Parenting that is inconsistent, overprotective, or intrusive is one of the strongest predictors of anxious attachment in children.

This kind of care creates confusion: sometimes the parent is unavailable when comfort is needed, yet at other times they are over-involved or controlling when the child is trying to explore.

The result is a deep uncertainty about the caregiver’s availability, which pushes the child to adopt anxious strategies to hold on to closeness.

Childhood Origins

- Inconsistent Care: When parents are warm and responsive at times but distant or unavailable at others, children grow uncertain about reliability. This unpredictability fuels anxiety and a stronger need for attention.

- Overprotective Parenting: Caregivers who hover too closely or interrupt independence teach children to link autonomy with guilt or danger, leaving them anxious about exploring on their own.

- Parental Anxiety: Parents preoccupied with their own stress may misread or overlook a child’s needs. Children in this situation often exaggerate their emotions to get noticed.

- Blurred Boundaries and Role Confusion: When children are placed in adult-like roles, such as meeting a parent’s emotional needs, they can feel overwhelmed and insecure in their relationships.

inconsistent caregiving

Anxious attachment (also called resistant or ambivalent) typically develops in early childhood when caregiving feels unreliable.

Parents who are emotionally available at some times but distant or unavailable at others create uncertainty for the child.

Children in this situation grow up unsure whether their needs for comfort and protection will be met, and they adopt an anxious strategy to hold on to their caregiver’s attention.

Key Features of Inconsistent Caregiving

- Unpredictable Responsiveness: Caregivers may sometimes ignore a child’s signals or respond too late, while at other times they are attentive. For the child, this means comfort feels unreliable.

- Delayed or Ineffective Responses: Mary Ainsworth’s research found that some caregivers delayed responding to cries or focused on routines instead of the child’s needs, leaving infants feeling unsettled rather than comforted.

- Misreading the Child’s Needs: Caregivers may enjoy closeness but fail to notice when the child truly needs comfort. This “imperceptiveness” can be just as damaging as inconsistency. A child in this situation may feel they must amplify their signals – crying louder or clinging tighter – to finally be noticed.

- Parent’s Own Emotional Struggles: Inconsistent care often reflects a parent’s own anxieties. For example, a parent preoccupied with their own worries or unresolved family issues may give care that feels confused – sometimes over-involved, sometimes absent. This leaves the child unsure of what to expect.

Impact on the Child

Because comfort is uncertain, children with this attachment style become hypervigilant, constantly monitoring the caregiver’s presence and reacting strongly to signs of separation.

They develop a strategy of hyperactivation: clinging tightly, crying persistently, and sometimes showing anger to keep their caregiver engaged.

This strategy helps ensure some attention, but it comes at a cost: children remain preoccupied with their caregiver, explore less, and struggle to self-soothe.

Over time, they build an internal working model of relationships marked by insecurity and fear of abandonment.

The Child’s Contribution

While caregiving is the primary factor shaping attachment, a child’s temperament can make them more vulnerable to developing an anxious style.

Temperament refers to inborn traits – such as how easily a baby gets upset, how strongly they react, and how quickly they calm down.

Infants who are naturally more fussy, irritable, or easily distressed may be more vulnerable to developing anxious attachment if caregiving is less than optimal.

In these cases, an especially sensitive caregiver is needed to support secure development.

