Lateralization of brain function is the view that distinct brain regions perform certain functions.

For instance, it is believed that different brain areas are responsible for controlling language, formulating memories, and making movements.

If a certain area of the brain becomes damaged, the function associated with that area will also be affected.

Understanding brain lateralization helps explain everything from how we speak to how we process emotions.

Key Takeaways

- Brain lateralization refers to the specialization of each hemisphere for certain tasks.

- Language is typically left-lateralized; spatial and emotional functions often rely on the right.

- Key discoveries include Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, split-brain research, and case studies like Phineas Gage.

- Lateralization develops with age and varies by handedness, sex, and developmental stage.

- The brain’s hemispheres always work together—even when they specialize.

What Is Brain Lateralization?

Brain lateralization refers to how certain mental processes are more dominant in one hemisphere of the brain than the other.

While both hemispheres communicate constantly through a bundle of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum, they often specialize in different tasks. This view contrasts with the holistic theory that every brain function is distributed evenly across both hemispheres.

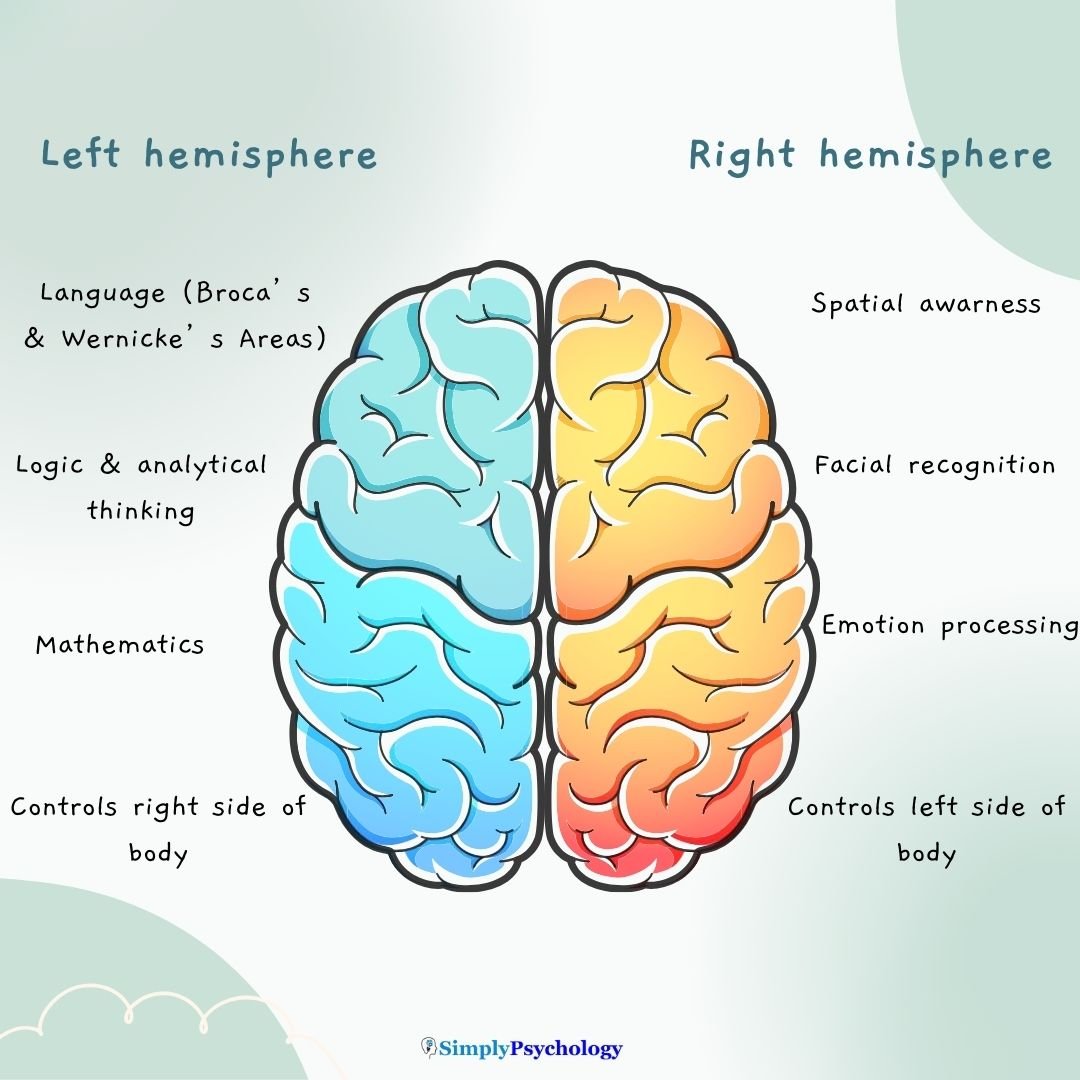

For example, the left hemisphere typically handles tasks related to language, logic, and analysis, while the right hemisphere tends to support spatial reasoning, creativity, and emotional recognition.

Left Brain vs. Right Brain

The idea of a “left-brained” or “right-brained” personality is a myth—but hemispheric specialization is real. Here’s what science tells us:

- Left Hemisphere: Processes language (including grammar and vocabulary), handles math and logic, and controls the right side of the body. It includes Broca’s area, which manages speech production, and Wernicke’s area, which supports language comprehension.

- Right Hemisphere: Specializes in spatial awareness, facial recognition, emotional processing, and controls the left side of the body. It is also more active in interpreting negative emotions and visualizing complex patterns.

Although these functions are typically lateralized, most tasks involve cooperation between both hemispheres. For example, while the left hemisphere may handle grammar, the right helps interpret tone and emotional context.

How Do We Know This? Landmark Research and Case Studies

Much of what we know about lateralization comes from early case studies and neurological research:

- Broca’s area: In 1861, French physician Paul Broca studied a patient known as “Tan,” who could only utter that single word. Upon his death, Broca discovered damage to the left frontal cortex. Broca found that other patients with similar symptoms had lesions in the same area. He concluded this region, now called Broca’s area, was essential for speech production and language comprehension.

