For many autistic people, work is a mix of opportunity and challenge — a place where unique talents can shine, but also where sensory overload, unwritten rules, and the pressure to mask can make each day exhausting.

The topic matters because the employment gap for autistic adults is very large. Only about 3 in 10 working-age autistic people in the UK are in any paid work, compared with around 5 in 10 for all disabled people, and 8 in 10 for non-disabled people.

Many autistic graduates are unemployed long after finishing their studies; those who are employed tend to be underemployed, less likely to have permanent contracts, and often in roles that they are overqualified for.

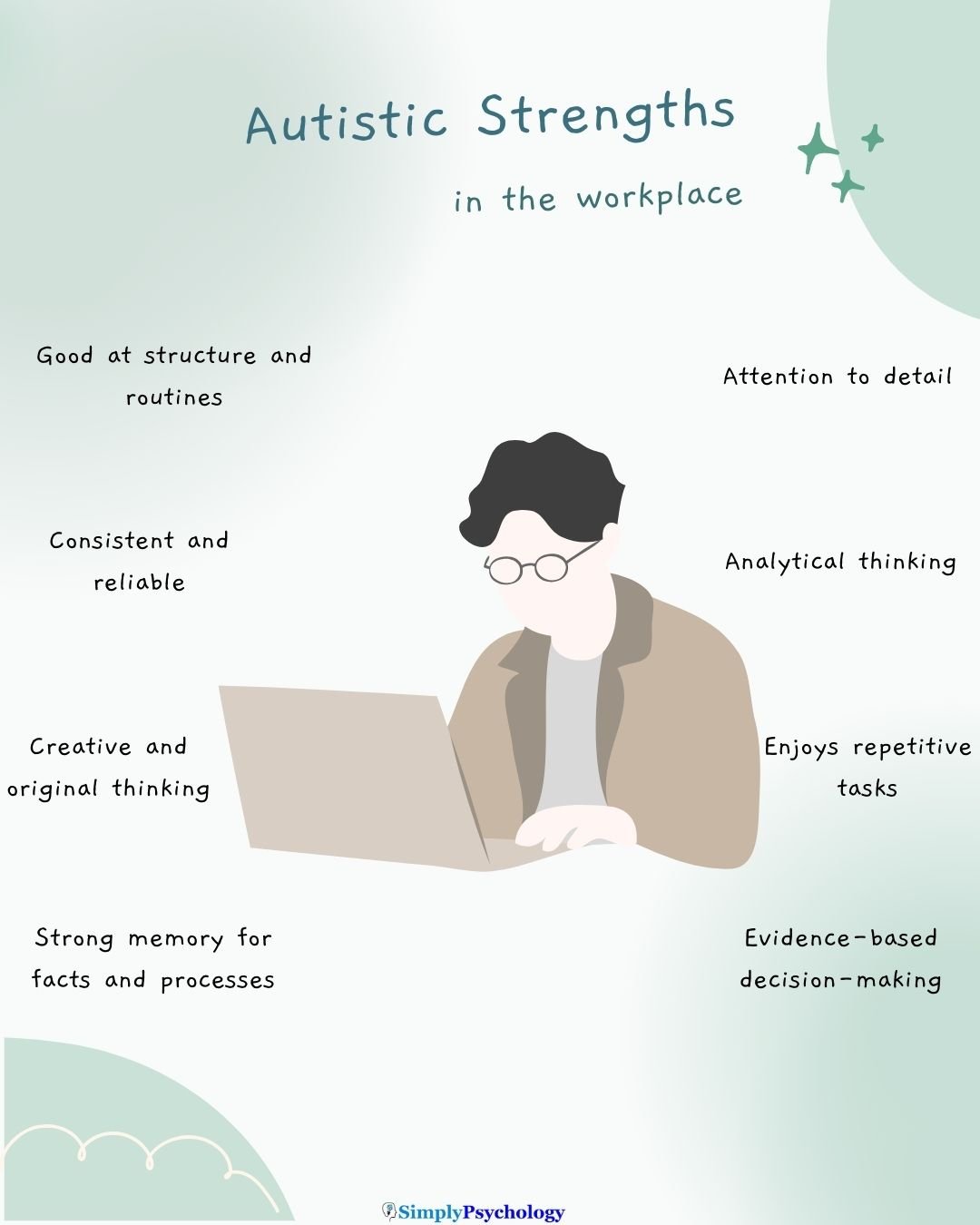

Strengths Autistic Employees Bring

Autistic people commonly report and research shows several strengths that can become real advantages in work, especially when the environment values clarity, predictability, and respects sensory/social differences.

Detail Orientation & Strong Focus

Many autistic individuals excel in tasks needing precision and long periods of sustained attention.

For example, roles like quality control, data analysis, software testing, or auditing benefit greatly from spotting anomalies, small inconsistencies, or subtle patterns others might miss.

Research finds that “attention to detail” as a common autistic strength.

Honesty & Loyalty

Autistic employees often bring transparency, integrity, and steadfastness. Many say they dislike deceit or hidden agendas and prefer fairness (likely due to justice sensitivity and black and white thinking).

In workplace forums or surveys, people report being “trustworthy, honest, and loyal” and holding themselves to high standards even under pressure.

This loyalty often shows up in low turnover once a supportive, stable job is found.

Innovative Problem-Solving & Creativity

Autistic employees often approach challenges from fresh perspectives, less bound by the social conventions that shape neurotypical thinking.

This freedom can produce creative, logical, and highly original solutions. In design or technical fields, it may mean noticing connections others miss; in workplace problem-solving, it often results in novel ways to resolve persistent issues.

Such originality not only drives innovation but also broadens team perspectives.

Memory and analytical skills

Many autistic people also demonstrate strong memory for detail — whether recalling technical information, processes, or systems. This supports consistency and accuracy across tasks.

