These revision notes cover the Approaches in Psychology subtopic (3.2.1) from the AQA A-level Psychology syllabus: Paper 2: Psychology in Context.

They are structured to distinguish between AO1 (demonstrate knowledge and understanding) and AO3 (analyse, interpret, and evaluate).

- AS Level includes Learning, Cognitive, and Biological approaches.

- A Level adds Psychodynamic, Humanistic, and Comparison of Approaches.

Learning Approaches

Learning approaches: i) the behaviourist approach, including classical conditioning and Pavlov’s research, operant conditioning, types of reinforcement and Skinner’s research; ii) social learning theory including imitation, identification, vicarious reinforcement, the role of mediational processes and Bandura’s research.

Behaviourism

Assumptions (AO1)

- All behaviors are learned from our environment. The behaviourist approach argues we are born as a blank slate (tabula rasa) and our experiences (stimuli) shape our actions.

- Only observable, measurable behavior is worthy of study – no reference to internal mental states, since those cannot be objectively seen or measured.

- Animals and humans learn in the same ways, so behaviorists carry out experiments on animals and extrapolate the results to humans.

- Psychology should be scientific and objective therefore behaviorists use mainly laboratory experiments to achieve this.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is a type of learning that occurs through association.

It was first famously demonstrated by Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, in the early 1900s during his research into the digestive system of dogs.

Pavlov’s Experiment:

Pavlov noticed that dogs naturally salivated (an unconditioned response or UCR) when presented with food (an unconditioned stimulus or UCS).

He then introduced a neutral stimulus (NS), such as a bell or a metronome, which initially produced no response from the dogs.

During conditioning, Pavlov repeatedly paired the neutral stimulus with the unconditioned stimulus (e.g., ringing the bell just before presenting food).

After several repetitions, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell alone.

The bell had become a conditioned stimulus (CS), eliciting a conditioned response (CR) of salivation, even without the presence of food.

Key Concepts in Classical Conditioning:

- Extinction: If the conditioned stimulus (e.g., the bell) is continually presented without the unconditioned stimulus (food), the conditioned response (salivation) will gradually die out or extinguish.

- Spontaneous Recovery: After a period of rest, an extinguished conditioned response may reappear if the conditioned stimulus is presented again.

- Stimulus Generalisation: A conditioned response can be elicited by stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus. For example, Little Albert, after being conditioned to fear a white rat, also developed a fear of other white fluffy objects like a Santa Claus hat.

- Stimulus Discrimination: The conditioned response is produced only by the original stimulus, not extending to similar stimuli.

Classical conditioning has practical applications, such as in the treatment of phobias through systematic desensitization and aversion therapies for addictions.

Strengths of Classical Conditioning:

- Scientific Credibility and Objectivity: Classical conditioning, as part of the behaviourist approach, strongly emphasizes objectivity, control over variables, and precise measurement.

This makes the studies highly reliable and is credited with introducing the scientific method into psychology.

Researchers like Pavlov and Skinner established clear cause-and-effect relationships using controlled laboratory experiments, which significantly enhanced psychology’s scientific credibility. - Real-World Applications and Practical Solutions: The principles of classical conditioning have proven to be highly applicable in real-world settings, offering practical solutions to many human problems.

- Treatment of Phobias: One of its most significant applications is in the treatment of phobias, through therapies like systematic desensitisation and flooding. These behavioural principles underpin successful counter-conditioning techniques.

For instance, systematic desensitisation helps replace a learned fear with a relaxing response through gradual exposure, a process known as counter-conditioning.

Flooding immediately exposes an individual to their feared stimulus until anxiety subsides, based on the principle of extinction. - Addiction Treatments: It also forms the basis of behavioural interventions for addiction, such as aversion therapy and covert sensitisation, which have demonstrated effectiveness.

Aversion therapy aims to change the association of a substance with pleasure to an association with an unpleasant state through repeated pairings.

- Treatment of Phobias: One of its most significant applications is in the treatment of phobias, through therapies like systematic desensitisation and flooding. These behavioural principles underpin successful counter-conditioning techniques.

- Clear Explanatory Power: Classical conditioning provides a clear and straightforward explanation of how associations are formed between stimuli and responses. It specifically explains the acquisition, or initial learning, of a response.

- Pliable View of Human Behaviour: This approach views humans as pliable, suggesting that abnormal behaviours are acquired through learning and can therefore be “unacquired” or treated.

This offers hope for individuals suffering from conditions like phobias, by providing techniques to change these learned behaviours.

Limitations of Classical Conditioning:

- Reductionist and Oversimplistic: Classical conditioning is often criticised for being reductionist, meaning it attempts to explain complex human behaviour by breaking it down into simple stimulus-response (S-R) links.

This oversimplifies human experience by ignoring internal mental processes, conscious choice, and potentially crucial biological factors. - Hard Environmental Determinism: The behaviourist approach, including classical conditioning, is rooted in a hard deterministic view, suggesting that virtually all behaviour is determined by past conditioning experiences and environmental factors.

This stance implies individuals have little to no free will or personal responsibility, which can be controversial and has implications for legal and moral accountability. - Problematic Generalisability from Animal Research: A significant amount of the research supporting classical conditioning, particularly Pavlov’s work, was conducted on animals like dogs and rats.

This raises concerns about the extent to which these findings can be generalised to complex human behaviour, which involves more intricate cognition and emotions not fully accounted for in animal models. - Ethical Concerns in Research: The animal studies conducted to demonstrate classical conditioning often involved exposing animals to stressful or harmful conditions, such as electric shocks in Skinner’s box, which raise significant ethical concerns.

Furthermore, human studies, like Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert experiment, deliberately induced fear in an infant and are considered highly unethical by modern standards. - Artificiality and Lack of Ecological Validity: Many classical conditioning experiments are conducted in highly controlled laboratory settings.

While this allows for strict variable control, it can create artificial conditions that may not accurately reflect real-world contexts.

This can limit the ecological validity and generalisability of the findings to everyday life. - Neglect of Internal Mental Processes: Traditional classical behaviourism purposely avoids the study of mental states and internal processes, considering them a “black box” unsuitable for scientific investigation because they cannot be directly observed or measured.

This led to criticism from the later cognitive psychologists who argued that internal processes should be studied to fully understand learning. - Biological Constraints and Preparedness: A significant limitation is its struggle to explain why certain associations are learned more easily than others, or why phobias are often restricted to a small range of objects.

Pavlov’s concept of “equipotentiality” (that any stimulus could become a conditioned stimulus if associated with an unconditioned stimulus) is challenged by research on taste aversion.

This research demonstrates that organisms have a biological predisposition to learn certain associations more readily (e.g., taste with illness, but not light/noise with illness), suggesting that biological factors play a crucial role in determining what can be conditioned. - Contiguity Not Always Sufficient: Pavlov believed that temporal contiguity (the close timing of stimuli) was necessary and sufficient for learning.

However, some psychologists, like Tolman, argued that learning involves more than just mechanistic stimulus-response associations; they suggested that organisms learn ‘expectancies’ or that the conditioned stimulus becomes a reliable predictor of the unconditioned stimulus.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is a type of learning where behaviour is acquired and maintained based on its consequences. Behaviour is “shaped and maintained by its consequences”.

Types of Reinforcement:

Reinforcement increases the likelihood that a particular behaviour will be repeated.

