Think of a psychology essay as a scientific argument rather than a creative story. It is about using empirical evidence, like scientific studies and data, to evaluate theories or answer a specific question about behavior. Your goal is to remain objective, follow specific formatting rules like APA style, and critically analyze the strengths and limitations of the research you cite.

Key Characteristics

- Global Structure: Structure the essay to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”.

- Scientific and Factual Focus: Psychology writing aims to inform the reader about ideas, theories, or experiments, conveying factual knowledge backed by research.

- Critical Evaluation: Arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Clear and Concise: Minimize descriptive language and complex sentence structures. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences. Complex ideas must be made understandable.

- Use of Evidence: Conclusions must rely on high quality evidence rather than personal opinions or direct quotations.

- Primary Sources: Rely primarily on original empirical papers found in peer-reviewed journals, as opposed to secondary reports or summaries.

- Citing Sources: Psychologists rarely use direct quotations; instead, they distill the essence of an idea or finding and cite the source. The reference style mandated for psychology papers is typically APA style (American Psychological Association).

Reading and planning will make the essay writing process easier, quicker, and ensure a higher quality essay is produced.

DON’t skip this step!!

A common pitfall is viewing planning merely as compiling a list of theories of studies (reproduction of knowledge).

Instead, you must plan how you will link evidence together to construct a coherent argument (academic discourse).

The hardest part of an essay isn’t usually writing the sentences, it’s figuring out what the research actually says and how to build an argument from it without getting lost in dense academic language.

NotebookLM is uniquely suited for this because it grounds its answers in the specific PDFs (journal articles) you upload, rather than hallucinating random facts from the internet.

Phase 1: The “Evidence Dump” (Setup)

Don’t read your articles one by one yet.

First, create a “Notebook” for your essay topic and upload all your PDF sources (journal articles, lecture notes, textbook chapters) into it.

Why this helps:

You now have a “closed system.”

You can ask questions, and the AI will answer only using the material you have to cite, giving you little citations [1] you can click to verify.

Phase 2: Interrogate the Evidence (Understanding)

Freshman psychology essays often fail because students describe what a study found, but not how good the study was (the evidence quality).

For example, there may be more evidence to support they X, but if the evidence quality if higher for theory Z, it would make sense to struture your essay to argue for this position.

To pick your argument, look for:

- Where the evidence clusters (most studies point in one direction)

- Which findings are most robust (e.g., replicated, large samples)

- Which argument you can support with clear examples

Your argument doesn’t need to be dramatic — it just needs to be evidence-based and defensible.

1. The “WEIRD” Check (Demographics)

Psychology often relies too much on Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic participants (like US college students).

Prompt: “Analyze the demographic data of the participants in these sources. Are they diverse, or are they mostly ‘WEIRD’ populations? Does this limit the external validity of their findings?”

