Psychopathology refers to the study of mental disorders in terms of their causes, development, course, classification, and treatment.

Psychopathology describes a wide array of mental health conditions, including but not limited to depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and various personality disorders.

Understanding and studying psychopathology is a crucial part of diagnosing and treating these mental health disorders.

Definitions in the field of mental health

Definitions in the field of mental health; deviation from ideal mental health, deviation from social/cultural norms, failure to function adequately and statistical infrequency.

Deviation from Ideal Mental Health

This definition suggests that a person is considered abnormal if they lack certain characteristics associated with psychological well-being.

Instead of focusing on what makes someone abnormal, this approach defines what “ideal” psychological health looks like, similar to how physical illness is defined by deviations from ideal physical health (e.g., correct temperature, blood pressure).

Jahoda suggested six criteria necessary for ideal mental health. An absence of any of these characteristics indicates individuals as being abnormal, in other words displaying deviation from ideal mental health.

Marie Jahoda (1958) proposed six criteria for ideal mental health:

- Accurate perception of reality: Having an objective and realistic view of the world. For example, a person with manic depression might believe they have superhuman powers in their manic phase.

- Self-actualisation: Fulfilling one’s potential and becoming everything one is capable of becoming.

- Positive attitudes towards the self: Having high self-esteem and a strong sense of identity.

- Environmental mastery: The ability to adapt and thrive in new situations, including being successful in love, work, and leisure.

- Autonomy: Being independent, self-reliant, and able to make personal decisions.

- Resistance to stress: Having effective coping strategies and being able to cope with everyday anxiety-provoking situations. Individuals experiencing anxiety, like Dave in one example, might not easily cope with stress, suggesting a deviation from this ideal.

When individuals fail to meet these criteria, they are seen as deviating from what is considered mentally healthy.

For instance, people with depression often struggle with low self-esteem, difficulty coping with stress, and a lack of motivation or inability to self-actualize.

Strengths:

- Comprehensive and positive focus: This definition outlines a wide range of criteria that help identify mental health issues, set treatment goals, and provide tailored support. It takes into account all facets and behaviours of a person, including their place in the world, lifestyle, and individuality, making it a holistic measure. It is a positive approach that suggests how problems can be overcome, not just what is wrong.

- Real-life application: It can be used as a basis for therapy and treatments, emphasizing positive mental health and well-being.

Limitations:

- Unrealistically high standard: Jahoda’s criteria are almost impossible for most people to meet all at once or maintain for long periods. For example, constantly self-actualizing could be exhausting, and being completely free of stress is not always desirable as stress can be a motivator. This means the majority of the population might be considered abnormal.

- Cultural relativism/Ethnocentrism: The criteria reflect Western individualistic values (like personal growth and autonomy). This makes it less applicable to collectivist cultures (e.g., China, India, Japan) that prioritize community and group well-being over individual achievement. Therefore, it is argued that this definition should only be used in the culture in which it was developed.

Deviation from Social/Cultural Norms

This definition states that a person’s thinking or behavior is classified as abnormal if it violates the unwritten rules, accepted standards, values, or expectations of a particular society or culture.

These social norms are passed on through socialization. Behaviour that breaks these rules is seen as improper or indecent.

It’s crucial to consider the degree and importance of the norm violation. What is considered socially acceptable is constantly changing and varies significantly across cultures and time periods.

For instance, homosexuality was considered abnormal and criminal in the UK until recently, and women having careers was once seen as abnormal.

Strengths:

- Flexibility: This definition is more flexible than statistical infrequency because it adapts to societal standards rather than rigid numerical cut-offs. It allows for desirable traits like high intelligence to be excluded from being classified as abnormal, unlike statistical infrequency.

- Social dimension: It provides a social dimension to the idea of abnormality, offering an alternative to the “sick in the head” individual. It can be a useful tool for assessing behaviour, like identifying antisocial behaviour that might be a symptom of schizophrenia, leading to appropriate treatment. It also helps protect members of society from distressing or harmful acts.

Limitations:

- Cultural relativism/Ethnocentrism: What is considered abnormal varies across cultures, leading to ethnocentrism, where one culture’s standards are used to judge another. For example, hearing voices is perceived as normal spiritual practice in some Afro-Caribbean cultures but misinterpreted as a hallucination (a sign of mental illness) in the West. This can lead to misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment, especially for individuals from non-Western backgrounds living in Western societies.

- Subjectivity and lack of objectivity: Deciding exactly when behaviour deviates enough to be considered abnormal is subjective and open to opinion and interpretation. This contrasts with the objectivity of statistical infrequency.

- Ethical issues/Human Rights Abuse: This definition can be used as a mechanism for social control, persecuting groups that do not adhere to social norms. Historically, conditions like “nymphomania” were fabricated diagnoses to control women.

Failure to Function Adequately

Failure to function adequately (FFA) refers to an abnormality that prevents the person from carrying out the range of behaviours that society would expect, such as getting out of bed each day, holding down a job, and conducting successful relationships, etc.

Rosenhan and Seligman (1989) identified several characteristics of those failing to function adequately:

- Personal distress: The amount of distress a person experiences in response to their behaviour, thoughts, or situation (e.g., severe anxiety in OCD, or profound sadness in depression). Someone may want to interact with the world but struggles to even get out of bed.

- Irrationality: When a person’s behaviour becomes irrational, unpredictable, or dangerous to themselves or others.

