Key Takeaways

- Axial coding is the second stage in the coding process of qualitative data analysis, typically following open coding and preceding selective coding.

- It was developed by Strauss and Corbin as part of grounded theory methodology, though it’s now used more broadly in qualitative research.

- Axial coding involves active analysis and interpretation.

- It involves re-examining and refining the initial codes developed during open coding, connecting them to form categories and subcategories, and developing connections between them.

What is the purpose of axial coding?

Axial coding aims to move beyond simply describing the data to developing a more conceptual understanding.

It involves identifying relationships and connections between codes, grouping them into categories and subcategories, and uncovering the underlying patterns and processes within the data.

This process helps to create a framework for understanding the complex relationships within the data, paving the way for theory development

Axial coding helps to:

- Identify relationships and connections between codes.

- Develop a hierarchical structure of categories and subcategories.

- Uncover the underlying patterns and processes within the data.

Think of it as creating connections along the “axes” of categories – hence the term “axial.”

When does axial coding occur?

Axial coding is a stage in qualitative data analysis that usually happens after open coding.

Open coding is the first step where you read through the data and come up with initial codes.

It is important to remember that qualitative data analysis is an iterative process, and researchers often move back and forth between different stages.

So, even though axial coding generally comes after open coding, you might revisit and adjust your axial codes as you continue to analyze the data and develop your understanding.

How is axial coding done?

Axial coding involves connecting codes to form categories and subcategories and developing connections between them to uncover the underlying patterns and processes within the data.

Axial coding is an iterative and reflexive process.

Don’t hesitate to experiment, revise, and refine your analysis until you arrive at a framework that accurately reflects the complexity and richness of the data and helps to answer the research question.

1. Review your initial codes and categories:

Begin by carefully reviewing the initial codes and categories generated during open coding. Spread out the codes (if on post it notes) and consider what each one represents.

If using qualitative data analysis software, run frequency reports to understand the distribution and prevalence of different codes.

Consider the meaning of each code, its potential significance to the research question, and its relationship to other codes.

2. Look for patterns and relationships:

Examine the codes and memos to identify potential connections and patterns.

Look for codes that frequently appear together, codes that seem to contradict each other, and codes that represent different aspects of the same concept.

Ask questions about the data: why certain codes are more prevalent, what conditions or factors might influence the occurrence of specific codes, and what consequences or outcomes might be associated with them.

3. Group related concepts:

Once you have identified patterns and relationships, start grouping related codes into categories and subcategories.

Consider creating overarching or higher-level categories that encompass several related codes.

For example, if you have codes like “time management,” “procrastination,” and “study habits,” you could group them under a broader category like “academic challenges”.

Grouping similar codes helps to develop a more organized and conceptual understanding of the data.

4. Utilize a Coding Paradigm (Optional)

A coding paradigm is a conceptual framework used in grounded theory, particularly in the Straussian approach, to guide the process of axial coding, where you analyze relationships between codes and categories.

It provides a structured way to examine data and explore connections between different aspects of a phenomenon.

Here’s a breakdown of a typical coding paradigm:

- Phenomenon (central category): The central event, issue, or process you are investigating. What’s actually happening in the data.

- Causal conditions: Factors or events that lead to the phenomenon under study. The “why” behind what’s happening.

- Context: The specific circumstances or setting in which the phenomenon occurs.

- Intervening conditions: Broader structural conditions that influence strategies (often unexpected).

- Action/interaction strategies: Actions or interactions people take in response to the phenomenon.

- Consequences: The outcomes or results of the phenomenon and the strategies employed.

For example, if studying workplace burnout:

- Phenomenon: Employee burnout

- Causal conditions: Heavy workload, tight deadlines

- Context: Competitive industry, economic pressure

- Intervening conditions: Family responsibilities, health issues

- Action strategies: Taking breaks, seeking support

- Consequences: Reduced productivity, staff turnover

The coding paradigm, as advocated by Strauss and Corbin, suggests analyzing data through these specific dimensions to understand the complex interplay of factors surrounding the phenomenon.

