Panic disorder is an anxiety condition marked by repeated and unexpected panic attacks. A panic attack is a sudden surge of intense fear, often with physical and emotional symptoms such as a racing heart, chest tightness, dizziness, or a sense of impending doom.

Normally, the body’s fight-or-flight response activates when there is real danger. In panic disorder, this alarm system misfires, triggering extreme fear in situations where most people would not feel threatened.

For a diagnosis of panic disorder, these attacks occur recurrently and are followed by ongoing worry about future attacks or changes in behavior, such as avoiding certain places.

Attacks usually peak within 10 minutes and, while not life-threatening, can feel overwhelming and seriously affect daily life.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, panic disorder affects about 2.7% of U.S. adults each year, with symptoms often starting in young adulthood (ages 20–24) and being more common in women than men.

Quick Tips: Coping with a Panic Attack

If you’re having a panic attack right now, here are a few grounding steps you can try:

- Breathe slowly: Inhale through your nose for 4 seconds, hold for 2, exhale through your mouth for 6.

- Ground yourself: Focus on 5 things you can see, 4 you can touch, 3 you can hear, 2 you can smell, 1 you can taste.

- Release tension: Gently tense and relax your muscles, starting with your feet and moving upward.

- Visualize calm: Picture a safe or soothing place, and imagine yourself there until the intensity eases.

Remember: panic attacks feel frightening but are not life-threatening. If you experience them often, consider reaching out to a healthcare professional for support.

Signs of Panic Disorder

What a Panic Attack Feels Like

Panic attacks are sudden episodes of overwhelming fear that trigger intense physical and emotional reactions, even when there is no real danger. Many describe them as feeling out of proportion to the situation.

Common experiences include a racing heart, shortness of breath, dizziness, or a sense of impending doom. For some, the sensations are so severe that they feel like a heart attack. As one person explained:

“It always starts with a sense of doom and literal clouded vision… followed by a compression in my chest… I feel literally locked, like even if I wanted to move my arms or my legs or walk away from a situation, that I couldn’t.”

Tony

The fear of having another attack can itself trigger new episodes, creating a cycle of worry and avoidance.

Physical and Emotional Symptoms

Panic attacks can involve a wide range of symptoms, which may include:

- Palpitations, chest pain, or pressure

- Sweating, trembling, or chills

- Shortness of breath or choking sensations

- Nausea or stomach distress

- Dizziness or light-headedness

- Tingling or numbness in the body

- Feelings of detachment from self or surroundings

- Extreme fear of losing control, going “crazy,” or dying

How long do panic attacks last?

Most panic attacks last 5 to 20 minutes, with symptoms peaking within about 10 minutes. In rare cases, they may last longer than an hour.

Because they strike without warning, panic attacks can severely disrupt daily life. Some people begin avoiding social settings, public places, or even leaving the house for fear of another attack.

Types of Panic Attacks

For panic disorder, there are two main types of panic attacks: unexpected and expected.

Unexpected Panic Attacks

Unexpected panic attacks are the most commonly experienced by people with panic disorder. These can occur suddenly, without warning or any known trigger.

These can even happen when the person is relaxed or emerging from sleep (nocturnal panic attack) and not experiencing anxiety.

‘At one point when I was talking (to my girlfriend) I thought ‘Oh I don’t feel good‘… and then it was like this overwhelming feeling of stress… it happened all very quickly. Once you get that feeling, it just happens immediately.’

Matt

Expected Panic Attacks

Expected panic attacks are more likely to be predicted. They can often occur when exposed to a situation that the person finds fearful.

For instance, someone may have a panic attack when performing on stage or when giving a speech.

Diagnosis

Because the symptoms of a panic attack can feel very similar to a heart attack or other medical emergencies, many people first seek urgent medical care.

Only a qualified healthcare professional can confirm whether symptoms are due to panic disorder or another condition.

Doctors may run tests such as blood work or an electrocardiogram (ECG) to rule out medical causes. If no urgent health issue is found, individuals may be referred for a mental health evaluation.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), panic disorder involves:

- Recurrent, unexpected panic attacks.

- Persistent worry about future attacks for at least a month.