- Positive Reinforcement: Occurs when something desirable is added or given (a reward) following a behaviour, which strengthens the behaviour and makes it more likely to be repeated. Examples include a rat getting food for pressing a lever, or a student receiving praise for homework.

- Negative Reinforcement: Occurs when something unpleasant is removed or avoided following a behaviour, which also strengthens the behaviour and makes it more likely to be repeated.

For instance, a rat pressing a lever to stop an electric shock, or taking painkillers to remove pain. In the context of phobias, avoiding a feared stimulus removes anxiety, reinforcing the avoidance behaviour.

Punishment: Punishment is an unpleasant consequence that decreases the probability of a behaviour being repeated.

Skinner’s Research:

B.F. Skinner greatly simplified and automated instrumental conditioning, renaming it operant conditioning.

He developed the “Skinner Box” (also known as an operant conditioning chamber), a highly controlled setting to study the effects of reinforcement and punishment on animals like rats and pigeons.

The box had a lever (or disk for pigeons), a light, a sound source, and a food delivery mechanism.

Skinner found that behaviours which were reinforced tended to be repeated, while behaviours that were punished declined.

He also discovered that intermittent (partial) reinforcement schedules, where rewards are given unpredictably, caused a higher rate of responding and were more resistant to extinction than continuous reinforcement.

This principle is observed in phenomena like gambling addiction.

Skinner, like Watson, was a nomothetic psychologist, aiming to establish general laws of behaviour that apply to everyone.

His work gave psychology greater scientific credibility due to its use of highly scientific, objective methods in controlled lab settings.

Applications (AO3)

Behaviorism has increased our understanding of the causes of attachment.

The learning theory of attachment suggests that attachment is a set of learned behaviors instead of innate biological behavior. The basis for the learning of attachments is the provision of food.

This theory encompasses two types of learning: classical conditioning, where an infant learns to associate the caregiver with comfort and eventually forms an attachment.

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, assumes that infants are in a drive state of internal tension or discomfort, and their actions focus on removing this discomfort.

The principles of conditioning have been successfully applied in the real world, such as treatments for phobias.

For example, systematic desensitisation (which works by gradually associating calm responses with feared stimuli) – a therapy that is quick and requires less conscious effort from patients (suitable for those who might not be introspective).

Operant conditioning underlies token economy systems used in prisons and psychiatric hospitals (desirable behaviors rewarded with tokens exchangeable for privileges).

Strengths of Operant Conditioning

-

Scientific Credibility and Objectivity Operant conditioning, central to the behaviourist approach, places a strong emphasis on scientific methodology. Behaviourists insist on objectivity, control over variables, and precise measurement.

This approach means that studies conducted by behaviourists, such as B.F. Skinner’s work with the ‘Skinner Box’, tend to be highly reliable and contribute significantly to psychology’s scientific credibility.

Skinner’s experiments allowed for clear cause-and-effect conclusions to be drawn about reinforcement and behaviour because he could carefully control and manipulate different variables and measure the behaviour, such as the number of times a rat pressed a lever or the time taken to do so.

This objective and quantifiable data enhances the replicability and validity of the conclusions. -

Real-World Applications and Practical Solutions The principles of operant conditioning have supplied practical solutions to many human problems and are widely applicable in real-world settings.

- Behaviour Modification: One of its most significant applications is in behaviour modification, especially in institutions like schools, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals.

Token economy systems, for instance, are based on operant conditioning principles, where desirable behaviours are positively reinforced with tokens that can be exchanged for privileges or rewards.

Studies like Hobbs and Holt (1976) demonstrated that such systems could significantly increase appropriate behaviour in young delinquents.

These systems are relatively easy to administer and manage and do not require specialist professionals, making them a simple way to deal with challenging behaviours. - Treatment of Addictions: Operant conditioning explains why addictive behaviours like smoking and gambling are maintained.

Positive reinforcement (e.g., the euphoria from nicotine, the excitement of winning in gambling) and negative reinforcement (e.g., avoiding withdrawal symptoms, escaping stress/loneliness) make the behaviour more likely to be repeated.

Treatments like aversion therapy and covert sensitisation, though rooted in classical conditioning, also apply principles of consequence to reduce undesirable behaviours and have shown effectiveness. - Other Applications: It also underpins classroom management techniques. The very design of social media apps and gambling systems use variable ratio reinforcement to drive compulsive engagement and make behaviour resistant to extinction, demonstrating the power of operant conditioning in influencing behaviour.

- Behaviour Modification: One of its most significant applications is in behaviour modification, especially in institutions like schools, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals.

-

Clear Explanatory Power Operant conditioning provides a clear and straightforward explanation of how behaviour is shaped and maintained by its consequences.

It distinguishes between reinforcement (positive and negative) which increases the likelihood of a behaviour, and punishment (positive and negative) which decreases it.

This mechanistic view allows for predictable patterns of behaviour based on changing contingencies, leading to the discovery of “schedules of reinforcement”.

It effectively explains the maintenance of responses, distinguishing itself from classical conditioning, which primarily explains the acquisition of responses. -

Pliable View of Human Behaviour The behaviourist approach suggests that humans are pliable, meaning abnormal behaviours are acquired through learning and can therefore be “unacquired” or treated.

This offers hope for individuals suffering from conditions like phobias (which are maintained by negative reinforcement, e.g., avoiding the feared stimulus reduces anxiety) and other problematic behaviours, by providing techniques to change these learned responses.

Limitations of Operant Conditioning:

-

Reductionist and Oversimplistic Operant conditioning is often criticised for being reductionist, as it attempts to explain complex human and animal behaviour by breaking it down into simple stimulus-response (S-R) links and focuses solely on observable behaviour.

This approach ignores internal mental processes (the “black box”), conscious choice, and potentially crucial biological factors.

Critics argue that complex human experiences like justice, culture, or self-sacrifice cannot be adequately explained by simple reinforcement.

By reducing behaviour to low-level components, it may overlook the complexity, context, and function of human behaviour. -

Hard Environmental Determinism The behaviourist approach, including operant conditioning, is rooted in a hard deterministic view.

It suggests that virtually all behaviour is determined by past conditioning experiences and environmental factors. Skinner famously argued that free will is an illusion, stating that everything we do is the sum total of our reinforcement history.

This deterministic stance implies individuals have little to no free will or personal responsibility, which can be controversial and has implications for legal and moral accountability.

Critics argue it removes personal responsibility as behaviour is seen as shaped entirely by the environment. -

Problematic Generalisability from Animal Research A significant amount of the research supporting operant conditioning, particularly B.F. Skinner’s work, was conducted on animals like rats and pigeons in highly controlled ‘Skinner Boxes’.

This raises concerns about the extent to which these findings can be generalised to complex human behaviour, which involves more intricate cognition, emotions, and social/cultural forces not fully accounted for in animal models.

While conditioning can be observed in most species, there are genetic influences on what different species can and cannot learn, which reflect their different evolutionary histories. -

Ethical Concerns in Research The animal studies conducted to demonstrate operant conditioning often involved exposing animals to stressful or harmful conditions, such as electric shocks in Skinner’s box.

These practices raise significant ethical concerns and are considered cruel by modern standards. Critics also argue that applying these ideas to control human behaviour can be manipulative, citing examples like social media’s use of ‘likes’ to increase engagement or gambling companies using variable ratio reinforcement to promote compulsive behaviour. -

Artificiality and Lack of Ecological Validity Many operant conditioning experiments are conducted in highly controlled laboratory settings (e.g., Skinner Box).

