The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are the two main branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls involuntary functions like heart rate, breathing, and digestion.

The sympathetic system acts like a gas pedal, activating the fight-or-flight response in stressful situations, while the parasympathetic system acts like the brakes, promoting rest and recovery after stress.

Key Takeaways

- The sympathetic system triggers the fight-or-flight response, increasing heart rate and alertness.

- The parasympathetic system activates rest-and-digest functions, promoting relaxation and recovery.

- Both are part of the autonomic nervous system and help maintain internal balance (homeostasis).

- The vagus nerve is key to parasympathetic calming effects on the heart, lungs, and digestion.

- Stress management techniques like breathing and mindfulness support nervous system balance.

Autonomic Nervous System Overview

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is part of the peripheral nervous system and controls automatic functions like heart rate, pupil size, and gland activity.

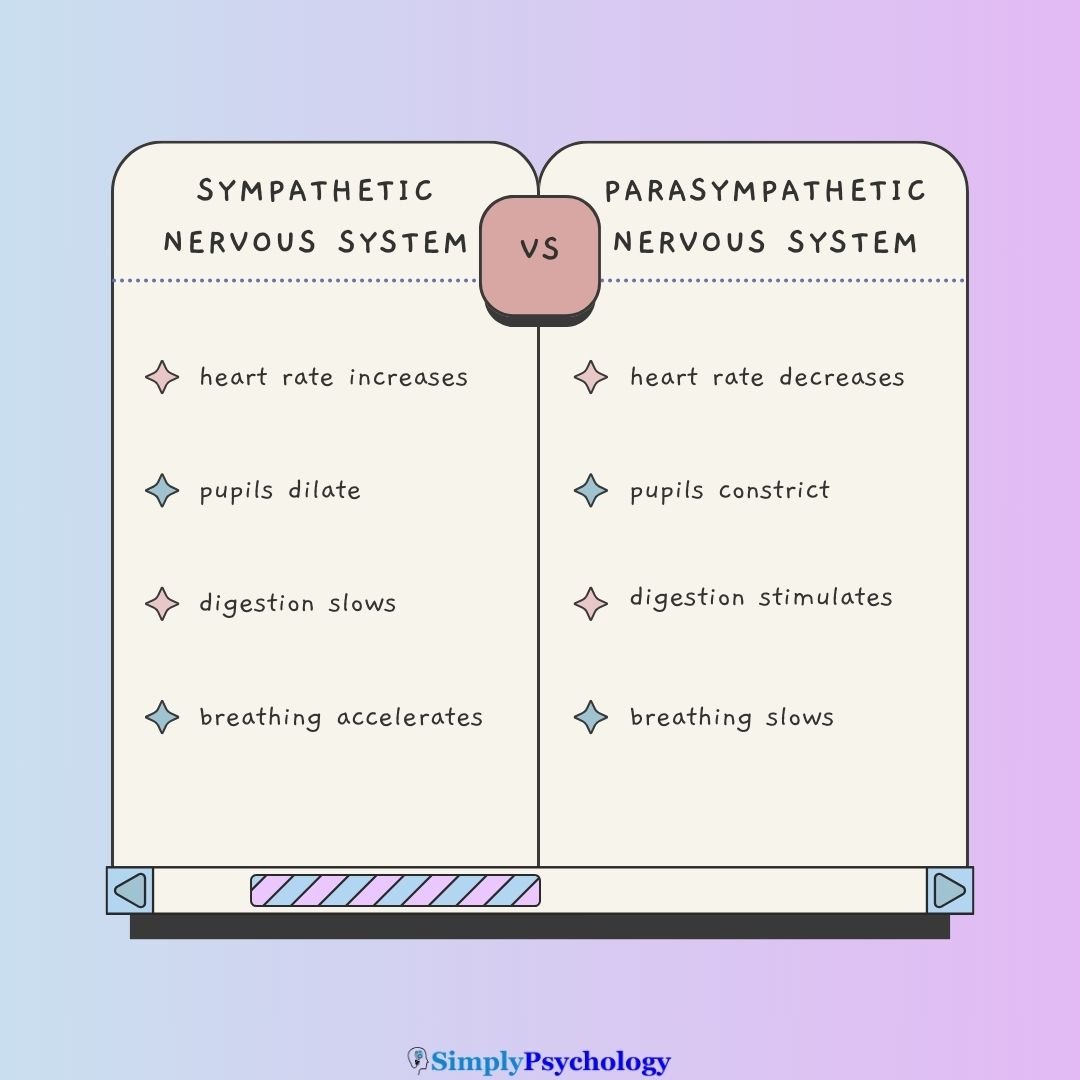

It has two main branches—sympathetic and parasympathetic—which often have opposite effects on the same organs.