2. The Methodology Audit

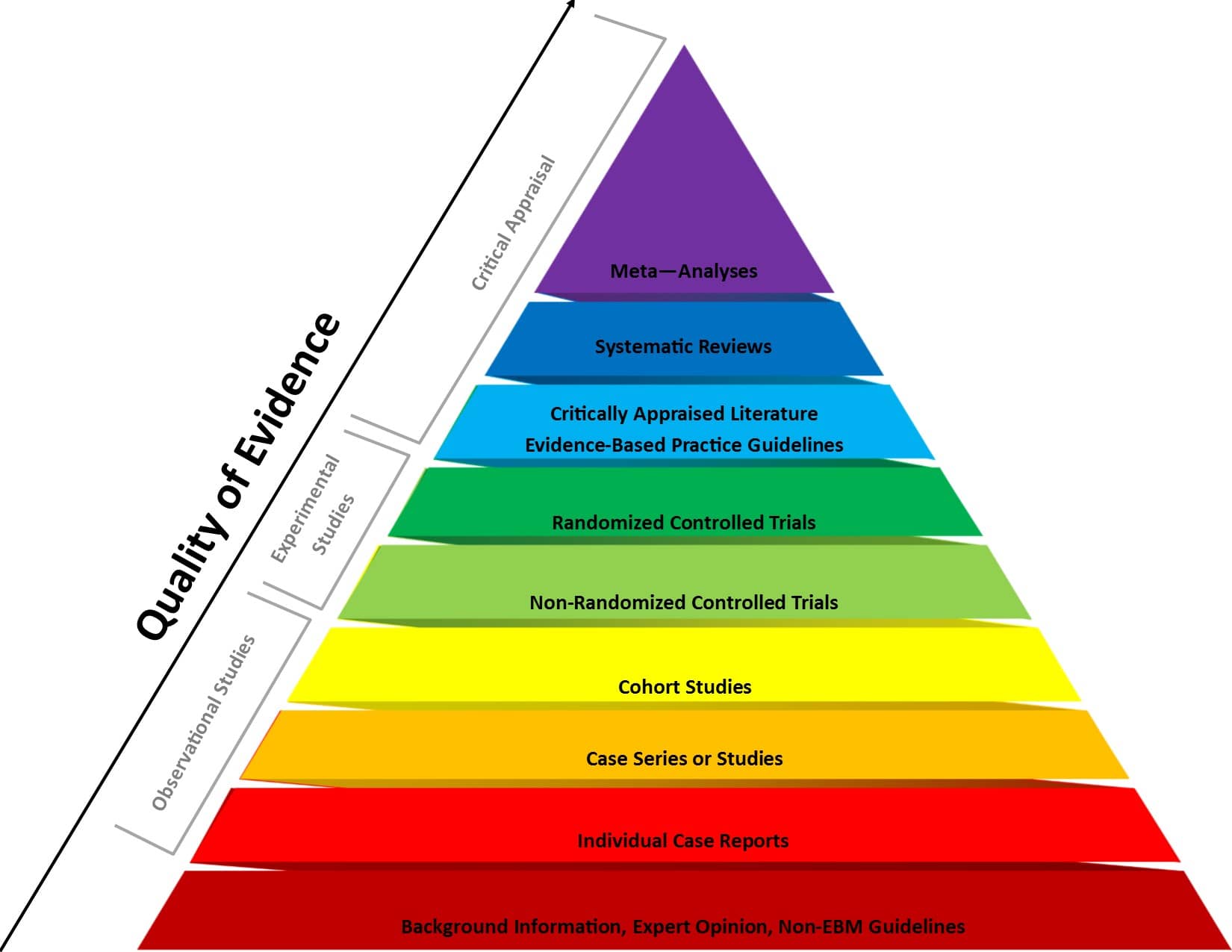

Prompt: “Identify the competing arguments regarding [Topic]. Create a table comparing them by Quantity (count of sources) and Quality (study type). Grade the quality using the Hierarchy of Evidence: Tier 1 (Meta-Analyses/Systematic Reviews), Tier 2 (RCTs), Tier 3 (Observational), Tier 4 (Opinion). Which argument has the strongest scientific backing?”

Quality Trumps Quantity

-

Scenario: Argument A has 10 sources, but they are all “Tier 4” (Expert Opinion/Case Reports). Argument B has 2 sources, but they are “Tier 1” (Meta-Analyses).

-

Your Essay Argument: You should argue for Argument B. Even though it has less quantity, the quality of evidence is scientifically superior according to the pyramid.