While this allows for strict variable control and objective data collection, it can create artificial conditions that may not accurately reflect real-world contexts. This can limit the ecological validity and generalisability of the findings to everyday life. -

Biological Constraints and Preparedness Operant conditioning struggles to explain why certain associations are learned more easily than others, or why some behaviours are difficult or impossible to condition.

Research on “biological constraints” and “preparedness” (e.g., Breland and Breland’s work with raccoons) challenges the idea that any behaviour can be conditioned. Organisms have biological predispositions that influence what they can learn, meaning the “laws of learning” may apply only to a restricted range of behaviours.

For example, a learning theory explanation for addiction “does not explain why men and women show some differences” or “why many people start smoking but do not become addicted,” suggesting other factors are involved. -

Incomplete Explanation for Initiation (e.g., Addiction) While operant conditioning is effective at explaining how behaviours are maintained (e.g., why smoking continues after initiation due to positive and negative reinforcement, or why gambling persists), it often struggles to explain how behaviours are initiated in the first place.

For instance, it “cannot explain how people start gambling”. This suggests that other factors, such as social learning (e.g., observing others), might be more relevant for the initial acquisition of complex behaviours. -

Neglect of Internal Mental Processes / Cognitive Elements Traditional operant behaviourism purposely avoids the study of mental states and internal processes, considering them a “black box” unsuitable for scientific investigation because they cannot be directly observed or measured.

However, cognitive psychologists argue that internal processes should be studied to fully understand learning.

Tolman, for example, argued that learning involves more than just mechanistic stimulus-response associations; he suggested that organisms learn ‘expectancies’ or that stimuli become ‘reliable predictors’.

The “cognitive revolution” emerged partly from the recognition that a purely mechanistic view of learning was too simplistic.

Social Learning Theory

Social Learning Theory (SLT) was developed by Albert Bandura in 1961 (Julian Rotter also invented the term in 1947).

SLT builds on behaviourist principles but offers a more realistic and comprehensive approach to learning by including cognitive processes.

Bandura agreed with behaviourism that behaviour is learned through experience and environmental influence, but argued that much of our learning happens indirectly through observing other people, not just through direct reinforcement or punishment.

SLT is considered a “bridge” between behaviourism and cognitive psychology because it acknowledges the role of mental factors in learning, not just stimulus and response.

It is firmly on the nurture side of the nature-nurture debate, emphasizing learned behaviour through observation and imitation.

- Imitation: The act of copying someone else’s behaviour. Bandura argued that some behaviours are too complex to be explained simply through classical or operant conditioning.

- Modelling: The demonstration of a behaviour by someone who serves as a “model”. Imitation is more likely if the model is positively reinforced.

- Identification: Imitation is more likely to occur if we identify with the model, meaning we perceive them as sharing similar characteristics with us (e.g., similar age, gender, social status).

- Vicarious Reinforcement: This is a key concept where learning occurs through observing someone else being rewarded or punished for a behaviour, rather than experiencing the reinforcement directly.

If an observer sees a model’s behaviour being rewarded, they are more likely to imitate it; conversely, if they see it punished, they are less likely to copy it. Information about this vicarious reinforcement is stored as an expectancy of future outcomes.

The Role of Mediational Processes

Bandura emphasized that learning is not automatic.

He proposed the existence of mediational cognitive processes.

These are cognitive factors (our thoughts) that influence learning and come between the stimulus (observing a model’s behaviour) and the response (imitating that behaviour).

This distinguishes SLT from pure behaviourism, which saw individuals as passive responders. SLT suggests people are more active in the learning process.

Bandura identified four cognitive mediational processes:

- Attention: The individual must pay attention to the behaviour and its consequences, forming a mental representation of it.

- Retention: The observed behaviour must be stored in long-term memory, as imitation is not always immediate.

- Motor Reproduction: The individual must have the ability and skills to physically reproduce the observed behaviour.

- Motivation: The individual must be motivated to perform the behaviour, often due to the expectation of receiving the same positive reinforcement (vicarious reinforcement) that they observed the model receiving.

Bandura’s Research

Bandura conducted a series of famous Bobo Doll experiments (1961, 1963, 1965) to investigate if social behaviours, particularly aggression, could be acquired by observation and imitation.

In these studies, children observed an adult model behaving aggressively towards an inflatable Bobo doll (e.g., hitting it and shouting abuse).

Different groups saw the model either rewarded, punished, or with no consequence for their aggression.

When later observed alone with a Bobo doll, children who had seen the model rewarded were most likely to imitate the aggressive acts, supporting the concept of vicarious reinforcement.

Boys consistently showed more physical aggression than girls in these experiments, regardless of the experimental condition.

Applications (AO2)

This theory is used to explain the influence of the media on behavior. This has been used in court in the case of Jamie Bulger’s murder (1990).

The perpetrators, who were themselves, children, claimed that they had been influenced by the film Child Play 3. However, these children came from disturbed families where they might have witnessed real-life violence and social deprivation.

Strengths of Social Learning Theory:

- Scientific Rigour and Evidence: SLT uses well-controlled research methods, often lab experiments with matched pairs designs, allowing for cause-and-effect conclusions. Observations can have high inter-rater reliability, as seen in Bandura’s studies (e.g., 0.89). Bandura’s own studies provide strong support for SLT concepts.

- Acknowledges Cognitive Factors: It recognizes the importance of internal mediational processes, offering a more complete explanation of learning than pure behaviourism, which neglects cognitive aspects. It explains how new behaviours can be acquired without direct trial-and-error, through observing others’ experiences.

- Explains Cultural Differences and Changes: SLT principles can explain how behaviours, including gender-related behaviours, differ across cultures as children model culturally specific norms. It can also account for changes in gender roles over time as minority views are observed and imitated.

- Real-Life Applications: SLT has significant practical applications, such as influencing media guidelines (age ratings on films/games) due to the understanding that people imitate observed behaviours.

It’s used in public health campaigns to encourage positive behaviours (e.g., non-smoking). Therapists use modelling to help individuals overcome phobias or develop social skills.

Limitations of Social Learning Theory:

- Underestimates Biological Factors: SLT often under-emphasizes innate biological influences. For example, while Bandura attributed gender differences in aggression to social factors, robust gender differences might hint at biological factors (like hormones) playing a role, which SLT struggles to explain.

- Issues with Lab Studies: Many SLT studies, including Bandura’s, are lab-based, which may lead to demand characteristics. Children in the Bobo doll study might have behaved aggressively because they felt it was expected, raising questions about the mundane realism and external validity of the findings.

- Inferred Mediational Processes: The cognitive factors (mediational processes) are internal and inferred from behaviour, meaning they cannot be directly observed or measured. This can reduce the scientific credibility of the approach compared to strict behaviourism or biological psychology.

- Limited Explanation of Origin: SLT can explain how behaviours are learned and maintained but may not fully explain where the initial behaviour comes from.

Issues and debates (Behaviorism)

Nature vs. Nurture Debate

The nature-nurture debate centres on the relative contributions of genetic inheritance (nature) and environmental influences (nurture) to human behaviour.

- Behaviourist Stance (Nurture): Behaviourism firmly aligns with the nurture side of this debate. It proposes that humans are like “tabula rasa” (blank slates) at birth, meaning the mind comes into the world with no innate ideas.

