Eldest daughter syndrome describes the unofficial role many firstborn girls adopt in their families: part caretaker, part role model, part overachiever. These daughters often help raise siblings, manage household tasks, and even provide emotional support to parents while still being children themselves.

While any child can be parentified, the eldest daughter experience is uniquely shaped by gender expectations.

Although not a formal clinical diagnosis, the term captures a widespread social and familial pattern.

Key Characteristics of Eldest Daughter Syndrome

Early Caregiver

Eldest daughters often assume parent-like duties: babysitting, cooking, tutoring siblings, and even supporting parents emotionally.

Many feel they “grew up too fast,” losing a carefree childhood.

One woman recalls, “Since I was 13, my after-school routine was cleaning the entire house, making dinner for everyone… My parents didn’t prioritize my education”.

This premature responsibility is a defining feature of the eldest daughter role.

People-Pleasing and Obedience

Oldest daughters are often cast as rule-followers and peacemakers. They learn not to rock the boat – after all, they’re frequently told “you’re the oldest, you should know better.”

They may suppress their own opinions or needs to avoid being “disrespectful.”

Perfectionism and Pressure to Achieve

Parents frequently use the eldest as a “trial run” in parenting. Messages like “you’re the example for your siblings” create fear of failure and drive many to perfectionism.

While striving for excellence can foster resilience, it often fuels anxiety and a sense of never being “good enough”.

Hyper-Responsibility

Eldest daughters often feel it is their duty to ensure family well-being. They become organizers, mediators, and “fixers,” sometimes serving as both the family’s internal problem-solver and its external representative.

This role can leave their own needs minimized or ignored.

Emotional Suppression

Because they focus on others, eldest daughters frequently neglect their own feelings. Many learn early that anger or sadness only creates conflict, so they become the calm, dependable one.

Praise such as “I never have to worry about you” reinforces the belief that their worth lies in not needing help.

Over time, this can lead to emotional numbness, difficulty expressing vulnerability, or feeling disconnected from one’s own needs.