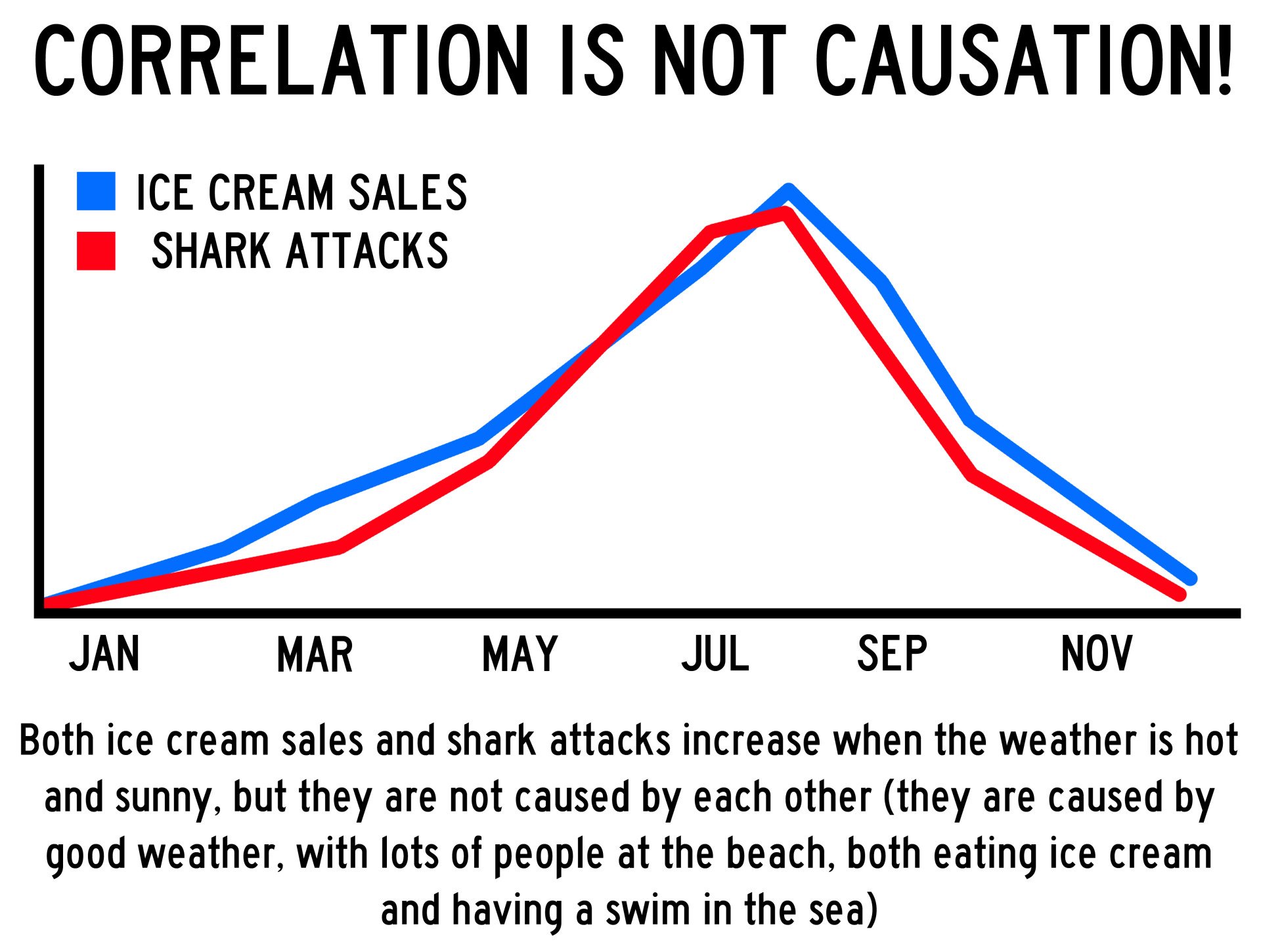

If NotebookLM tells you that the opposing view is mostly supported by Observational Studies (Tier 3), you can critique that in your essay:

“While proponents of Theory X cite numerous studies, these rely primarily on observational data, which cannot establish causality as effectively as the Randomized Controlled Trials supporting Theory Y.”

The “Mixed Bag”

If you find a mix (e.g., strong RCTs for short-term effects, but only Case Studies for long-term effects), that is your thesis:

“The intervention is proven effective in the short term (Tier 1 evidence), but its long-term viability remains unproven due to a lack of high-quality longitudinal data.”

3. The “Correlation vs. Causation” Trap

Prompt: “Do any of these authors make causal claims based on correlational data? Identify where the evidence might be overstating the results.”

If a results section is full of p-values and complex statisticss you don’t understand:

Prompt: “Explain the ‘Results’ section of the Johnson et al. (2023) paper in simple terms for a broad audience. What was the statistical significance of their main finding?”

Phase 3: Find the Tension (Deciding What to Argue)

An A-grade essay doesn’t just list facts; it makes an argument. You need to find where your sources disagree or where there is a gap.

1. The “Audio Overview” Hack (Listen to the Debate)

This is NotebookLM’s “killer feature.” Click Audio Overview -> Generate.