All complex behaviour is believed to be learned from the environment through experience. For example, a phobia is seen as a learned association between a neutral stimulus and a frightening unconditioned stimulus. - Contrast and Nuance: While strongly emphasising nurture, even behaviourists acknowledge a minor role for nature. For instance, primary reinforcers like food and sex are considered biological in nature, and animals are born with these drives.

However, the main criticism is that behaviourism, like the biological approach, can be seen as overemphasizing one side of the debate and failing to explain how both nature and nurture are involved.

Modern psychology increasingly adopts an interactionist approach, suggesting that both biological predispositions and environmental triggers are required for many behaviours or disorders to develop.

Free Will vs. Determinism Debate

This debate explores the extent to which our thoughts and behaviour are influenced by forces beyond our conscious control (determinism) versus being the result of our own choices (free will).

- Behaviourist Stance (Environmental Determinism): The Behaviourist approach is strongly environmentally deterministic. It asserts that all behaviour is caused by external forces, specifically past experiences that have been conditioned through reinforcement and punishment.

Skinner famously suggested that free will is an illusion, arguing that everything we do is the sum total of our reinforcement history. This means that behaviour is viewed as predictable because it always has a cause. - Implications and Criticisms: This hard determinist stance has significant implications. It suggests that individuals have no real autonomy or responsibility for their actions, which can be controversial in areas like ethics and the legal system.

For example, an offender might argue their behaviour is not their fault if it’s determined by past conditioning. In contrast, the humanistic approach promotes free will and personal growth, arguing that individuals can choose to change their behaviour.

Holism vs. Reductionism Debate

This debate concerns whether it is best to understand human behaviour by reducing it to its simplest components (reductionism) or by viewing it as a whole integrated experience (holism).

- Behaviourist Stance (Environmental Reductionism): Behaviourism is inherently reductionist, specifically advocating for environmental (stimulus-response) reductionism. Behaviourists believe that complex behaviours can be explained by breaking them down into fundamental stimulus-response (S-R) links and simple conditioning processes.

For example, attachment is reduced to a stimulus-response association where an infant associates the caregiver (conditioned stimulus) with the pleasure of food (unconditioned stimulus). - Scientific Credibility vs. Loss of Meaning: This reductionist approach is a strength for behaviourism’s scientific credibility, as it allows for controlled experimental research where variables can be isolated and measured objectively.

However, critics argue that reducing complex human behaviour to simple S-R chains overlooks internal mental processes and the richness of human experience, leading to a loss of meaning.

Humanists, in contrast, reject attempts to break down behaviour into smaller components, arguing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Idiographic vs. Nomothetic Debate

This debate concerns whether psychology should focus on the unique experiences of individuals (idiographic) or seek to establish general laws of behaviour that apply to everyone (nomothetic).

- Behaviourist Stance (Nomothetic): Behaviourism takes a strongly nomothetic approach. Its main aim is to produce general laws of human behaviour by studying large numbers of people and using quantitative methods.

Pavlov’s research, for instance, involved laboratory experiments to establish general principles of how behaviour can be learned through association. Skinner’s research on operant conditioning similarly sought to establish universal laws of learning based on controlled animal experiments. - Strengths and Limitations: This approach aligns with the scientific emphasis on causal explanations and allows for the prediction and control of behaviour, leading to practical applications like behaviour modification techniques.

However, critics argue that such general laws might overlook the unique complexity of individual human experience.

Ethical Implications and Socially Sensitive Research

Ethical implications consider the impact or consequences of psychological research or theory on the rights of participants and others in the wider context, while socially sensitive research has potential implications or consequences for certain groups.

- Ethical Concerns in Behaviourist Research: Behaviourist research, especially early studies, has been heavily criticised for its ethical issues.

- Animal Studies: Much of the supporting evidence for behaviourism comes from animal experiments, such as Skinner’s use of rats receiving electric shocks. These practices raise significant ethical concerns regarding animal welfare and might be seen as cruel.

- Human Studies: The most notable example is Watson and Rayner’s “Little Albert” study, where a baby was deliberately conditioned to fear white, fluffy objects through the pairing of a neutral stimulus with a loud, frightening noise. This caused extreme distress to the baby and would be considered highly unethical by modern standards, demonstrating a “long-running theme” of dubious ethics in some behaviourist human studies. These studies are rarely, if ever, replicated today due to strict ethical guidelines.

- Generalisability Issues: Beyond ethics, the reliance on animal studies raises questions about the generalisability of findings to human behaviour, as humans have more complex cognition and emotions not accounted for in basic conditioning models.

Cognitive Approach

The cognitive approach: the study of internal mental processes, the role of schema, the use of models to explain and make inferences about mental processes.

The cognitive approach is a significant perspective in psychology that emerged around the 1960s.

It focuses on how our internal mental processes influence our behaviour.

Unlike behaviourists who argued that mental processes couldn’t be studied scientifically because they aren’t directly observable, cognitive psychologists believe these private processes can and should be investigated scientifically.

Assumptions (AO1)

- The main assumption of the cognitive approach is that information received from our senses is processed by the brain and that this processing directs how we behave.

- These internal mental processes cannot be observed directly, but we can infer what a person is thinking based on how they act.

Internal Mental Processes and Inference

Internal mental processes refer to the private actions or operations of the mind that come between a stimulus and a response.

These include crucial functions such as perception, attention, memory, language, and problem-solving. Since these processes are “private” and cannot be directly observed, cognitive psychologists study them indirectly.

They do this by making inferences about what is happening inside people’s minds based on their observable behaviour.

An inference is a conclusion drawn about how mental processes work, which cannot be directly seen, by making assumptions based on observable behaviour.

While this reliance on inference can be criticised for not being fully objective and potentially mistaken, it is the only way to study these internal mental states.

Many inferences made about internal mental processes, such as memory, are supported by later studies, which increases confidence in their validity.

The Role of Schema

A central concept in the cognitive approach is the schema.

Schemas are defined as organised units of knowledge or mental frameworks of beliefs and expectations that individuals develop through experience.

They act as “packets of information” that help us organise and interpret incoming information quickly and effectively.

How Schemas Function:

- Schemas help us make sense of situations and make life predictable by guiding our expectations. For example, a schema for a restaurant helps you understand the protocol (sit down, wait to be served).

- They prevent us from being overwhelmed by the vast amount of information we perceive in our environment.

- When new information is consistent with an existing schema, it’s added, making the schema more detailed. If new information is inconsistent, we accommodate by changing the existing schema or forming a new one.

Impact of Schemas (Positive and Negative):

- Usefulness: Schemas allow us to process stimuli in the simplest and most economical way, helping us predict what will happen based on past experiences. This efficiency is crucial for navigating the world without excessive overthinking.

- Potential Downsides: Schemas can sometimes distort our interpretation of sensory information, leading to perceptual errors or inaccurate memories, especially in eyewitness testimony. When we recall events, memories are reconstructed and can be influenced by our schemas. This understanding has been applied to improve police interviews through the cognitive interview technique.

- Mental Health: Schemas can also impact mental health. Negative self-schemas, where individuals view themselves negatively, contribute to theories of depression (e.g., Beck’s cognitive triad). These negative schemas can create cognitive biases and distorted interpretations of life events, reinforcing depressive symptoms. Cognitive psychologists also believe that gender schemas, organised sets of information about gender-appropriate behaviour, are learned by children and can influence their own behaviour and expectations of others.

The Use of Models (Theoretical and Computer)

Cognitive psychologists frequently use models to explain and represent how mental processes work.

These models are simplified representations, often showing the stages of a particular mental process, since mental processes cannot be directly observed.