Together, they maintain homeostasis, keeping the body balanced. For instance, if the sympathetic system raises your heart rate during stress, the parasympathetic system brings it back down afterward.

Key Differences Between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Systems

| Aspect | Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) “Fight-or-Flight” | Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS) “Rest-and-Digest” |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Function | Prepares body for rapid action in emergencies or stress (energy mobilization). | Calms the body and conserves energy, promoting relaxation and routine maintenance. |

| Origin (Spinal Regions) | Thoracic & lumbar spinal cord (middle of spinal cord). Preganglionic fibers are short, synapsing in ganglia near the spine. | Brainstem (cranial nerves III, VII, IX, X) and sacral spinal cord. Preganglionic fibers are long, synapsing in ganglia near target organs. |

| Neuron Pathways | Short, fast pathways – enables a quick, widespread response (signals travel quickly to multiple organs). | Longer pathways – slower, more targeted response (signals are more localized and slower to activate). |

| Heart (Cardiovascular) | Increases heart rate and force of contraction (pumps more blood to muscles). Blood pressure rises. | Decreases heart rate and contraction force (resting heartbeat). Blood pressure lowers toward normal. |

| Lungs (Respiratory) | Dilates bronchial tubes in lungs for easier airflow (breathing rate increases). | Constricts bronchial tubes (reduces airflow to resting needs). Breathing rate decreases. |

| Eyes (Pupils) | Dilates pupils (more light in for improved far vision). | Constricts pupils (protects retina; normal vision focus). |

| Muscles (Skeletal) | Tenses muscles and increases blood flow to skeletal muscles (priming body for movement). | Relaxes muscles and directs blood flow back to internal organs (restful state). |

| Digestive System | Inhibits digestion: decreases stomach movement and secretions; liver releases glucose for energy instead of digesting food. Saliva production decreases (dry mouth). | Stimulates digestion: increases stomach activity and secretions; liver stores energy (glycogen). Saliva production increases (helps digestion). |

| Urinary/Bladder | Reduces urinary output: bladder wall relaxes and sphincter contracts (you hold urine during stress). | Increases urinary output: bladder contracts and sphincter relaxes (normal urination resumes). |

| Adrenal Glands | Stimulates adrenal glands to release adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline, boosting alertness and energy. | No direct effect on adrenal medulla (no surge of adrenaline in calm states). |

| Primary Neurotransmitters | Uses adrenergic neurons (releasing norepinephrine/epinephrine). Preganglionic fibers release acetylcholine, but most postganglionic fibers release norepinephrine. | Uses cholinergic neurons (releasing acetylcholine at both pre- and postganglionic fibers). Acetylcholine promotes calming effects on organs. |

Note: Both systems are constantly active to some degree and balance each other. The sympathetic division turns up certain functions while the parasympathetic turns them down, and vice versa, depending on what the body needs at any moment.

Sympathetic Nervous System in Detail (Fight-or-Flight)

In threatening or high-pressure situations, the SNS rapidly prepares the body to face danger or flee from it.

This response evolved as a survival mechanism – it provides a burst of energy and alertness to handle emergencies.

When the sympathetic system fires, stress hormones like adrenaline (epinephrine) are released into the bloodstream, causing immediate physiological changes:

- Heart beats faster and stronger: The heart rate spikes and the heart contracts more forcefully, pushing blood to muscles and vital organs. This ensures your muscles have plenty of oxygen and nutrients to respond to the threat.

- Breathing accelerates: The bronchi in the lungs widen, allowing more air in. You start breathing quicker and deeper to increase oxygen intake. More oxygen is available for the brain and muscles, sharpening your alertness.

- Pupils dilate: Your eyes widen (pupils enlarge) to take in more light and improve vision, especially distance vision, which can help identify threats.

- Muscles tense up: Blood flow is diverted toward skeletal muscles, priming them for quick action. You might feel your muscles tighten, ready to spring into movement if needed.