- Wernicke’s area: In 1876, German neurologist Carl Wernicke studied patients who could speak fluently but could not understand language. He found that these individuals had damage to a region in the upper left temporal lobe. This area, now called Wernicke’s area, enables us to understand spoken and written language and select appropriate words for speech.

- Split-brain studies: Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga conducted experiments in the 1960s with patients who had undergone a severing of the corpus callosum to treat epilepsy. They found that the left hemisphere could name objects shown in the right visual field, but not those shown in the left. However, patients could draw or pick up objects seen in the left field using the left hand, revealing the right hemisphere’s strengths in spatial and motor tasks.

- Gazzaniga’s facial recognition study: In 1983, Gazzaniga found that faces shown to the left visual field (processed by the right hemisphere) were more easily recognized, supporting the idea that the right hemisphere excels in facial processing.

- Phineas Gage: After an 1848 accident destroyed part of his left frontal lobe, American railway worker Phineas Gage survived—but his personality changed dramatically. He became impulsive and unreliable, providing strong support for localization of function in the frontal cortex.

Language and Emotion Lateralization

Lateralization is especially clear in language processing. For most people (especially right-handers), language is controlled by the left hemisphere. This includes both understanding and producing speech.

However, language lateralization develops over time. A 2020 fMRI study by Olulade et al. found that children aged 4–6 showed language activation in both hemispheres.

As children aged, right hemisphere involvement decreased, and left hemisphere dominance became more apparent, suggesting that lateralization strengthens with development.

Emotion is also lateralized (Silberman & Weingartner, 1986):

- The right hemisphere plays a larger role in recognizing facial expressions and managing negative emotions.

- The left hemisphere appears more active during experiences of happiness and optimism.

In one study, patients with damage to the left frontal lobe were more likely to experience depression (Paradiso et al., 1999), while those with right frontal lobe damage often showed signs of mania or inappropriate cheerfulness (Starkstein et al., 1989).

Does Lateralization Differ Across People?

Yes—lateralization varies by handedness, sex, and age:

- Handedness: A 2002 fMRI study by Szaflarski et al. found that left-handed individuals often show more bilateral activation during language tasks, meaning they may use both hemispheres for language.