They allow psychologists to provide testable theories about mental processes that can be studied scientifically.

- Theoretical Models: These are flowchart-like representations showing the flow of information through cognitive systems. A prominent example is the Multi-Store Model of Memory by Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968).

This model proposes multiple, separate stores for sensory, short-term, and long-term memory, with information flowing linearly through them.

Another example is the Working Memory Model by Baddeley and Hitch (1974), which refined the understanding of short-term memory as an active processor with multiple components (e.g., central executive, phonological loop, visuo-spatial sketchpad). - Computer Models (Computer Analogy): The cognitive approach views mental processes as a form of information processing, often comparing the mind’s operation to that of a computer. This analogy suggests that information is input (through senses), processed (by the brain), stored (in memory), and then retrieved or output.

Criticisms of the Computer Analogy:

This comparison can be seen as overly simplistic and lead to “machine reductionism”.

Critics argue that the human brain is far more complex than a CPU, and the model fails to account for crucial aspects like consciousness, emotions, and irrationality, which significantly affect human thought and behaviour.

Human memory, for instance, is flawed and reconstructive, unlike the perfect recall assumed by computer models.

Strengths of the Cognitive Approach

-

Scientific Rigour and Objective Methods The cognitive approach is highly regarded for its commitment to scientific methods. It primarily employs controlled laboratory experiments with large samples, which allows for objective measurement and replication of findings.

This rigorous methodology enhances the reliability and credibility of cognitive theories and has helped psychology gain status as a robust science. By focusing on measurable variables and establishing cause-and-effect relationships, it allows for testable theories about mental processes.

The approach also adopts a nomothetic stance, aiming to establish general laws and theories that apply to all people. -

Wide Range of Practical Applications A significant strength of the cognitive approach is its extensive practical applications, which have had a real-world impact.

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): This approach has greatly influenced the development of effective treatments for mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

CBT helps clients identify and challenge irrational thoughts and negative schemas, empowering them to change their thinking patterns and improve coping strategies.

It is often seen as a favourable alternative to drug treatments due to a lack of side effects and a focus on patient empowerment. - Cognitive Interview (CI): Understanding how schemas can distort memory has led to the development of the cognitive interview, a police technique designed to improve the accuracy of eyewitness testimony.

By encouraging witnesses to reinstate context, report everything, recall in reverse order, or change perspective, the CI can reduce the influence of schemas and lead to more reliable evidence in criminal investigations. - Artificial Intelligence (AI): Cognitive psychology has contributed to the field of AI and the development of “thinking machines” or robots, revolutionising various aspects of life.

- Cognitive Neuroscience: Advances in cognitive neuroscience, enabled by brain scanning technologies, have practical benefits for diagnosing and treating memory-related conditions and mental health disorders like schizophrenia [B4, 253, 331, 594].

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): This approach has greatly influenced the development of effective treatments for mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

-

Focus on Internal Mental Processes The cognitive approach filled a significant gap in psychological study by explicitly investigating internal mental processes such as memory, perception, and thinking, which behaviourists had largely neglected because they are not directly observable.

This allowed psychologists to gain a deeper understanding of complex human behaviours that cannot be explained solely by external stimuli and responses.

The approach acknowledges that human understanding of the world, including concepts like gender, develops through active cognitive processing. -

Soft Determinism: The cognitive approach adopts a position of “soft determinism,” a middle ground between hard determinism and free will.

It recognizes that our cognitive system operates within the limits of our knowledge and experiences (e.g., schemas formed through past experiences), but also asserts that we have the freedom to think, choose, and process information before responding to a stimulus.

This perspective allows for personal control over actions, which is a core principle of CBT, enabling individuals to change their thought patterns. -

Studies Humans for Generalizability Unlike much of the behaviourist research, which was conducted on animals, the cognitive approach primarily focuses on human participants and human cognitive processes (like memory, perception, and problem-solving).

This makes its findings more directly applicable and generalizable to human behaviour, avoiding the limitations of extrapolating from animal studies. -

Interactionist View (Nature-Nurture) The cognitive approach often takes an interactionist stance on the nature-nurture debate.

It acknowledges that human behaviour is influenced by both learning and experience (nurture), which contribute to the formation of schemas and mental processes, and innate capacities of the brain (nature), such as basic information processing abilities or language acquisition.

This balanced view recognizes the interplay between biological predispositions and environmental influences.

Limitations of the Cognitive Approach

-

Machine Reductionism and Oversimplification of Human Experience A common criticism of the cognitive approach is its “machine reductionism,” which often compares the human mind to a computer, reducing complex mental processes to simplistic input, storage, and output systems.

This mechanistic view is criticized for failing to account for crucial aspects of human experience, such as emotions, consciousness, and irrationality, which significantly influence thought and behaviour.

For example, emotions like fear or anxiety can profoundly affect memory, especially in high-stress situations, a factor that the computer analogy struggles to explain.

Critics argue that reducing human behaviour to machine-like processes loses what it means to be human and does not fully explain complex human actions. -

Lack of Ecological Validity and Artificiality of Research Cognitive psychology is sometimes criticized for being too abstract and theoretical.

Its reliance on highly controlled laboratory experiments, often using artificial stimuli (e.g., word lists for memory tests), means that research findings may lack mundane realism and ecological validity.

The tasks performed in these experiments are often very different from how people use their cognitive processes in everyday life, which limits the generalizability of the findings beyond the laboratory setting.

For example, the capacity of short-term memory might appear different in a real-life scenario compared to a lab experiment using random numbers. -

Problems with Inference and Subjectivity Since internal mental processes cannot be directly observed, cognitive psychologists must make inferences about them based on observable behaviour.

This reliance on inference can be problematic because it introduces an element of subjective interpretation, potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions about what is truly happening in the mind.

While many inferences are later supported by further studies, the initial reliance on non-observable data means the approach is not entirely objective, unlike the strict objectivity advocated by behaviourists. -

Oversimplification and Limited Scope The cognitive approach sometimes oversimplifies complex phenomena by focusing on individual mental processes in isolation, rather than explaining how different mental processes work together or how they interact with broader factors.

For instance, when studying memory, it might isolate it from other cognitive processes, which are typically used simultaneously in real-life situations, thereby lacking validity in capturing the holistic nature of human cognition. -

Neglect of Underlying Causes and Other Influences A significant limitation, particularly in areas like psychopathology, is that the cognitive approach often describes how cognitive deficits or biases contribute to a condition but does not adequately explain their underlying causes.

For example, in schizophrenia, it explains cognitive impairments but doesn’t fully account for their origins, which may be biological (e.g., structural brain abnormalities or neurotransmitter imbalances).

This can lead to an incomplete understanding of complex disorders, suggesting that other approaches (like the biological or interactionist perspectives) are needed for a comprehensive explanation. -

Vague Central Executive (in Working Memory Model) Within the prominent Working Memory Model, a key limitation is that “little is known about how the central executive works”.

Its nature is considered vague and untestable, with evidence from brain studies sometimes suggesting it is not a unitary component. This ambiguity undermines a crucial part of the model’s structure.

Issues and debates (Cognitive)

Scientific Credibility and Methodology

The cognitive approach is often praised for its scientific methodology.

It emerged in the 1960s as a response to the behaviourist approach, which focused only on observable behaviour and neglected mental processes.

- Highly Controlled Methods: The cognitive approach employs highly controlled and rigorous methods of study, often using laboratory experiments to produce reliable, objective data. This commitment to objective measurement and replicability enhances its scientific credibility.

