An amygdala hijack describes a very fast, intense emotional reaction that is disproportionate to the situation — one in which the brain’s emotional machinery (the amygdala) essentially “takes over” before our thinking brain can intervene.

The result often involves impulsive or reflexive behaviour — for instance snapping in anger, freezing in fear, or shutting down emotionally — that we may regret later.

Key Takeaways

- Amygdala hijack is an emotional overreaction response to stress. This activates the fight-or-flight response and disables one’s rational, reasoned response.

- Amygdala hijack can happen to anyone and is usually triggered by something, causing the amygdala to ‘disable’ the frontal lobes and take control of your emotional responses.

- Sometimes we have suppressed emotions that suddenly become prominent when triggered by past memories, which then results in activation of the fight or flight response.

- This triggering can result in inappropriate or irrational behavior, such as shouting at someone you care about.

- After the amygdala hijack, we may feel emotions of shame, embarrassment, or guilt.

Where the term came from

Psychologist Daniel Goleman coined the phrase in his 1995 book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ.

Goleman used the term to illustrate how, under strong emotional arousal, the emotional brain can overwhelm the rational brain, bypassing the slower, more considered processing in the neocortex.

The amygdala’s role in emotions

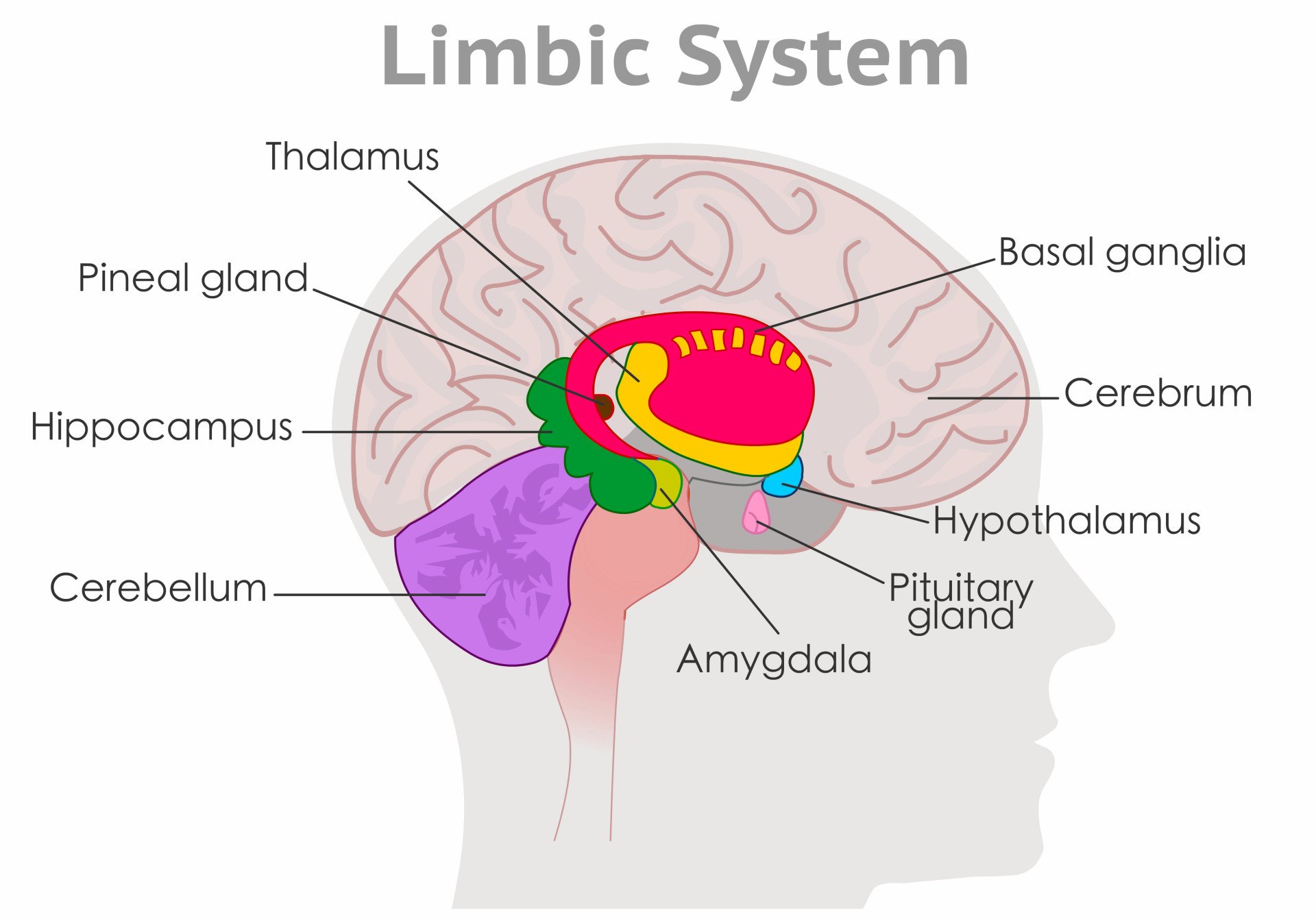

The amygdala is an almond-shaped structure deep in each hemisphere of the brain, part of the limbic system, which helps evaluate sensory input for emotional significance (especially threats).