- Sex differences: A study by Tomasi and Volkow (2012) found that males had increased right-lateralized connectivity in temporal, frontal, and occipital cortices, while females showed more left-lateralized connectivity in the frontal cortex. This may relate to typical cognitive strengths—males often outperform on spatial tasks, while females excel in language-related tasks.

- Developmental differences: As shown in Olulade et al.’s (2020) study, children show more balanced hemispheric activation that gradually becomes more lateralized with age.

Additionally, a review by Reber and Tranel (2017) found that men and women differ in how they lateralize emotional and decision-making functions in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC).

For instance, male patients with right vmPFC damage showed more behavioral deficits than those with left-side damage, while the reverse pattern was not observed in female patients (Tranel et al., 2002).

Why It Matters

Understanding lateralization helps clinicians diagnose and treat brain injuries, strokes, aphasia, and emotional disorders. It also deepens our insight into how brain structure shapes cognition and behavior.

Although lateralization provides important insights, it’s essential to avoid oversimplifications. We are not simply “left-brained” or “right-brained”—we are whole-brained humans whose hemispheres work in constant collaboration.

References

Clements, A. M., Rimrodt, S. L., Abel, J. R., Blankner, J. G., Mostofsky, S. H., Pekar, J. J., Denckla, M. B. & Cutting, L. E. (2006). Sex differences in cerebral laterality of language and visuospatial processing. Brain and Language, 98 (2), 150-158.

Gazzaniga, M. S., & Smylie, C. S. (1983). Facial recognition and brain asymmetries: Clues to underlying mechanisms. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society, 13 (5), 536-540.

Olulade, O. A., Seydell-Greenwald, A., Chambers, C. E., Turkeltaub, P. E., Dromerick, A. W., Berl, M. M., Gaillard, W. D. & Newport, E. L. (2020). The neural basis of language development: Changes in lateralization over age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117 (38), 23477-23483.

Paradiso, S., Johnson, D. L., Andreasen, N. C., O’Leary, D. S., Watkins, G. L., Boles Ponto, L. L., & Hichwa, R. D. (1999). Cerebral blood flow changes associated with attribution of emotional valence to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral visual stimuli in a PET study of normal subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156 (10), 1618-1629.

Reber, J., & Tranel, D. (2017). Sex differences in the functional lateralization of emotion and decision making in the human brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95 (1-2), 270-278.

Silberman, E. K., & Weingartner, H. (1986). Hemispheric lateralization of functions related to emotion. Brain and Cognition, 5 (3), 322-353.

Sperry, R. W. (1967). Split-brain approach to learning problems. The neu.

Starkstein, S. E., Robinson, R. G., Honig, M. A., Parikh, R. M., Joselyn, J., & Price, T. R. (1989). Mood changes after right-hemisphere lesions. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 155 (1), 79-85.

Szaflarski, J. P., Binder, J. R., Possing, E. T., McKiernan, K. A., Ward, B. D., & Hammeke, T. A. (2002). Language lateralization in left-handed and ambidextrous people: fMRI data. Neurology, 59 (2), 238-244.

Tomasi, D., & Volkow, N. D. (2012). Laterality patterns of brain functional connectivity: gender effects. Cerebral Cortex, 22 (6), 1455-1462.

Tranel, D., Bechara, A., & Denburg, N. L. (2002). Asymmetric functional roles of right and left ventromedial prefrontal cortices in social conduct, decision-making, and emotional processing. Cortex, 38 (4), 589-612.

Further Reading

- Gainotti, G. (2014). Why are the right and left hemisphere conceptual representations different?. Behavioral neurology, 2014.

- Macdonald, K., Germine, L., Anderson, A., Christodoulou, J., & McGrath, L. M. (2017). Dispelling the myth: Training in education or neuroscience decreases but does not eliminate beliefs in neuromyths. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1314.

- Corballis, M. C. (2014). Left brain, right brain: facts and fantasies. PLoS Biol, 12(1), e1001767.

- Nielsen, J. A., Zielinski, B. A., Ferguson, M. A., Lainhart, J. E., & Anderson, J. S. (2013). An evaluation of the left-brain vs. right-brain hypothesis with resting state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging. PloS one, 8(8), e71275.