- Emphasis on Empirical Evidence: It contributes to psychology’s status as a rigorous science by emphasising empirical evidence.

- Integration with Neuroscience: The emergence of cognitive neuroscience, which scientifically studies the influence of brain structures on mental processes, has further enhanced its scientific standing by combining cognitive processes with biological structures and brain scanning technology.

Reductionism vs. Holism

- Reductionist Criticism: The cognitive approach is often criticised for being reductionist, particularly through its use of the “computer analogy” and viewing human beings as information processing “machines”.

This mechanistic view can be seen as oversimplifying human behaviour by reducing mental processes to input, storage, and output systems.

It is argued that this approach ignores the role of emotions, motivation, and broader social factors, which significantly influence human thought and behaviour. - Oversimplification: Critics argue that the cognitive approach can be oversimplistic by focusing on individual mental processes and not fully explaining how different processes work together.

- Interactionist Perspective: While not explicitly holistic in itself, the cognitive approach is sometimes contrasted with more holistic or interactionist views, such as the diathesis-stress model in schizophrenia, which suggests that a combination of biological and environmental factors (rather than just cognitive ones) is necessary for a complete explanation.

Free Will vs. Determinism

- Soft Determinism: The cognitive approach is generally considered to adopt a position of “soft determinism”.

It acknowledges that our cognitive system operates within the limits of what we know (e.g., our schemas shaped by past experience), but it also suggests that individuals have the freedom to think before responding to a stimulus.

This is seen as a more reasonable, “interactionist” middle ground compared to the “hard determinism” of some other approaches. - Implication of Choice in Therapy: The success of cognitive therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) implies an element of free will, as they are based on the idea that individuals can actively challenge and change their irrational thoughts and behaviours.

Nature vs. Nurture

- Interactionist View: The cognitive approach takes an interactionist stance on the nature-nurture debate.

It recognises that behaviour is influenced by both learning and experience (nurture), which shapes our schemas and thinking patterns, but also by some of our brain’s innate capacities as information processors (nature), such as language acquisition.

Cognitive neuroscience, by linking mental processes to brain structures, further exemplifies this interactionist perspective, showing how biological predispositions and environmental experiences together shape cognition.

Biological Approach

The biological approach: the genetic basis of behaviour: genotype, phenotype and evolution. Influence of biological structures and neurochemistry on behaviour. Cognitive neuroscience.

Assumptions

The Biological Approach in psychology assumes that human behaviour can be explained and predicted using biological processes.

This perspective posits that everything psychological is fundamentally biological.

It gained prominence with technological advancements in the 1980s, which allowed for the study of genetics and brain chemicals.

Genetic Basis of Behaviour

The biological approach assumes that psychological traits, such as intelligence, personality, and even mental illness, can be inherited from parents, just like physical traits.

Genes are segments of DNA found on chromosomes that contain genetic information, coding for both physical and psychological characteristics.

The genetic explanation suggests that psychological and behavioural abnormalities have biological causes.

For instance, schizophrenia is seen as transmitted through genes passed down from families, with the risk increasing with closer genetic relatedness.

Similarly, a genetic vulnerability has been evidenced for conditions like Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Genotype and phenotype

- Genotype refers to the specific genetic makeup of an individual, containing the inherited information from their parents. It includes all the genetic information about an organism, even characteristics that are not visually expressed. Genotypes can only be determined by biological tests.

- Phenotype describes the observable expression of the genotype, which is also influenced by environmental factors. For example, a person might inherit a genetic risk for dementia (genotype), but lifestyle factors like diet or lack of sleep can influence whether the condition (phenotype) actually develops. Phenotypes can be determined by simple observation.

The Interplay of Genotype and Phenotype

The relationship between genotype and phenotype highlights the nature-nurture debate, illustrating that behaviour and characteristics are not solely determined by genes but also by environmental influences.

- Dementia: An individual might inherit a genetic risk for dementia (their genotype), but whether the condition (the phenotype) actually develops can be influenced by lifestyle factors such as diet or lack of sleep.

- Twin Studies: When comparing identical twins, who share the same genotype, differences in their observable traits (phenotypes) can be attributed to environmental influences.

For example, if two identical twins, Ellie and Lucy, have different scores on an intelligence test, it suggests that despite their identical genotypes, their phenotypes were influenced by environmental factors like different teachers or learning experiences.

Similarly, if Lily and Jemima, identical twins, have different netball skills or skin clarity, it’s due to environmental factors like practice, diet, or sun exposure, even though their genotypes are the same. - Phenylketonuria (PKU): This genetic disorder (genotype) affects the body’s ability to break down phenylalanine, found in certain foods. If an individual with PKU follows a strict diet (environmental factor) to avoid this substance, their phenotype will be normal intelligence and behaviour.

However, if they consume foods containing phenylalanine, it accumulates in the brain, leading to severe learning difficulties and behavioural problems (a different phenotype).

This clearly demonstrates how the presence of particular genes can lead to different outcomes depending on the social environment, showcasing the interaction between nature and nurture.

Evolution

Evolution refers to the gradual change in inherited traits of a species over many generations, occurring through adaptation.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, described in “On the Origin of Species” (1859), is central to this.

This theory suggests that characteristics or behaviours that enhance an individual’s chances of survival and successful reproduction are more likely to be passed on to future generations and become more common within a population.

Traits that are less adaptive tend to be “weeded out” (survival of the fittest).

Evolutionary psychology, a subfield, applies these principles to mental and psychological traits, viewing them as adaptations that increased survival.

For example, the rooting reflex in infants aids breastfeeding and survival, suggesting an adaptive, inherited behaviour.

Aggressive behaviour, in early hunter-gatherer societies, might have been beneficial for protecting families, hunting, and competing for mates, leading to aggressive traits being passed on.

The biological approach uses animal studies partly due to this evolutionary view, assuming similarities between animal and human biological makeup.

Influence of Biological Structures on Behaviour

The biological approach considers that interactions between regions of the brain help control different functions, which are significant in determining our actions.

Biological structures include the brain, the nervous system, and the endocrine system.

The Brain

The brain is often divided into two hemispheres, each subdivided into different lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal), and each part is thought to be responsible for specific functions.

This concept is known as localisation of function.

For instance, the frontal lobe is involved in rational decision-making and personality, the occipital lobe in visual processing, the parietal lobe in sensory processing, and the temporal lobe in hearing and speech.

Deeper brain structures like the hippocampus are thought to play a significant role in memory and learning. Evidence for the influence of brain structures comes from case studies of individuals with brain damage.

A famous example is Phineas Gage, a railway worker from the mid-1800s, whose personality reportedly changed drastically after an iron rod pierced his frontal lobe.

This case supported the idea of localisation of brain function. Abnormalities in brain structure, such as reduced grey matter in the prefrontal cortex, have also been linked to criminal behaviour.

Other Biological Structures

The nervous system coordinates senses, actions, and behaviour, allowing individuals to respond to their environment.

It includes the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system (somatic and autonomic).

Electrical impulses are a key means of internal communication, travelling through neurons (nerve cells) and the nervous system to direct behaviour.

The endocrine system is a body-wide system of glands that influences behaviour by releasing chemical messengers called hormones directly into the bloodstream.

Hormones can have short-term effects, like adrenaline in the “fight or flight” response, and long-term effects, such as sex hormones like testosterone and oestrogen influencing sexually dimorphic features and aggression.