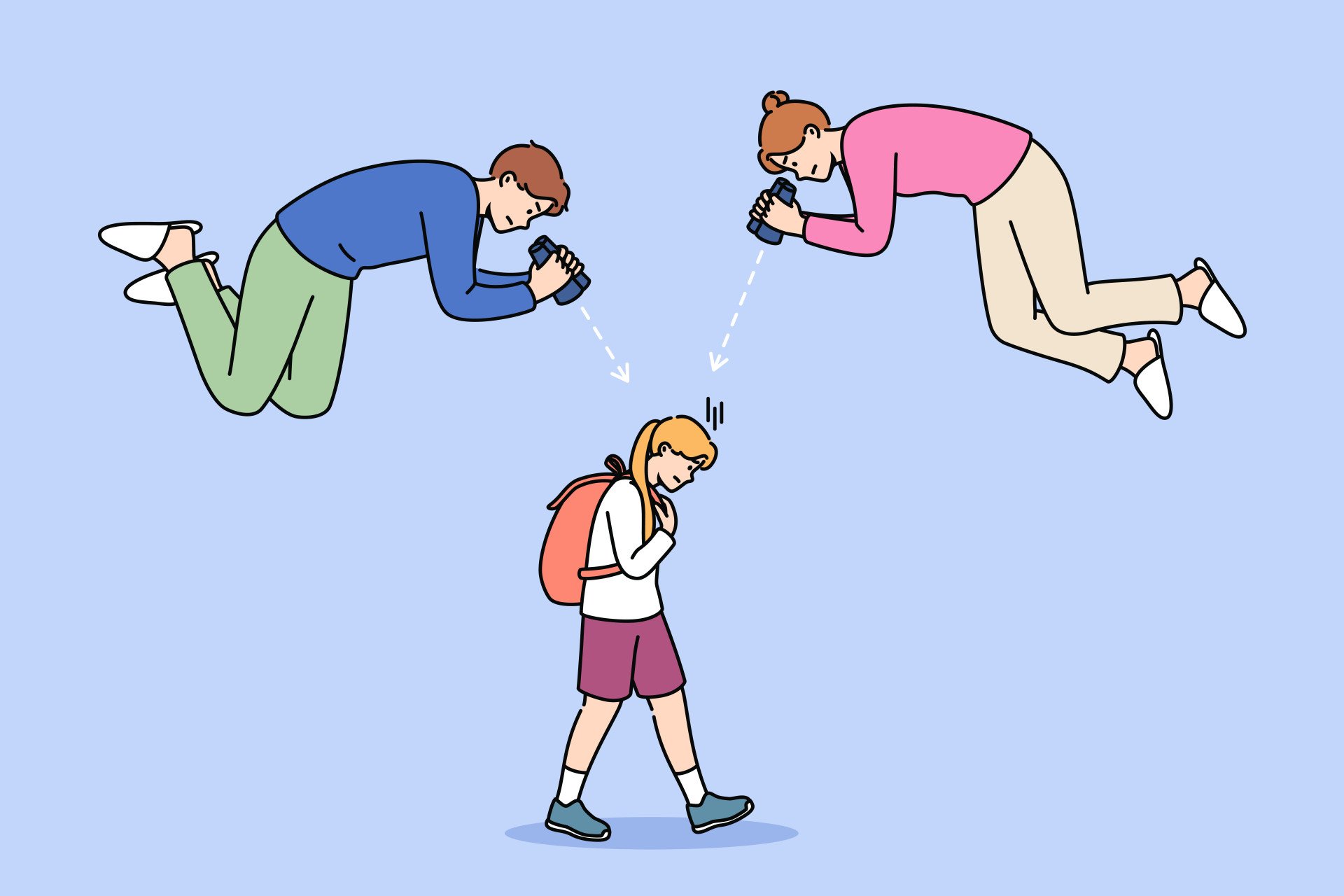

overprotective or intrusive parenting

Overprotective parents limit independence out of worry, while intrusive parents override the child’s signals out of control or unmet needs. Both patterns interfere with autonomy and can foster anxious attachment when combined with inconsistent responsiveness.

Overprotection

Overprotective parents often step in too much, discouraging independence and exploration.

Caregivers may keep the child too close, constantly watching or helping even when the child is capable. While this may come from anxiety or love, it signals to the child that independence is risky.

Over time, the child may feel anxious whenever they try to explore or do things alone.

Because independence feels unsafe, children may grow up fearful of exploring, anxious about separation, and overly reliant on others for comfort.

In adolescence and beyond, this can contribute to anxious attachment patterns, marked by clinginess, fear of abandonment, and difficulty trusting their own abilities.

Overprotective parenting is usually driven by worry.

Parents who fear harm, failure, or distress may step in too often, limiting their child’s independence in an attempt to keep them safe.

What Is “Close Protection” in Parenting?

Close protection is a parenting pattern where a child is kept physically close and constantly monitored.

While it may look like careful supervision, it often crosses into intrusiveness, interfering with the child’s natural need to explore and develop independence.