Their analytical and structured thinking helps them break complex problems into manageable steps, leading to solutions that might not occur to others.

Rational, Bias-Free Thinking

Recent research shows autistic people often demonstrate “enhanced rationality”: less influenced by common cognitive biases, and more likely to weigh information objectively when making decisions.

In business or technical settings, this can mean clearer judgments and decisions less swayed by groupthink.

Value of Routines

Autistic employees may be exceptionally punctual and consistent in meeting deadlines. Their steady approach helps ensure accuracy and quality, and they are often willing to take on repetitive or process-driven tasks that others might find tedious.

Dedication to routine also supports thoroughness, with tasks completed carefully and without unnecessary distraction.

It’s important to emphasise that these strengths show up most strongly when the environment allows—that is, when expectations are clear, sensory load is manageable, tasks align with interests or attention style, and when there is respect for difference rather than pressure to conform.

Challenges Autistic People Face at Work

Autistic employees often face several interlinked challenges in the workplace. These are not personal failings but mismatches between needs and norms. Below are key challenges, with examples.

Difficulties with Unwritten Rules & Small Talk

Many workplace expectations are unspoken—how to join in conversations, read social cues in meetings, and know when to speak or be silent.

Some autistic people report being told “you come across as blunt” or “you don’t mingle enough” even when doing the work well.

Such misunderstandings can lead to feelings of isolation or being judged unfairly.

Sensory Overload

Overstimulation of any of the senses—bright fluorescent lighting, constant background noise, smells, fabric textures—can be overwhelming.

In many cases, this leads to physical discomfort, distraction, or exhaustion. For example, open-plan offices with bright overhead lights, multiple conversations happening at once, and wearing uncomfortable office attire can all make it hard to concentrate.

Unpredictable Demands & Changes

Unexpected shifts in schedule, last-minute deadlines, or sudden changes in task instructions can cause anxiety and stress.

When routines are disrupted without warning, many autistic people struggle to adjust quickly. Even small surprises—like a meeting location changing or a coworker showing up at an unusual time—can cascade into confusion.

