A manic episode is a period of unusually elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, often accompanied by increased energy and activity. It’s commonly associated with bipolar disorder, a condition marked by shifts between emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression).

Symptoms of mania may include inflated self-esteem, reduced need for sleep, rapid speech, racing thoughts, distractibility, intense goal-setting, and impulsive or risky behavior. These experiences can affect judgment, relationships, and daily functioning.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or mental health condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this site.

Episodes may begin suddenly and vary in duration, sometimes lasting several weeks or months. In some cases, mania may involve symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations or delusional thinking.

While the causes of mania can vary, factors like family history, significant life stressors, or sleep disruption may increase the likelihood of an episode. It’s also important to note that symptoms need to represent a clear change from someone’s usual behavior to be recognized as mania.

“The mood elevations of bipolar (mania or hypomania) are not always the grandiose, feeling on top of the world experiences that people sort of classically think of,”

Wendy Marsh, director of the Bipolar Disorders Specialty Clinic.

Mania vs. Hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes but with the same signs. Hypomania is not considered as intense as mania, with mania causing more noticeable problems for personal and social functioning.

With the possibility of mania resulting in psychosis, this can make the effects of this period more long-lasting and may even result in hospitalization.

| Manic Episode | Hypomanic Episode | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | Typically lasts at least one week | Typically lasts at least four consecutive days |

| Intensity | Severe symptoms and impairment in daily functioning | Less severe symptoms and less impairment in daily functioning |

| Psychosis | Can include psychotic features such as hallucinations | No psychotic features |

| Hospitalization | Often requires hospitalization for safety | Hospitalization is usually not required |

| Impact | Can significantly disrupt personal and professional life | May have some impact on personal and professional life |

| Risk-taking | Engage in high-risk behaviors without considering consequences | May engage in some risk-taking behaviors |

| Insight | May have limited awareness or denial of illness | Generally aware of the changes in behavior |

