The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is part of the peripheral nervous system responsible for regulating involuntary bodily functions, such as heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, and pupillary response.

It consists of two main divisions: the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, which often work in tandem to maintaining the body’s internal balance or homeostasis.

Key Takeaways

- Involuntary Control: The ANS automatically regulates critical survival functions, including heart rate, respiration, digestion, and pupil dilation.

- Three Functional Branches:

- Sympathetic: Activates the fight-or-flight response during stress.

- Parasympathetic: Promotes “rest-and-digest” functions during recovery.

- Enteric: Manages the complex neural network of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Homeostasis: The ANS maintains internal stability by constantly balancing the opposing actions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.

- Emotional Impact: Chronic anxiety or trauma can “lock” the ANS in a state of dysregulation, contributing to long-term physical and mental health challenges.

- Consequences of Dysfunction: Damage from aging, injury, or disease can lead to systemic issues such as fainting (syncope), heart rate irregularities, and digestive distress.

The autonomic nervous system differs from the somatic nervous system (another branch of the peripheral nervous system), which is associated with controlling voluntary body movements.

Although most of the functions of the ANS are automatic, they can, however, work in conjunction with the somatic nervous system.

Divisions of the autonomic Nervous system

There are three branches to the ANS; the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system:

- Sympathetic: The “fight-or-flight” system; mobilizes energy, increases heart rate, and redirects blood to muscles during stress.

- Parasympathetic: The “rest-and-digest” system; conserves energy, slows heart rate, and promotes digestion during recovery.

- Enteric: The “second brain”; an independent network of neurons embedded in the gastrointestinal tract that manages digestion and nutrient absorption.

Sympathetic Nervous System

The sympathetic nervous system is involved in responses that help us deal with stress.

It slows bodily processes that are less important in emergencies, such as digestion.

For instance, if the temperature of a room is too hot, the sympathetic system will encourage the body to sweat in response to this change.

When activated, the SNS triggers a cascade of physiological changes:

- Heart and Lungs: Increases heart rate and blood pressure; relaxes bronchi to increase air intake,.

- Vision: Dilates pupils to enhance vision.

- Digestion: Inhibits non-vital functions such as gastrointestinal activity and salivation (causing a dry mouth).

- Energy Mobilisation: Stimulates the liver to release glucose and the adrenal glands to release adrenaline (epinephrine), providing energy for immediate action.

The primary neurotransmitter used by the SNS at the target organ is norepinephrine (noradrenaline)

Fight or Flight Response

The most noticeable function of the sympathetic branch is during the fight-or-flight response.

The sympathetic system activates and releases epinephrine (adrenaline) during threatening or stressful conditions, providing an automatic response.

Sarah walks home alone at night. She hears footsteps behind her. Her heart races, pupils dilate, and she starts to sweat. This is her sympathetic nervous system preparing her to react: either to flee or defend herself.

The purpose of stimulating these bodily responses is to prepare the individual to either escape or fight in dangerous situations.

Although the sympathetic nervous system was evolutionarily used in life-threatening situations, modern-day life, such as work stressors and relationship problems, can also trigger this response.

Similarly, those with anxiety disorders and phobias experience high quantities of epinephrine, resulting in them experiencing the same autonomic responses as in life-threatening situations.

Parasympathetic Nervous System

The parasympathetic nervous system acts to calm the body and conserve energy, often referred to as the rest-and-digest or “rest-and-recover” system.

It becomes dominant after an emergency has passed, working to return the body to its normal resting state.

The pupils will constrict, the heart rate will return to a resting rhythm, and sweating will be reduced or stopped.

The parasympathetic system is therefore important for ensuring we return to normal after a stressful situation.

Without this system, the body will be constantly alert, draining all energy, and this can lead to chronic stress.

This shows how important the parasympathetic is in maintaining homeostasis (a balance in the body).

