Amnesia is a selective memory disorder marked by a significant inability to recall past experiences (retrograde amnesia) and/or to learn or retain new information (anterograde amnesia).

It stems from neurological dysfunction—often involving the medial temporal lobe, hippocampus, or diencephalon—or, in some cases, psychological trauma.

Key Takeaways

- Definition: Amnesia is a memory disorder involving difficulty recalling past experiences, forming new memories, or both, and it is distinct from ordinary forgetfulness.

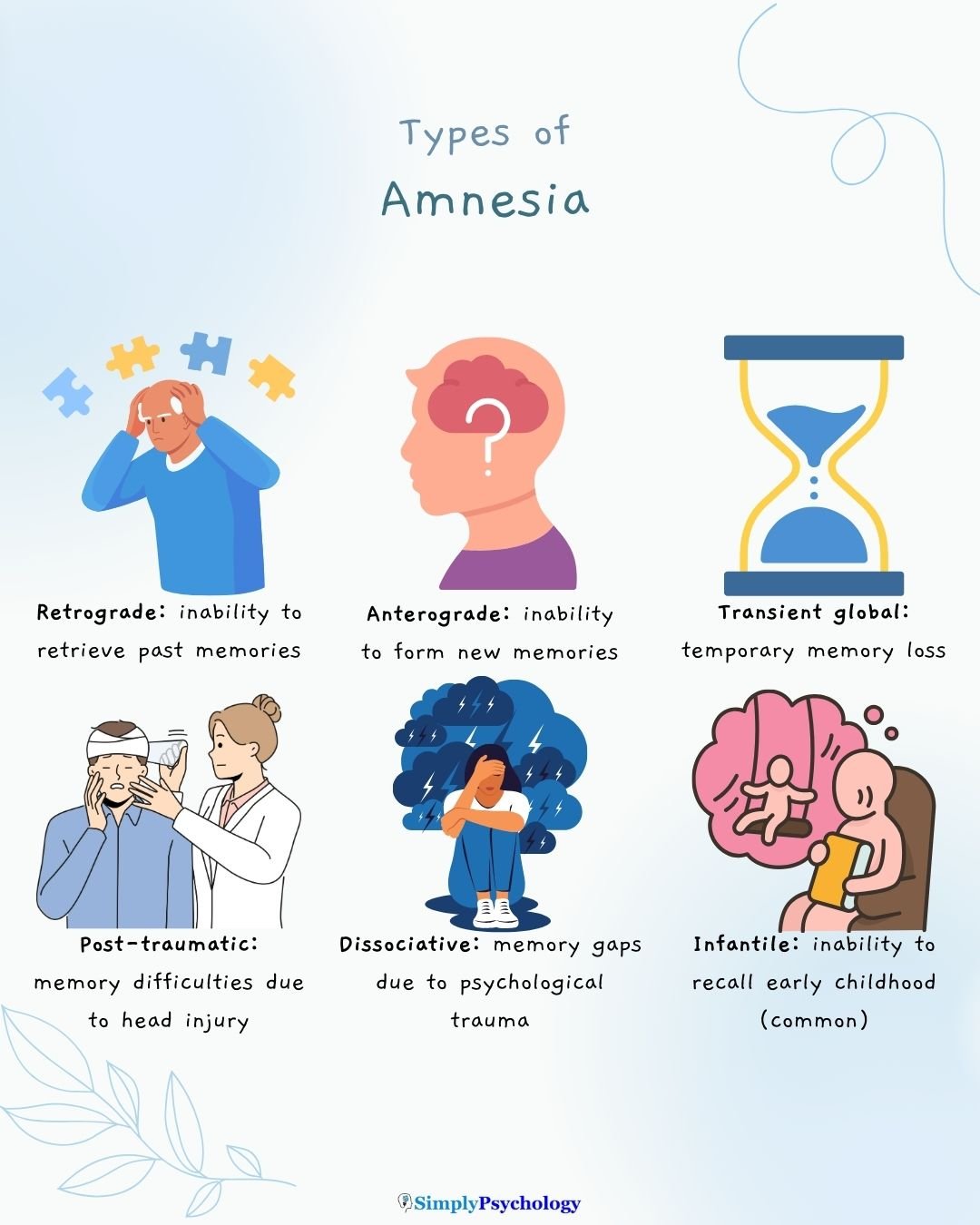

- Types: Different forms include retrograde, anterograde, transient global, dissociative, post-traumatic, and infantile amnesia, each with unique characteristics.

- Causes: Factors such as brain injury, oxygen deprivation, substance use, and psychological trauma can interfere with how memories are stored or retrieved.

- Symptoms: Common signs include memory gaps, disorientation, and confusion, though abilities like language, motor skills, and sense of self usually remain intact.

- Misconceptions: Popular culture often portrays amnesia as a complete loss of identity, but in reality, most people retain large parts of their knowledge and personality.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or mental health condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this site.

