Stockholm Syndrome is a psychological phenomenon where captives develop positive feelings towards their captors. It’s primarily associated with hostage situations and kidnappings, though it can occur in various abusive contexts.

In some instances, the victims form bonds with their captors and may even become sympathetic towards them, the opposite of feeling fear, terror, and disdain, which one may expect in these situations.

The term originated from a 1973 bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden. During a six-day standoff, four hostages formed emotional bonds with their captors, even defending them after release.

Criminologist Nils Bejerot coined the term “Stockholm Syndrome” to describe this unexpected response.

Key aspects of Stockholm Syndrome include:

- It’s considered a survival mechanism in life-threatening situations.

- Development can occur over days, weeks, or even years of captivity or abuse.

- It’s relatively rare, with the FBI estimating it affects less than 8% of kidnapping victims.

- It’s not recognized as a mental disorder in the DSM-5.

- Some researchers debate its existence as a distinct condition.

Interestingly, the syndrome doesn’t occur in all captive situations, and its exact causes remain unclear. Some experts view it as an aspect of emotional abuse or trauma bonding rather than a standalone syndrome.

This complexity highlights the intricate nature of human psychological responses to extreme situations.

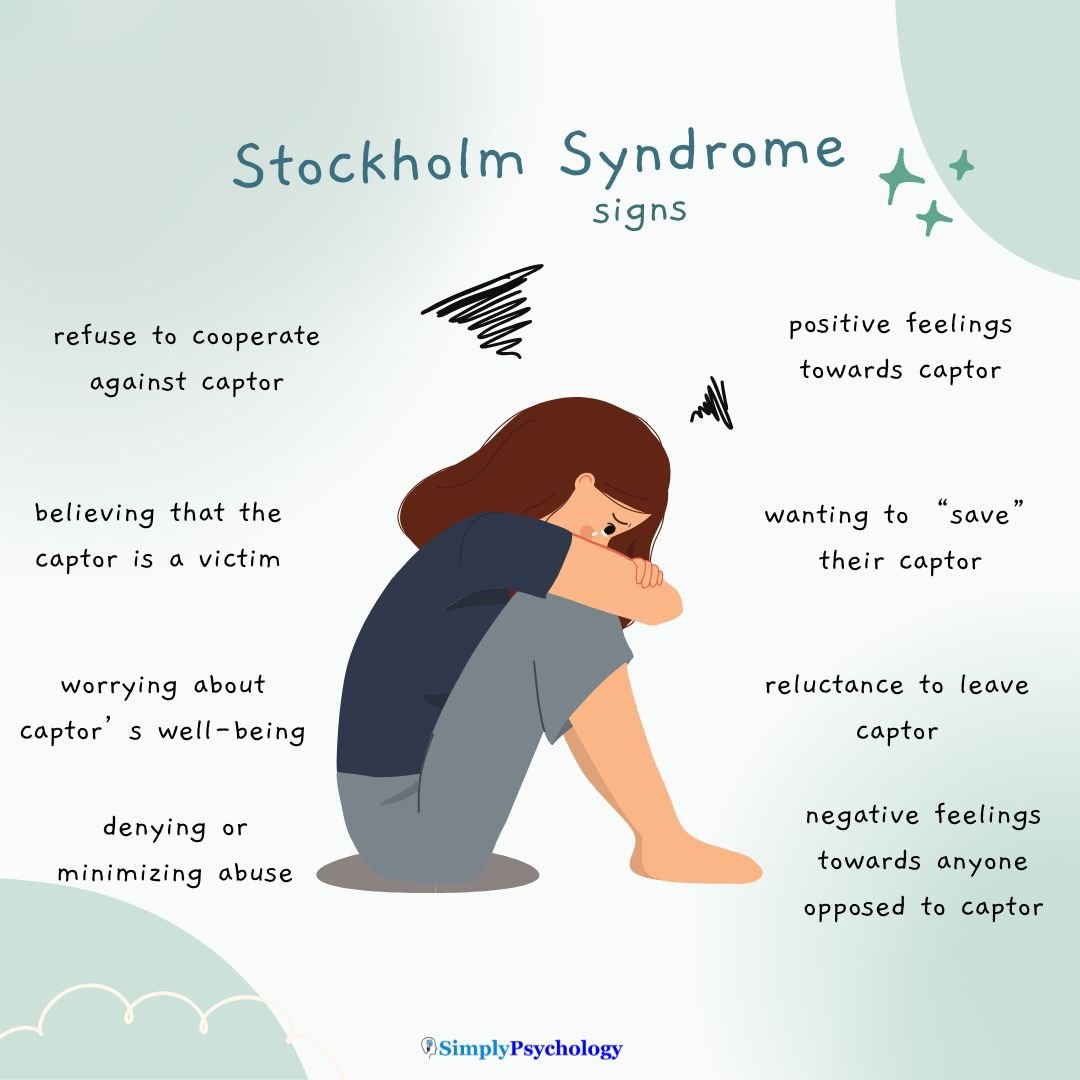

Signs someone is experiencing Stockholm Syndrome

Although Stockholm Syndrome is not listed as a formal mental health diagnosis, people who experience this syndrome tend to display the following signs:

- Positive feelings towards the captor.

- Support of the captor’s behavior and the reasoning behind it.

- Perceiving their captor’s humanity and believing they share the same goals and values.

- They make little to no effort to escape.

- A belief in the goodness of the captors.

- As the victims get rewarded, perhaps with less abuse or with life itself, the captor’s appeasing behaviors are reinforced.

- Feelings of pity towards the captors, even believing that the captors are the victims themselves.

- They may have feelings of wanting to ‘save’ their captor.

Aside from having an attachment or bond with their captor, the victims may also develop different feelings towards outsiders the situation. For instance, they may:

- Be unwilling to engage in any behaviors that could assist in their release.

- Have negative feelings towards their friends or family who may try to rescue them.

- Develop negative feelings towards the police, authority figures, or anyone who might be trying to help them get away from their captor.