-

What it does: It turns your dry PDFs into an engaging, podcast-style conversation between two AI hosts.

-

How to use it: Listen to it while walking to class. The hosts will naturally try to connect the dots between your sources. If they say, “It’s interesting that Source A says X, but Source B contradicts that with Y…” Stop. That is your essay topic. You will argue for one side or explain why the contradiction exists.

2. The “Synthesis” Prompts

Use these prompts to force the AI to find the argument for you:

-

The Conflict Finder: *”Identify the three biggest disagreements or contradictions between these evidence regarding [Topic].”

-

The Gap Finder: “What is a question that none of these researchers seem to answer satisfactorily? Where is the gap in this evidence?”

-

The Thesis Generator: “Based on the limitations you found in these studies, propose 3 provocative thesis statements I could argue for this essay.”

Phase 4: Construct the Skeleton

Once you have decided on your argument (e.g., “While early research suggested X, new evidence implies Y because of Z methodology”), use NotebookLM to build your outline.

Prompt: “Create an outline for an argumentative essay supporting the thesis: ‘[Your Thesis]’. For each body paragraph, provide 2 bullet points of evidence from my sources that support that claim, including the citation numbers.”

Essay Structure

Don’t fall into the trap of writing everything you know about a topic.

Be selective.

Every paragraph in your essay should move you closer to answering the question — if it doesn’t help your argument, leave it out.

Before you start writing, decide on a clear position or thesis statement (this is why planning is essential).

This is the overall argument your essay will make. Your thesis acts as a guide: it tells you what evidence to include and helps your essay flow logically.

Make sure your introduction, main body, and conclusion all connect back to this central argument. They should feel like parts of the same conversation.

Choose the strongest, most persuasive reasons that support your position.

Select evidence for each reason, group related ideas together, and organise your points in a logical order — usually with your most convincing point first.

Finally, include counter-arguments.

Showing the opposing view proves you can think critically. Explain why these counter-arguments are less convincing and how your position still stands overall.

Introduction (The Beginning)

The introduction is the gateway to your argument and should generally be about 10% of the word count.

Introductions are very important as first impressions count and they can create a halo effect in the mind of the lecturer grading your essay.

- Thesis Statement/Position: State your clear position or overall argument on the essay topic. This is the most crucial part, as all other parts of the essay support it. This should be presented early, do not wait until the conclusion.

- Signposting: Explicitly outline the main points and the order in which they will be covered in the body of the essay. This tells the reader exactly how you will arrive at your conclusion.

- Context/Background: Provide necessary background information, definitions of key concepts, and a brief history or current context of the topic. Define key concepts concisely.

Main Body (The Middle)

The main body is where you present arguments, knowledge, evidence, and critical evaluation, developing the specific points outlined in the introduction.

There should also be an appropriate balance between knowledge and critical evaluation. Try to aim for about a 60/40 split if possible.

- Global Structure: Structure the material to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”.

- Paragraph Structure: Dedicate each paragraph to one main theme (idea), which is illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence). Avoid cataloguing unconnected points. Use the Point-Evidence-Explanation (PEE) model:

- Topic Sentence: States the central idea or point of the paragraph, linking back to the overall argument.

- Support/Development: Provide evidence, examples, data, and explanations (from multiple sources if necessary) to support the topic sentence. Psychology essays typically use the fact:citation sentence pattern (a paraphrased fact followed by the citation).

- Critical Analysis/Evaluation: Critically analyse the evidence (methodology, biases, generalizability). This shows awareness of complexity.

- Concluding Sentence: Summarise the paragraph’s idea and link it back to the essay question or transition to the next point.

- Synthesis and Refutation: Evidence should be synthesised (comparing and contrasting multiple sources on the same concept) to show nuanced understanding and breadth of reading.

- Avoid Quotes: Try not to overuse quotations in your essays. It is more appropriate to use original content to demonstrate your understanding.

- Citations: As a general rule, make sure there is at least one citation (i.e. name of psychologist and date of publication) in each paragraph.