- Observer discomfort: When an individual’s behaviour causes distress to those around them (e.g., poor personal hygiene or not respecting others’ personal space).

- Maladaptive behavior: Where an individual’s behaviour goes against their long-term best interests, such as neglecting personal appearance, losing appetite, or disturbed sleep patterns.

Examples include someone struggling to hold down a job due to severe anxiety, or being unable to maintain basic hygiene due to depression.

The more features of personal dysfunction a person has, the more they are considered abnormal.

To assess how well individuals cope with everyday life, clinicians use the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF), which rates their level of social, occupational, and psychological functioning.

Strengths:

- Considers subjective experience: This definition respects the individual and their own personal experience, emotions, and feelings about their behaviour. This is something that other definitions like statistical infrequency often fail to do.

- Practical checklist: It provides a practical checklist of criteria that individuals and clinicians can use to assess the level of abnormality, focusing on observable signs.

Limitations:

- Misses some abnormal behaviors: It fails to identify abnormal behaviours that do not cause personal distress or impairment, such as psychopathic criminal behaviour, where individuals may function normally despite engaging in acts that are clearly abnormal and have negative implications for others.

- Context dependency: What is considered “failing to function adequately” can depend on the context. For instance, not eating is generally failing to function, but prisoners on hunger strike are making a protest and would be seen differently.

- Subjectivity and reliability issues: The decision about whether someone is coping can be subjective and based on the opinion of observers. This means different observers might not agree, making it less reliable.

- Overlap with other definitions: Some behaviours, such as failing to follow interpersonal rules, might also be considered deviation from social norms, leading to overlap between definitions.

Statistical Infrequency

This definition classifies a person’s trait, thinking, or behavior as abnormal if it is rare, uncommon, or statistically unusual within a population.

It uses numerical data and statistics to determine abnormality.

For example, in a normal distribution (a bell-shaped curve), most scores fall around the middle (the mean), while extreme scores at the edges (typically two standard deviations away from the mean) are considered statistically abnormal because they are rare.

Conditions like schizophrenia, affecting about 1% of the world population (0.33% according to one source), are considered abnormal due to their rarity.

Strengths:

- Objectivity: This definition is praised for being objective because it relies on clear numerical cut-off points and statistics, not personal feelings or opinions. This means different mental health professionals can use the same standardized measurements, reducing subjectivity and increasing accuracy. It also provides clear points of comparison between people.

- Real-life application: It is almost always used in clinical diagnoses for mental health disorders as a comparison with a baseline or ‘normal’ value, helping to assess the severity of a disorder.

Limitations:

- Does not consider desirability: This definition fails to distinguish between desirable and undesirable behaviours. For example, having a very high IQ (like Albert Einstein) is statistically rare but highly desirable, and would not be considered a problem requiring treatment.

- Common disorders are missed: It implies that abnormal behaviour should be rare, but many serious mental health disorders are relatively common and would not be classified as statistically infrequent. For instance, depression affects about 10% of the UK population (rising to nearly 20% during the COVID-19 pandemic), and anxiety is also quite common.

- Arbitrary cut-off points: The psychological community subjectively decides where the cut-off point is between statistically normal and abnormal, which can have significant real-world implications, as someone just above the cut-off might be denied treatment.

AO2 Scenario Question

Diane is a 30-year-old businesswoman, and if she does not get her own way, she sometimes has a temper tantrum. Recently, she attended her grandmother’s funeral and laughed during the prayers. When she talks to people, she often stands very close to them, making them feel uncomfortable.

Identify one definition of abnormality that could describe Diane’s behaviour. Explain your choice.

(4 marks)

Answer

“Diana’s behaviour could be defined as deviating from social norms.

Although she is 30 she still has childish temper tantrums, she acted in a socially abnormal way at her grandmother’s funeral and she disobeys social norms about how close it is appropriate to stand to people.

She is deviating from what is regarded as socially normal, thus according to this definition she would be defined as psychologically abnormal.”

AO2 Scenario Question

The following article appeared in a magazine:

‘Hoarding disorder – A ‘new’ mental illness

Most of us are able to throw away the things we don’t need on a daily basis. Approximately 1 in 1000 people, however, suffer from hoarding disorder, defined as ‘a difficulty parting with items and possessions, which leads to severe anxiety and extreme clutter that affects living or work spaces.’

Apart from ‘deviation from ideal mental health,’ outline three definitions of abnormality. Refer to the article above in your answer. (6 marks)

OCD Characteristics

The behavioural, emotional and cognitive characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is an anxiety disorder characterised by intrusive and uncontrollable thoughts (i.e., obsessions) coupled with a need to perform specific acts repeatedly (i.e., compulsions).

Common clinical obsessions are fear of contamination (esp., being infected by germs), repetitive thoughts of violence (killing or harming someone), sexual obsessions, and obsessive doubt. Compulsions are the behavioural responses intended to neutralise these obsessions.

The most common compulsions are cleaning, washing, checking, counting, and touching. To the compulsive, these behaviours often seem to have magical qualities. If they are not performed exactly, “something bad” will happen.

Some O.C.D. sufferers will meticulously perform their rituals hundreds of times and experience extreme anxiety if prevented from carrying them out. Cleaning/washing rituals are more common in women; checking rituals are more common in men.