- Refuse to cooperate against their captor, such as during the subsequent investigation or during legal trials.

- Refuse to leave their captors even when given the opportunity to escape.

- Believe that the police and other authorities do not have their best interests at heart.

Even after being released from captivity, the person with Stockholm Syndrome may continue to have positive feelings towards their captor and may report some of the following symptoms:

- Continuously thinking positively about their captor, recalling the captor’s actions as protective or caring despite the reality.

- Feeling personally guilty for actions that led to their capture or believing they deserved the treatment they received.

- Denying or minimizing the captor’s abusive behavior, even when faced with clear evidence.

- Withdrawing socially from friends and family, preferring isolation or minimal interaction.

- Frequently experiencing heightened stress and tension, especially when reminded of their captivity.

- Persistent anxiety directly related to their captor, such as worry about the captor’s well-being or fearing harm might come to them.

In addition, individuals often show symptoms similar to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), including:

- Becoming startled easily by unexpected sounds or movements.

- Experiencing persistent mistrust or suspicion towards others.

- Having feelings of unreality, detachment, or dissociation from their surroundings.

- Frequent, intrusive flashbacks vividly reliving aspects of their captivity.

- Heightened irritability, sometimes manifesting as uncharacteristic anger or frustration.

- Recurrent nightmares involving scenarios related to captivity or their captor.

- Difficulty concentrating on daily tasks, showing impaired memory or decision-making.

- Chronic insomnia or severely disrupted sleep patterns.

While not everyone who experiences Stockholm Syndrome will show all these signs, individuals may display varying combinations and intensities of these symptoms. Additionally, because the concept of Stockholm Syndrome itself remains debated, interpretations and experiences may differ widely.

Causes of Stockholm Syndrome

Stockholm Syndrome does not have a single, definitive cause but rather arises from a combination of factors in situations of captivity or prolonged abuse. Below are key contributing factors:

Survival Mechanism

Stockholm Syndrome is primarily considered a psychological strategy for survival. Victims develop positive feelings toward their captors as a coping mechanism to manage overwhelming stress and anxiety experienced during captivity or abuse.