Influence of Neurochemistry on Behaviour

Neurochemistry refers to the chemical processes within the brain, particularly involving neurotransmitters, which are chemical messengers that transmit information between neurons at synapses.

The biological approach posits that these chemical processes in the brain underpin mental states.

Imbalances in neurotransmitter levels can lead to changes in mood or behaviour and are often associated with abnormal behaviour or mental disorders.

- Serotonin: Low levels of serotonin have been linked to depression and OCD. Some research suggests that a specific gene (SERT) is implicated in the efficiency of serotonin transport.

- Dopamine: High levels of dopamine have been linked to schizophrenia and OCD. The dopamine hypothesis suggests that excess dopamine in brain regions can lead to positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

The understanding of neurochemical processes has led to the development of psychoactive drugs, such as SSRIs for depression and OCD, which aim to correct these imbalances and manage symptoms.

Applications (AO3)

- The understanding of the role of neurotransmitters has led to the development of drugs that are effective in the treatment of mental disorders such as schizophrenia and depression.

- This enables many of the sufferers to lead fairly normal lives.

- However, these drugs are not effective for all patients, and they can have serious side effects. They do not cure the disorders, and if the patients stop taking the drug, the symptoms reappear.

Cognitive Neuroscience

Cognitive neuroscience is a contemporary and rapidly developing area of psychology that emerged with advances in technology.

It represents the scientific study of the influence of brain structures and biological processes on mental processes.

It explicitly combines cognitive psychology with biological approaches to understand how brain structures influence mental processes.

Methods and Applications:

- The emergence of cognitive neuroscience is largely due to the development of advanced brain scanning techniques like fMRI and PET scans, which allow researchers to observe brain activity directly.

- This field aims to identify the neurological structures and chemical processes in the brain linked to internal mental processes.

- Examples include research showing different areas of the prefrontal cortex active for episodic versus semantic memories, and identifying specific brain areas linked to different types of memory. Such advances have practical benefits for diagnosing and treating memory-related conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and contribute to understanding mental health disorders like schizophrenia. For instance, research uses fMRI to compare brain functioning of schizophrenic and non-schizophrenic individuals to identify linked brain areas.

Strengths of the Biological Approach

Scientific Credibility and Research Methods:

- The biological approach is praised for its highly scientific research methods. It employs objective, highly controlled methods such as fMRI and PET scans, family and twin studies, and drug trials.

- These methods allow for accurate measurement of biological and neural processes, reducing bias. High control over variables in laboratory experiments allows for the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships and enhances replicability and reliability of findings. This scientific rigour has contributed to psychology’s status as a credible scientific discipline.

- For example, twin studies investigate concordance rates for traits like OCD, where a higher rate in monozygotic (identical) twins compared to dizygotic (non-identical) twins suggests a genetic influence.

Practical Applications and Treatments:

-

- Increased understanding of biochemical processes in the brain has led to the development of psychoactive drugs that treat serious mental illnesses like depression, OCD, and schizophrenia.

- These drugs have “revolutionised treatment for many” and allow sufferers to manage their condition and live more normal, fulfilling lives. For instance, SSRIs are used to increase serotonin levels in the brain to reduce OCD symptoms.

- The biological model of abnormality assumes psychological and behavioural abnormalities have biological causes, leading to biologically-based treatments.

Plausible Explanations:

-

- The approach provides plausible explanations for behaviour that are often backed up by empirical evidence. For example, the dopamine hypothesis suggests elevated dopamine levels are related to schizophrenia symptoms. It also considers evolutionary history and instinctive patterns.

Limitations of the Biological Approach

Reductionism:

- The biological approach is criticised for being reductionist. It reduces complex behaviour, thoughts, and emotions to low-level biological mechanisms such as genes, neurochemistry (e.g., neurotransmitter imbalances like serotonin, dopamine), or specific brain structures.

- This “biological reductionism” overlooks the complexity, context, and function of behaviour, and may ignore psychological, social, and cultural factors. For instance, reducing psychological illness to a single biological cause may overlook a variety of involved factors.

- A more holistic or interactionist approach, such as the diathesis-stress model, is often argued to provide a more complete understanding by considering the interaction of biological and environmental factors.

Determinism:

- The biological approach is criticised for being deterministic, suggesting that human behaviour is governed by internal, biological causes over which individuals have no control.

- This view implies that people have no free will and are unable to change their behaviour, which can be seen as pessimistic and disempowering, particularly for those with mental health conditions.

- It has implications for moral responsibility and the legal system, as it suggests individuals might not be accountable for their actions if they are determined by uncontrollable biological factors.

Difficulty Separating Nature and Nurture (Confounding Variables):

- While twin and family studies show genetic similarities, they have an “important confounding variable”: identical twins and family members are also exposed to similar environmental conditions.

- This means that observed similarities in behaviour could be interpreted as supporting nurture rather than nature, making it difficult to disentangle the relative contributions of genes and environment. For example, differences in intelligence or physical traits between identical twins can be attributed to environmental influences, even with identical genotypes.

- The approach underemphasizes environmental influences compared to other approaches.

Generalizability Issues (Animal and Case Studies):

- Much of the research in the biological approach, especially concerning biological mechanisms, is conducted on animals. However, human behaviour is considered more complex, involving aspects like emotion, consciousness, language, and morality, making it difficult to generalize findings from animals to humans.

- Similarly, relying on case studies (e.g., Phineas Gage) means findings are based on unique individuals and circumstances, limiting generalizability to the wider population.

Problems with Cause and Effect (Treatment Fallacy):

- The biological approach often infers causality from associations, which can be problematic. For example, if a drug reduces the symptoms of a mental disorder (e.g., SSRIs reducing OCD symptoms), it is often assumed that the neurochemical targeted by the drug caused the disorder.

- This is known as the “treatment fallacy”—just because taking paracetamol relieves a headache doesn’t mean the headache was caused by a lack of paracetamol. This suggests the approach claims to have discovered causes where only an association exists. Also, unusual neural activity could be a consequence of the disorder or medication rather than a cause.

Incomplete Explanations:

-

- The focus on biological factors can lead to other important variables being overlooked, resulting in an incomplete understanding of behaviour or psychological illness.

- For instance, it may ignore the role of mental processes, social factors, or early life experiences.

Issues and debates (Biological)

Free will Vs. determinism

It is strongly determinist as it views our behavior as caused entirely by biological factors over which we have no control.

Nature Vs. nurture

The biological approach is firmly on the nature side of the debate; however, it does recognize that our brain is a plastic organ that changes with experience in our social world, so it does not entirely deny the influence of nurture.

Holism Vs. reductionism

The biological approach is reductionist as it aims at explaining all behavior by the action of genetic or biochemical processes. It neglects the influence of factors such as early childhood experiences, conditioning, or cognitive processes.

Idiographic Vs. nomothetic

It is a nomothetic approach as it focuses on establishing laws and theories about the effects of physiological and biochemical processes that apply to all people.

Are the research methods used scientific?

The biological approach uses very scientific methods such as scans and biochemistry. Animals are often used in this approach as the approach assumes that humans are physiologically similar to animals.

Psychodynamic Approach

(A-level Only)

The psychodynamic approach: the role of the unconscious, the structure of personality, that is Id, Ego and Superego, defence mechanisms including repression, denial and displacement, psychosexual stages.