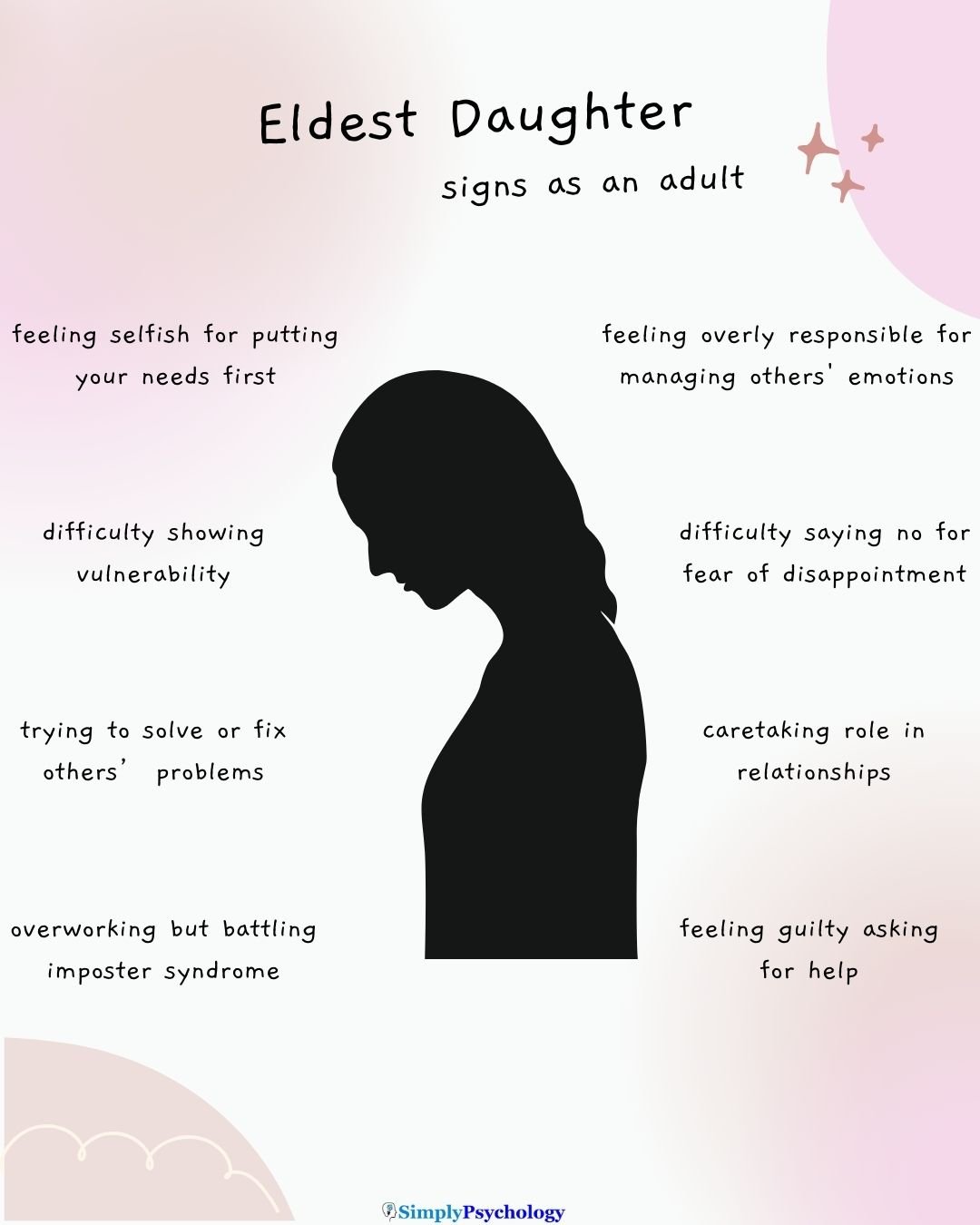

How It Shows Up in Adult Life

Eldest daughters don’t shed their roles at 18. The habits learned in childhood—caretaking, overachieving, self-silencing—often follow them into careers, relationships, and mental health.

Emotional Consequences: Anxiety, Burnout, Resentment

Constant pressure to perform fuels chronic anxiety and exhaustion. Many feel they must always be “the strong one,” leading to burnout and hidden resentment for a lost childhood.

Guilt often keeps this resentment buried, directed at themselves or their parents rather than siblings. Left unchecked, these emotions may contribute to depression or surface in midlife.

Overworking and Imposter Syndrome

At work, eldest daughters often over-function—taking on extra tasks and excelling academically. Yet perfectionism can turn into imposter syndrome: feeling inadequate despite achievements.

Many struggle to delegate or ask for help, defaulting to “fixing” rather than receiving support, which reinforces overwork and burnout.

Difficulty Setting Boundaries

People-pleasing instincts make “no” difficult. Conditioned to avoid conflict, eldest daughters overcommit at work and in friendships, often frustrated when care isn’t reciprocated.

Relationship Dynamics: Caretaking and Codependency

Romantic partners may unconsciously push them into “mom” roles. Psychologist Dr. Avigail Lev notes that eldest daughters are especially vulnerable to caretaking relationships.

They may avoid sharing struggles, creating imbalance, or gravitate toward emotionally unavailable partners because the dynamic feels familiar.

Guilt and the Burden Complex

Many feel guilty prioritizing themselves—whether moving out, pursuing education, or relaxing. In some cultures, this guilt is tied to ideals of self-sacrifice.

This “I’m being selfish” voice often echoes in eldest daughters’ minds, making it challenging to practice self-care or pursue independent goals without anxiety.

Cultural and Social Contexts: Why This Pattern Is So Common

Eldest daughter syndrome appears across cultures, shaped by gender norms, collectivist values, and economic pressures. Recognizing this context can be validating: it’s not just your family—it’s a widespread social pattern.

Collectivist Cultures and Filial Duty

In many Asian, Latin American, African, and Middle Eastern societies, children—especially daughters—are expected to contribute early.

In South Asian households, eldest girls often cook, clean, and care for siblings by primary school age.

Gender Roles and Patriarchy

Sexism shapes who shoulders family care. Daughters are raised as helpers, while brothers are excused.