Emotional and Physical Dependence

Victims who rely heavily on their captors for basic needs—such as food, shelter, safety, or even human contact—may begin to feel emotionally dependent.

This dependency can lead victims to perceive their captors positively or sympathetically as providers, rather than solely as threats.

Captor’s Behavior

The captor’s behavior significantly influences the development of Stockholm Syndrome. Occasional acts of kindness, compassion, or simply refraining from violence can trigger emotional bonds, making victims view their captors as benevolent or misunderstood.

Duration and Isolation

Prolonged exposure and isolation from the outside world intensify emotional responses. When victims share confined spaces with captors over extended periods, the continuous, close interaction can blur boundaries, fostering complex emotional connections.

Psychological Complexity and Trauma Bonding

Stockholm Syndrome shares similarities with trauma bonding, where alternating cycles of abuse and kindness create emotional confusion.

Victims remain hopeful for kindness amidst cruelty, reinforcing their emotional attachment and complicating efforts to escape or resist.

Examples

There have been a few famous historical cases that researchers have believed were examples of someone having Stockholm Syndrome.

These examples appear to show that these individuals may have had some level of positive feelings toward their captors. Whether these are actually examples of Stockholm Syndrome is up for debate.

Mary McElroy

In 1933, four men held 25-year-old Mary McElroy at gunpoint, chained her to walls in an abandoned farmhouse, and demanded a ransom from her family.

When she was released, she had reportedly struggled to name her captors in their trial and had publicly expressed sympathy for them. whilst she agreed that her captors should receive punishment, she still visited them whilst they were in prison.

Patty Hearst

One of the most famous examples of what was believed to be Stockholm Syndrome, Hearst, was kidnapped in 1974 by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA).

During her captivity, Hearst was reported to have renounced her family, adopted a new name, and even joined her captors in robbing banks.

She was later arrested and claimed she had Stockholm Syndrome as a defense in her trial.

Natascha Kampusch

In 1998, when ten years old at the time, Kampusch was kidnapped and kept captive in an underground, dark, insulated room. She was held captive by her kidnapper for more than eight years.

During this time, she was reportedly physically abused by her captor, but he had also shown her kindness.

When she eventually escaped, and her captor had committed suicide, it was reported that she ‘wept inconsolably.’ Kampusch denied that she had Stockholm Syndrome and suggested the relationship with her kidnapper was complex.

She said, ‘I find it very natural that you would adapt yourself to identify with your kidnapper, especially if you spend a great deal of time with that person.’

Can Stockholm Syndrome be applied to other situations?

While Stockholm Syndrome is typically associated with hostage situations, it can be applied to various other relationships and circumstances:

Abusive Relationships

Stockholm Syndrome frequently occurs within parent-child dynamics and romantic partnerships.

Children, for example, may form emotional attachments to abusive parents, confusing harmful actions and threats for genuine love and affection.

Individuals in abusive relationships often become emotionally bonded to their abusers, prolonging the cycle of abuse (Cantor & Price, 2007).

Victims may protect their abusers, justify their behavior, or express feelings of love even after the relationship has ended.

Sex Trafficking

Research involving female sex workers in India identified conditions consistent with Stockholm Syndrome, including perceived threats to survival, perceived kindness from traffickers or clients, isolation from the external world, and a sense of inability to escape (Karan & Hansen, 2018).

Remarkably, some women expressed desires to start families with their traffickers or clients.

Sports Coaching

A 2018 study revealed that abusive coaches often victimize young athletes, who may rationalize such abuse as beneficial.

Athletes sometimes endure severe emotional abuse and challenging conditions, believing these experiences improve their performance.

They may sympathize with coaches’ intentions and justify mistreatment as necessary for their training (Baschand & Djak, 2018).