Difference from Normal Forgetfulness

Normal forgetting—like failing to recall a name or where one placed an item—is typically fleeting and explained by attention lapses or distractions.

In contrast, amnesia involves deep impairments in forming or retrieving core memories, indicating disruption to memory systems rather than everyday cognitive slip-ups.

Symptoms of Amnesia

Amnesia disrupts memory systems. It may prevent someone from forming new memories (anterograde amnesia) or recalling past ones (retrograde amnesia). In many cases, both occur together.

Additional symptoms often include:

- Confusion or disorientation, especially in unfamiliar settings

- Difficulty recognizing familiar faces or places

- Confabulation, where memory gaps are unknowingly filled with fabricated or misplaced details

Below is a quick reference list of common signs:

- Trouble learning or retaining new information

- Inability to recall past events, especially recent memories

- Difficulty recognizing known individuals or locations

- Confusion about time, place, or personal identity

- Confabulation (unintended creation of false memories)

These symptoms differ notably from normal aging, where occasional forgetfulness (like misplacing keys) is common but does not impair daily functioning or disrupt identity.

In contrast, dementia involves broader cognitive decline affecting reasoning, language, and daily functioning—whereas amnesia remains relatively localized to memory function.

Individuals with amnesia frequently retain substantial non-declarative memory. Procedural abilities—such as motor skills or language syntax—and general intelligence, perception, or self-awareness often remain intact, despite profound deficits in conscious memory recall.

Types of amnesia

There are many different types of amnesia that a person may have. Below is a table outlining some of the most common types:

| Type of Amnesia | Description |

|---|---|

| Retrograde amnesia | Difficulty recalling events or information that occurred before onset of amnesia |

| Anterograde amnesia | Difficulty forming new memories or recalling information learned since onset of amnesia |

| Transient global amnesia | Temporary memory loss lasting several hours, typically not associated with long-term memory problems |

| Post-traumatic amnesia | Caused by traumatic brain injury, can cause difficulty recalling events before and after injury, and difficulty forming new memories |

| Dissociative amnesia | Caused by psychological trauma or stress, may cause difficulty recalling personal information or specific events |

| Infantile amnesia | Inability to remember events from infancy or early childhood due to underdeveloped areas of the brain during this period. |

Retrograde Amnesia

- Involves the loss of memories formed before the onset of amnesia.

- Often affects the most recent memories first (e.g., events just before the amnesia began).

- Older, long-term memories—such as childhood experiences—are usually more resistant.

- Linked to difficulties with memory storage or retrieval.

- In some cases, retrograde and anterograde amnesia occur together.

Anterograde Amnesia

- Involves difficulty forming new memories after the onset.

- Past memories often remain intact.

- Can appear temporarily, such as during alcohol-related “blackouts.”

- May also occur if brain structures involved in memory formation (e.g., hippocampus) are disrupted.

- Tied to problems in encoding or consolidating new information into long-term storage.

Transient Global Amnesia

- A rare, sudden episode of memory loss, usually lasting a few hours.

- During the episode, a person cannot recall recent events or form new ones.

- Deeply ingrained knowledge, such as identity, usually remains intact.

- Often accompanied by confusion or agitation that fluctuates.

- Most common in middle-aged and older adults.

Post-Traumatic Amnesia

- Occurs after a head injury.

- May include memory gaps from minutes or hours before and after the trauma.

- Often accompanied by disorientation and confusion about time, place, or events.

- Can be temporary, but the duration depends on the severity of the injury.

Dissociative Amnesia

- A psychological form of amnesia, often linked to trauma or stress.

- Involves memory gaps about personal life events or identity.

- Can last minutes to years, sometimes leading to profound identity disturbances.

- Memory typically returns, but the original traumatic event may remain inaccessible.

Infantile Amnesia

- The inability to recall early childhood experiences, usually from the first 3–5 years of life.

- Considered a normal phenomenon.

- May relate to brain development and the late maturation of memory and language systems.

It's worth noting that these types of amnesia can overlap, and individuals may experience a combination of signs. Additionally, the severity of signs can vary between individuals, and some may experience signs that are not listed here.

Examples

Retrograde Amnesia After a Car Accident

After a serious car accident, Alex experienced retrograde amnesia, meaning he could not recall events from the days leading up to the crash. While his childhood and older memories remained intact, he struggled to remember recent conversations or daily activities before the accident.

Over time, many of these memories gradually returned, but gaps remained around the incident itself. This highlights how retrograde amnesia often affects the most recent memories first.

Dissociative Amnesia Triggered by Trauma

Following a highly distressing event, Maya developed dissociative amnesia, in which she was unable to recall specific personal details related to the trauma.

Although she could still function in everyday life and retained her skills and identity, the autobiographical gap made it difficult to piece together parts of her life story.

With supportive therapy, she learned coping strategies and began to recover fragments of memory, though some details remained inaccessible.

