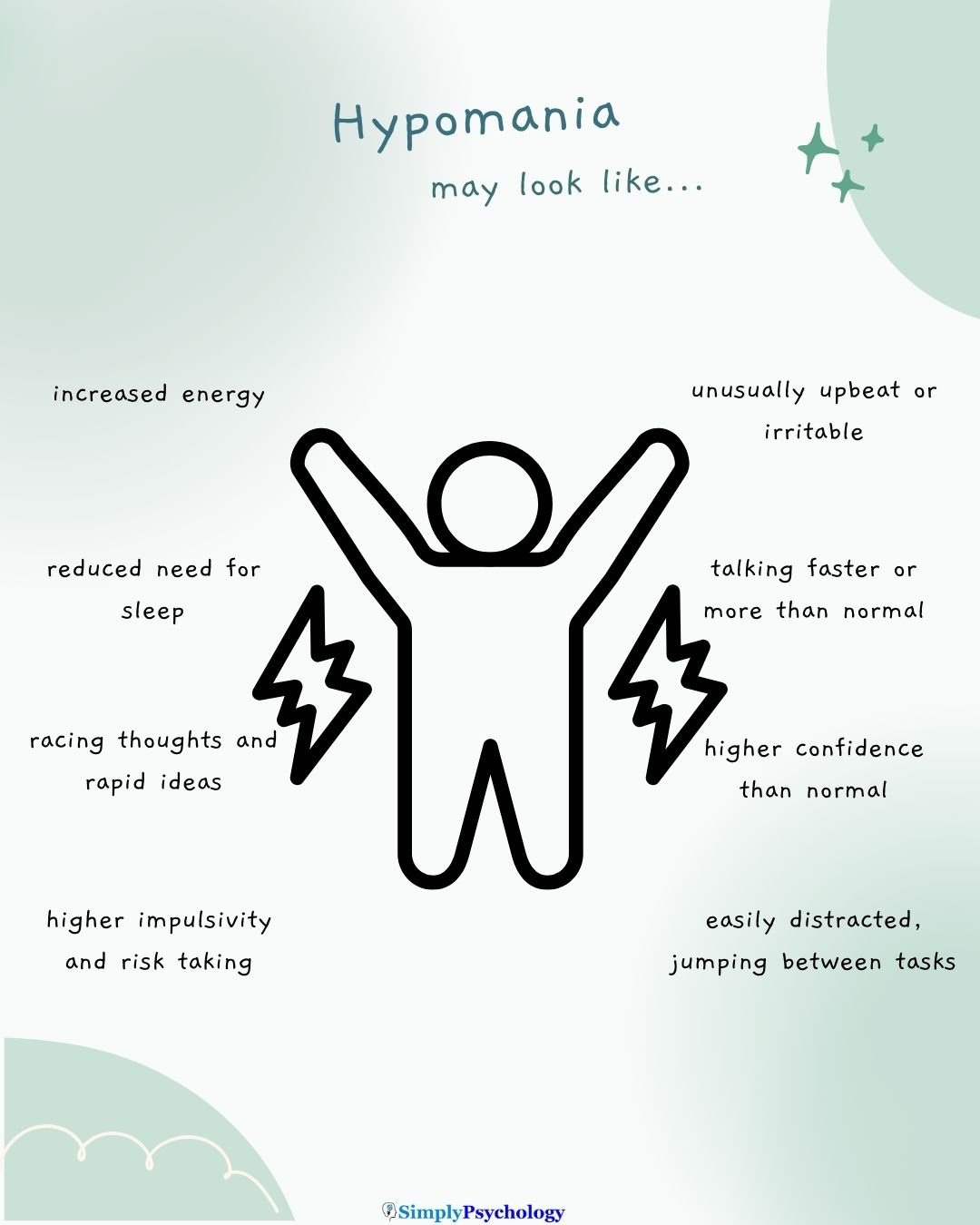

Key Symptoms and Behavioral Signs

Hypomania presents with a distinct shift in behavior and energy. Common symptoms may include:

- Elevated or irritable mood: Feeling unusually upbeat or easily frustrated.

- Increased energy or activity: More physical or mental activity than normal.

- Reduced need for sleep: Sleeping 3–4 hours but still feeling rested.

- Rapid speech: Talking more and faster than usual.

- Racing thoughts: Mind feels overstimulated or flooded with ideas.

- Increased confidence or grandiosity: Overestimating abilities or importance.

- Distractibility: Easily pulled off task or overwhelmed by stimuli.

- Risky behavior: Impulsivity in spending, sex, or driving.

Symptoms must last several days and clearly deviate from one’s typical behavior. They’re noticeable to others, even if the person feels fine.

What Causes Hypomania?

Hypomania doesn’t have a single cause. It typically arises from a mix of biological, genetic, and environmental factors:

- Genetics: Bipolar disorder often runs in families [NIMH].

- Brain chemistry: Imbalances in neurotransmitters like dopamine may contribute.

- Sleep disruption: Losing sleep can trigger episodes.

- Stress or major life events: Emotional upheaval can spark symptoms.

- Substances: Antidepressants, stimulants, or recreational drugs may play a role.

- Seasonal changes: Some experience hypomania during spring or summer.

Only a licensed mental health professional can determine the cause and rule out other conditions.