- Digestion slows or pauses: Digestive processes are put on hold. Saliva production decreases (hence a dry mouth when anxious), and the stomach’s activity slows down. The body conserves energy by not digesting food during an emergency, since digestion isn’t critical for immediate survival.

- Pain perception may decrease: In the heat of the moment, the fight-or-flight response can dull pain (an adaptive benefit so that pain doesn’t debilitate you until you reach safety). This is why injuries might not be felt until after a stressful event is over (though this involves complex hormone effects beyond just the SNS).

- Energy release increases: The liver converts glycogen to glucose, raising blood sugar levels to provide quick energy fuel for muscles. At the same time, the adrenal glands dump adrenaline into your system, heightening your overall alertness and strength.

These changes happen within seconds because the sympathetic nervous system is built for speed.

Its short preganglionic neurons connect to a chain of ganglia near the spine, allowing signals to spread quickly to multiple organs.

This fast setup means you might react—heart racing—before you’re even fully aware of the threat. The SNS rapidly mobilizes the body to survive or escape danger.

Parasympathetic Nervous System in Detail (Rest-and-Digest)

The parasympathetic nervous system has the opposite role of the sympathetic system: it calms the body and supports restoration and energy conservation after stress.

Its signals come from the brainstem (via cranial nerves, especially the vagus nerve) and the sacral spinal cord, which is why it’s sometimes called the craniosacral division of the autonomic nervous system.

When active, the parasympathetic system essentially reverses the effects of the sympathetic response, guiding the body back to a balanced, restful state.

- Heart rate slows: Your heart rate decreases back toward a normal, resting rate. The force of each heartbeat also diminishes. This conserves energy and prevents wear on the heart after the stress has passed.

- Breathing becomes slower and shallow: The bronchi in the lungs constrict again, since high volumes of air are no longer needed. You begin breathing more slowly. Often, exhaling might lengthen as you relax (sometimes why taking slow deep breaths can engage the parasympathetic response).

- Pupils constrict: Your pupils shrink back to a normal size. This helps normalize vision and protect the retina now that you’re in a calmer, well-lit environment (dilated pupils let in more light than needed when safe).

- Muscles relax: Blood is redirected from the muscles to internal organs. The tension in skeletal muscles eases off, and you might feel your body unclench or even experience a sense of lightness as the adrenaline wears off.

- Digestion resumes: Saliva production increases again (mouth moistens) and digestive enzymes and stomach activity pick up to process food. You may even feel hunger or thirst once you relax, since the body is attending to digestion and hydration signals. The parasympathetic system stimulates intestinal motility and secretion, helping your body digest and absorb nutrients.

- Urination and defecation normalize: The bladder and bowel walls constrict while the sphincter muscles relax, allowing normal elimination to occur. This is why after a stressful scare, you might suddenly feel the need to use the bathroom once you’re safe – the parasympathetic system is back in charge of those functions.

- “Feed and breed” functions: In restful states, not only is digestion (feeding) promoted, but reproductive organs receive more blood flow as well, supporting sexual arousal and other reproductive processes.

While the sympathetic nervous system activates the body quickly and broadly, the parasympathetic response is slower and more targeted.

Much of this calming effect is carried out by the vagus nerve, which sends signals from the brain to organs like the heart, lungs, and digestive system to help restore balance.

How do the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems work together?

The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work like a finely tuned see-saw, constantly adjusting to keep the body in homeostasis—a stable internal balance. They rarely operate in isolation.

Instead, they function in opposition but also in coordination, with one system dialing up activity while the other dials it down depending on the situation.

For example, during a stressful event—like narrowly avoiding a car accident—the sympathetic nervous system takes over.

Your heart races, muscles tense, and breathing quickens as your body prepares for action. This is the classic fight-or-flight response, driven by adrenaline and norepinephrine.

Once the threat passes, the parasympathetic nervous system steps in to calm things down. It slows your heart rate, relaxes your muscles, and restarts digestion.

You may feel shaky or exhausted—signs your body is transitioning back to its resting state.

In a healthy body, both systems are active to some degree. The sympathetic system maintains readiness, while the parasympathetic system supports recovery.

This balance is essential.

Chronic overactivation of the sympathetic system can lead to high blood pressure, anxiety, and sleep problems.

Meanwhile, excessive parasympathetic influence can cause symptoms like dizziness or fainting in rare cases.

Together, these two systems help the body respond to challenges and recover afterward, maintaining the stability needed for everyday function.