The Double Empathy Problem

The “double empathy problem” is a theory that many communication breakdowns between autistic and non-autistic people are mutual—both sides misunderstand each other.

Research has shown non-autistic colleagues often misinterpret autistic behaviour, and autistic people often have a better understanding of autistic coworkers than non-autistic ones do.

These challenges tend to be more intense when the workplace is built around neurotypical norms without flexibility or awareness—open offices, inconsistent expectations, constant social interactions without breaks.

Masking and Autistic Burnout

Masking is when an autistic person consciously or unconsciously hides or suppresses autistic traits to appear more “neurotypical,” often to avoid judgement, fit in with coworkers, or keep their job.

Because workplaces tend to assume neurotypical norms in communication, social behaviour, sensory environment, and expectations, many autistic employees feel pressure to mask.

The result can be serious: ongoing exhaustion, anxiety, burnout, and even confusion about one’s authentic self.

Those with undiagnosed autism might also be masking in the workplace without realizing.

Signs You Might Be Masking at Work

- Frequently scripting what to say in meetings or conversations to avoid being misinterpreted.

- Forcing behaviour that feels unnatural: eye contact, mirroring others’ tone or gestures, suppressing natural stims, or hiding discomfort.

- Over-monitoring your behaviour: scanning for others’ reactions, adjusting everything from how you sit or talk to your appearance to avoid negative perception.

- Feeling drained, as though you are “acting” all day, followed often by mental or physical collapse once home.

Healthier Alternatives to Masking

- Use direct communication of your preferences or limits where possible (e.g. “I find sudden changes in schedule hard; could I get notices in advance?”)

- Seek or build workplace allies: coworkers or supervisors who understand autism or are open to learning, who can offer support or understanding without judgement

- Make use of accommodations or adjustments: quieter workspace, sensory breaks, flexible scheduling, written communication over verbal if that helps

- Find or cultivate peer support: mentors, fellow autistic people, or support groups who can share strategies, validate what masking feels like, and encourage authenticity

Workplace Experiences Across Sectors

There’s no single “best job” for autistic people — what matters most is how well a job’s environment fits with an individual’s needs, traits, and preferences.

Below are how some sectors often map onto common autistic strengths and challenges.

Office & Knowledge Work

- Fit factors that help: structured tasks, clear deadlines, possibility for individual or small-team work, written communication, and predictability.

- Common challenges: open-plan offices can be noisy, bright, and distracting; expectations may be vague (meetings without agendas, unwritten social norms); multitasking or switching tasks on short notice can be stressful.

- Example: Auticon (an IT consulting company employing many autistic adults) shows that roles in software testing and data analysis can be well-suited when outcomes are clearly defined and tasks are consistent.

Service & Customer-Facing Roles

- Fit factors that help: routine interactions, clear scripts or guidelines; ability to plan ahead; being in roles where honesty and commitment are appreciated.

- Common challenges: frequent unplanned social interaction; responding to changing customer demands; sensory stress from crowds, noise, or unpredictable schedules.

- Example: Some forums and inclusion programs report that in hospitality or retail, the unpredictability of customer flow and noisy, busy environments often make these roles taxing unless supports are in place (quiet back rooms, consistent schedule, ability to take breaks).

Creative & Technical Fields

- Fit factors that help: ability for deep focus, working on detailed or complex technical systems, opportunity for novel thinking, less emphasis on small-talk, and more space for autonomy.

- Common challenges: creative roles can come with deadline pressures; technical fields may demand frequent collaboration, fast changes, or feedback loops; studios or workshops may be loud or visually overstimulating.

- Example: In “The Strengths and Abilities of Autistic People In The Workplace” (Cope et al., 2022), many participants in creative jobs said their autism helped them think in original or “quirky” ways and bring novelty to design. PMC

Takeaway (“Fit Factors” Summary)

- Look for roles where structure, clarity, and predictability are valued.

- Environments that allow sensory control (quiet spaces, low visual clutter, options to retreat) can make many roles possible that otherwise feel overwhelming.