How Hypomania Can Impact Daily Life

Social Relationships

Hypomania can make someone more outgoing, flirtatious, or talkative. This may enhance social life initially.

However, impulsivity and irritability can lead to conflict. One blogger described becoming “far less kind” as their episode progressed:

“While I try not to ‘snap’ back at people, I am not always successful . . . I become far less happy, joyful, and kind. I dislike being criticized in any which way.”

Work or School

Increased productivity may impress others, but focus is often short-lived. Tasks may be abandoned, deadlines missed, or conflicts arise from overconfidence.

A user shared that they keep “busy like a bee… sometimes overworking, and people might think it looks good because you are working more.”

Finances

Spending sprees or risky investments are common. Hypomania may lead to excessive generosity or impulsive financial decisions. These actions often result in debt, regret, or conflict with loved ones.

Long-Term Stability

Left untreated, hypomania can create patterns of instability. Frequent mood swings, impulsive actions, and strained relationships can disrupt careers, education, and personal growth.

Hypomania and Bipolar Disorder

Hypomania is a defining feature of bipolar II disorder, which involves alternating episodes of hypomania and depression. In contrast, bipolar I disorder includes full manic episodes, which are more severe and may involve psychosis or hospitalization.

In bipolar II, the depressions can be severe, even though the highs are less extreme. Many people spend more time depressed than hypomanic, and diagnosis often occurs only after a depressive episode.

Another condition, cyclothymia, involves chronic mood fluctuations without meeting full criteria for hypomania or major depression.

Accurate diagnosis requires a complete psychiatric history. A single hypomanic episode, especially if triggered by medication, doesn’t automatically mean bipolar disorder. Clinicians assess patterns over time.

Hypomania Vs Mania

While hypomania and mania can affect a person’s behavior and mood, some differences exist.

Hypomania is considered a less severe form of mania, still causing problems in life, but not to the extent that mania can. Hypomania usually lasts a shorter period than mania, usually a few days, whereas mania can last for a week or more.

| Mania | Hypomania |

|---|---|

| Typically lasts at least a week | Usually lasts a few days to a week |

| May require hospitalization | Does not typically require hospitalization |

| Significant impairment in functioning | Mild impairment in functioning |

| May experience psychotic symptoms | Rarely includes psychotic symptoms |

| Excessive risk-taking behavior | Risk-taking behavior may be present |

| Euphoria or extreme irritability | Euphoria or mild irritability |

| Often abrupt | Can be gradual or abrupt |

| Little need for sleep or insomnia | Decreased need for sleep or insomnia |

| Often requires medication and therapy | May require medication and therapy |

| May progress to a full manic episode | Does not progress to a full manic episode |

When to Seek Help

You should speak with a professional if:

- Behavior causes problems at work, school, or in relationships.

- You experience risky or impulsive behavior.

- Sleep is significantly reduced without fatigue.

- You cycle between high and low moods.

- Loved ones express concern about changes in your behavior.

- You experience any signs of psychosis or suicidal thoughts.

Early intervention can prevent escalation and improve long-term outcomes. If you’re unsure where to start, talk to your primary care doctor or find a provider through directories like Psychology Today or SAMHSA’s treatment locator. In the UK, consult your NHS GP or use NHS mental health services.

Treatment Options (Overview Only)

Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps identify triggers and challenge impulsive thoughts. Psychoeducation teaches individuals how to manage symptoms and prevent relapses. Therapy can also support family communication and emotion regulation.

Medication

Mood stabilizers like lithium or valproate, and certain antipsychotics, can reduce symptoms and prevent recurrence. Antidepressants are typically avoided unless combined with a mood stabilizer to prevent triggering hypomania.

Medication plans vary. Only a psychiatrist can recommend the right approach.

Self-Care

Routine sleep, stress management, regular exercise, and avoiding alcohol or drugs can reduce the frequency and severity of episodes.

Many find it helpful to track their mood or maintain a daily structure. Support from peers and family also plays a vital role.

It’s worth emphasizing that treatment plans vary by individual. One person might do well with therapy and strict lifestyle management without medications, especially if their episodes are mild. Another person might need to be on a mood stabilizer indefinitely to prevent frequent mood episodes. There’s no one-size-fits-all, and it often takes time (and some trial and error) to find the right approach.

Final Thoughts

Hypomania can feel energizing and productive, but it’s a sign of an underlying mood disorder. Recognizing the symptoms and seeking help early can reduce the risk of escalation, depression, or life disruption.

Many people with bipolar II live stable, fulfilling lives through a combination of therapy, medication, and self-care. If you see yourself or someone else in these descriptions, speak with a qualified mental health provider.

Getting help is not a sign of weakness. It’s a proactive step toward clarity, health, and peace of mind.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes and does not substitute for professional medical advice. If you have concerns about your mental health, please consult a qualified provider.

Related Articles

National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. Updated January 2020.

References

Dailey, M. W., & Saadabadi, A. (2018). Mania.

Phelps, J. (2017, February 7). A More Nuanced View of Hypomania. Psychiatry Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/more-nuanced-view-hypomania

Proudfoot, J., Whitton, A., Parker, G., Doran, J., Manicavasagar, V., & Delmas, K. (2012). Triggers of mania and depression in young adults with bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 143(1-3), 196-202.