Behavioural Characteristics:

- Compulsions/Repetitive Behaviours: These are repetitive actions that an individual with OCD feels driven to perform to alleviate the anxiety caused by obsessions. These actions are often rigidly applied and may seem to have “magical qualities” to the sufferer. Common compulsions include checking (e.g., lights, locks), cleaning (e.g., excessive handwashing), counting, and touching. The anxiety reduction is typically only temporary.

- Avoidance: Individuals with OCD may avoid situations or places that trigger their obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviours. This avoidance is negatively reinforced as it helps them avoid anxiety.

- Reduced Social Activity/Social Impairment: Due to the anxiety and the time-consuming nature of compulsions, individuals with OCD can struggle with normal relationships and social engagement, leading to social withdrawal.

Emotional Characteristics:

- Anxiety and Distress: Obsessive thoughts cause intense anxiety and distress. The individual may feel overwhelmed by the need to perform compulsions to reduce this anxiety. This is an uncomfortably high and persistent state of arousal, making relaxation difficult.

- Depression: The constant need to perform compulsive behaviours, which often interfere with daily functioning and relationships, can lead to a low mood and a loss of pleasure in everyday activities.

- Guilt and Disgust: These emotions can be associated with OCD.

- Shame/Embarrassment: Sufferers often experience a sense of shame or embarrassment about their compulsions or thoughts, especially because they recognise their behaviour is not rational or socially acceptable.

Cognitive Characteristics:

- Obsessive Thoughts: These are unwanted, intrusive, persistent, and recurrent thoughts, images, or urges that repeatedly enter the mind and cause anxiety. They can be irrational and embarrassing. Common themes include fear of contamination (germs), repetitive thoughts of violence, sexual obsessions, and obsessive doubt. These can also include catastrophic thoughts.

- Understanding Irrationality/Insight: A hallmark of OCD is the patient’s acknowledgement that their anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions are excessive and irrational, even though they are unable to control them.

- Cognitive Strategies: Patients may develop cognitive strategies to deal with their obsessions, such as always carrying multiple bottles of hand sanitiser.

- Hypervigilance/Selective Attention: This involves an increased awareness of the source of the obsession in new situations or a permanent state of alertness looking for the source of obsessive thoughts. There can also be an attentional bias.

A02 Exam Style Question

Steven describes how he feels when he is in a public place.

I always have to look out for people who might be ill. If I come into contact with people who look ill, I think I might catch it and die. If someone starts to cough or sneeze, then I have to get away and clean myself quickly.

Outline one cognitive characteristic of OCD and one behavioural characteristic of OCD that can be identified from the description provided by Steven. (2 marks)

Hello there! I’m here to be your personal guide to the knowledge base you’ve provided. Think of me as your friendly expert, ready to help you navigate and understand all the source material, whether it’s about approaches in psychology, mental disorders like OCD and schizophrenia, gender development, or even forensic psychology. My goal is to help you access and understand this information quickly and effectively, like a dedicated tutor for your academic materials.

You’ve asked about the biological approach to explaining and treating Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), including genetic and neural explanations, and drug therapy. I’ll provide a comprehensive overview based on the sources you’ve given me.

Biological Approach to OCD

The biological approach to explaining and treating OCD: genetic and neural explanations; drug therapy.

The biological (medical) model of abnormality posits that psychological and behavioural abnormalities stem from biological causes, suggesting that issues with behaviour and experience arise from problems within the brain.

For Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), the biological approach explains its origins through genetic and neural factors, and offers drug therapy as a primary treatment.

Genetic Explanations of OCD

The genetic explanation proposes that OCD is transmitted through genes, meaning individuals can inherit a vulnerability or predisposition to the disorder.

This implies that some people may possess specific genes making them more susceptible to developing OCD.

Evidence for a genetic basis comes from family and twin studies. For instance, Lewis (1936) found that 37% of patients with OCD had parents with the disorder, and 21% had siblings with it.

More recent reviews, such as Nestadt et al. (2010), supported these findings, reporting higher concordance rates for OCD in identical (monozygotic or MZ) twins (68%) compared to non-identical (dizygotic or DZ) twins (31%).

If OCD were purely genetic, identical twins, who share 100% of their DNA, would be expected to have a 100% concordance rate. The fact that it’s not 100% suggests that environmental factors also play a role.

OCD is considered a polygenic condition, meaning that multiple genes are involved in its development. Some sources suggest perhaps as many as 230 different genes could be involved.

This also means OCD is aetiologically heterogeneous, implying that different combinations of genes can lead to different types of OCD in different individuals.

Specific “candidate genes” have been identified that are thought to increase a person’s vulnerability to OCD:

- The COMT gene (catechol-O-methyltransferase) is believed to regulate the production of the neurotransmitter dopamine. A mutated variation of this gene, more common in OCD sufferers, leads to a decrease in COMT activity and, consequently, higher levels of dopamine.

- The SERT gene (serotonin transporter gene) affects the transport of serotonin, potentially lowering its levels. A mutation in this gene has been found in families where a majority of members had OCD.

The diathesis-stress model is often used to explain how these genetic vulnerabilities interact with environmental factors.

This model suggests that while genetics may create a predisposition (diathesis) for OCD, the disorder may only manifest if there is an environmental “stressor” or trigger, such as a traumatic life event.

For example, Cromer et al. (2007) found that over 50% of OCD patients had experienced a traumatic event in their past, with increasing severity of OCD correlating with more traumatic events.