- Critical Evaluation: Evaluation separates high-quality work from merely descriptive writing. High-quality essays must also include counter-arguments and refute them by demonstrating their weaknesses to strengthen the main argument.

-

- Critical evaluation should be coherent and relevant, linking studies together and clarifying their value in answering the question.

- For the highest marks, acknowledge theoretical and methodological challenges inherent in the research field, highlighting crucial controls and well-explained limitations.

- Avoid merely highlighting weaknesses; suggest improvements or explain why the limitations do not detract from your argument.

- Scholarly Style: Write in the third person to convey objectivity (e.g., “It has been shown that…”). Define technical terms and acronyms when first introduced. Provide a balanced view of the topic, discussing pros and cons.

Conclusion (Implications)

So many students either forget to write a conclusion or fail to give it the attention it deserves.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your conclusion.

The conclusion summarises and evaluates the material presented, linking it back to the thesis statement and discussing the implications of the findings.

Also, you might like to suggest what future research may need to be conducted and why (read the discussion section of journal articles for this).

If you are unsure of what to write read the essay question and answer it in one paragraph.

Points that unite or embrace several themes can be used to great effect as part of your conclusion.

- Restate Position: Briefly restate your thesis or position. Don’t sit on the fence, instead weigh up the evidence presented in the essay and make a decision which side of the argument has more support.

- Summarise Main Points: Summarise the main arguments and evidence presented in the body. In scientific essays, this is often coupled with a critical analysis of the evidence and sources.

- Implications: Clarify the significance of your findings, suggest implications for the broader field, or recommend specific future research by suggesting appropriate methods or questions. Avoid generic statements like “more research is needed”.

- New Information: Do not include new material or citations in the conclusion.

Post-Writing and Avoiding Misconduct

- Proofreading: Always proofread for spelling and grammatical errors. Reading your essay again after a few days can help you spot errors and assess logical flow.

- Plagiarism: Plagiarism is presenting someone else’s words, work, or ideas as your own, whether deliberately or accidentally, and penalties are severe.

- Avoidance: Write notes in your own words, never cut and paste from the internet, and ensure proper citation using APA style.

- Collusion: Never lend your completed essay to another student, as both students can be punished if plagiarism is discovered.

- Detection: Plagiarism is easily detected by experienced markers and electronic software which compares submissions against the internet and other student work.

- Final Submission: Keep a copy of your essay (electronic or photocopy) for revision and as a backup. Ensure your name/candidate number and course are clearly marked on all pages.

Now, let us look at what constitutes a good essay in psychology. There are a number of important features.

- Knowledge and Understanding – recognize, recall, and show understanding of a range of scientific material that accurately reflects the main theoretical perspectives.

- Critical Evaluation – arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Quality of Written Communication – writing clearly and succinctly with appropriate use of paragraphs, spelling, and grammar. All sources are referenced accurately and in line with APA guidelines.

Most students make the mistake of writing too much knowledge and not enough evaluation (which is the difficult bit).

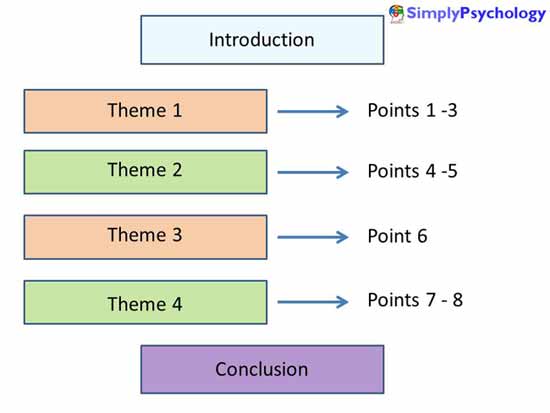

It is best to structure your essay according to key themes. Themes are illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

Choose relevant points only, ones that most reveal the theme or help to make a convincing and interesting argument.

The Point-Evidence-Explanation (PEE) model is a strategic framework recommended for structuring the main body paragraphs of an academic essay, particularly in psychology, to ensure clarity, logical flow, and rigorous support for arguments. This structure helps transform an essay from a mere catalogue of ideas into a cohesive, well-supported academic discourse.