However, the use of a coding paradigm in grounded theory is debated.

While some researchers find it helpful for systematically analyzing relationships and developing a structured theory, others, particularly those following the Glaserian approach, argue that it can be too prescriptive and limit the inductive and emergent nature of grounded theory.

They believe that using a pre-determined framework may lead to forcing the data into categories that don’t naturally fit and neglecting potentially important aspects that fall outside the paradigm’s dimensions.

5. Create hierarchical structures:

As you group codes into categories, consider creating a hierarchical structure.

Some categories might naturally fall under others, forming subcategories that offer a more nuanced and detailed understanding.

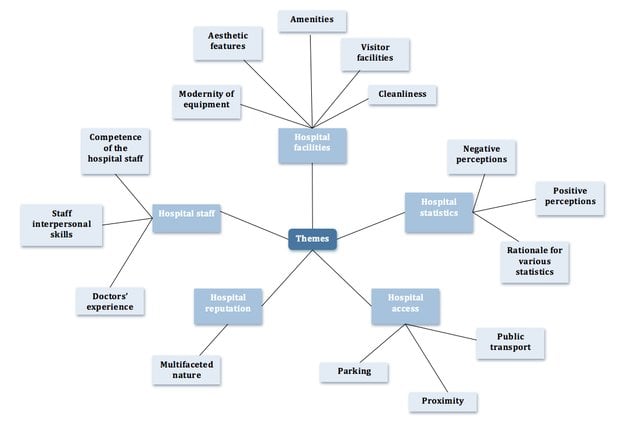

This hierarchical structure, often depicted visually through diagrams or mind maps, helps to represent the relationships between concepts and reveal the complexity of the data.

For example, a mind map can be used to illustrate the relationship between codes and themes related to a strategic alignment model.

6. Document the connections and relationships found:

Throughout the process, it’s crucial to document the connections and relationships you are discovering between codes, categories, and subcategories.

Use memos to record your insights, questions, and analytical decisions.

Describe the nature of the relationships, explain your rationale for grouping codes in particular ways, and provide examples from the data to support your interpretations.

This documentation helps to create an audit trail of your analysis, enhance transparency, and ensure rigor.

Example of axial coding

Here’s an example of axial coding, exploring the experiences of nurses working in intensive care units during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Review Your Initial Codes and Categories

After open coding, the researcher has a detailed codebook. Some of the codes might include:

- Patient care: Describes actions and interactions directly related to patient treatment and well-being.

- Communication: Instances where nurses discuss interacting with patients, families, or colleagues.

- Emotional expressions: Captures the feelings and emotional states conveyed by nurses.

- Decision-making: Highlights moments where nurses describe making critical choices regarding patient care.

- Resources: References to available or lacking equipment, supplies, or personnel support.

- Safety protocols: Mentions of procedures and guidelines related to infection control and personal protection.

2. Look for Patterns and Relationships

The researcher begins to notice connections between these initial codes:

- Emotional expressions often arise when nurses discuss patient care, particularly in situations involving difficult decisions or limited resources.

- Instances of communication frequently relate to concerns about safety protocols, indicating anxieties about personal risk and potential virus transmission.

- Decision-making appears closely linked to resources, with nurses expressing frustration and moral distress when forced to prioritize care due to shortages.

3. Group Related Concepts

Based on these patterns, the researcher starts grouping related codes:

- Theme 1: Ethical Challenges: This theme emerges from the interplay of patient care, emotional expressions, decision-making, and resources. It reflects the moral dilemmas and emotional burdens nurses experience when trying to provide optimal care under constrained circumstances.

- Theme 2: Communication and Safety: This theme connects communication and safety protocols. It highlights the importance of clear communication and adherence to safety guidelines for mitigating anxiety and ensuring a safe working environment.

4. Create Hierarchical Structures

The researcher might create a hierarchical structure to represent these relationships:

Overarching Theme: Navigating the Pandemic

- Subtheme: Ethical Challenges

- Patient care

- Emotional expressions

- Decision-making

- Resources

- Subtheme: Communication and Safety

- Communication

- Safety protocols

This structure shows the connection between the subthemes under the larger context of how nurses are managing their experiences during the pandemic.