Neural Explanations of OCD

Neural explanations focus on specific brain regions, structures (like neurons), and neurotransmitters involved in the nervous system.

They suggest that abnormalities in these neural mechanisms contribute to OCD symptoms.

Neurotransmitter Levels:

- Serotonin: Low levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, are strongly associated with OCD and obsessive thoughts. It’s thought that serotonin may be removed too quickly from the synapse before it can effectively transmit its signal.

- Dopamine: High levels of dopamine have also been implicated in OCD, particularly linked to compulsive behaviours. Animal studies where drugs enhancing dopamine levels induced stereotyped movements resembling compulsions support this.

Abnormal Brain Circuits/Structures:

Several areas in the frontal lobes of the brain are thought to function abnormally or be overactive in people with OCD.

This is sometimes referred to as the “worry circuit”.

- The Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC): This area is crucial in OCD, as primitive urges related to sex, aggression, danger, and hygiene are thought to originate here. Overactivity in the OFC is linked to a higher frequency of obsessions.

- The Caudate Nucleus: Normally, the caudate nucleus suppresses signals from the OFC to the thalamus about worrying things. However, in OCD, it is believed to be faulty or damaged, failing to suppress these signals, leading to an overactive worry circuit.

- The Thalamus: When the caudate nucleus fails to suppress signals, the thalamus is alerted, which in turn sends signals back to the OFC, reinforcing the worry circuit.

- The Left Parahippocampal Gyrus: Abnormal functioning in this area, located on the underside of the brain near the hippocampus, is linked to increased processing of unpleasant emotions, a feature of OCD.

A limitation of neural explanations is that the relationship observed between neural mechanisms and OCD symptoms is often correlational, making it difficult to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

It is unclear whether the brain changes or neurochemical imbalances cause OCD, are a result of the disorder, or are merely associated.

Drug Therapy for OCD

The biological approach to treating OCD primarily involves drug therapy, which aims to affect levels of neurotransmitter activity in the brain by influencing activity at synapses (gaps between neurons).

The most commonly prescribed drugs for OCD are SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors).

These drugs work by blocking the transporter mechanism that re-absorbs serotonin into the presynaptic neuron after it has fired.

As a result, more serotonin remains in the synapse, allowing for prolonged stimulation of the postsynaptic neuron, which helps to regulate mood and anxiety, thereby reducing obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours.

Dosages vary, and it typically takes 3-4 months for the full benefits to show.

Other drugs may be prescribed if a patient does not respond well to SSRIs. These include:

- Tricyclics, such as Clomipramine, which work similarly to SSRIs but block the reuptake of both serotonin and noradrenaline. They tend to have more side effects.

- SNRIs (Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors), which work on both noradrenaline and serotonin.

- Benzodiazepines (BZs), which are anti-anxiety drugs that enhance the activity of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), slowing down the central nervous system and causing relaxation.

Evaluation of Drug Therapy:

- Effectiveness: Studies, such as a meta-analysis by Soomro et al. (2009), have shown that SSRIs are significantly more effective than placebos in reducing OCD symptoms, at least in the short term (within 6 to 13 weeks).

- Ease and Non-Disruptiveness: Compared to psychological treatments, drug therapy is often considered easier and less disruptive, as patients simply take a pill rather than attending lengthy therapy sessions. This can make treatment more accessible for people regardless of their lifestyle. They are also generally cost-effective compared to psychological treatments.

- Side Effects: A significant weakness is the potential for side effects, including indigestion, loss of sex drive, blurred vision, weight gain, aggression, nausea, headaches, and insomnia. These can make patients less willing to continue treatment, leading to symptom recurrence.

- Symptom vs. Cause: Drug therapies often treat the symptoms of OCD rather than addressing the underlying cause. This is known as the “treatment etiology fallacy” – just because a drug reduces symptoms doesn’t mean the lack of that chemical was the cause in the first place, similar to how aspirin treats a headache but a headache isn’t caused by a lack of aspirin. If the true cause is, for example, psychological trauma, drug therapy might only offer temporary relief.

- Partial Improvement: Some studies indicate that 40-60% of patients show no or only partial symptom improvement, suggesting that low serotonin is not the sole cause.

- Comparison with CBT: While drug therapy can be faster and requires less motivation than Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), CBT is often considered more empowering as it actively involves patients in challenging their thoughts, giving them a greater sense of control. However, drug therapy might be the only option for those with severe depression or low motivation.

Overall Evaluation: Issues and Debates

The biological approach to OCD, and psychology in general, frequently engages with several key debates:

- Nature vs. Nurture: The biological approach strongly supports the “nature” side, emphasizing the role of genes, biological structures, and neurochemistry. However, the concept of genotype and phenotype acknowledges the interaction between an individual’s genetic code and environmental influences on observable characteristics. Furthermore, the diathesis-stress model explicitly highlights that both inherited vulnerability (nature) and environmental stressors (nurture) are necessary for the disorder to develop.

- Determinism: The biological approach is largely biologically deterministic, proposing that human behaviour is governed by internal biological causes over which individuals have no control, such as genes and brain chemistry. This can have implications for moral responsibility and may be perceived as pessimistic for sufferers.

- Reductionism: The biological approach is considered reductionist because it explains complex human behaviour by breaking it down into simpler, more fundamental biological components, such as genes, neurons, and neurotransmitters. While this allows for scientific study and the development of drug treatments, critics argue it may oversimplify and overlook the complex interaction of many factors or the holistic experience of an individual.