In a comprehensive response to an essay question, each main body paragraph should dedicate itself to one specific idea or point, which is then developed using the PEE model.

PEE Model

By applying PEE, students are forced to think about how they intend to use and link the information, rather than just compiling an “inventory of content”.

The PEE model instructs writers to structure their paragraphs using three core components:

1. Point (The Topic Sentence)

This sentence introduces the central idea or argument of the paragraph, which must align with the overall thesis or contention of the essay.

- Function: The topic sentence states the main idea and ensures the paragraph is focused. It should clearly link the paragraph’s content back to the overall thesis statement (or overall argument) of the essay.

- Signposting: Good scientific essays often use the point to signpost (or explicitly tell the reader) what the paragraph is about. For example, a sentence summarizing the paragraph’s argument, to quickly convey complex information to the marker.

2. Evidence (The Support)

This section develops the point by presenting factual support, empirical data, examples, or theoretical descriptions from sources to substantiate the claim.

In academic writing, particularly science-based essays, multiple sources should be used per paragraph.

- Content: This section must provide factual support, usually in the form of empirical findings, data, examples, quotes, or theoretical descriptions from scholarly sources.

- Scholarly Approach: In scientific essays, specifically in psychology, conclusions must rely on data or empirical demonstrations, not just personal opinions or direct quotations. Psychologists prefer writers to distil the essence of findings and cite the source, rather than using direct quotes. A common, effective method is the fact:citation sentence pattern, where a paraphrased fact is immediately followed by the citation.

- Synthesis: Ideally, you should synthesise material by referring to multiple relevant sources in a single paragraph to demonstrate breadth of reading and nuance in understanding.

For instance, one might state an apparent finding (the Point) and then explain why, despite the supporting evidence, the lack of randomization in the study limits the conclusions that can be drawn (the Explanation).

3. Explanation (The Critical Analysis and Link)

This step involves explaining the implications of the evidence, critiquing the methodology, or introducing counter-arguments and refuting them.

Thus, demonstrating critical analysis and ensuring the argument is coherent and returns to the central thesis

- Elaboration and Justification: This part requires you to make clear how the evidence supports your point and why it is relevant to the essay question. In critical analysis, this involves weighing arguments for and against a claim and assessing the strength of the evidence.

- Critical Evaluation: Critical evaluation is essential for high marks and should be integrated within the body paragraphs, rather than simply listed at the end of the essay. Critical analysis involves constructively commenting on the study design, methodological limitations, and biases, and can involve suggesting improvements or explaining why the limitations do not detract from the overall argument.

- Concluding Sentence: The explanation typically ends with a sentence that summarises the paragraph’s idea and effectively links it back to the overall essay question or transitions to the next paragraph.

PEE as an Argumentative Tool in Psychology

The PEE model is intrinsically linked to writing a scholarly, argumentative essay rather than a purely descriptive one.

When essay planning, students should avoid merely listing content topics (reproduction of knowledge) and focus instead on designing the argument (academic discourse).

The PEE structure forces the writer to move beyond simply reporting facts towards constructing a reasoned analysis.

High-quality arguments require the point (or idea) to be central and supported by adequate, critically examined data.

For example, planning often involves determining the persuasive reasons for a thesis, selecting evidence for them, grouping related arguments, and ordering them logically (with the strongest points first). Each paragraph, following the PEE structure, delivers a clear step in that overall logical sequence.

Critical Evaluation

Critical evaluation distinguishes high-quality essays from merely descriptive work, requiring in-depth analysis and the reasoned scrutiny of evidence.

Critical evaluation involves evaluating theories, information, or situations, posing questions, and challenging existing information.

Effective critical evaluation must be integrated throughout the essay rather than being confined to a single section.

There are many ways you can critically evaluate:

Originality and Insight

Originality refers to producing work that is fresh or novel, such as presenting a study the marker has not read or taught, or suggesting a new approach.

However, this does not mean inventing a groundbreaking theory; rather, it means developing a good, well-researched argument that incorporates insightful interpretations.

Insight involves an authoritative understanding that allows the student to move beyond basic concepts and consider complexities.

It demonstrates an appreciation of major points and the ability to integrate material that goes beyond the core course material.