- Changes in behavior (e.g., avoiding certain places or situations) linked to fear of attacks.

Distinguishing Panic Disorder from Other Conditions

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): involves chronic, excessive worry across many areas of life, not sudden surges of intense fear.

- Social Anxiety Disorder: panic-like symptoms may occur, but they are specifically tied to social situations and fear of embarrassment.

- Specific Phobias: panic attacks happen only in response to a particular trigger (e.g., flying, spiders), whereas panic disorder attacks can occur unexpectedly.

Mental health professionals also rule out other explanations, such as substance effects, medical conditions, or overlapping disorders like OCD or PTSD.

This section is for informational purposes only. If you experience panic attacks or severe anxiety, seek professional guidance for an accurate diagnosis and support.

Biology and Psychology of Panic

Panic attacks involve a mix of biological, emotional, and psychological reactions, with fear at the core.

Biological Reactions

When faced with danger, the body activates the fight-or-flight response—increasing heart rate, breathing, sweating, and muscle tension.

In panic disorder, this alarm system misfires, triggering the same intense physical reactions even when no real threat exists.

Breathing changes, such as hyperventilation, can lower carbon dioxide levels in the blood, leading to dizziness, lightheadedness, or muscle stiffness. These sensations may then be misinterpreted as signs of an oncoming attack, fueling more fear.

Psychological Reactions

People with panic disorder often monitor their bodies closely for signs of anxiety.

Normal sensations may be misread as dangerous, leading to catastrophic thoughts such as “I’m going to faint,” “I’m losing control,” or “I might die.” This cycle of fearful thinking makes future panic more likely.

Behaviors That Maintain Panic

In response, many people develop avoidance (e.g., steering clear of public transport, exercise, or busy places) or safety behaviors (such as carrying medication, planning escape routes, or seeking reassurance).

While these strategies provide short-term relief, over time, they can make panic worse by reinforcing the belief that the sensations are unsafe and unmanageable.

Causes and Risk Factors of Panic Disorder

The exact cause of panic disorder isn’t fully understood, but research suggests that a mix of biological, psychological, and environmental factors play a role.

Biological Factors

Genetics and brain functioning may contribute. The risk can be higher for those with a family history of panic attacks or panic disorder, a temperament that is more sensitive to stress or prone to negative emotions.

Anxiety Sensitivity

Some people are particularly sensitive to the physical sensations of anxiety, such as a racing heart or dizziness.

Psychologist Jasper Smits explains, “Anxiety sensitivity is an established risk factor for the development of panic and related disorders.”

This sensitivity can make normal bodily changes feel threatening, triggering panic.

Trauma and Stress

Exposure to traumatic events or ongoing stress may also increase risk.

A review by Berenz et al. (2018) found evidence linking traumatic experiences with later panic symptoms, noting multiple lines of evidence supporting a relationship between trauma exposure and panic psychopathology.

Lifestyle and Environment

Stimulants like caffeine, irregular sleep, or high-stress environments can make panic more likely, especially for those already vulnerable.

Overall, panic disorder often develops through a combination of inherited risk, heightened sensitivity to bodily sensations, stressful life experiences, and environmental triggers. While not everyone exposed to these factors develops panic disorder, they can increase vulnerability.