- Nomothetic Approach: The biological approach generally adopts a nomothetic approach, aiming to establish general laws about behaviour from the study of large groups of people using quantitative and scientific methods, such as scanning techniques, twin studies, and drug trials. This approach is seen as highly scientific due to its objectivity, control, and reliability.

Depression Characteristics

The behavioural, emotional and cognitive characteristics of depression.

Depression is classified as a mood or affective disorder, characterised by a continuous state of sadness and low mood.

It involves a collection of physical, emotional, mental, and behavioural experiences that are severe, prolonged, and damaging to everyday functioning.

A diagnosis often requires at least five or more symptoms, with low mood or loss of pleasure being essential for diagnosis in some systems.

Behavioural Characteristics:

- Changed Activity Levels: Depression can lead to increased lethargy and a lack of energy, causing withdrawal from previously enjoyable activities (anhedonia). It may also result in psychomotor agitation or, conversely, an inability to get out of bed. Poor hygiene can also be notable.

- Changes in Sleep Patterns: Sufferers may experience insomnia (reduced sleep) or hypersomnia (increased sleep).

- Changes in Eating Patterns: Appetite can be disrupted, leading to significant weight gain or loss.

- Aggression: This can be directed towards others or manifest as self-harm.

Emotional Characteristics:

- Depressed Lowered Mood: A continuous state of sadness that differs from temporary low moods.

- Lowered Self-Esteem/Self-Worth: Individuals often express feelings of having a low view of themselves, sometimes to the point of self-hatred. They may experience guilt linked to helplessness and feelings of worthlessness.

- Loss of Pleasure (Anhedonia): A significant reduction or complete loss of interest and enjoyment in activities that were once pleasurable.

- Anger: High levels of anger can be present, directed both towards oneself and others.

Cognitive Characteristics:

- Difficulty Concentrating: Poor concentration levels are common, affecting decision-making and the ability to focus on tasks, even simple ones.

- Negative Thinking: Sufferers tend to dwell on negativity, overlooking positive aspects of situations. This includes irrational thoughts.

- Beck’s Cognitive Triad: This theory explains depression through three key elements: negative self-schemas (negative views of themselves), cognitive distortions (distorted negative interpretations of life events like overgeneralization or catastrophizing), and the negative triad (a pessimistic view of themselves, the world, and the future).

- Absolutist Thinking: Jumping to irrational conclusions, such as believing they are a “failure of a son” for missing an event.

- Selective Attention to Negative Events: Patients often recall only negative events, ignoring positive ones.

- Recurrent Thoughts of Death: This is another cognitive symptom.

- Low Confidence: A common cognitive characteristic.

AO2 Scenario Question

Ben recently moved away from home to go to university. He loved his new life of going out, meeting new friends, and his new university course. However, after a while, he struggled to get out of bed and started to become very tired.

His eating patterns changed, and he lost a lot of weight. He noticed that he got angry at little things and snapped at his friends. When he sat in lectures, he found it hard to concentrate for long periods of time.

Identify the behavioural, emotional, and cognitive aspects of Ben’s state. (3 marks)

Cognitive Approach to Depression

The cognitive approach to understanding and treating depression focuses on the idea that internal mental processes, particularly dysfunctional or irrational thinking, are the primary cause of emotional and behavioural problems like depression.

This approach contrasts with others by making inferences about mental processes that cannot be directly observed.

Here’s how the cognitive approach explains and treats depression:

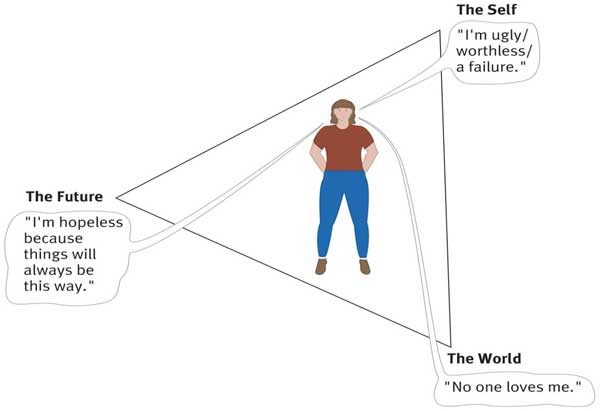

Beck’s Negative Triad

According to Beck, depressed individuals have distorted and unrealistically negative ways of thinking about themselves, their experiences, and their future.

- Self: For example, depressed individuals tend to view themselves as helpless, worthless, and inadequate.

- World Experiences: They interpret events in the world in an unrealistically negative and defeatist way, and they see the world as posing obstacles that can’t be handled.

- Future: Finally, they see the future as totally hopeless because their worthlessness will prevent their situation from improving.

These negative thinking patterns are influenced by:

- Negative self-schemas: These are deeply held, negative, and pessimistic beliefs and expectations about oneself, often developing in childhood due to criticism or rejection from significant others. These schemas bias how a person interprets events in their life.

- Cognitive biases: These are exaggerated or irrational thought patterns that arise from negative self-schemas, causing distorted interpretations of life events. Examples include:

- Overgeneralising: Making sweeping conclusions based on a single incident.

- Catastrophising: Exaggerating a minor incident and believing it to be a major disaster.

- Selective abstraction: Focusing only on negative details while ignoring positive ones.

- Absolutist thinking: Thinking in ‘black and white’ terms, such as “I am a failure if I can’t do X”.

