The fawn response is a trauma-driven coping mechanism where a person deals with a threat by people-pleasing—essentially trying to appease or “befriend” the source of danger to avoid harm.

Alongside fight, flight, and freeze, fawning is the fourth “F” of instinctive stress responses. It involves prioritizing others’ needs, moods, and demands, often at the expense of one’s own well-being.

Many autistic individuals recognize this pattern in themselves, especially if they’ve grown up or worked in environments where they felt socially unsafe.

They may become extremely agreeable or helpful as a way to prevent conflict, bullying, or rejection.

What Is the Fawn Response?

Coined by therapist Pete Walker, “fawning” is essentially people-pleasing as a survival strategy.

Instead of fighting back or fleeing, a person in fawn mode copes with fear by trying to stay on someone’s good side. This can mean abandoning one’s own needs and boundaries to keep another person calm or approving.

It’s crucial to understand that fawning is not just being “too nice” or polite—it’s an automatic adaptation when someone feels unsafe.

As trauma expert Dr. Arielle Schwartz explains, the fawn response “involves people-pleasing to the degree that an individual disconnects from their own emotions, sensations, and needs”.

Fawning isn’t a conscious “choice” to be nice; it’s a learned safety reflex. It’s a survival adaptation that helped you stay safe in a hostile situation by making yourself as agreeable and “small” as possible.

The Fawn Response in Autistic People

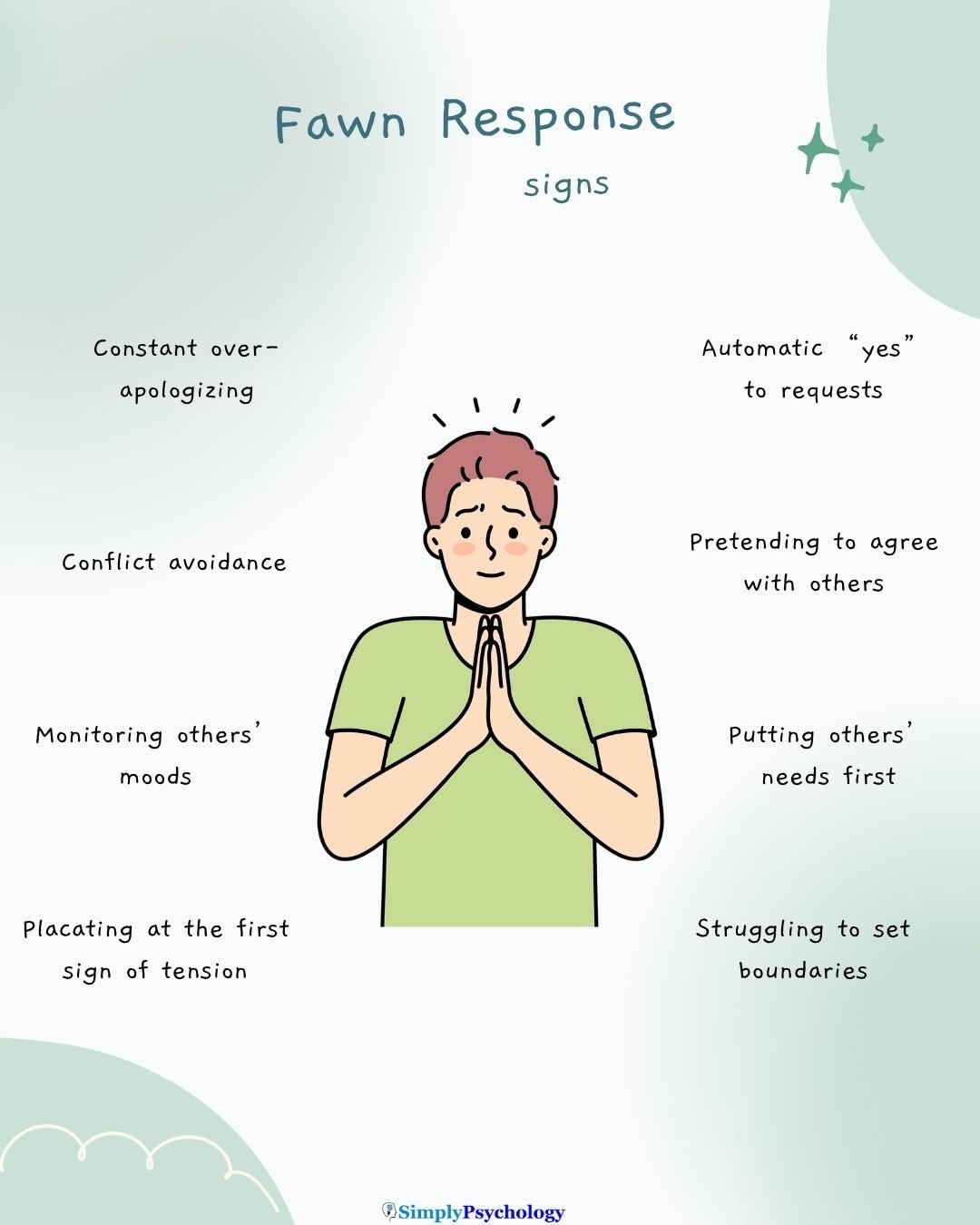

Common fawning behaviors in the autistic community include:

- Overcommitting to others’ needs: Routinely going above and beyond to help or please others, even when exhausted or inconvenienced. Saying “yes” is nearly automatic because displeasing someone feels terrifying.