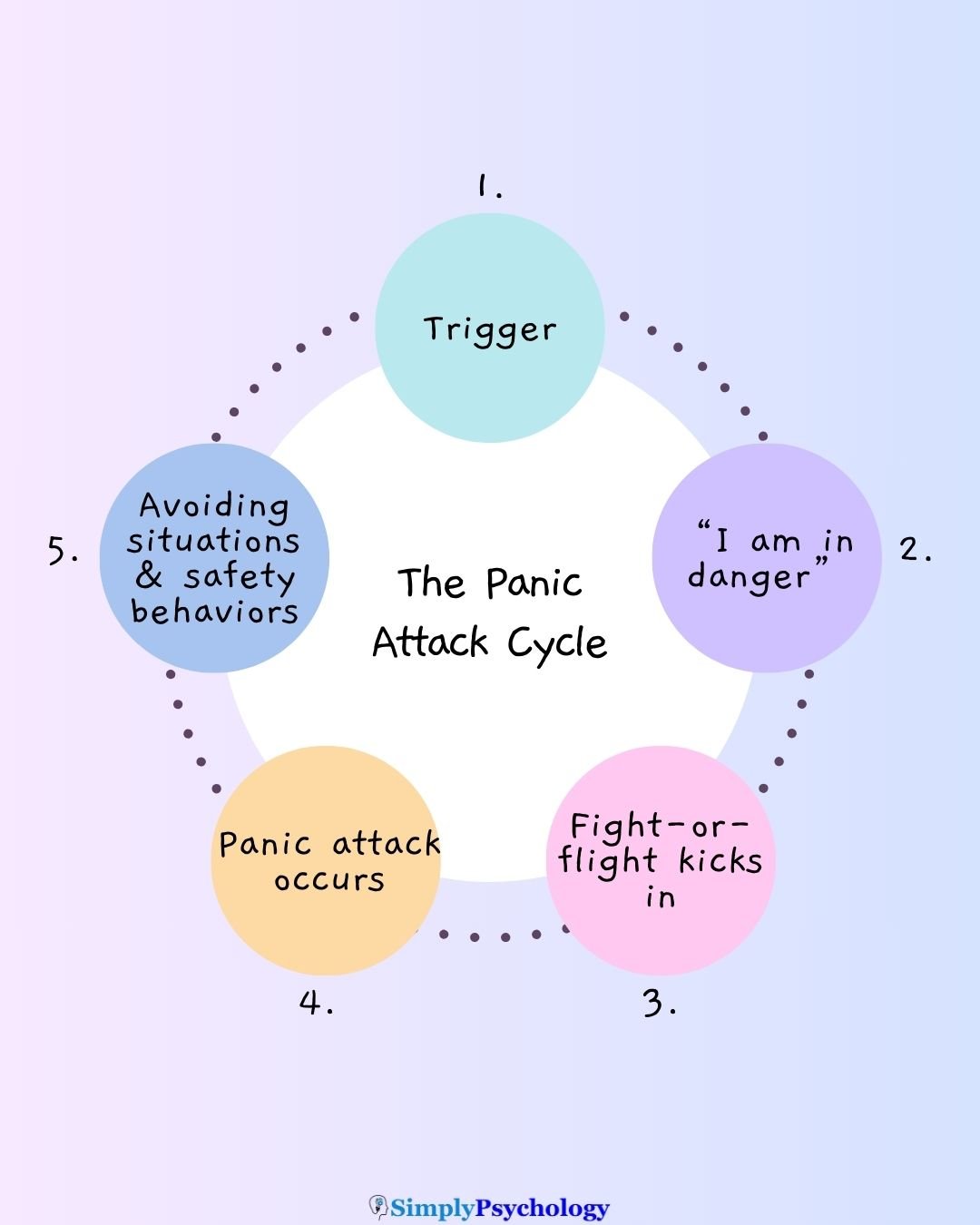

The Cycle of Anxiety

For people with panic disorder, anxiety often follows a repeating cycle.

Avoidance

When panic attacks are feared, it is common to avoid certain places or activities. While this brings short-term relief, it can increase anxiety over time and make situations harder to face later.

Safety Behaviors

Some people rely on “safety behaviors” such as carrying medication, planning escape routes, or always bringing someone along. These may feel protective, but can unintentionally reinforce the belief that panic symptoms are dangerous.

Breaking the Cycle

Recovery often involves gradually facing feared situations without avoidance or safety behaviors. This process, known as graded exposure, helps people learn that anxiety naturally peaks and subsides, building confidence over time.

Graded exposure is a core technique in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Treatment

There are several evidence-based approaches for managing panic disorder. The most common include psychotherapy and, in some cases, medication.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is often considered a first-line therapy for panic disorder. It helps people notice unhelpful thought patterns and behaviors—such as catastrophic thinking or avoidance—and gradually replace them with more balanced ways of responding.

Techniques like graded exposure may be used to face feared situations step by step, reducing reliance on safety behaviors over time.

Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PFPP)

PFPP is a psychodynamic approach that explores underlying emotional conflicts and past experiences that may contribute to panic.