These examples illustrate the complex psychological reactions individuals may experience in various forms of captivity or abuse, highlighting that behaviors akin to Stockholm Syndrome can emerge across diverse contexts beyond traditional hostage situations.

Criticism and Controversy

Stockholm syndrome is not an official diagnosis in the DSM-5 or other psychiatric manuals.

However, many experts question whether it is a unique condition or simply a label for reactions better explained by existing phenomena such as trauma bonding or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Critics argue that the idea of Stockholm syndrome has been largely shaped by high-profile media stories (Namnyak et al., 2008).

Even law enforcement data suggests the phenomenon is rare: an FBI report found only about 5–8% of kidnapping victims showed signs of Stockholm syndrome.

One major literature review found no clear diagnostic criteria and noted that most examples in the literature were only case studies (Namnyak et al., 2008).

Due to this limited evidence, some researchers suggest that “Stockholm syndrome” is more of a pop culture concept than a valid clinical syndrome.

Overall, the debate highlights the controversial and complex nature of this phenomenon in psychology.

Overcoming Stockholm Syndrome

Recovering from Stockholm Syndrome involves various approaches designed to support individuals in regaining emotional independence and mental health. Below are practical methods:

Professional Therapy

Psychotherapy is highly beneficial in addressing Stockholm Syndrome. Therapists often utilize cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to help individuals recognize and change unhelpful thought patterns, process traumatic experiences, and build healthier coping mechanisms.

Support Networks

Reconnecting with supportive friends, family members, or joining support groups provides critical emotional reinforcement.

Open, judgment-free conversations can significantly assist individuals in feeling validated and supported through their recovery process.

Education and Awareness

Learning about Stockholm Syndrome, trauma bonding, and related psychological phenomena empowers individuals by providing context to their experiences.

Understanding their condition can reduce confusion, self-blame, and feelings of isolation.

Building Independence

Developing practical life skills and regaining autonomy helps individuals reduce emotional dependence on their former captors or abusers.

Encouraging independent decision-making and participating in daily activities can gradually restore self-confidence and emotional resilience.

Self-Care and Emotional Wellness

Practicing regular self-care activities such as mindfulness, exercise, adequate rest, and healthy nutrition supports overall mental and physical well-being.

Prioritizing personal wellness is essential in recovering from the effects of trauma and abuse.

How to help someone who may be experiencing Stockholm Syndrome

As a loved one of someone who may have gone through a traumatic event and may be displaying traits of Stockholm Syndrome, there are some ways to support the individual through their emotions:

- Listen without judgment – as the victim is considering everything that has happened to them and they are trying to process their experiences, listen and use reflection to show your concern and validation.

- Avoid polarization – when listening to the victim, it may be unhelpful to try to convince them of the villainous traits of their abuser. This can cause the victim to polarize and defend their captor. They may also not want to share their experiences with you.

- Validate their truth – being the victim of a manipulative relationship can cause cognitive dissonance. This means that the victim’s intuition has been damaged, and they may be confused about their reality. Helping them by validating their truth and encouraging them to trust themselves can be beneficial for them.

- Don’t give advice unless they ask for it – the victim should feel empowered to make their own decisions. If they ask you for advice, then you can give it, but this may be something that they need to work through and make decisions for on their own.

Further information

References

Bachand, C., & Djak, N. (2018). Stockholm syndrome in athletics: A Paradox. Children Australia, 43 (3), 175-180.

Cantor, C., & Price, J. (2007). Traumatic entrapment, appeasement and complex post-traumatic stress disorder: evolutionary perspectives of hostage reactions, domestic abuse and the Stockholm syndrome. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41 (5), 377-384.

Karan, A., & Hansen, N. (2018). Does the Stockholm Syndrome affect female sex workers? The case for a “Sonagachi Syndrome”. BMC international health and human rights, 18 (1), 1-3.

Namnyak, M., Tufton, N., Szekely, R., Toal, M., Worboys, S., & Sampson, E. L. (2008). ‘Stockholm syndrome’: psychiatric diagnosis or urban myth?. 7(1), 4-11.