- Suppressing personal distress: Hiding or tolerating sensory discomfort and ignoring pain or needs, fearing they’ll be seen as a burden. For example, enduring an overwhelming noise rather than asking for a break to avoid “causing trouble”.

- Difficulty with boundaries: Setting boundaries or saying “no” causes intense guilt and anxiety, often leading to profuse apologies if they do decline something.

- Conflict avoidance: Agreeing with others or pretending to share their opinions, even when secretly disagreeing, just to avoid debate or anger. Keeping the peace feels more urgent than honesty.

As one autistic writer shared, after constant rejection, they felt they had to “pretzel or origami myself into what people wanted me to be” because “bullying made being myself unsafe”.

Fawning vs. Masking: A Crucial Overlap

Fawning in autism often overlaps with or is embedded in masking (social camouflaging).

- Masking is the act of hiding or suppressing autistic traits (like forcing eye contact or holding back stimming) to blend in with neurotypical society and avoid discrimination or gain acceptance.

- Fawning is an appeasement response specifically rooted in fear or threat. It is going into full people-pleaser mode to placate a potential threat.

An autistic person might mask by faking a smile, but they fawn by agreeing to everything, never asserting themselves, and actively trying to soothe others’ egos. The key difference lies in the driving emotion:

| Trait | Masking | Fawning |

| Driving Emotion | Desire for acceptance, fear of discrimination | Fear of harm, conflict, or loss of love |

| Behavior Goal | To blend in or appear “normal” | To appease and defuse threat |

| Outcome | Editing or toning down who you are | Erasing yourself altogether to appease others |

Why Are Autistic People Prone to Fawning?

Several factors combine to make an autistic person especially susceptible to developing a fawn response:

Social Trauma and Rejection

Many autistic people can face bullying, exclusion, or harsh criticism simply for being different.

This teaches a powerful, painful lesson: “If I assert myself or show my true quirks, I get hurt or rejected”.

Fawning becomes a shield to preempt conflict or abandonment.

Early Conditioning and “Be Good” Pressure

Autistic individuals may be pressured from a young age to behave “perfectly,” especially autistic girls who are often socialized to be extra polite and compliant.

If natural autistic behaviors are punished, the child learns that the only way to stay safe or earn love is to be exceedingly good and accommodating.

This rejection-sensitive conditioning can become so ingrained that the person feels their survival depends on avoiding disappointment.

Fear of Rejection & Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD)

Autistic people can have an acute fear of rejection. Some also experience Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), an intense emotional pain at any perceived slight, and often drives intense people-pleasing.

This high sensitivity to perceived disapproval naturally feeds fawning behavior.

Feeling “Too Much” or “Not Enough”

Years of negative feedback can instill a belief that one is perpetually “too much” (too intense, too odd) or “not enough” (not social enough).

Fawning emerges as a strategy to manage that fear—by constantly calibrating oneself to what others seem to want, in the hope of finally being “enough” and unobjectionable.

Trauma and Possible Complex PTSD (C-PTSD)

Trauma is alarmingly common in the autistic population; one study found that 32% of autistic adults showed signs of PTSD, compared to just 4% of non-autistic adults.

Fawning is a known coping mechanism for trauma survivors, making it a logical response for many autistic individuals.

Cumulative social and institutional traumas (being repeatedly misunderstood, bullied, or punished) can set the stage for a lifelong fawn response.

The Emotional Cost: Fawning’s Impact on Mental Health

While people-pleasing keeps you safe in the moment, chronic fawning takes a serious toll on mental health.

- Anxiety and Hypervigilance: Living in fawn mode means you are always on guard. You constantly monitor others’ moods, fret over keeping them happy, and worry incessantly about upsetting someone. Physically, the body is in constant stress mode, leading to tension, insomnia, and fatigue.

- Depression and Self-Esteem Damage: Fawning requires continually suppressing your own needs and emotions. By invalidating personal needs, self-worth erodes. Extended masking and people-pleasing are linked to higher rates of depression and suicidal thoughts in autistic individuals.

- Identity Confusion: Long-term fawning can result in losing touch with who you really are. You struggle to answer basic questions about your own feelings or desires, as you’ve spent so long mirroring others.