These factors collectively reinforce the negative triad, leading to a pessimistic view of the self, the world (perceiving it as hostile and full of insurmountable obstacles), and the future (assuming things will always turn out badly).

This theory suggests that secondary symptoms of depression, such as a lack of motivation, can be understood as a result of this core of negative beliefs.

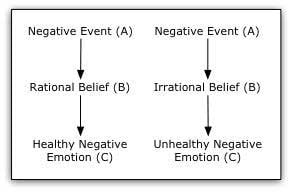

Ellis’ ABC Model

Albert Ellis’s ABC model explains depression by focusing on how irrational thoughts influence emotions and behaviour.

According to Ellis, depression arises not directly from an activating event, but from a person’s irrational beliefs about that event.

The model consists of three components:

- A – Activating Event: This is a situation or event that occurs in someone’s life, which can be minor or major.

- B – Beliefs: This refers to the thoughts a person has about the activating event. These beliefs can be either rational or irrational. Irrational beliefs, such as “musturbatory thinking” (the idea that certain things must be true for happiness, like “I must be valued by others”), lead to unhealthy emotional responses.

- C – Consequences: These are the negative feelings and behaviours that result from the irrational beliefs. If beliefs are rational, the consequences are healthy emotions and better mental well-being.

According to Ellis, depression does not occur as a direct result of a negative event but rather is produced by irrational thoughts (i.e., beliefs) triggered by negative events.

Ellis believes that it is not the activating event (A) that causes depression (C) but rather that a person interprets these events unrealistically and therefore has an irrational belief system (B) that helps cause the consequences (C) of depressive behaviour.

For example, some people irrationally assume that they are failures if they are not loved by everyone they know (B) – they constantly seek approval and repeatedly feel rejected (C).

All their social interactions (A) are affected by this assumption, so a great party can leave them dissatisfied because they don’t get enough compliments.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is the main cognitive treatment for depression.

It is a structured talking therapy that aims to help individuals manage their problems by changing their thought patterns and resulting behaviours.

CBT operates on the assumption that irrational or faulty thinking patterns lead to emotional and behavioural problems.

CBT builds on both Beck’s and Ellis’s models:

Based on Beck’s Model: Beck’s cognitive therapy involves techniques to identify and challenge the patient’s negative triad and cognitive biases.

- Thought Catching/Diary Records: Patients identify and record their irrational thoughts and negative views of themselves, the world, and the future. This is often done by keeping a thought diary.

- Patient as Scientist / Reality Testing: The therapist encourages the patient to generate and test hypotheses about the validity of their irrational thoughts. They collect evidence for and against their thoughts in real-life situations to see if their beliefs match reality.

- Behavioural Activation: Patients are encouraged to engage in enjoyable activities that they used to participate in, to help improve their mood and provide counter-evidence to negative beliefs.

Based on Ellis’s REBT (Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy):

Ellis’s version of CBT extends his ABC model to include D for Disputing and E for Effects.

The therapist actively challenges the client’s irrational beliefs through “vigorous argument”. Types of disputing include:

- Logical Disputing: Questioning whether the irrational thoughts make sense or logically follow from the facts.

- Empirical Disputing: Challenging the client to provide evidence for their irrational beliefs, showing they are not consistent with reality.

- Pragmatic Disputing: Asking how practical and helpful believing those thoughts actually are.

The effect (E) of disputing these irrational thoughts is to help the person think more rationally and change how they feel about the situation, leading to improved emotional well-being and behaviour.

CBT sessions typically involve regular meetings (e.g., 5-20 sessions) and often include “homework” assignments for the patient to practice identifying and challenging irrational thoughts in everyday life.

AO2 Scenario Question

Jack suffers from depression. His symptoms include loss of concentration, lack of sleep, and struggles to sleep at night. He finds himself having absolutist thoughts that everything is negative and bad all the time.

How might a cognitive behaviour therapist tackle Jack’s depression? (4 marks)

Evaluation of CBT for Depression:

- Effectiveness: CBT has shown to be very effective in treating depression. A study by March et al. (2007) found that CBT, drug treatment, and a combination of both all improved depression symptoms in adolescents. The combined treatment was found to be the most effective after 36 weeks (86% improvement), with CBT alone showing 81% effectiveness, similar to drug therapy (81%).

- Comparison with Drug Therapy:

- CBT avoids the negative side effects and withdrawal symptoms associated with biological treatments like antidepressant drugs.

- Drug treatments can work faster and require less motivation and commitment compared to the demanding nature of CBT.

- CBT is often seen as more empowering because it actively involves the patient in challenging and changing their thoughts, giving them a greater sense of control over their condition, unlike the passive role with medication.

- Commitment and Motivation: CBT requires significant commitment and motivation from the patient. Patients with severe depression may struggle to engage consistently due to low energy, poor concentration, or feelings of hopelessness.

- Focus on Present vs. Past: CBT primarily focuses on present problems and current circumstances, often not exploring past traumatic events that might contribute to depression. This can frustrate patients who believe their past is relevant to their condition.

- Blaming the Patient: A criticism is that the cognitive approach may “blame the patient” by focusing solely on their thoughts as the cause of depression, potentially overlooking external situational factors like domestic abuse or financial problems that require practical solutions beyond changing thinking patterns.

- Correlational Nature: It is not always clear whether faulty cognitions are a cause or a consequence of depression, as the relationship can be correlational.