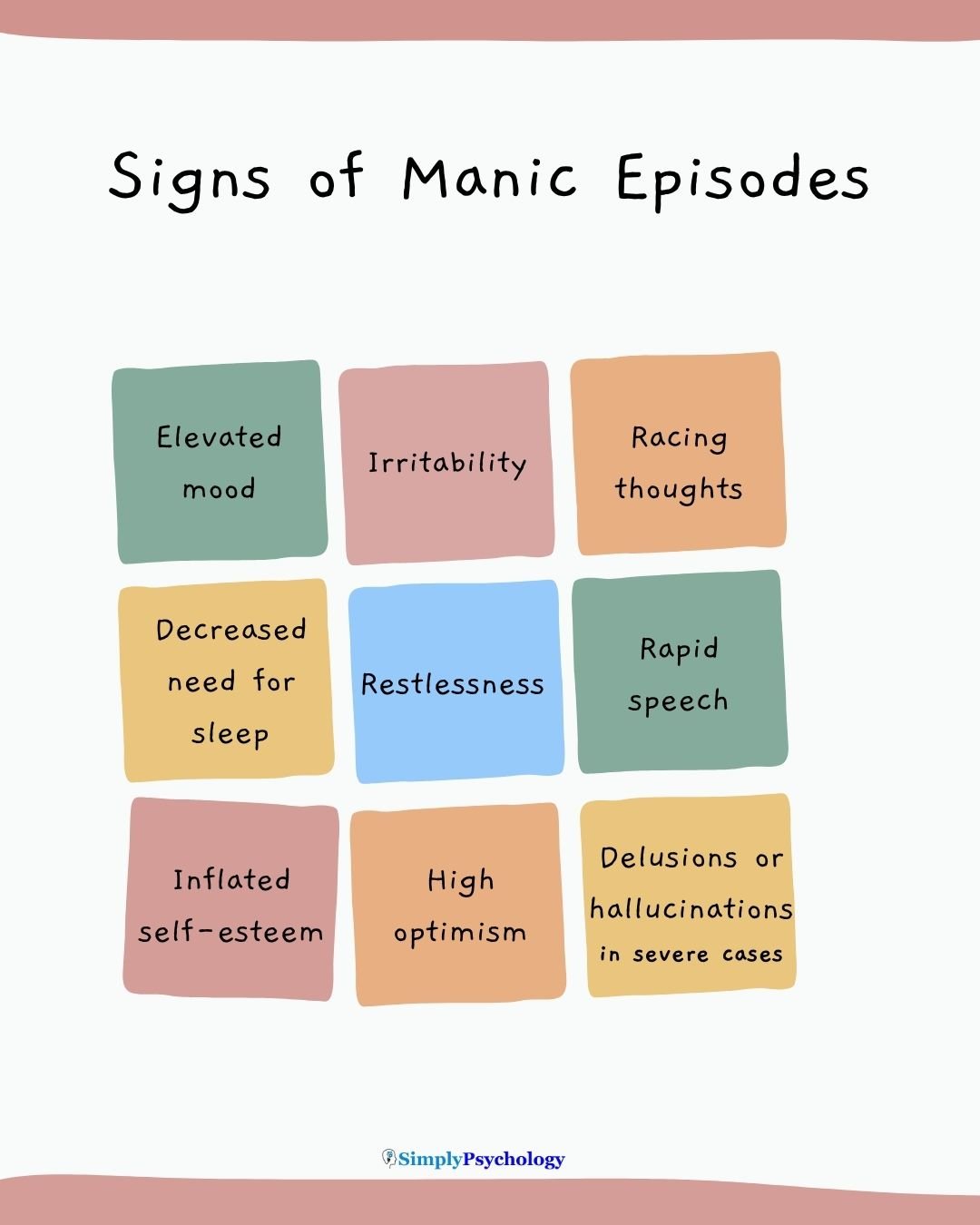

Signs

When considering the signs of mania, it is important to consider the individual’s usual behavior.

Some of the signs of mania may be the usual behaviors displayed by an individual; therefore, they may not necessarily be linked to experiencing a manic episode.

For mania, it is important to look at the considerable changes in behavior from normal. Below are some of the signs that can be associated with mania.

- Irritability and hostility – an individual experiencing mania may display much more irritability than usual. They may quickly start arguments and be easily annoyed by others and their environment.

- Overly energetic – someone experiencing a manic episode may become restless and search for ways to work off their surplus of energy. They may attempt to do many tasks at once or take on several different projects, experiencing bursts of productivity.

- More talkative than usual – a common sign of mania is that the individual may be talking loudly and rapidly. It is important to note that this should be different from their normal volume and speed of talking, as many people talk loudly and fast normally, but would not be considered as experiencing mania.

- Easily distracted – during a manic episode, individuals may be unable to focus on the task at hand. They may find it difficult to focus and constantly get distracted by various things.

- Increased sexual desire – being hyper-sexual is a common sign of mania. Individuals experiencing this may seek out sexual interactions more than usual and may engage in more risky sexual behaviors due to mania.

- Rapid thinking – while experiencing mania, individuals may find that they are experiencing a lot of thoughts at once, or their thoughts are uncontrollably racing. This may not always be noticeable when observing someone from the outside, as they may not be talking any quicker, but on the inside, they may be having several repetitive thoughts that they cannot handle.

- Risky behaviors – those experiencing a manic episode may engage in more risk-taking behaviors. For example, excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences. This could include spending more money than usual, gambling, binge drinking, or taking drugs.

- Grandiosity – during a manic episode, some people may experience unrealistic feelings of grandiosity. This is defined as an exaggerated sense of importance, especially over others. People experiencing grandiosity may believe they are more powerful, knowledgeable, and superior to others.

- Suicidal thoughts – In some instances, people experiencing mania may experience very low moods, hopelessness, or feeling worthless. This could result in thoughts about death and suicide.

- Excessive religious dedication – an increase in the amount of religious involvement someone usually displays, could be another sign of mania. This can link back to grandiosity as this feeling could be accompanied by religious overtones, such as an individual believing that they were sent by a religious entity.

- Decreased need for sleep – often, people experiencing mania find it difficult to sleep. This may be due to being overly energetic, experiencing rapid thinking, and irritability. Sleep problems are common for those with bipolar disorder, with manic episodes leading to sleep problems and sleep problems encouraging more manic episodes to occur.

- Psychosis – during episodes of mania, individuals may also experience hallucinations, such as seeing, hearing, or smelling things that are not there. They may also experience delusions where they believe things that may seem irrational to others.

Note for Health Care Providers: People with bipolar disorder are more likely to seek help when they are depressed than when they are experiencing mania or hypomania. Taking a careful medical history is essential to ensure that bipolar disorder is not mistaken for major depression.