When it detects a match to a threatening or emotionally charged pattern (based on memory), it can trigger the fight-flight (or freeze) response very quickly, often before the frontal lobes have had time to assess whether the threat is real.

In such cases, the amygdala “hijacks” control of behaviour by activating stress pathways (via the HPA axis), rerouting processing away from the thinking parts of the brain.

Amygdala Hijack Signs

Emotional signs

When an amygdala hijack occurs, the emotional response tends to be sudden, intense, and disproportionate to the trigger.

Typical emotional signs include:

After the fact, individuals often report regret, embarrassment, or guilt for how they responded.

Because the hijack bypasses slower, rational processing, the reaction can feel almost automatic, leaving the person surprised at their own behavior when they “come to.”

Physical signs

The body’s fight-or-flight system is activated during an amygdala hijack, producing a cascade of physical symptoms.

Common signs include:

- A racing heart

- Sweaty or clammy skin

- Dilated pupils

- Goosebumps

- Trembling or shaking

- Fast shallow breathing

- Tense muscles

Sometimes people also feel a sense of being unable to think clearly (a narrowing of attention or tunnel vision), as working memory and rational thought temporarily shut down.

Everyday examples

In everyday life, amygdala hijacks often show up in situations of interpersonal stress or perceived threat (even if not life-threatening).

For example:

- Someone might snap at a loved one over a small misunderstanding or criticism, reacting more harshly than the situation warrants.

- In traffic or driving, a minor frustration (e.g., someone cutting in) might trigger road rage, with swearing, honking, or aggressive gestures.

- In contexts like public speaking or performance, sudden anxiety or panic may arise, causing freezing, stammering, or an emotional shut-down before calm thinking returns.

Amygdala Hijack Causes

The Brain’s “Fast Track” Response – Thalamus → Amygdala Bypassing Logic

Amygdala hijacks occur because the brain has a rapid “low road” pathway: sensory inputs go from the thalamus directly to the amygdala—its emotional center—before reaching the cortex.

When the amygdala detects a threat, it quickly activates the stress response through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This fast reaction bypasses the cortex, which usually handles slower, rational thinking.

This triggers a fight–flight (or freeze) response in milliseconds—often before conscious awareness—resulting in reflexive, emotional reactions rather than rational responses.

Common Triggers

Amygdala hijacks aren’t only sparked by life-threatening events. In everyday life, several modern stressors can set them off:

- Work pressure and deadlines – feeling overwhelmed by tasks or performance expectations can activate the stress response.

- Criticism and rejection – harsh feedback from a boss, teacher, or partner may be perceived as a threat, prompting an outsized reaction.

- Conflict and arguments – disagreements at home, school, or work can trigger strong emotional responses, especially if they feel personal.

- Social anxiety and judgment – fear of embarrassment, public speaking, or being evaluated by others often hijacks the amygdala.

- Everyday frustrations – small irritations like traffic jams or being interrupted may accumulate into sudden emotional outbursts.

These triggers highlight that the amygdala doesn’t differentiate between physical danger and social or emotional stress.

Even minor stressors can feel like threats to the brain, causing reflexive emotional reactions before rational thought can intervene.

Mental Health and Trauma Links

The amygdala is strongly implicated in several mental health conditions, particularly anxiety disorders.

Hyperactivation has been observed in social anxiety disorder and specific phobias, where individuals show heightened, irrational reactions to feared situations (Etkin, Tor, & Wager, 2007).

Similar patterns occur in panic disorder, PTSD, and OCD, all of which involve stronger emotional responses and difficulties with regulation.

Past trauma also sensitizes the amygdala. Research shows that early life adversity or childhood maltreatment lowers the threshold for emotional reactivity, making hijacks more likely (Yan, 2012; Adamec & Shallow, 2000).

Chronic stress further alters brain circuits, impairing regions like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex that normally help keep the amygdala in check (Roozendaal et al., 2009).

As a result, people with trauma histories or ongoing stress may overreact to everyday triggers, struggle with emotional regulation, and experience more frequent hijacks.