- Scope of Explanation: Cognitive explanations may not fully account for all aspects of depression, such as physical symptoms, extreme anger, or manic phases seen in bipolar disorder.

CBT is also adapted and used in the treatment of other conditions, such as schizophrenia (CBTp), where it helps patients identify and correct distorted beliefs, such as delusions and hallucinations, by reality testing.

Phobia Characteristics

The behavioural, emotional and cognitive characteristics of phobias.

Phobias are a type of anxiety disorder characterised by an extreme and irrational fear of a specific object or situation.

This fear is excessive or unreasonable, and it significantly interferes with an individual’s daily life, distinguishing it from normal fears.

The symptoms of phobias can be placed into one of three categories:

Behavioural Characteristics:

- Panic: Individuals with phobias often experience panic when encountering their feared object or situation. This can manifest as crying, screaming, freezing, sweating, running away, fainting, or even vomiting. This panic is a result of heightened physiological arousal, triggered by the hypothalamus activating the sympathetic nervous system.

- Avoidance: A defining characteristic is the strong urge to avoid the phobic stimulus. People will go to great lengths to steer clear of anything that triggers their anxiety. This avoidance behaviour is negatively reinforced because it reduces the unpleasant feeling of anxiety, thereby maintaining the phobia. This often leads to significant disruptions in their normal daily routine and ability to function.

- Endurance: In some cases, a person might remain exposed to the phobic stimulus for an extended period, but they will still experience heightened levels of anxiety throughout this time. This could involve remaining frozen still, such as not leaving a meeting.

Emotional Characteristics:

- Anxiety: This is the primary emotion associated with phobias. It presents as an intense, persistent dread and worry about the feared object or situation. This leads to an uncomfortably high and persistent state of arousal, making it difficult for the person to relax or experience positive emotions.

- Fear: Coupled with anxiety, there is an intense experience of fear, which is linked to the body’s fight-or-flight response, leading to an increased heart rate and breathing rate. This intense emotional sensation of extreme and unpleasant alertness only subsides once the phobic object is removed.

- Irrationality of Fear/Anxiety: Individuals are often aware that their fear is excessive or unreasonable, and that the level of anxiety caused is disproportionate to the actual threat posed by the stimulus.

Cognitive Characteristics:

- Irrational Beliefs: People with phobias frequently hold irrational beliefs, thinking the feared object or situation is far more dangerous than it actually is. These beliefs contribute to unreasonable anxiety responses and are not easily reduced by reasoning.

- Selective Attention: Sufferers tend to focus disproportionately on the feared object or situation, even when it causes severe anxiety, ignoring other less threatening stimuli. This can impair their ability to concentrate on other tasks.

- Cognitive Distortions: The patient’s perception of the phobic stimulus may be inaccurate, appearing grossly distorted or irrational.

Behavioural Approach to Phobias

The behavioural approach in psychology focuses on observable and measurable behaviour, arguing that all behaviour is learned from our environment.

Behaviourists believe that humans and animals learn in similar ways, meaning that findings from animal studies can often be extrapolated to human behaviour.

This approach emphasizes scientific methodology, using laboratory experiments to ensure objectivity, control over variables, and precise measurement, which contributes to psychology’s scientific credibility.

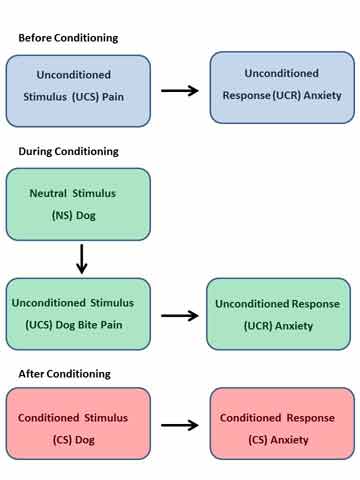

The Two-Process Model

The behavioural approach explains the development and maintenance of phobia, mainly using the theories of classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

These were first combined as a single explanation for phobia by Mowrer in the two-process model of phobia.

According to behaviourists, phobias are the result of a classically conditioned association between an anxiety-provoking unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and a previously neutral stimulus.

For example, a child with no previous fear of dogs gets bitten by a dog and, from this moment onwards, associates the dog with fear and pain.

Due to the process of generalization, the child is not just afraid of the dog who bit them but shows a fear of all dogs.

Operant conditioning can help to explain how the phobia is maintained.

When an individual avoids the feared object or situation (phobic stimulus), they experience a reduction in anxiety and distress.

This relief acts as a negative reinforcement, strengthening the avoidance behaviour and making it more likely that the person will continue to avoid the phobic object or situation in the future, thus maintaining the phobia.

A02 Questions

Kirsty is in her twenties and has had a phobia of balloons since one burst near her face when she was a little girl. Loud noises such as ‘banging’ and ‘popping’ cause Kirsty extreme anxiety, and she avoids situations such as birthday parties and weddings, where there might be balloons.

Suggest how the behavioural approach might be used to explain Kirsty’s phobia of balloons. (4 marks)

There is empirical support to show how classical conditioning leads to the development of phobias.

Watson and Rayner (1920) used classical conditioning to create a phobia in an infant called Little Albert. Albert developed a phobia of a white rat when he learned to associate the rat with a loud noise.

The behaviourist approach adopts a limited in the origins of a phobia, as it overlooks the role of cognition. Ignoring the role of cognition is problematic, as irrational thinking appears to be a key feature of phobias.