- Autistic people often thrive when their strengths—focus, detail, creativity—are leveraged, and when there’s flexibility with social demands and clear communication.

Deciding Whether to Disclose

Whether to disclose being autistic at work is a deeply personal decision. It can open doors to understanding and support, but also comes with risk.

“Some autistic people find they are better understood and get the support they need after disclosing, but others report facing stigma, being treated differently and a lack of understanding and support.”

Why Some Choose to Disclose

- Access to support or accommodations: Disclosure can allow an autistic person to ask for reasonable adjustments or changes—such as quieter workspaces, flexibility, or clearer communication.

- Reduced stress of hiding / being authentic: Not having to mask constantly or worry about misunderstandings can ease anxiety. People report that disclosure makes their work life more sustainable.

Why Some Choose Not to Disclose

- Fear of stigma or discrimination: Disclosing may lead to being judged unfairly, passed over for roles, unfair assumptions about ability, or differential treatment. For example, one person said they had been treated as if they “couldn’t be trusted” after telling their employer.

- Past negative experiences & privacy: Some have experienced negative reactions before, or simply prefer to keep their diagnoses personal. Others worry that disclosure could affect promotion, peer relationships, or lead to unintended bias.

Practical Tips for Navigating Disclosure

- Consider partial disclosure: Share what you need about how you work best rather than the diagnosis label, if that feels safer.

- Gauge workplace safety: Look for signs of acceptance, past experience of inclusion, supportive colleagues or leadership.

- Choose trusted people to talk to first (a manager, HR, or ally) rather than everyone.

- Plan what you want to say: clarify what differences affect your work, what helps you, and what you’d like changed.

Building Inclusive Workplaces

For many autistic people, a truly inclusive workplace feels like this: predictable routines, environments that respect sensory differences, and recognition of strengths rather than just “adjusting deficits.”

Being able to predict changes (to schedule, to tasks, to expectations) may reduce anxiety and make them autistic workers feel more in control.

Sensory accommodations such as adjustable lighting, having quiet zones, or being allowed to wear noise-cancelling headphones are small but deeply valued.

Autistic workers also often say that when managers or colleagues notice and acknowledge their strengths — focus, precision, loyalty — it shifts their experience from feeling tolerated to feeling valued.

Peers and managers can help in several concrete ways:

- Listening & clarity: Giving clear, consistent instructions; checking in tacitly; asking rather than assuming. UK autistic adults in a survey said they appreciated when managers clearly stated what success looked like rather than expecting them to infer.

- Adjusting communication: Using written follow-ups after meetings; creating safe feedback loops; giving space/time to process social information.

- Awareness of the double empathy problem: Recognising that communication breakdowns aren’t just “autistic people failing”; there’s mutual misunderstanding. Training programmes and inclusion-led workshops can help everyone learn this.

Small adjustments often cost little but make big differences — and more companies are setting up neurodiversity-hiring programs, employee resource groups, or autism-friendly design of workspaces.

Resources

National Autistic Society: Employment

National Autistic Society: Deciding whether to tell employers you are autistic

NHS England: Reasonable adjustments in the workplace for autistic people

The Buckland Review of Autism Employment: report and recommendations

References

Cope, R., & Remington, A. (2022). The Strengths and Abilities of Autistic People in the Workplace. Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management, 4(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0037

Davies, J., Heasman, B., Livesey, A., Walker, A., Pellicano, E., & Remington, A. (2023). Access to employment: A comparison of autistic, neurodivergent and neurotypical adults’ experiences of hiring processes in the United Kingdom. Autism, 27(6), 1746. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221145377

Rozenkrantz, L., D’Mello, A. M., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2021). Enhanced rationality in autism spectrum disorder. Trends in cognitive sciences, 25(8), 685-696.

Szechy, K. A., Turk, P. D., & O’Donnell, L. A. (2024). Autism and Employment Challenges: The Double Empathy Problem and Perceptions of an Autistic Employee in the Workplace. Autism in adulthood : challenges and management, 6(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2023.0046