5. Document the Connections and Relationships Found

Throughout axial coding, the researcher meticulously documents their observations and the reasoning behind their decisions. They might write analytical memos explaining:

- How specific codes relate to each other.

- The rationale for grouping certain codes into themes.

- Emerging insights about the relationships between themes.

- Potential areas for further exploration.

This documentation creates a transparent audit trail that demonstrates the rigor and thoughtfulness of the analytical process.

This detailed record of the researcher’s analytical journey enhances the trustworthiness of the findings.

challenges of axial coding

Axial coding is a crucial stage in qualitative data analysis, where researchers delve deeper into the initial codes from open coding to uncover relationships and build a more conceptual understanding of the data.

However, it can also present several challenges. Some of the common challenges researchers face during axial coding include:

- Difficulty identifying meaningful connections: It can be challenging to discern meaningful relationships between codes, especially with large and complex datasets. Codes may appear together but not necessarily indicate a substantial relationship.

Researchers must carefully consider the context and nuances of the data to determine the true nature of connections. - Bias and subjectivity: Axial coding involves interpretation and judgment, making it susceptible to researcher bias and subjectivity.

Researchers’ pre-existing beliefs, assumptions, and theoretical perspectives can unconsciously influence how they categorize and interpret the data. - Lack of clear guidance: Axial coding lacks a standardized or universally accepted procedure. It is a flexible process that can vary considerably depending on the researcher, the research question, and the data itself.

This lack of clear guidance can make it difficult for novice researchers to know where to start, how to proceed, and when they have reached a satisfactory level of analysis. - Dealing with disconfirming voices: When conducting a member check, a process where researchers share their findings with participants to verify accuracy and interpretation, there is a risk of encountering challenges or disagreements.

This can be difficult to navigate, especially if participants contest the researcher’s analysis. - Managing complexity: As researchers group codes into categories, create hierarchical structures, and develop connections, the analysis can become increasingly complex.

It can be challenging to keep track of all the different elements, their relationships, and their significance.

Researchers need to develop robust organizational strategies, such as using diagrams, mind maps, or software tools, to manage the complexity and ensure that the analysis remains coherent and transparent. - Time and resource constraints: Axial coding requires researchers to dedicate significant effort to immersing themselves in the data, carefully examining the codes, identifying patterns, and developing connections.

This can be challenging for researchers working under tight deadlines or with limited resources.

tips for effective axial coding

- Stay focused on the research question: The categories and connections you develop should align with your research goals.

- Engage in regular memo writing: Memos can help you capture insights, explore connections, and track your analytical decisions.

- Seek feedback from colleagues or peers: Discussing your coding with others can help you identify blind spots and refine your analysis.

- Be mindful of saturation: Consider whether additional data collection is needed to reach data saturation, the point at which no new codes or themes are emerging. This ensures that the analysis is comprehensive and captures the full range of perspectives and experiences within the data.

- Be reflexive. Consider how your own experiences and assumptions might be shaping your interpretations.

- Use thick descriptions: Provide thick and thick descriptions using robust descriptive language to convey sufficient contextual information to the reader. This enhances the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the findings.

- Use software tools: Qualitative data analysis software (QDAS) like NVivo or ATLAS.ti can facilitate the coding and organizing of data. However, it’s important to note that software tools should support, not replace, the researcher’s analytical thinking.

By effectively engaging in axial coding, researchers can move beyond descriptive summaries to develop richer, more nuanced, and theoretically grounded interpretations of their data.

Reading List

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Kendall, J. (1999). Axial coding and the grounded theory controversy. Western journal of nursing research, 21(6), 743-757.

- Scott, C., & Medaugh, M. (2017). Axial coding. The international encyclopedia of communication research methods, 10, 9781118901731.

- Vollstedt, M., & Rezat, S. (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education, 13(1), 81-100.