Anatomically, it is known as the Craniosacral system, as its preganglionic fibres emerge with cranial nerves (III, VII, IX, and X) and from the sacral spinal cord.

The primary neurotransmitter for the parasympathetic system is acetylcholine

Sympathetic vs. Parasympathetic Nervous System

| Organ/System | Sympathetic Nervous System (“Fight or Flight”) | Parasympathetic Nervous System (“Rest and Digest”) |

|---|---|---|

| Heart | Increases heart rate | Decreases heart rate |

| Lungs | Dilates bronchi (more air in) | Constricts bronchi (returns to normal) |

| Pupils | Dilates pupils (better vision in danger) | Constricts pupils (normal vision) |

| Digestive System | Slows digestion | Stimulates digestion |

| Bladder | Relaxes bladder (inhibits urination) | Contracts bladder (promotes urination) |

| Salivary Glands | Inhibits saliva production | Stimulates saliva production |

| Sweat Glands | Activates sweating | No significant effect |

| Liver | Stimulates glucose release | Promotes glucose storage |

| Adrenal Glands | Stimulates adrenaline release | No direct stimulation |

| Reproductive Organs | Decreases function | Stimulates arousal |

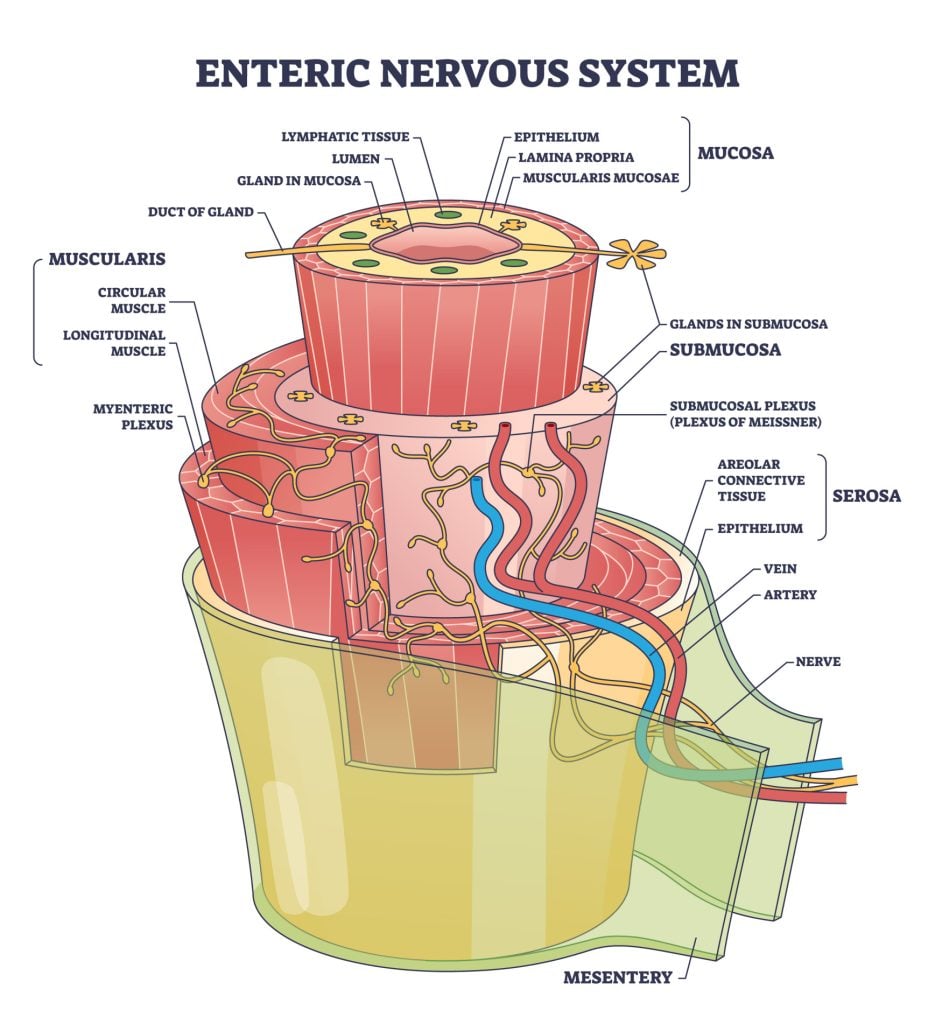

Enteric Nervous System

The Enteric Nervous System (ENS) is a specialized branch of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) that governs the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