Sociologist Laurie Kramer notes that even when an older brother exists, caregiving is traditionally “assigned to or assumed by” females.

In Latino families, marianismo teaches girls self-sacrifice. One eldest daughter recalled being told she must cook for a “future husband,” reinforcing that her worth lay in service.

Immigrant and Low-Income Families

Eldest daughters in immigrant households often act as cultural brokers—translating, handling paperwork, and guiding parents through systems.

If the parents speak limited English or work long hours, the oldest daughter might fill in as a parent to younger kids and an executive assistant to the adults.

Emotional Labor and the “Little Mother”

In some Asian families, the mother-daughter relationship can become one of confidant and counselor. A 22-year-old eldest daughter from a South Asian family shared,

“I’ve been conditioned to think I must mediate every argument in my family and fix them. I’m also the first person my mother turns to when she is stressed.”

A Nigerian writer described being the first daughter as “a different kind of pressure, responsibility and work,” highlighting that in many African homes the first daughter is practically an assistant parent.

Consequences of eldest daughter syndrome

A major cost of eldest daughter syndrome is identity loss. Praised primarily for dependability, many struggle to define who they are outside of caregiving.

- Role Confusion: Acting like a “little parent” often means stifling childhood needs, leading to identity struggles in adulthood.

- Living for Approval: Praise for being mature or helpful ties worth to service, making love feel conditional. As adults, many feel purposeless unless they are needed.

- Neglect of Personal Needs: Years of minimizing themselves make it hard to identify or voice their own wants. Highly attuned to others, they often remain disconnected from their own feelings.

- Mental Health Costs: Parentified children show higher rates of anxiety, depression, and sometimes complex PTSD. Many grieve lost childhoods, realizing only later how unfair the burdens were.

This identity trap makes vulnerability difficult. Wearing the “superwoman” mask can feel safer, but it’s exhausting. Healing often involves setting down that cape and learning self-worth beyond doing.

Strengths That Often Go Unseen

Amid challenges, eldest daughters develop skills that deserve recognition:

- Leadership and Resilience: Years of responsibility often translate into drive, competence, and resilience. Firstborn girls are statistically more likely to succeed academically and hold leadership positions.

- Emotional Intelligence: They become highly attuned to others’ needs, excelling in roles requiring empathy and guidance.

- Competence and Self-Sufficiency: Skilled at managing crises, many master life tasks early and inspire siblings.

- Mediator Skills: Acting as family anchors, they become skilled negotiators and organizers, valuable in work and community settings.

These strengths are often invisible to families or workplaces who rely on them. The key is learning to use these skills without self-erasure: empathy without over-giving, competence without overfunctioning.

Strategies for Renegotiating Roles

To navigate shifting roles, here are a few strategies for eldest daughters:

Communicate clearly and calmly

Family can’t read your mind. Explain what you are feeling and needing.

For example, “I’m finding it hard to manage everything; I need us to share these responsibilities,” or “I love you all, but I also need time for my own life, which means I might not be as available for every little thing.”

Use “I” statements and express love alongside firmness.

Enlist allies

If you have a reasonable sibling or a supportive other parent, talk to them one-on-one.

Sometimes a brother might step up if directly asked, or a second-born might not realize you welcome their help because you always just did it.

Allies can also be extended family members who can pitch in with caregiving duties, etc.

Set incremental boundaries

You don’t have to go from 100 to 0 overnight. You can start with small changes: maybe you won’t answer family calls during work hours, or you’ll attend Sunday dinner but not also cook the main dish every time.

Small boundary wins build confidence for bigger ones.

Expect resistance and stand firm

Change is uncomfortable. There may be guilt-trips (“you’ve changed,” “you don’t care about us”).

Remember that saying “no” to certain behaviors is saying “yes” to your well-being. Over time, your family will adjust or at least come to respect that you mean it.

Remind yourself (and perhaps others) of fairness

In dysfunctional dynamics, sometimes plainly pointing out the imbalance can help.

“It’s not fair if I’m the only one expected to do X” – this truth might prick some consciences among siblings or family.

Even if it doesn’t, you knowing it’s unfair can strengthen your resolve not to acquiesce.