- Autistic Burnout: The continuous effort of acting, masking, and fawning leads to an intense state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion. The energy reserve is completely drained by the sustained stress of pretending and appeasing.

- Relationship Difficulties: Fawners often end up in unequal or toxic relationships with people who exploit their people-pleasing nature. The fear-driven relating also makes genuine intimacy difficult, reinforcing isolation.

Fawning and Identity: Overlooked and Misdiagnosed

Fawning behavior can fly under the radar, especially due to gendered expectations and intersecting identities.

Gender and Diagnostic Overshadowing

Autistic women, girls, and AFAB (assigned female at birth) individuals are often socialized to be compliant and helpful.

Their tendency to imitate social niceties and fawn leads to being overlooked for an autism diagnosis, with challenges misattributed to anxiety or simply being a “good girl”.

Intersecting Identities

BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and queer or LGBTQ+ autistic folks may layer fawning on top of masking to avoid prejudice or to stay safe in a hostile environment.

Their people-pleasing is often misinterpreted as cultural respectfulness or personality, rather than a coping response to an unsafe world.

Trauma Masking Autism (and Vice Versa)

A client’s compliant, passive behavior (fawning) can cause therapists to miss signs of PTSD, assuming it’s just an autistic trait or “shy personality”.

Conversely, autism can mask trauma, because the individual’s trauma response doesn’t fit neurotypical stereotypes (e.g., they become overly accommodating instead of visibly angry or avoidant).

This dual overshadowing means many autistic fawners don’t get the correct diagnosis or support for either condition.

Unlearning the Fawn Response: Steps Toward Healing

Recovery from a fawn response is possible, but it requires gently teaching your nervous system that it’s safe to let go of people-pleasing when it’s not truly needed.

1. Create Safe Spaces to Be Yourself

Identify a person, therapist, or neurodivergent support group where you feel safe enough to drop the people-pleasing act.

Practice authenticity in low-stakes ways—express a dissenting opinion or share a need, and see that you are still accepted.

This positive experience helps rewire your brain’s expectations. Prioritize relationships where you don’t feel on guard.

2. Gradual Boundary-Setting

Start by setting small boundaries daily, like exercising a weak muscle.

- Instead of an automatic “yes,” try saying: “I’ll check my schedule and get back to you.” This buys you time to decide what you want.

- Practice declining something minor, like a meetup you’re too tired for.

- Remind yourself that no one died because you set a boundary.

- Start with safe people, like telling a close friend: “Actually, I prefer a different restaurant”.

- Script and rehearse boundary-setting phrases (“No, thanks,” “I’m not comfortable with that”) to make them easier in the moment.

Each successful boundary, no matter how tiny, should be celebrated as a way to retrain your reflexes.

3. Seek Trauma-Informed, Neurodivergent-Affirming Therapy

A therapist who understands both autism and trauma is key. Look for someone with a neurodiversity-affirming perspective.

Therapy provides a safe space to role-play assertiveness and process the experiences that taught you fawning was necessary, slowly helping to retrain your brain to realize you have choices and deserve respect.

4. Reconnect with Your Body and Emotions

Since fawning requires disconnecting from feelings, start developing habits that ask: “What am I feeling right now? What do I need?”.

- Engage in your preferred stims or sensory comforts (like noise-canceling headphones) to reconnect with your authentic self.

- Use journaling as a private space to voice thoughts and desires you’d normally bury.

- Practices like gentle yoga, breathing exercises, or simple body scans can teach your body what safety and calm feel like.

- The more you tune into your own signals—”I’m upset,” “I disagree”—the harder it becomes to ignore them for someone else’s sake.

5. Educate and Empower Yourself

Reading about topics like autistic masking, C-PTSD, or people-pleasing can give you valuable insight and language for your experience.

Understanding why you developed the coping mechanism gives you the power to consciously choose new ways to cope.

6. Build a Supportive Network

Seek out support groups for trauma survivors or autistic adults to reduce the shame of your struggle.

Let trusted people in your life know you’re working on this.

For instance, you might say, “I’m practicing being more honest about what I want. Can you support me by encouraging me when I speak up?”.

Good friends will often be relieved to see the real you emerge.

Recovery is not linear. If you feel a wave of panic or guilt after asserting yourself, treat it as a sign of progress, not a sign to stop.

You are breaking a deeply ingrained survival pattern, and every bit of practice helps build your “assertiveness muscle” and nudges your brain toward feeling safe being you.

References

Cassidy, S. A., Gould, K., Townsend, E., Pelton, M., Robertson, A. E., & Rodgers, J. (2020). Is Camouflaging Autistic Traits Associated with Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours? Expanding the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide in an Undergraduate Student Sample. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 50(10), 3638–3648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3

Haruvi-Lamdan, N., Horesh, D., Zohar, S., Kraus, M., & Golan, O. (2020). Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: An unexplored co-occurrence of conditions. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320912143