Originality and insight are achieved by integrating critical analysis, broader reading, and informed speculation into the essay’s fabric.

1. Critically Linking and Interpreting Evidence

A primary way to demonstrate originality is through sophisticated critical evaluation and linking of material:

- Critically Linking Studies: Rather than merely discussing each piece of evidence separately, a First class essay critically links studies together to form a coherent argument.

- Developing New Interpretations: Insight can be shown through an interpretation and/or alternative explanation of existing evidence that the marker may not have previously considered.

- Highlighting Gaps: Showing originality involves attacking the core question and questioning whether the stated goal is even achievable (e.g., questioning whether symptoms can be explained by a single theory).

2. Strategic Use of Reading and Sources

Going beyond the obvious or prescribed materials enhances insight and demonstrates a deeper engagement with the academic field:

- Broad-based Reading: Achieving a First class mark requires evidence of extra reading. This means incorporating a broader range of material.

- Identifying Current Trends: You can convey the impression of extensive and contemporary reading by finding recent articles (e.g., in the last five years).

- Accessing Primary Sources: Relying on original empirical papers (rather than secondary summaries) and clearly demonstrating how they relate to the argument shows scholarly rigour.

Synthesising Evidence

In the main body of an essay, synthesising sources is essential for developing a strong argument in each paragraph.

Synthesising evidence involves gathering and integrating multiple sources to support an argument, establish a balanced perspective, or highlight nuances in research findings, rather than merely listing individual study results.

For instance, when addressing a complex topic, you might find two researchers (Elphick and Mitchell) who both argue that fabrication is a critical facet of psychotic behaviour, viewing it as a conscious process.

You would synthesise this by stating that both authors hold this viewpoint, thus strengthening the evidence for the argument being made in that paragraph.

Core Functions of Synthesising Evidence

- Supporting an Argument: Synthesis allows you to substantiate your points by demonstrating that multiple people share the same view on a topic or claim. This is central to writing a Point-Evidence-Explanation (PEE) paragraph, where evidence (often from multiple sources) is used to develop and support the main idea of the paragraph.

- Demonstrating Breadth of Reading: Integrating diverse sources shows the reader that you have read widely and deeply across the relevant literature.

- Achieving Balance and Nuance: By comparing and contrasting different perspectives, synthesis helps you present a balanced, non-biased argument. This can highlight subtle differences (nuances) between different schools of thought or demonstrate how sources agree or differ on specific concepts.

- Moving Beyond Description: Synthesis is a hallmark of critical thinking. Instead of writing separate paragraphs dedicated to separate readings (“Paragraph 1: source 1 says this…., Paragraph 2: source 2 says this….”), combining sources around a central concept maintains argumentative flow and cohesion.

Point-Evidence-Explanation (PEE)

Within the framework of the main body, the “Explanation” phase is where the evidence supporting a point is constructively commented on, assessed for its strength, and linked back to the overall argument.

Implications and Future Research

A strong concluding statement should clarify the significance of your arguments and suggest specific future research directions, highlighting the remaining uncertainties.

It is not enough simply to state that “more research is needed”; you must be specific about appropriate methods or questions.

Methodological evaluation of research

- Is the study valid / reliable?

- Is the sample biased, or can we generalize the findings to other populations?

- What are the strengths and limitations of the method used and data obtained?

Critique involves analyzing evidence by addressing the methodological challenges inherent in the research field.

You should comment constructively on the level of evidence (e.g., whether it is a meta-analysis or a case study), the study design, confounding factors, and biases involved.

Be careful to ensure that any methodological criticisms are justified and not trite.

Rather than hunting for weaknesses in every study; only highlight limitations that make you doubt the conclusions that the authors have drawn.

For example, where an alternative explanation might be equally likely because something hasn’t been adequately controlled.

Counter-Arguments and Refutation

To demonstrate critical thinking, you must include counter-arguments or alternative perspectives.

This involves not just mentioning opposing views, but thoroughly demonstrating the weaknesses or refuting why they do not sway your overall position.

Compare or contrast different theories

Outline how the theories are similar and how they differ.

This could be two (or more) theories of personality / memory / child development etc.

Also try to communicate the value and implications of the theory / study.