Causes of Amnesia

Below are some of the possible causes of amnesia:

1. Brain Injury or Damage

Amnesia may result from structural harm to memory-related regions, including the hippocampus, medial temporal lobe, or diencephalon, due to conditions like stroke, tumors, or infections (e.g., herpes‑induced encephalitis).

These disruptions can impair memory storage or retrieval processes.

2. Oxygen Deprivation (Hypoxia)

Periods of reduced oxygen to the brain—such as during cardiac arrest or respiratory failure—can damage CA1 neurons in the hippocampus, critically impairing memory consolidation and leading to lasting amnesia.

3. Substance Use (Alcohol, Medications)

Substances like alcohol or certain medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, sedatives) can interfere with the brain’s memory encoding and consolidation processes.

High alcohol consumption may cause temporary “blackouts,” while long‑term abuse or medication use may cause more enduring memory deficits.

4. Psychological Trauma or Stress

Severe stress or psychological trauma can trigger dissociative amnesia. This effect is thought to result from psychological defense mechanisms protecting the individual from overwhelming experiences, rather than from neurological dysfunction.

How Is Amnesia Diagnosed?

Please note that amnesia can only be diagnosed by a healthcare professional, below is for informational purposes only.

Cognitive / Memory Assessments

Diagnosing amnesia typically begins with neuropsychological testing, often comparing recall versus recognition capabilities.

Individuals with amnesia generally show pronounced difficulties in recalling information, while recognition remains relatively preserved, reflecting specific dysfunction in memory systems such as the medial temporal lobe.

These assessments help differentiate amnestic conditions from other cognitive impairments.

Brain Imaging and Medical Evaluation

While assessment often starts clinically, brain imaging—like MRI—is sometimes used to rule out structural causes, including strokes or lesions affecting memory circuits.

In cases such as transient global amnesia, clinical history and presentation are often sufficient, with imaging reserved only when atypical features suggest alternative causes.

Importance of Ruling Out Other Conditions

It’s essential to exclude other explanations, such as dementia, epilepsy, or metabolic conditions, through medical examination, patient history, and sometimes referral to specialists. This helps ensure that memory loss is correctly identified as amnesia rather than another disorder.

Treatment and Coping Strategies for Amnesia

No Single Cure

Amnesia does not have a universal cure. Management usually depends on the type and cause, with some cases resolving naturally over time (for example, short-term memory gaps after mild head trauma or substance effects). In other cases, memory loss may persist and require longer-term support.

Medical Approaches

Where memory problems stem from physical causes—such as injury, illness, or nutritional deficiencies—treatment often focuses on addressing the underlying issue.

Cognitive rehabilitation is sometimes used to strengthen memory strategies after neurological damage. In certain conditions, medication may be prescribed to support brain health, but these decisions are made by healthcare professionals.

Coping Strategies

For many, daily coping relies on practical memory supports, such as:

- Journals, smartphone apps, alarms, or visual cues

- Consistent routines and structured environments

- Support from family, friends, or caregivers

These coping strategies help people with amnesia compensate for memory gaps and improve quality of life.

Therapy and Adjustment

Therapies can support emotional and cognitive adaptation. Occupational or neuropsychological rehabilitation may teach strategies for learning new information and managing memory aids.

Other forms of therapy—such as cognitive-behavioral or creative approaches—can help individuals process the emotional impact of memory loss and strengthen coping skills.

Prevention and Brain Health

While amnesia itself is not always preventable, maintaining brain health may reduce certain risks.

Research highlights the benefits of regular exercise, a nutrient-rich diet, staying hydrated, mental stimulation, quality sleep, stress management, and protecting the head from injury.

These habits support cognitive resilience and overall wellbeing.

Myths and Misconceptions About Amnesia

Not Typically a “Total Memory Wipe”

Contrary to popular belief, most cases of amnesia do not involve the complete erasure of a person’s past.

Research shows individuals often retain substantial autobiographical or procedural memory, even when facing partial loss of episodic memory.

Identity, Motor Skills, and Language Usually Remain Intact

Many people with amnesia maintain core aspects of selfhood—such as motor skills, basic language, and identity—even while struggling to recall specific events.

Fiction vs. Real-Life Amnesia

Amnesia is frequently dramatized in movies or TV—often showing instant identity loss or cure by a second head injury. In reality, such scenarios are exceptionally rare and medically inaccurate.

Further reading

National Institutes of Health (NIH): Classic and recent advances in understanding amnesia

National Health Service (NHS): Amnesia (Memory Loss)

References

Baxendale, S. (2004). Memories aren’t made of this: Amnesia at the movies. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 329(7480), 1480. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1480

Guadagni, V., Drogos, L. L., Tyndall, A. V., Davenport, M. H., Anderson, T. J., Eskes, G. A., Longman, R. S., Hill, M. D. & Poulin, M. J. (2020). Aerobic exercise improves cognition and cerebrovascular regulation in older adults. Neurology, 94(21), e2245-e2257.

Pross, N. (2017). Effects of dehydration on brain functioning: a life-span perspective. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 70(Suppl. 1), 30-36.