The psychodynamic approach, first developed by Sigmund Freud, is a major perspective in psychology that posits all behaviour can be explained by the inner conflicts of the mind.

It highlights the crucial role of the unconscious mind, the structure of personality, and the profound influence of childhood experiences on later life.

This approach sees human beings as driven by unconscious emotional drives.

Assumptions (AO1)

- The main assumption of the psychodynamic approach is that all behavior can be explained in terms of the inner conflicts of the mind.

- Freud highlights the role of the unconscious mind, the structure of personality, and the influence that childhood experiences have on later life.

- Freud believed that the unconscious mind determines most of our behavior and that we are motivated by unconscious emotional drives.

Role of the Unconscious

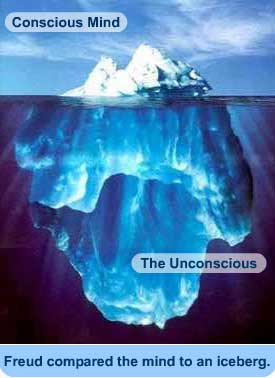

Freud famously compared the mind to an iceberg, with only a small portion visible above the surface.

- Conscious Mind: This is the tip of the iceberg, representing what we are currently aware of at any given time, including our ideas, decisions, and emotions.

- Pre-conscious Mind: Just below the surface, this part contains thoughts and memories that are not currently conscious but can be accessed with some effort, such as through dreams or “slips of the tongue” (Freudian slips).

- Unconscious Mind: This is the largest and most significant part, hidden beneath the surface. It’s not directly accessible to awareness but profoundly influences our conscious feelings and behaviours. The unconscious holds our biological drives and instincts, as well as upsetting or disturbing thoughts and memories repressed from consciousness.

- The conscious: this is the part we are aware of and can access without any effort. It contains part of the ego.

- The preconscious: this is a part of the mind that we cannot access without effort. It contains the ego and some of the superego.

- The unconscious: this part of the mind cannot be accessed without the help of a trained psychoanalyst. It contains the superego and the Id.

According to Freud, a primary role of the unconscious is to be the driving and motivating force behind our behaviour and personality.

It contains primal instincts like survival and sexual urges, and aggression, which control our behaviour. Another vital role is to protect the conscious self from anxiety, fear, trauma, and conflict.

Painful or traumatic memories, often from childhood, are pushed into the unconscious through psychological defence mechanisms.

Structure of Personality

Freud theorised that personality has a tripartite structure, meaning it’s composed of three parts: the Id, Ego, and Superego.

These three parts are in constant conflict, and the outcome of their interaction determines an individual’s behaviour.

Id (Pleasure Principle):

This is the innate and primal part of the personality, present entirely from birth and operating entirely unconsciously.

The Id demands instant gratification of its needs, driving individuals to act on basic urges and desires (like food, comfort, and sex) without considering consequences.

Freud referred to the psychic energy driving these instincts as libido. A dominant Id can lead to impulsive behaviour and a lack of self-control.

Ego (Reality Principle):

Developing around 1 to 3 years of age, the Ego functions on the reality principle.

It mediates the conflicts between the impulsive Id and the strict Superego.

The Ego helps individuals make decisions that are realistic and socially acceptable, balancing desires with what is right and possible in the real world.

It uses defence mechanisms to manage these conflicts.

Superego (Morality Principle):

This part of the personality develops around 3 to 5 years old, during the phallic psychosexual stage. It is primarily unconscious but influences conscious thoughts and acts as an individual’s conscience.

The Superego represents internalised moral standards and ideals derived from parents and society. When these rules are broken, the Superego causes feelings of guilt.

A healthy Superego is like a “kind but firm internal parent”.

Conversely, an over-harsh Superego can lead to excessive guilt, sometimes causing individuals to commit crimes to fulfil an unconscious desire for punishment.

A weak or underdeveloped Superego, due to poor parental relationships or a lack of identification with the same-sex parent, can result in the Id not being properly controlled, leading to criminal behaviour.

To be mentally healthy, the ego has to be able to balance the demands of the ego and the superego. If the superego is dominant, the individual might develop a neurosis, e.g., depression. If the ID is dominant, the individual might develop a psychosis, e.g., schizophrenia.

Defence Mechanisms

Defence mechanisms are psychological strategies employed by the unconscious mind to reduce anxiety generated by threats from unacceptable or negative impulses.

They are used by the Ego to manage the constant conflict between the Id and the Superego.

While they can offer temporary coping, they often involve a distortion of reality and are considered unhealthy as long-term solutions.

Three key defence mechanisms include:

Repression:

This involves forcing distressing memories, thoughts, or impulses out of the conscious mind and into the unconscious, where they are inaccessible.

For example, a child who experienced abuse might have no conscious recollection of these events but may struggle to form relationships later in life, driven by these unconscious, repressed issues.

Repression is entirely unconscious, unlike suppression, which is a conscious effort to forget something.

Denial:

This is when an individual refuses to acknowledge or accept some part of reality, whether internal or external.

An example is an alcoholic refusing to believe they have a problem despite negative consequences.

Displacement:

This mechanism involves redirecting a strong emotion (like anger) from its original, threatening target onto a more acceptable or substitute person or object.

For instance, someone angry at their boss might go home and shout at a family member or slam a door instead.

Displacement can also explain why some might commit lesser crimes (e.g., petty theft) instead of more serious ones they unconsciously wish to commit.

Psychosexual Stages

Freud believed that personality development occurs as individuals pass through a series of five psychosexual stages.

These stages emphasise the importance of libido (sexual energy) as the driving force in development, directed to different areas of the body at each stage.

Each stage presents an unconscious conflict that must be resolved for normal development to proceed to the next stage.

If a conflict is not resolved, an individual can become fixated at that stage, meaning the libido energy remains “stuck,” leading to dysfunctional behaviours or personality traits carried into adult life.

| Stage | Source of pleasure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Oral (0-1year) | Mouth – sucking, swallowing, etc. | If forceful feeding, deprivation, or early weaning occur, then fixation could lead to oral activities (e.g., smoking), dependency, and aggression. |

| Anal (1-3 years) | The anus – withholding or expelling feces. | If toilet training is too harsh or too lax, then fixation could lead to obsessiveness, tidiness, meanness, or to untidiness and generosity. |

| Phallic (3-5 years) | The penis or clitoris – masturbation. | If an abnormal family set-up leads to an unusual relationship with the mother/father, then fixation could lead to Vanity, self-obsession, sexual anxiety, inadequacy, Inferiority, envy, |

| Latent (5-puberty) | Sexual drives are repressed. | Fixation does not happen at this stage. |

| Genital (puberty-death) | The genitals. The adult derives pleasure from masturbation and sexual intercourse. | Fixation at this stage should occur in a mentally healthy adult. |

For more information on psychosexual stages, click here.

Applications (AO3)

- The psychodynamic approach has given rise to one of the first “talking cures, “psychoanalysis, on which many psychological therapies are now based. Psychoanalysis is rarely used now in its original form, but it is still used in a shorter version in some cases.

- This approach can be used to explain mental disorders such as depression and schizophrenia, although these explanations are rarely used by mainstream psychology. One of the very influential concepts put forward by Freud is the lasting importance of childhood on later life and development.

- Psychoanalysis has been used as a form of literary criticism in literature such as Hamlet, where repressed messages are hidden beneath the surface of the text. Interpretation allows us to delve into the character’s mind – It can be used to explain behavior outside psychology.

Strengths of the Psychodynamic Approach