The goal is to bring unconscious fears into awareness so they can be understood and managed more effectively.

Medication

Medication may also be prescribed to help manage symptoms. Common options include:

- Antidepressants such as SSRIs (e.g., sertraline, fluoxetine) and SNRIs (e.g., venlafaxine).

- Anti-anxiety medications like benzodiazepines, typically used for short-term relief due to the risk of dependence.

Medication choices vary, and effects can take time to appear. Side effects are possible, so decisions about medication should always be made with a qualified healthcare professional.

Coping with Panic Disorder

While professional treatment is often important, there are also everyday strategies that may help people manage panic disorder.

These can support overall well-being and provide tools to handle attacks when they happen.

Lifestyle Approaches

- Exercise: Regular physical activity, such as walking or aerobic exercise, has been shown to reduce overall anxiety levels.

- Sleep: Sticking to a consistent sleep routine can lower vulnerability to panic symptoms.

- Nutrition: Limiting caffeine, alcohol, and excessive sugar may help reduce triggers for anxiety.

- Relaxation practices: Mindfulness, yoga, or meditation can promote calm and help regulate stress.

Coping in the Moment

When panic strikes, grounding strategies can reduce the intensity of symptoms:

- Breathing exercises (slow, deep breaths to counter hyperventilation).

- Grounding techniques (focusing on physical sensations, such as pressing feet into the floor).

- Progressive muscle relaxation (tensing and releasing muscle groups to ease body tension).

- Visualization (imagining a calm or safe place).

Support from Others

Having supportive people nearby can make panic attacks feel less overwhelming. A calm companion can offer reassurance, encourage deep breathing, or simply provide grounding by being present.

Supportive friends or family may also help encourage seeking professional treatment when needed.

‘My partner asked, ‘Do you need me to do anything for you right now?‘… I just needed to be by someone. I didn’t need them to say anything to me but to be by someone else who was grounded at the time who clearly was not experiencing the panic that I was experiencing. And eventually, that got me to a place where I could mirror her… I was just trying to get myself to that place.’

Tony

Can Panic Disorder Be Prevented?

While there’s no guaranteed way to prevent panic disorder entirely, many experts agree that certain steps can significantly reduce the risk of escalation after early panic attacks.

Regular exercise, consistent sleep, balanced nutrition, and relaxation practices are often recommended. As Dr. Swantek puts it: “Really, just about any regular physical activity … help reduce anxiety.”

Seeking help early is also key. When initial panic attacks occur, speaking to a qualified therapist or mental health professional can help prevent panic from becoming more frequent or disabling.

Building healthy coping strategies—such as mindfulness, stress‐management, and learning to notice and challenge unhelpful thoughts—can build resilience.

Experts stress that lifestyle adjustments are not replacements for professional care, but they can serve as protective factors.

If you’re experiencing panic attacks or severe anxiety, it’s important to consult a healthcare provider who can evaluate your situation and recommend the best plan.

Do you need mental health support?

USA

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Berenz, E. C., York, T. P., Bing-Canar, H., Amstadter, A. B., Mezuk, B., Gardner, C. O., & Roberson-Nay, R. (2018). Time Course of Panic Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Onsets. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(5), 639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1559-1

Hutton, M. (2020, January 1). MY FIRST PANIC ATTACK | What it Feels Like to Have a Panic / Anxiety Attack. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dK9D-2kAj9o&ab_channel=MattHutton

Lattari, E., Budde, H., Paes, F., Neto, G. A. M., Appolinario, J. C., Nardi, A. E., Murillo-Rodriguez, E. & Machado, S. (2018). Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety symptoms and cortical activity in patients with panic disorder: a pilot study. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH, 14, 11.

Locke, A. B., Kirst, N., & Shultz, C. G. (2015). Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. American family physician, 91(9), 617-624.

National Institutes of Mental Health. Panic disorder: When fear overwhelms.

Nathan, P., Correia, H., & Lim, L. (2004). Panic Stations! Coping with Panic Attacks. Perth: Centre for Clinical Interventions.

Whatz It Feel Like? (2019, February 6). My panic attacks feel like I am dying [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHvkdbwQNBw&ab_channel=WhatzItFeelLike