It is unique because it can operate autonomously, meaning it can manage digestion even if its connection to the brain is severed.

Key Biological Features

- Independent Circuitry: While it interacts with the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic branches, the ENS contains its own complete reflex arcs that allow it to function without input from the Central Nervous System (CNS).

- Anatomical Location: It consists of a vast network of millions of neurons embedded directly within the walls of the gastrointestinal tract, stretching from the esophagus to the anus.

- Complex Neurochemistry: The ENS uses over 30 neurotransmitters identical to those found in the brain, including acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin. Notably, about 95% of the body’s serotonin is found in the gut.

Primary Functions

- Blood Flow & Defense: Modulating local blood flow to aid absorption and regulating immune responses to protect the body from ingested pathogens.

- Motility: Regulating the rhythmic contraction of muscles (peristalsis) to move food through the digestive tract.

- Secretion: Controlling the release of digestive enzymes, acids, and mucus necessary for breaking down food.

Tthe ENS is bidirectional. It doesn’t just take orders from the brain; it sends a massive amount of sensory information back to the CNS via the Vagus nerve.

This explains why emotional states (like anxiety) can immediately affect digestive comfort (“butterflies” in the stomach).

Neurotransmitters

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) relies on neurotransmitters to regulate involuntary functions such as heart rate, digestion, and respiration.

Three primary chemicals dictate whether an organ is stimulated or inhibited:

- Acetylcholine (ACh): The universal “start” signal at the first synapse (ganglion) for both branches. It is also the primary inhibitory signal for the heart in the parasympathetic branch.

- Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline): The primary excitatory signal for the sympathetic branch at the target organ.

- Epinephrine (Adrenaline): Released as a hormone into the blood to create a widespread, long-lasting “full body” stress response.

| ANS Branch | First Synapse (Ganglion) | Target Organ Synapse | Main Biological Effect |

| Sympathetic | Acetylcholine | Norepinephrine | Increases Heart Rate; Dilates Bronchioles |

| Parasympathetic | Acetylcholine | Acetylcholine | Decreases Heart Rate; Stimulates Digestion |

The Sympathetic “Fight or Flight” Circuit

The sympathetic nervous system is designed for speed and wide distribution.

- Stage 1 (Preganglionic): Short neurons exit the spinal cord and release Acetylcholine at a ganglion.

- Stage 2 (Postganglionic): Long neurons travel to the heart, lungs, or muscles and release Norepinephrine.

- The Adrenal Boost: The system triggers the adrenal medulla to dump Epinephrine and Norepinephrine into the blood. This ensures the “rush” lasts longer than a simple nerve impulse.

3. The Parasympathetic “Rest and Recover” Circuit

The parasympathetic system is more localized and uses only one type of neurotransmitter.

- Stage 1 (Preganglionic): Long neurons exit the brainstem (Vagus nerve) or lower spine and release Acetylcholine.

- Stage 2 (Postganglionic): Short neurons right next to the organ release Acetylcholine again.

- Cholinergic Fibers: Because both stages use ACh, these fibers are called cholinergic.

Dysfunction of the Autonomic Nervous System

ANS Dysfunction (or dysautonomia) is the failure of the involuntary systems to maintain homeostasis.

It occurs when the delicate balance between mobilization (Sympathetic) and restoration (Parasympathetic) is disrupted, often leading to a high allostatic load: the “wear and tear” on the body.