Debates or perspectives

Refer to debates such as nature or nurture, reductionism vs. holism, or the perspectives in psychology.

For example, would they agree or disagree with a theory or the findings of the study?

What are the ethical issues of the research?

Does a study involve ethical issues such as deception, privacy, psychological or physical harm?

Gender bias

If research is biased towards men or women it does not provide a clear view of the behavior that has been studied. A dominantly male perspective is known as an androcentric bias.

Cultural bias

Is the theory / study ethnocentric? Psychology is predominantly a white, Euro-American enterprise. In some texts, over 90% of studies have US participants, who are predominantly white and middle class.

Does the theory or study being discussed judge other cultures by Western standards?

Animal Research

This raises the issue of whether it’s morally and/or scientifically right to use animals. The main criterion is that benefits must outweigh costs. But benefits are almost always to humans and costs to animals.

Animal research also raises the issue of extrapolation. Can we generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy & physiology is different from humans?

Using Research Studies in your Essays

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation.

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies shows, and what it supports and challenges about the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Importance of Flow

Obviously, what you write is important, but how you communicate your ideas / arguments has a significant influence on your overall grade.

Most students may have similar information / content in their essays, but the better students communicate this information concisely and articulately.

When you have finished the first draft of your essay you must check if it “flows”. This is an important feature of quality of communication (along with spelling and grammar).

This means that the paragraphs follow a logical order (like the chapters in a novel). Have a global structure with themes arranged in a way that allows for a logical sequence of ideas.

Good essay writing avoids presenting material as a sequence of disparate or unconnected points, instead weaving them into a structured narrative that leads coherently to a conclusion.

You might want to rearrange (cut and paste) paragraphs to a different position in your essay if they don”t appear to fit in with the essay structure.

To improve the flow of your essay make sure the last sentence of one paragraph links to first sentence of the next paragraph. This will help the essay flow and make it easier to read.

Finally, only repeat citations when it is unclear which study / theory you are discussing. Repeating citations unnecessarily disrupts the flow of an essay.

Avoiding Disruption to Flow

Poor organisation or lack of structural coherence disrupts the flow and makes the writing difficult to follow:

- Disorganised Material: If the material is organised randomly, or if the overall structure is unclear, the essay may suffer from “muddy” organisation in places.

- Lack of Synthesis: Flow is damaged if the essay merely lists sources individually (e.g., “Paragraph 1: source 1 says this…., Paragraph 2: source 2 says this….”) rather than synthesising them around a central concept (theme).

- Unclear Argumentation: An essay that seems to be “a series of disparate paragraphs that have just been kind of thrown on the page” lacks continuity and narrative flow.

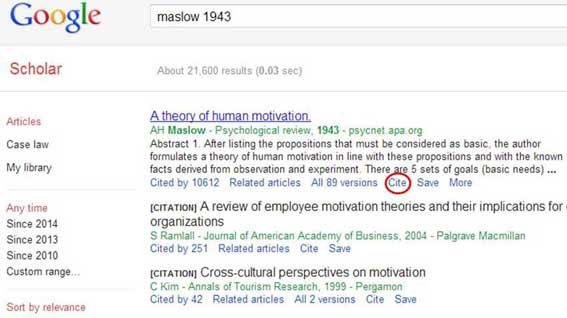

Referencing

The reference section is the list of all the sources cited in the essay (in alphabetical order). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms every time you cite/refer to a name (and date) of a psychologist you need to reference the original source of the information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down.

If you have been using websites, then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

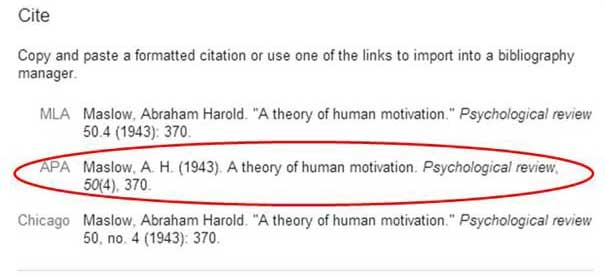

References need to be set out APA style:

Books

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work. Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

A simple way to write your reference section is use Google scholar. Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.