How to Heal: Breaking the Cycle Without Breaking Yourself

If you recognize yourself in these patterns, you may wonder: How do I heal? Recovery doesn’t mean rejecting family or becoming irresponsible—it means creating balance where your needs matter too. Here are practical approaches to breaking the cycle.

1. Know Your Worth Beyond Service

The most important shift is realizing your value isn’t tied to what you do. Eldest daughters often internalize the belief that love must be earned through endless giving.

Challenge this by affirming: I am worthy of rest. I am enough even when I’m not helping anyone.

Think of how you love others—you value friends and siblings for who they are, not just their usefulness. Extend that same compassion to yourself.

2. Seek Therapy or Support

Professional help can untangle deep-rooted beliefs and provide new coping tools. Helpful approaches include:

- Internal Family Systems (IFS): Teaches you to connect with different “parts” of yourself, like the over-responsible caregiver or the neglected inner child, and nurture them with compassion.

- Inner Child Work: Journaling or visualization helps you acknowledge your younger self’s pain and give her permission to rest and play.

- Schema Therapy: Identifies long-standing patterns such as self-sacrifice (“I must meet others’ needs to be loved”) and mistrust (“I can’t rely on anyone”), then works to change them.

- Trauma-Informed Therapies: EMDR or somatic approaches can help process childhood trauma tied to parentification.

Support groups—online communities like r/Parentification, group therapy, or informal circles—can also reduce isolation. Sometimes the simple affirmation of me too is deeply healing.

3. Practice Boundaries—Start Small

Boundaries are like muscles; they strengthen with use.

Begin with small steps: delay responding to non-urgent texts, or tell a coworker, I’m at capacity and can’t take that on. The discomfort is normal, but each “no” builds confidence.

Boundaries aren’t rejection; they’re self-preservation. They reduce resentment and ultimately improve relationships.

If guilt arises, journal about why the boundary is healthy or talk it through with a trusted friend.

Over time, you can set bigger limits—delegating caregiving, refusing to bankroll siblings, or clarifying how you expect to be treated.

4. Reclaim Time and Joy

Rediscovering who you are outside responsibility is key.

Ask yourself: What did I enjoy before I had to grow up too soon? Whether it’s drawing, reading, or music, give yourself permission to indulge again.

Therapists sometimes assign “play” activities—coloring books, games, or simply leisure without productivity goals—to reconnect adults with joy.

Activities like journaling, meditation, or gentle exercise help you tune into your own needs.

Prompts such as What do I truly want right now? or If I didn’t feel responsible for anyone, what would I do today? can help uncover neglected desires.

5. Cultivate Self-Compassion

Many eldest daughters carry a harsh inner critic that insists they’re never doing enough. Healing requires replacing that voice with kindness.

Dr. Avigail Lev recommends practices like loving-kindness meditation. Try imagining a close friend with your struggles—what comfort would you give her? Say those words to yourself.

Writing self-compassion letters or practicing soothing rituals—tea, a blanket, gentle affirmations like It’s okay, you’ve done enough—can rewire the belief that you only deserve kindness from others.

Self-compassion also means allowing emotions without judgment. Grieve the childhood you lost. Acknowledge anger at unfair burdens. These feelings don’t make you selfish—they make you human.

6. Redefine Your Family Role

Healing doesn’t require cutting ties (though distance may be necessary in some cases). It means engaging on healthier terms.

You might still host Thanksgiving because you enjoy it—but not every family event. You might still advise siblings occasionally, but refuse to bankroll their problems or be on call 24/7.

Clear, concise communication helps: I can’t come this weekend, I need rest.

Mentally, remind yourself: you’re not your siblings’ parent, your parents’ therapist, or the family savior. Some people find it helpful to imagine handing back the “baton” of responsibility.

You can love your family while shedding duties that don’t belong to you.

7. Build an Identity Beyond “Eldest Daughter”

Ask: Who am I outside this role? You might be an artist, a leader, a traveler, or simply someone who deserves joy. Explore passions, pursue further education, or make career shifts that align with your interests.

Investing in self-development can feel selfish at first, but in reality it strengthens relationships. By living authentically, you bring your best self to others—no longer out of obligation, but out of genuine connection.