The ANS and Emotional Stress

Chronic stress, anxiety, and trauma can disrupt normal autonomic regulation by overactivating the sympathetic nervous system.

This keeps the body in a prolonged “fight or flight” state: raising heart rate, increasing cortisol, and impairing digestion and sleep.

Over time, this imbalance can lead to exhaustion and health issues.

Researchers believe an overactive autonomic nervous system may be the root cause of panic attacks.

Specifically, poor regulation of the brain’s locus coeruleus (which triggers the fight-or-flight response) may overstimulate the limbic system, leading to chronic anxiety and recurrent panic attacks

ANS Development and Aging

The autonomic nervous system develops gradually after birth and becomes more stable into later childhood and into adulthood.

However, with aging, the ANS may become less responsive.

Older adults often show reduced heart rate variability, slower pupillary responses, and impaired thermoregulation, making them more vulnerable to fainting, temperature extremes, and stress-related health issues.

These changes reflect a natural decline in autonomic flexibility, which can also affect resilience to illness and recovery.

Autonomic Neuropathy/ Disorders Caused by ANS Dysfunction

Autonomic neuropathy refers to the damage of autonomic nerves. These are disorders that can affect the sympathetic nerves, parasympathetic nerves, or both.

The features of autonomic neuropathy include having a fixed heart rate, constipation, abnormal sweating, decreased pupil size, and absent or delayed light reflexes (Bankenahally & Krovvidi, 2016).

There are a number of other disorders which can be the result of ANS dysfunction:

- Acute autonomic paralysis – associated with spinal cord injury, resulting in acute and uncontrolled hypertension.

- Multiple system atrophy – a rare condition that causes gradual damage to the nerve cells. Pure autonomic failure – dysfunction of many processes controlled by the ANS.

- Familial dysautonomia – also known as Riley-Day syndrome. This is an inherited condition where the nerve fibers do not function properly, so these individuals have trouble feeling pain, temperature, pressure, and positioning their arms and legs.

Taking Care of the Autonomic Nervous System

While many autonomic processes happen automatically, lifestyle choices can influence how well the system functions.

Managing stress is key—chronic stress can overactivate the sympathetic system and disrupt balance.

Practices like deep breathing, mindfulness meditation, and yoga help activate the parasympathetic system and promote calm.

Regular physical activity improves heart rate variability and supports overall autonomic tone.

Good sleep hygiene, staying hydrated, and eating a balanced diet rich in fiber and nutrients also support gut health and the enteric nervous system.

Reducing stimulants like caffeine and alcohol may help people who experience sensitivity or dysregulation.

In some cases, people benefit from biofeedback, vagal nerve stimulation, or working with a therapist to manage anxiety or trauma-related ANS imbalance.

Taking care of the autonomic nervous system means maintaining habits that support physical and emotional resilience.

Which division of the autonomic nervous system returns the body to a relaxed condition after an emergency?

The parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system is responsible for returning the body to a relaxed and restorative state after an emergency or stress.

It counteracts the effects of the sympathetic division, which initiates the “fight or flight” response during emergencies. The parasympathetic system promotes “rest and digest” functions, restoring balance and conserving energy.

Which division of the ans can function independently without being stimulated by the central nervous system?

The enteric division of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) can function independently without being stimulated by the central nervous system. It primarily manages the functions of the gastrointestinal tract, including digestion and motility, and can operate autonomously but also communicates with the central nervous system.

Which division of the autonomic nervous system prepares the body for action in a stressful situation?

The sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system prepares the body for action in stressful situations, often referred to as the “fight or flight” response. It increases heart rate, dilates airways, and redirects blood flow to muscles, among other responses, to ready the body for immediate action.

Related articles:

Neurotransmitters: Types, Function and Examples

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS): Parts and Function

Sympathetic Nervous System: Functions & Examples

Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS) Functions & Division