This is especially important when treating an initial episode of depression, as antidepressant medications can trigger a manic episode in people with an increased chance of having bipolar disorder.

Dr Stephen Ferber explains that there are “conditions that often get labeled as bipolar disorder, but aren’t, including ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and Borderline Personality Disorder… Borderline Personality Disorder, in particular, has a lot of symptom overlap with bipolar disorder but represents a more chronic course and is less episodic.”

Personal insights

“For me mania feels like the unhinged version of myself bouncing off the walls of the reality I’ve worked so hard to create.”

“It feels good at first. Lots of energy, feeling social, top of the world. Then I get irritable, jittery and impatient.”

“For myself, someone with Bipolar 1, manic episodes have included racing thoughts, talking more and faster than usual, decreased need for sleep… when it gets worse feeling elated and grandiose. Basically … you have 4 brains working at the same time.”

“I feel intense amounts of euphoria, like I could never be depressed again. Everything looks beautiful and I am constantly in awe of everything.”

Treatment

Below are some of the possible treatments associated with managing manic episodes. Keep in mind this is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice:

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics generally work by blocking a subtype of the dopamine receptor known as D2. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a vital role in mood, so blocking D2 receptors should work to balance out mood.

Some types of antipsychotics are aripiprazole (Abilify), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), and risperidone (Risperdal).

Lithium

Lithium is a type of medication often used for the long-term treatment of mania to reduce how frequently and severely the episodes are experienced. Lithium works by stimulating the glutamate receptor NMDA to increase glutamate availability.

Glutamate is essential for the normal functioning of the brain. Types of lithium include Cibalith-S, Eskalith, and Lithane.

Valproate

Valproate is a type of anticonvulsant medication usually prescribed for epilepsy, but has shown effectiveness in treating some of the signs of mania (being over-excited, overactive, irritable, and distracted).

This works on the brain by increasing the amount of a chemical called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which blocks the transmission across neurons in the brain and has a calming effect as a result.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is also a treatment that can help individuals with mania identify when their moods are changing. Mental health professionals, such as a psychotherapist, can also identify the triggers that may cause a manic episode so that moods can be better managed.

Therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) can help individuals to find ways to manage and cope with their mania, understand it better, and work to find methods to help reduce signs when they are noticed.

Other methods that can be used to manage a manic episode when they occur are some lifestyle changes that individuals can do on their own. These can include:

- Maintaining a sleep schedule – “It is very well documented that not sleeping enough hours by itself can trigger an episode, without any other issues,” Dr. De Faria says.

- Reduce stress at home and work – if able to, it may be advised to keep regular working hours to avoid getting too stressed. Making time to relax and do an activity that is enjoyable to the individual could help to prevent this build-up of stress.

- Keeping a mood diary – keeping track of their mood daily could help individuals to see whether they are heading towards a manic episode. If the individual notices mood changes significantly or some warning signs of mood about to change, they can then seek treatment earlier.

- Not using alcohol or illegal drugs – cutting out alcohol and illegal drugs can help avoid triggering a manic episode or making an episode worse. As alcohol and drugs can interfere with sleep and mood, it is not advisable to consume these if at risk of mania.

- Support networks – during a manic episode or before one comes on, it may be useful to get help from friends and family members. This can be particularly helpful if someone is having trouble telling the difference between what is real and not real (psychosis). Having a support network of people can help individuals to talk through what is real, and they may be able to talk them around or alleviate some of the stress that may trigger an episode.

Do you or a loved one need mental health support?

USA

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

Further Information

National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. Updated January 2020.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.; 2013.

Barden, E. P., Polizzi, C. P., Vizgaitis, A. L., Bottini, S., Ergas, D., & Krantweiss, A. R. (2023). Hyperactivity or mania: Examining the overlap of scales measuring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders in an assessment context. Practice Innovations, 8(2), 102–115.

Carbray JA, Iennaco JD. Recognizing signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1479. doi:10.4088/JCP.14073gc1c

Daly, I. (1997). Mania. The Lancet, 349(9059), 1157-1160.

Gold AK, Sylvia LG. The role of sleep in bipolar disorder. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:207-14. doi:10.2147/NSS.S85754

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/table/ch3.t7/