Parents who practice close protection may frequently pull their child back, issue constant commands, or interrupt their play. They often hover, instruct, and control, leaving little space for the child to make choices. This lack of respect for autonomy can make children feel trapped and overly dependent.

Intrusiveness

Some caregivers show a pattern of mistimed intrusiveness – being unavailable when comfort is needed but intrusive and overinvolved when the child is exploring independently.

Instead of following the child’s lead, they dictate activities, interrupt play, or overstimulate, creating a mismatch between the caregiver’s behavior and the child’s signals.

For the child, this sends confusing messages. Comfort may not come when it’s needed, but independence is also disrupted.

As a result, the child feels torn – closeness can feel overwhelming, yet separation feels unsafe. Over time, this undermines the child’s ability to regulate emotions and to feel confident being independent.

For example, a child might begin exploring a toy, only for the parent to step in, redirect, or “take over.”

In other cases, intrusive parents may push closeness or share emotions on their own terms rather than responding to the child’s cues.

Both patterns leave children feeling a lack of control and make it harder for them to develop self-regulation skills.

Why Parents Behave Intrusively

Intrusiveness is often rooted in a parent’s own anxiety or unmet emotional needs.

- Role reversal: A parent may unconsciously expect the child to meet their emotional needs, reversing the caregiving role.

- Compulsive caregiving: Some parents overwhelm the child with attention not based on the child’s cues, but to meet their own need for closeness.

- Parental anxiety: Caregivers who are anxious themselves may swing between over-involvement and withdrawal, leaving the child confused and insecure.

What Healthy Caregiving Looks Like

By contrast, attuned caregiving means reading and responding to a child’s signals in a timely, sensitive way. A responsive caregiver:

- Provides comfort when the child is distressed, helping them feel safe and understood.

- Steps back when the child is happily exploring, offering encouragement without taking over.

- Supports autonomy by allowing the child to try things independently, while staying available as a secure base.

This balance – comfort when needed and space when not – helps children build both trust in relationships and confidence in their independence.

Sources

Arriaga, X. B., Kumashiro, M., Simpson, J. A., & Overall, N. C. (2018). Revising working models across time: Relationship situations that enhance attachment security. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 71-96.

Beebe, B., Jaffe, J., Markese, S., Buck, K., Chen, H., Cohen, P., … & Feldstein, S. (2010). The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month mother–infant interaction. Attachment & human development, 12(1-2), 3-141.

Belsky, J., & Fearon, R. P. (2002). Early attachment security, subsequent maternal sensitivity, and later child development: does continuity in development depend upon continuity of caregiving?. Attachment & human development, 4(3), 361-387.

Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1415-1434.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(2), 274.

De Wolff, M. S., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta‐analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child development, 68(4), 571-591.

Dunst, C. J., & Kassow, D. Z. (2008). Caregiver sensitivity, contingent social responsiveness, and secure infant attachment. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 5(1), 40.

Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: Four lessons. Current opinion in psychology, 25, 26-30.

Lucassen, N., Tharner, A., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Volling, B. L., Verhulst, F. C., … & Tiemeier, H. (2011). The association between paternal sensitivity and infant–father attachment security: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of family psychology, 25(6), 986.

Madigan, S., Deneault, A. A., Duschinsky, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Schuengel, C., van IJzendoorn, M. H., … & Verhage, M. L. (2024). Maternal and paternal sensitivity: Key determinants of child attachment security examined through meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 150(7), 839.

McElwain, N. L., & Booth-LaForce, C. (2006). Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. Journal of family Psychology, 20(2), 247.

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Fradley, E., & Tuckey, M. (2001). Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42(5), 637-648.

Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2015). Responsiveness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 67-71.

Smith, P. B., & Pederson, D. R. (1988). Maternal sensitivity and patterns of infant-mother attachment. Child development, 1097-1101.

van IJzendoorn, M.H. & De Wolff, M. (1997). “Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment.” Child Development, 68(4), 571-591. (Meta-analysis confirming inconsistent or insensitive caregiving is linked to insecure attachments).

Zeegers, M. A., Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. J. J., & Meins, E. (2017). Mind matters: a meta-analysis on parental mentalization and sensitivity as predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychological bulletin, 143(12), 1245.