Tomarken et al. (1989) presented a series of slides of snake and neutral images (e.g., trees) to phobic and non-phobic participants. The phobics tended to overestimate the number of snake images presented.

In theory, anyone could develop a phobia of a potentially harmful object, although this does not always happen. Despite the fact that most adults have either experienced, witnessed or heard about car accidents where another person is injured, the phobia of cars is virtually non-existent.

Seligman (1970) suggests that humans have a biological preparedness to develop certain phobias rather than others because they were adaptive (i.e., helpful) in our evolutionary past.

For example, individuals that avoided snakes and high places would be more likely to survive long enough and pass on their genes than those who did not.

The idea of biological preparedness is further supported by Ost and Hugdahl (1981), who claims that nearly half of all people with phobias have never had an anxious experience with the object of their fear, and some have had no experience at all.

For example, some snake phobics have never encountered a snake.

The cognitive approach criticises the behavioural model as it does not take mental processes into account.

They argue that the thinking processes that occur between a stimulus and a response are responsible for the feeling component of the response.

Behavioural Treatments for Phobias

Behavioural therapies for phobias aim to replace the learned fear association with a new, more positive association, typically relaxation.

This process is known as counter-conditioning. It relies on the principle of reciprocal inhibition, which states that two opposite emotional states, such as fear and relaxation, cannot coexist simultaneously.

Systematic Desensitisation (SD)

Systematic desensitisation is a gradual behavioural therapy designed to reduce phobic anxiety through step-by-step exposure to the phobic stimulus. The process typically involves three key components:

- Relaxation: The patient is first taught deep muscle relaxation techniques, such as breathing exercises or progressive muscle relaxation. The goal is to reduce the activity of the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response) and activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Anxiety Hierarchy: The patient and therapist collaboratively create a step-by-step list of situations involving the phobic stimulus, ordered from the least anxiety-provoking to the most terrifying.

- Gradual Exposure: The patient then gradually works their way up the anxiety hierarchy over several sessions, applying the learned relaxation techniques at each stage. They only progress to the next level when they can remain completely calm and relaxed at the current one. Exposure can be “in vitro” (imagining the phobic stimulus) or “in vivo” (actual exposure), and virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) can also be used as an “in vitro” form of SD. The phobia is considered cured when the patient can remain calm at the highest level of the hierarchy.

Strengths and Evidence for SD:

- Effectiveness: Research by Gilroy et al. (2003) showed that 42 patients treated for spider phobia in three SD sessions reported reduced fear at 3 and 33 months compared to a control group, supporting its long-term effectiveness. Rothbaum et al. (2000) also found significant improvement in individuals with a fear of flying using VRET, comparable to traditional exposure therapy.

- Suitability for Diverse Patients: SD is suitable for a wide range of patients, including those with learning difficulties, as it does not require complex cognitive engagement or evaluation of thoughts, making it a viable alternative to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

- Acceptability: Patients tend to find SD more acceptable due to its gradual nature and sense of control, leading to lower refusal and attrition (dropout) rates compared to more intense therapies like flooding. It is generally less traumatic than flooding.

Limitations of SD:

- Time-Consuming: SD can be a slow process, often requiring multiple sessions (e.g., 6-8 sessions on average).

- Limited Generalisability: The effectiveness of SD may sometimes be limited to the controlled environment of the therapist’s office and may not fully translate to real-world experiences, where phobias might resurface.

- Effectiveness for Complex Phobias: SD may be less effective for more complex phobias, such as social phobias, which involve significant cognitive aspects like irrational thoughts, where cognitive therapy might be more appropriate.

Flooding

Flooding is a behavioural therapy that contrasts sharply with systematic desensitisation.

It involves exposing the patient to their most feared phobic stimulus immediately and intensely, without any gradual build-up or avoidance options.

The exposure occurs in a safe and controlled environment from which the patient cannot escape.

The underlying principle of flooding is that fear is a time-limited response.

Initially, the patient experiences extreme anxiety and panic.

However, since the phobic object or situation is not actually harmful, and escape or avoidance is prevented, the patient’s anxiety cannot be maintained indefinitely and will eventually subside due to exhaustion.

This prolonged, intense exposure creates a new, positive association (e.g., a sense of calm) with the feared object, leading to the extinction of the fear response.

Strengths of Flooding:

- Cost-Effective and Quicker: Flooding is generally considered more cost-effective and quicker than systematic desensitisation or cognitive therapies because phobias can often be cured in a single, immersive session lasting 2-3 hours.

- Effectiveness: For those who can complete the session, flooding can be a highly effective form of treatment, sometimes more effective than SD. Its success supports the hypothesis that phobias persist due to avoidance, which prevents extinction.

Limitations of Flooding:

- Highly Traumatic and Distressful: Flooding is a highly traumatic experience that can cause significant emotional distress and even emotional harm to the patient.

- Risk of Reinforcing Phobia: If flooding is not conducted properly, or if the patient exits the therapy session before their anxiety subsides, it can actually reinforce the phobia, making it worse. Wolpe (1969) reported a case where flooding led to a client’s hospitalisation.

- Not Suitable for All: Flooding is not appropriate for all patients, especially those with underlying medical conditions (e.g., heart conditions) or young children, due to the extreme anxiety it induces. It is also less effective for complex phobias like social phobias that have a strong cognitive component.