Why Amygdala Hijacks Matter

Short-term consequences

During a hijack, the amygdala overrides the frontal lobes, narrowing attention and shutting down clear thinking.

This can lead to impulsive choices such as snapping at someone, walking out of a meeting, or escalating conflict.

Once the reaction passes, many people feel guilt, embarrassment, or regret for overreacting.

Long-term effects

Repeated hijacks can damage relationships by creating cycles of mistrust or ongoing conflict.

Over time, chronic emotional overreactions place strain on mental health. As previously mentioned, heightened amygdala activity is observed in anxiety disorders, PTSD, OCD, and phobias, meaning those affected may be especially vulnerable to frequent hijacks.

This can create a feedback loop where reactivity worsens stress and reduces the brain’s capacity to regulate emotions.

When hijacks can be useful

Although often disruptive, hijacks evolved for survival. In emergencies—such as stepping out of the way of a speeding car—the amygdala’s rapid response can act before conscious thought, keeping us safe.

In modern life, however, the same reflex can misfire, turning everyday stress into disproportionate reactions.

Preventing Amygdala Hijack

In-the-moment techniques

When you feel a hijack coming on, the key is to slow things down long enough for your rational brain to re-engage:

- Name the emotion — Simply acknowledging “I’m feeling angry/upset/anxious” out loud (or in your head) helps activate the neocortex and reduce the emotional intensity.

- 6-second (or pause) rule — Pause before responding. Even counting silently to six or three while taking a breath gives your thinking brain time to catch up and breaks the automatic reaction.

- Controlled breathing — Deep, slow, diaphragmatic breathing helps calm the nervous system, slow the heart rate, and interrupt the amygdala’s momentum. Techniques like box-breathing (inhale / hold / exhale / hold) are effective.

- Change the setting / physical distance — If possible, physically stepping away or shifting perspective (e.g. move to another room, take a short walk, or simply focus on something calming in the environment) can give emotional intensity room to dissipate.

Together, these techniques help momentarily disengage from the automatic emotional response, giving your frontal cortex a chance to reassert control.

Long-term prevention

To reduce the frequency and intensity of hijacks over time, building resilience through regular habits is key:

- Mindfulness — Regular mindfulness or meditation practice helps cultivate present-moment awareness and improves emotional regulation. Over time, mindfulness can strengthen connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, making hijacks less likely.

- Stress management — Identifying personal triggers and managing ongoing stress is vital. Daily practices such as gentle exercise (walking, yoga), regular breaks, adequate sleep, and relaxation routines reduce baseline arousal, lowering the chance of being overwhelmed.

- Journaling / trigger tracking — Keeping a brief record of when hijacks occur and possible antecedent triggers helps increase self-awareness. Over time, this can help anticipate triggers, spot patterns, and plan ahead to avoid or mitigate them.

Building Emotional Intelligence

Daniel Goleman’s five emotional intelligence (EI) competencies provide a scaffold for longer-term emotional resilience and regulation: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills.

- Self-awareness: Recognising emotional cues early (e.g. physiological signs, internal tension) so you can intervene before escalation.

- Self-regulation: Practising responding thoughtfully rather than reacting impulsively. Over time, repeated use of in-the-moment techniques reinforces the ability to pause and choose.

- Motivation: Using intrinsic motivation to remain calm, intentional, and aligned with long-term goals (rather than short-term emotional reactivity).

- Empathy: Considering others’ perspectives and emotional states can help diffuse conflict and reduce emotional escalation.

- Social skills: Practising effective communication, conflict resolution, and maintaining supportive relationships can create a buffer during stressful moments. Strong interpersonal skills also mean you can repair and reflect after a hijack more constructively.

References

Adamec, R., & Shallow, T. (2000). Rodent anxiety and kindling of the central amygdala and nucleus basalis. Physiology & behavior, 70(1-2), 177-187.

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. American journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1476-1488.

Goleman D. (2005). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Howell, T. J. (2014). Daniel Goleman–Emotional Intelligence. University of Denver University College.

Hughes, K. C., & Shin, L. M. (2011). Functional neuroimaging studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 11(2), 275-285.

Kulkarni, M. (2014). Amygdala: A Beast to Tame.

Roozendaal, B., McEwen, B. S., & Chattarji, S. (2009). Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 423-433.

Yan, X. (2012). Amygdala, childhood adversity and psychiatric disorders. The Amygdala: A Discrete Multitasking Manager, 303.

Further Information

Davis, M. (1992). The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annual review of neuroscience, 15(1), 353-375.

Sah, P., Faber, E. L., Lopez de Armentia, M., & Power, J. M. J. P. R. (2003). The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiological reviews, 83(3), 803-834.